CHAPTER 2 Perimenstrual Skin Eruptions, Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis, Autoimmune Estrogen Dermatitis

Introduction

The activity of many skin diseases fluctuates in relation to the menstrual cycle. Some eruptions are confined to the premenstrual period and are considered as part of the premenstrual syndrome. Furthermore, many chronic dermatoses also flare premenstrually. Since the menstrual cycle is controlled by the sex hormones, premenstrual deterioration is thought to be an effect of progesterone, the predominant circulating hormone of the premenstrual period. Hypersensitivity to progesterone can be demonstrated in some of these cases, when the condition is known as autoimmune progesterone dermatitis1. However, hypersensitivity to estrogens may also occur (autoimmune estrogen dermatitis), although it is rarer than with progesterone2.

Sex hormones and the skin

Estrogens have been shown to suppress sebaceous activity but have little or no effect on the apocrine glands. They increase dermal hyaluronic acid levels with a consequent increase in the water content of the dermis and slow the breakdown of dermal collagen, possibly by increasing the conversion of soluble collagen to the insoluble form. Estrogens also stimulate epidermal melanogenesis, accounting for the transient hyperpigmentation that commonly occurs premenstrually, particularly around the eyes and nipples, and they have also been shown to slow the rate of hair growth. Estrogens alone appear to possess anti-inflammatory properties and will reduce the cutaneous response in delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

The perimenstrual dermatoses

The premenstrual syndrome

Perimenstrual eruptions fall into three categories. An eruption recurring cyclically, and confined to the premenstrual period, may be considered part of the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 The Premenstrual Syndrome

| Seborrhea, acne vulgaris |

| Edema, weight gain |

| Nausea, vomiting |

| Constipation, frequency of micturition |

| Breast fullness/tenderness |

| Headache, migraine |

| Excitability, irritability |

| Lethargy, malaise, depression |

A specific endocrine etiology for PMS has not yet been defined. Changes in endorphins, prostaglandins, and prolactin3 have all been implicated, but because of the temporal association of symptoms with the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle an abnormality of progesterone is strongly suspected3. Several hypotheses for a progesterone-related effect have been proposed, but not proven, including progesterone deficiency4, a relative imbalance of estrogen and progesterone levels, and a progesterone allergy5.

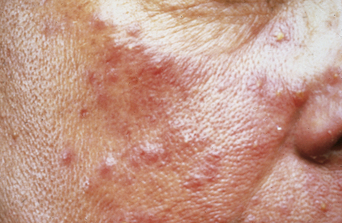

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common disorders treated by dermatologists. It is a disease of the pilosebaceous unit leading to the formation of open and closed comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. The noninflammatory lesions are open comedones (blackheads) and closed comedones (whiteheads). Papules and pustules constitute the superficial inflammatory lesions, and cysts and nodules, and occasionally deep pustules, make up the deep lesions. In most patients several types of acne lesions are present simultaneously. In mild acne, scattered comedones and/or papules with a few pustules predominate. In moderate acne more papules and pustules are present (Figure 2.1), whereas nodulocystic lesions usually predominate in severe acne.

Mild facial acne is reported by up to 70% of women during the premenstrual period, often accompanied by excessive greasiness of the scalp. Perioral dermatitis, which is common in teenage girls, is quite frequently cyclical. In addition, edema of the hands and feet, and more rarely patchy pigmentation of the skin, may occur transiently as part of PMS.

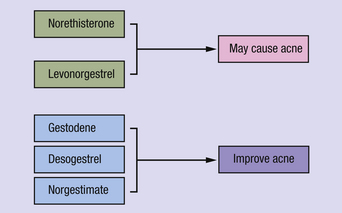

If premenstrual acne requires treatment, a topical antiseptic–keratolytic preparation (e.g., benzoyl peroxide) or antibiotic (e.g., clindamycin 1% solution) is usually helpful, but suppression of ovulation, and thus the postovulatory surge of progesterone, can also be effective. The choice of oral contraceptive pill is also important, as some synthetic progestogens (e.g., norethisterone, levonorgestrel) tend to make acne worse (Figure 2.2). For any acne-prone patient, a combined pill containing gestodene, desogestrel, or norgestimate is recommended. These progestogens appear not to have a stimulatory effect on sebaceous glands. Conversely, they raise levels of sex hormone-binding globulin, so reducing the level of free testosterone, producing a clinical antiandrogenic effect6.

Figure 2.2 Synthetic progestogens used in the combined oral contraceptive pill which may affect acne.

Although a progestogen is frequently prescribed for symptoms of PMS in which a functional deficit of natural progesterone is suspected4, it currently has no place in the management of premenstrual acne.

Premenstrual exacerbation of existing dermatoses

Many women complain of cyclical premenstrual worsening of existing dermatoses (Table 2.2). This is a common phenomenon. Inflammatory disorders, particularly of the face, become more active and irritable premenstrually, in part due to the hormonal effects of increased cutaneous vascularity, seborrhea, and dermal edema. Acne vulgaris (see Figure 2.1), rosacea (Figure 2.3), and the various forms of lupus erythematosus (Figure 2.4) are notable examples. Premenstrual flares are also well recognized in young women with psoriasis, atopic eczema (Figure 2.5), lichen planus, dermatitis herpetiformis7, pompholyx, and urticaria. Pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis may persist postpartum, classically falling into a pattern of premenstrual exacerbations8. Herpes simplex and aphthosis, although frequently recurrent, are often not strictly cyclical.

Table 2.2 Chronic Dermatoses that may Flare Premenstrually

| Acne vulgaris |

| Acne rosacea |

| Lupus erythematosus |

| Psoriasis |

| Atopic eczema |

| Lichen planus |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis |

| Pompholyx |

| Urticaria |

| Erythema multiforme |

| Pruritus vulvae |

| Pemphigoid gestationis |

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (AIPD) is a rare condition characterized by recurrent premenstrual exacerbations of a dermatosis in which sensitivity to progesterone can be demonstrated1.

History

The first case report of a cyclical eruption in which an allergy to endogenous sex hormones was suggested was by Géber9, who in 1921 reported a case of menstrual urticaria in which the eruption could be reproduced by autoinjection of premenstrual serum. The concept of sex hormone sensitization was extended in 1945 when Zondek and Bromberg10 described several patients with conditions related to menstruation and the menopause, including cases of cyclical urticaria. They demonstrated positive delayed hypersensitivity reactions to intradermal progesterone in affected patients but not in healthy controls, evidence of passive cutaneous transfer of skin reagins, and clinical suppression by desensitization.

In 1951, Guy et al.11 reported a patient with premenstrual urticaria who reacted strongly to intradermal injections of extracts of corpus luteum and was later successfully treated by desensitization. The term “autoimmune progesterone dermatitis” was eventually introduced in 1964 by Shelley et al.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree