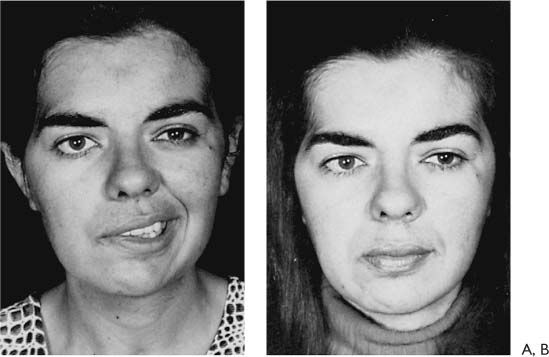

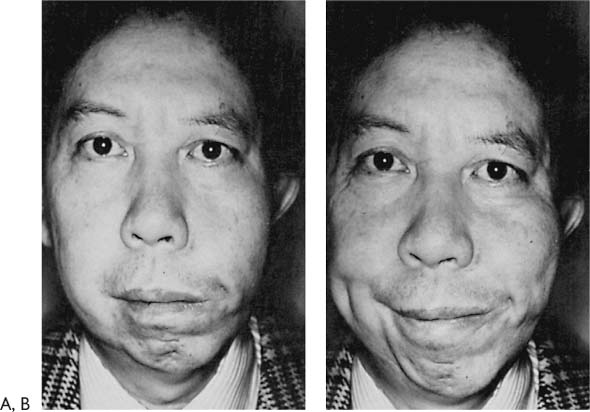

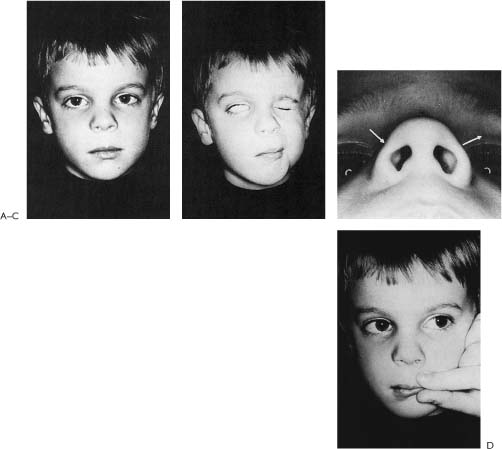

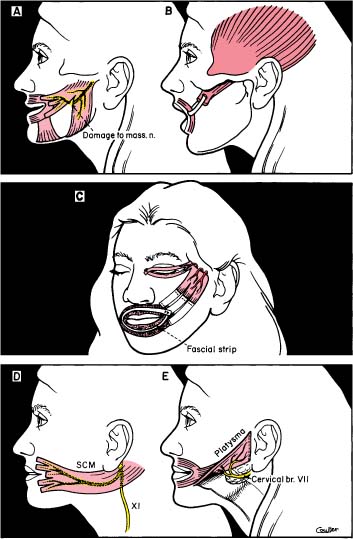

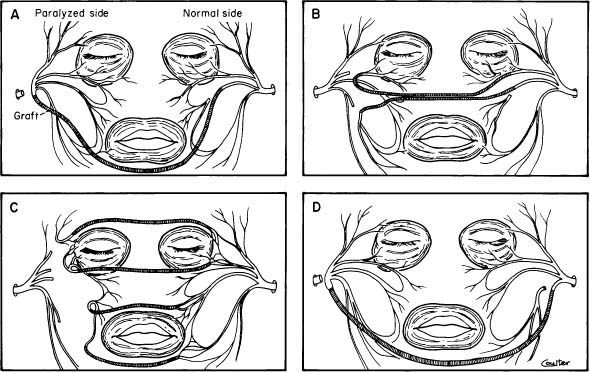

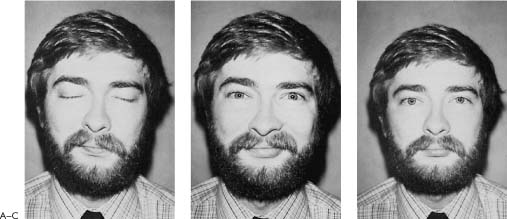

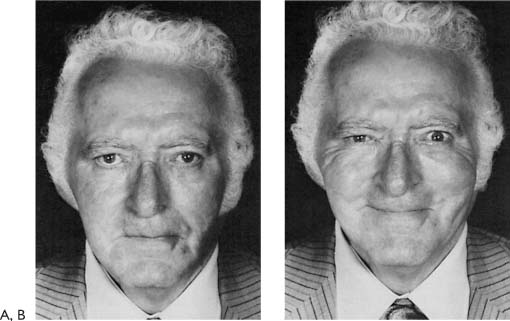

1 Nathan Bedford Forrest, an American Civil War Confederate general, was asked how to be successful in battle. He replied “Get there first with the most.” The best results achieved with facial reanimation techniques require nerve repair as soon after injury as possible or a combination of techniques that will give the strongest facial movement. The condition of facial paralysis has attracted the attention of the artist and sculptor through the ages as a stylistic grotesqueness for which there was no reprieve. In the mid-19th century, the medical profession recognized the problem as one that might be improved by muscle transposition and skin tightening. These meager steps were fraught with disappointment because of technical deficiencies and a lack of understanding regarding the neuromuscular and physiologic changes associated with facial paralysis. What followed was a period of stagnation regarding correction of the vast variety of anatomical and physiologic conditions with which congenital and acquired, immediate and longstanding, and partial and complete facial paralysis are associated. Over the past 100 years, the approach to these conditions has changed greatly as the result of advances made in otologic and general surgery during World Wars I and II. Originally management of facial palsy focused on the facial nerve itself; appreciation of the important role of the facial muscles came later as the fundamentals of facial paralysis began to come into focus. Within the past three decades, greater understanding of and more significant advances in the treatment of this condition have been achieved than in all preceding periods. Literally an avalanche of new ideas in this field has provided clinicians with hitherto unavailable basic information about the regenerative potentials of damaged nerves and muscles in the face. A host of new tests document the degree, the level, the severity, and the progress of the paresis. New and imaginative techniques for suturing, grafting, crossing, and implanting nerves, and for transferring regional muscles and implanting free muscles have greatly improved the results of facial nerve repair. Advancements in instrumentation and technology have paralleled the development of these new techniques. This renaissance also has had its confusions and its flawed experiments, but enough techniques have been developed based on sound knowledge of principles of nerve innervation and regeneration that a new era of facial nerve reanimation has been entered. The possibility that surgery could be performed on the facial nerve was conceived in 1821 when Sir Charles Bell1 established that the facial nerve was indeed the motor nerve to the muscles of the face. He described the condition of facial paralysis with such detail and clarity that the idiopathic variety still bears his name. Nerve Repair Drobnick2 performed the first nerve anastomosis in 1879 by connecting the facial nerve to the spinal accessory nerve. Manasse3 performed anastomoses with the spinal accessory, hypoglossal, and glossopharygeal nerves in 1900. Stacke4 resected a portion of the facial nerve in the fallopian canal and juxtaposed it in 1903. Ballance5 reported on anastomosis to the spinal accessory and hypoglossal nerves in 1924. Martin6 repaired the facial nerve in the fallopian canal by end-to-end suture in 1927. In 1927, Bunnell7 sutured the nerve in the fallopian canal, and in 1930, he performed the first facial nerve graft. Ballance and Duel8 both established the feasibility of facial nerve grafting in 1932. Lathrop’s,9 and Myers’10 contributions during World War II were most important in that they established the fact that this particular cranial nerve had exceptional capabilities for regrowth and that significant, and at times astounding, improvements in facial paralysis could be accomplished by simple and routine techniques. At that time, nerve grafting and nerve approximation were accomplished using 4–0 silk and under direct visualization (without magnification). There was no doubt that these humble and unpretentious efforts were effective. After World War II, Conley subsequently applied these concepts to tumor surgery in the head and neck, Maxwell introduced them into the university circles, and Miehlke carried them to Europe. Myoneurotization Myoneurotization was first advanced by Lexer and Eden11 in 1911. Erlacher12 reported on this phenomenon in 1915. Owens13 advocated the transplantation of the masseter muscle into the face to accomplish this neurotization in 1947. A review of the variety of regional muscle transposition techniques with their limitations is illustrated in Figure 1-1. In 1971, Thompson14 proposed the free transplantation of skeletal muscle under certain criteria. Hakelius15 supported Thompson’s work in 1974. Conley16 reviewed his experience with the facial nerve in parotid gland surgery in 1975. Rubin17 emphasized the criteria for and usefulness of muscle transposition in 1977, while Harii, Ohmori, and Torii18,19 used free muscle transposition with neurovascular anastomosis to rehabilitate the paralyzed face. Weiss20 and Sunderland21 wrote texts describing myoneurotization. Cross-face Graft Scaramella22 described the technique for placing a cross-face nerve graft in 1970. Anderl23,24 modified this technique and discussed some of its limitations and criteria for use (Fig.1-2). Oriented Fascicular Nerve Repair Miehlke25 and May26 both described the spatial orientation of fibers in the facial nerve in 1973, permitting Millesi27,28 in 1977 to use techniques of fascicular grafting to develop a technique of facial nerve grafting. This, in essence, was the beginning of a new era in managing facial paralysis, but its wellsprings go back over 100 years to the original pioneers, experimenters, and investigators just described. There has been a maturing of the process of rehabilitation of the paralyzed face since the publication of the first edition of this book. This maturation emphasizes the most practical surgical techniques, and adds significant scientific data to enhance treatment. Some of the more complex procedures, which had theoretical endorsement, have become less appealing. The introduction of the simpler and more effective treatments that deal primarily with eyelid closure have, in the main, superseded the Silastic encircling and temporalis muscle transposition (Fig. 1-1C)17 and free muscle transplantation14 for this purpose. The mechanics of the use of spring leverage, gold weight loading, and improved lower lid tightening are not only technically appealing, but also functionally and aesthetically effective (see Chapter 6). Figure 1-1. Historical review of regional muscle transposition with limitations of each technique. Some types of regional muscle transpositions: A, Lexer’s original technique risked transecting nerve supply to masseter muscle. B, McLaughlin procedure attaching coronoid process to circumoral fascia lata suspension. Movement is not at the lip-cheek crease. C, Original technique of temporalis transfer with fascial strips or superficial temporal fascia turned down to obtain length. This technique as depicted can cause eye closure with chewing, ectropion of lower eyelid, muscle bulk in cheek area, and trismus from circumferential perioral fascia. D, Sternocleidomastoid transposition. Movement is more unnatural, in the wrong direction, and muscle is bulky. E, Platysma transposition. Muscle is thin and delicate, and does not provide much power; pull is in the wrong direction. The brilliant concept of cross-face grafting, with its variety of variations (Fig. 1-2), delayed staged procedures and protracted morbidity, and at times unpredictable results, is now much better understood as to what it entails and can offer than when it was first presented as a potential method of choice. This has caused a significant reduction in its clinical applicability, but also has highlighted its value in certain complex cases. It became realized that it was not competitive with other techniques for a variety of reasons in the management of these problems. Figure 1-2. Variety of techniques for faciofacial cross-face graft. A, Scaramella’s cross-face graft. The graft may also be passed over the upper lip. B, Fisch’s technique. C, Anderl’s modifications. In Conley’s experience the frontal and marginal mandibular functions return in only 15% of patients, even with primary nerve grafting. D, Conley’s preferred technique is to anastomose the entire lower division of the normal side with the main trunk of the paralyzed side. Exposure is easily obtained with standard parotid incisions. The graft may be passed over the upper lip. The concept of oriented fascicular facial nerve repair was based on a false premise. It has been established that the facial nerve is not oriented as it courses through and exits the temporal bone.29 Further, oriented fascicular repair has not been demonstrated to improve results. The techniques used to rehabilitate the paralyzed face have increased in sophistication from merely suturing the nerve to techniques of nerve and muscle substitution that incorporate microvascular procedures (see Chapter 5). Each has a place in treatment. Some are quite specific, some give similar results, and many will be modified. The final degree of rehabilitation achieved may be spectacular, but because all operations incorporate elements of experimentation regardless of the indications for surgery or the surgeon’s skill, some may fail to reanimate the face, and some may even cause greater deficits. Techniques to treat facial paralysis are by no means perfect, and many problems remain to be solved. Operations such as the cross-face nerve graft and free muscle graft attest to the innovators’ genius and ambition. However, they unquestionably have limited and specific roles in rehabilitation of the paralyzed face. Thus, some operations gain temporary popularity and are performed on the basis of an enthusiastic presentation. This process appears to have become integral to the evolution of knowledge, but the need to state the criteria for use of every new operation needs to be emphasized. There is no single operation applicable to all cases of facial paralysis. A careful preoperative assessment will point the direction of management, depending on the etiology, clinical status, optimum course of treatment, and expected results. The patient quite understandably wishes to have a normal face, and the surgeon can usually restore some degree of normalcy: today it is possible to achieve some degree of improvement in every case of facial paralysis. The improvement may be in tone, in protection for the eye, or some degree of movement of the face upon intention. However, these enhancements often leave much to be desired, and the patient as well as the surgeon must appreciate that once the facial nerve is damaged, there is no chance to restore normal facial function. Even in the most successful cases where voluntary movement has been dramatically restored, there will be significant and permanent deficiency in involuntary control. This is all too evident when the patient involuntarily responds to emotion and only the normal side of the face moves. This imbalanced muscular movement with involuntary emotion is the hallmark of paralysis. The involuntary nerve pathways and mechanisms for involuntary muscle movement are unknown and thus can never be restored after injury. This does not mean that the patient cannot accommodate for deficiency; he/she can accommodate a great deal by supervening some degree of restrictive control on the normal side and some degree of intentional movement on the paralyzed side. However, the creation of human expression that is balanced, restrained, and symmetric requires effort and practice. Many of the stigmata of facial paralysis can be improved by three basic operations (see Chapters 2 through 4 for details of surgical technique). The most effective of these techniques is facial nerve repair (Figs. 1-3 and 1-4). Hypoglossal nerve crossover (Figs. 1-5 and 1-6) has been extremely effective when the proximal segment of the facial nerve is not available for grafting, and regional muscle transposition has proved to be helpful when the mimetic muscles are either nonexistent or nonfunctional or the distal facial nerve is fibrotic. It is fully appreciated that there are many variations on these three basic techniques that may be indicated and may be helpful under certain circumstances. The time between nerve injury and repair was the most significant factor in determining which procedures were appropriate and whether the surgery would be successful. The best results were achieved when the central nerve stump was connected to the peripheral system of the facial nerve performed within 30 days of injury. When the central stump was not available or the time between injury and repair was between 1 and 2 years, the procedure of choice was a hypoglossal-facial nerve crossover. When repair was performed between 2 and 4 years after injury, frequently the hypoglossal-facial nerve crossover was combined with a muscle transposition procedure (Fig. 1-7). If the distal nerve and muscle system were not suitable for the procedures just described, temporalis muscle transposition was the preferred reanimation technique. This procedure is competitive with free muscle transplantation neurovascular anastomoses (see Chapter 5). The “three basic operations” work to some extent in every case; however, results can be improved further by periodic fine tuning surgery. Facial symmetry at rest with oral competence and creation of a dynamic smile is the goal of the reanimation surgeon. Eyelid reanimation is achieved by performing separate procedures, thus allowing patients to close the eye independently from mouth movement (see Chapter 6). Figure 1-3. A-C, Excellent results in free ipsilateral facial nerve grafting following radical ablation for cancer of the parotid. Figure 1-4. A, Free autogenous cervical nerve graft to right facial nerve following adenoid cystic carcinoma of parotid 2 years previously. B, Excellent movement and simulated emotional response. Figure 1-5. A, Complete facial paralysis following gunshot wound of skull. B, Hypoglossal crossover has produced good symmetry of the face and eyebrows and a simulated smile. Figure 1-6. A, Return of function to the right side of the face by hypoglossal nerve crossover 4 to 6 months following radical resection of the parotid gland. There is good tone in repose. B, The facsimile of a smile is produced by movement of the tongue. Muscular response in all quadrants of the face is strong with the exception of the forehead. C, Although the right hypoglossal nerve was crossed over to the facial nerve, there is no atrophy or limitation of movement of the tongue in this instance. Figure 1-7. A, Facial paralysis following resection for cancer of ear canal. Masseter muscle was transposed. B, Three years postoperatively with good facial movements and regional neurotization into the orbicularis oculi. Selecting the appropriate technique for each given situation must address many questions: (1) What was the cause of the paralysis? (2) Is the paralysis complete? (3) How long has the paralysis been present? (4) How old is the patient? (5) Is the patient in good health? (6) What is the patient’s psychological status; in particular, are the patient’s expectations for rehabilitation realistic? (7) What problem does the patient feel should be addressed; is a particular aspect of facial function troublesome? (8) What are the functional defects? (9) What is the patient’s life expectancy? (10) Are any other cranial nerves involved, such as the trigeminal, vagus, or hypoglossal? (11) What surgical reanimation procedures have already been performed? When, and what were the results? (12) What is the surgeon’s role in decision making? Knowing the cause of facial paralysis may be critical in determining how best to restore function. Most facial palsies evaluated for possible rehabilitation will be the result of trauma, either surgical or accidental. If the injury was acute and the nerve was severed, the best results are achieved when repair is performed within 30 days of injury. The following situations demonstrate how the causes of facial paralysis influence treatment: It is important to determine if the facial paralysis is complete before planning reanimation surgery. Although patients may have facial paralysis of long-standing, some may have partial or complete sparing of parts of the face, while others may have experienced some spontaneous regeneration of the facial nerve. In the latter case, some synkinetic movement will be evident; for example, smiling may cause the eye on the involved side to close. Evaluation of a small degree of facial motor function may require that the examiner use his finger to break the pull of the muscle on the opposite (intact) side when trying to determine if there is any spontaneous motion on the paralyzed side; it also helps to look for nasal flaring, to evaluate eye closure by noting whether the eyelids approximate, and looking for facial movement with the patient lying down to eliminate the influence of gravity (Fig. 1-8). Clearly, if there has been partial recovery of facial nerve function or if only certain branches of the facial nerve are involved, rehabilitation efforts should be directed to the most involved region. Specific rehabilitation procedures will be discussed in Chapters 2 through 9. The results of electrical tests are useful in that they help the surgeon to determine the degree of injury. This is especially true in the acute stage, although they can help to evaluate functioning of the peripheral nerves in long-standing injuries as well. Figure 1-8. Evaluating facial function in a 5-year-old boy 3 days postonset acute Bell’s palsy, right side. A, Facial tone impaired when face examined in repose. Note widening of the interpalpebral fissure and slight sagging of the corner of the mouth on the right side. B, Attempt at eye closure and grimacing. Eyelids do not approximate. The cornea rolls up underneath the upper lid indicating good Bell’s phenomenon. No movement of the mouth. C, The nasal ala flares on the normal side but not on the involved side. D, Fixing the corner of the mouth on the normal side so that the weak side will not be pulled toward the normal side. This may uncover some minimal movement on the weak side.

Perspective in Facial Reanimation

John Conley, M.D., and Mark May, M.D.

Evolution of Facial Reanimation Techniques

Historical Review

Evaluation of Modern Concepts

Three Basic Operations for Reanimating the Face

Factors in Selecting Surgical Technique

Cause of Paralysis

Degree of Paralysis

Duration of Paralysis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree