CHAPTER 29 Peroneal Tendon Injury and Repair

MANAGEMENT OF TENDINITIS

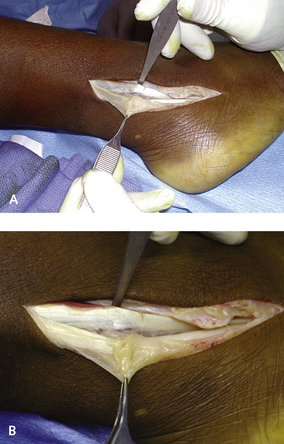

There are many causes of tendinitis or inflammatory-type symptoms related to tendon disease. If a patient presents after injury with pain behind the fibula or a fullness over the tendons associated with pain on resisted eversion, then either a tear or tenosynovitis is present. The cause may have been not a discrete injury but rather repetitive episodes leading to the presenting clinical problem. If the injury is not acute, then the likelihood is that either inflammation, constriction, or infiltration of the tendons is present. A common presentation may be that in which an area of pain behind the fibula is worsened by passive dorsiflexion of the ankle. Instead of a tear of the tendon, a low-lying muscle belly of the peroneus brevis is present, causing symptoms by virtue of the volume effect in the retinaculum (Figure 29-1). As the foot dorsiflexes, the tendons are sucked into the fibula groove, and if the muscle volume is increased, pain will develop from impingement.

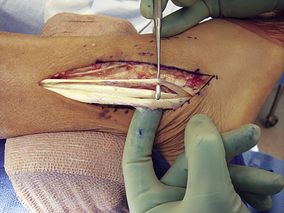

Another, less common cause of pain other than acute inflammation is chronic fatty infiltration of the tendon (Figure 29-2). A typical clinical manifestation to be aware of is chronic pain distal to the tip of the fibula along the lateral calcaneus, where the tendons may be constricted as they pass in their separate sheaths along the peroneal tubercle. Although the tubercle may enlarge for no particular reason, enlargement definitely is more common in patients with heel varus or a cavus foot deformity. The pathomechanism in such cases may be chronic friction and pressure of the tendons on the tubercle, causing hypertrophy. This constriction will cause thinning and narrowing of the tendons (Figure 29-3). The tendon changes will in turn be worsened by the increased stress on the tendons incurred when the heel is in varus. Insertional peroneus brevis tendinitis can occur but is surprisingly not very common. One unusual cause of insertional tendinitis has been identified as an unossified os vesalianum (Figure 29-4).

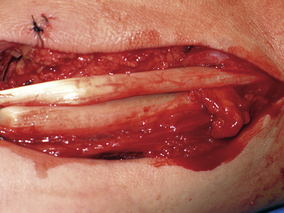

Figure 29-3 Tenosynovitis without rupture was noted in this patient following a hypesiflexion injury.

REPAIR OF ISOLATED TEARS OF THE PERONEAL LONGUS AND PERONEAL BREVIS TENDONS

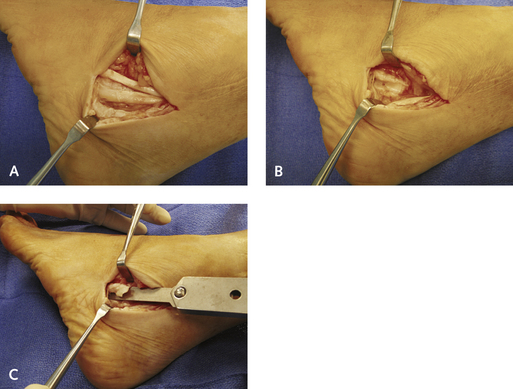

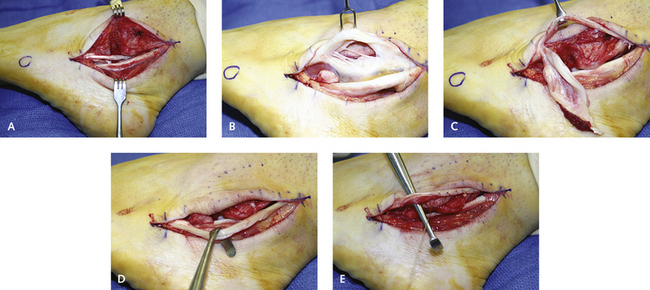

The decision has to be made whether to repair the split or to excise a portion of the tendon. Considerations in this decision include the size, length, and extent of the split. If at least 50% of the tendon can be preserved, then the split portion may be excised longitudinally. The remaining tendon can be left intact; if further splits are encountered, the tendon is “tubed” with a running absorbable suture (Figure 29-5). If ankle instability and peroneal splits are associated with heel varus, then all three components of the deformity can be addressed simultaneously using one extensile incision, through which the tendon repair, the ankle ligament reconstruction, and the peroneal repair can be performed (Figure 29-6). If the tear of the brevis tendon is extensive, reaching both proximal and distal to the fibula, a portion of the tendon may still be excised or even used as part of a nonanatomic ankle ligament reconstruction (Figure 29-7).

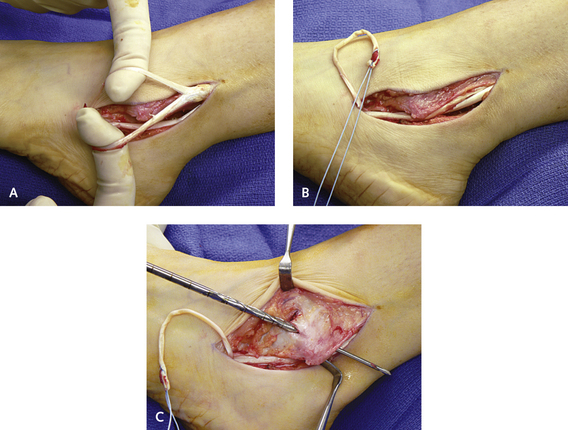

Tears of the peroneus longus generally occur distal to the fibula and are commonly constricted, split, or torn alongside the peroneal tubercle (Figure 29-8). Presence of focal pain along the lateral margin of the calcaneus in proximity to the peroneal tubercle warrants prompt exploration, because a tear of the tendon can be prevented by releasing the retinaculum and removing the peroneal tubercle. If additional procedures are not required simultaneously, the peroneal sheath can be released endoscopically without excising the tubercle, but constriction may recur. The longus and brevis tendons distal to the fibula have a separate sheath, and both tendons should be opened with small scissors. The split in the tendon is identified under the separate retinaculum, and the peroneal tubercle is debrided if it is seen to be enlarged. I use bone wax on the raw abraded surface under the peroneal tubercle once the repair is done.

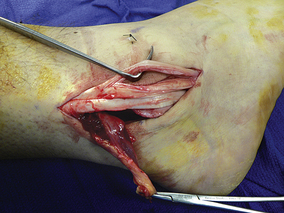

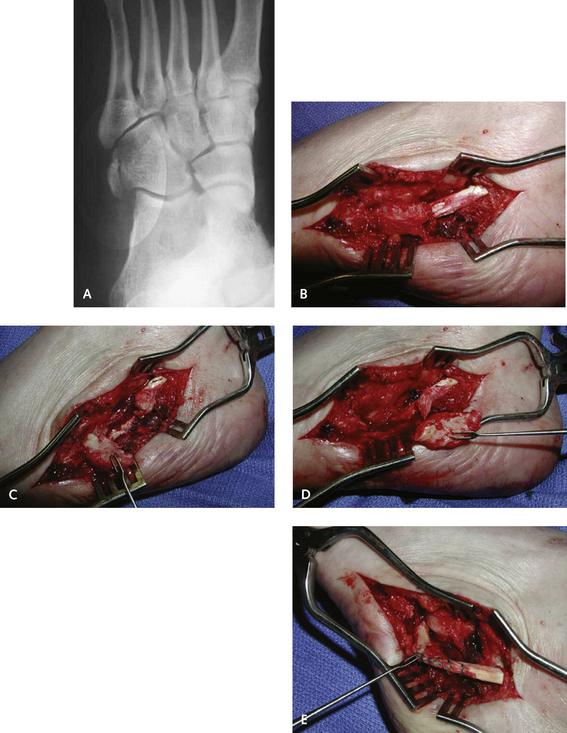

The cuboid is the more frequent location for a peroneus longus tendon tear in association with various pathologic conditions of the os peroneum as the tendon winds underneath the cuboid (Figure 29-9). Occasionally the os peroneum is visible radiographically, and its more proximal location from the undersurface of the cuboid indicates the rupture. Long-standing tears cannot be repaired in end-to-end fashion because the retracted portion of the tendon is difficult to reattach distally under the cuboid. The same limitation applies for a rupture that occurs at the junction of the os peroneum, because excision of the os peroneum frequently leaves a defect greater than 1 cm, which is difficult to repair. For a more acute injury, however, with careful excision of the os peroneum, the shell of the remaining longus tendon can be repaired by “tubing” the tendon as it passes under the cuboid (Figure 29-10). A decision has to be made, however, whether this atempt at repair is worthwhile (i.e., whether the tendon should be cut distally) and whether a tenodesis should be performed to the adjacent peroneus brevis tendon. This side-to-side tenodesis of the peroneus longus or peroneus brevis tendon is an acceptable procedure (see Figure 29-9); however, insertion of the peroneus longus into the cuboid is preferable. Although transfer of the longus to the brevis is commonly performed to realign a cavovarus foot deformity, I worry that scarring may cause symptoms distally in the normal brevis tendon. Generally, therefore, unless I specifically want to rebalance the hindfoot in a cavovarus deformity, a ruptured peroneus longus is inserted into the cuboid with an interference screw (Figure 29-11).