CHAPTER 5 Pemphigoid (Herpes) Gestationis

Etiology

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is a rare autoimmune bullous disease that occurs during pregnancy and the puerperium, being associated occasionally with trophoblastic tumors, hydatidiform mole, and choriocarcinoma1. Historically it has been known by many names, with Milton first applying the term “herpes gestationis” in 1872 (Table 5.1). Clinically and immunopathologically, PG is closely related to the pemphigoid group of bullous disorders and therefore the term “pemphigoid gestationis” is preferable to “herpes gestationis,” which may otherwise encourage confusion with virus-mediated disease. Despite a clinical resemblance to herpetic lesions, viral studies of PG have been consistently negative.

Table 5.1 Historical Terminology of Pemphigoid Gestationis

| Term | Original Citation |

|---|---|

| Pemphigus gravidarum | von Martius, 1829 |

| Pemphigus pruriginosus | Chausit, 1852 |

| Herpes circinatus bullosus | Wilson, 1867 |

| Pemphigus hystericus | Hebra, 1868 |

| Herpes gestationis | Milton, 1872 |

| Dermatitis multiformis gestationis | Allen, 1889 |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Holmes and Black, 1982 |

Clinical features

PG is estimated to complicate 1 in 40 000–60 000 pregnancies1. The disease has no racial predisposition, although there is evidence that the incidence may vary according to the incidence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR3 and DR4 in different populations2.

Onset of disease

PG may develop at any time from 9 weeks’ gestation to 1 week postpartum, but usually presents during the second and third trimesters. Approximately 18% present in the first trimester, 34% in the second trimester, and a further 34% in the third trimester3. Initial presentation postpartum may be “explosive” and occurs in approximately 14% of women, but onset more than 3 days postpartum makes PG unlikely as the diagnosis3. The disease is likely to recur, usually with an earlier onset and more florid expression. When PG develops during the middle trimester there is often a period of relative remission in the last few weeks of pregnancy, but this is frequently followed by abrupt relapse postpartum1,3,4.

Occasionally, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected. Such “skip pregnancies” have an incidence of approximately 8% but remain unpredictable on a prospective basis using available data3. What is clear, however, is that recurrence is not universal. Previous reports have suggested that such pregnancies may be more likely following a change in partner or when the mother and fetus are fully compatible at the HLA-D locus, but this is certainly not always the case1,5.

Rash of pemphigoid gestationis

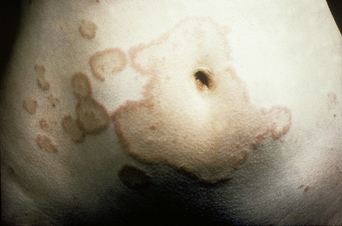

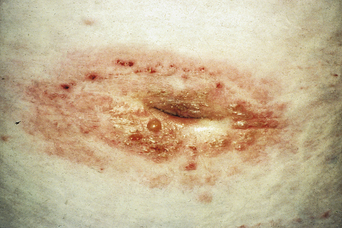

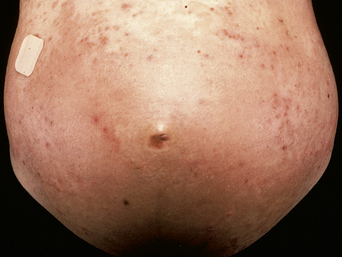

The disease typically presents with pruritic, erythematous, urticated papules and plaques which may become target-like, develop into annular wheals, or become polycyclic. Progression to clustered vesicobullous lesions on erythematous skin usually occurs within days to weeks of the initial onset of pruritus. Bullae may appear de novo on otherwise clinically uninvolved skin. Blisters are usually tense and contain serous fluid; however, pustules may be seen, albeit rarely. In 90% of patients the eruption is initially confined to the periumbilical area (Figures 5.1–5.3) with later spread to the abdomen (Figures 5.4–5.6), thighs (Figure 5.7), palms, and soles (Figure 5.8)3. The condition often becomes widespread but the face (Figure 5.9) and oral mucosa are usually spared. The blisters tend to resolve first, with the plaques of erythema persisting longer. In the absence of secondary infection, resolution usually occurs without scarring.

Figure 5.5 Pemphigoid gestationis. Pruritic urticarial lesions are spreading to involve the breasts.

Figure 5.6 Pemphigoid gestationis. The same patient as in Figure 5.5. Small bullae are developing within the areas of urticated erythema.

Natural history

Occasionally there is spontaneous clearing of the disease during the latter part of pregnancy, only to flare at the time of delivery. Postpartum flares of disease are seen in 50–75% of patients, typically beginning within 24–48 hours of delivery. The duration of postpartum flares is variable but usually ranges from weeks to several months of involvement. Some patients have been reported with disease activity for as long as 11–12 years6.

The duration of continued disease activity beyond delivery is variable and there is no correlation between disease activity and serum antibody titers. As the disease begins to resolve, recurrences associated with the menstrual cycle are common. Some women (20–50%) develop recurrences if treated with oral contraceptives (estrogens or progestogens).

Hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma

PG is rarely associated with trophoblastic tumors such as hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma1, which are most commonly produced by a diploid contribution of paternal chromosomes and have neither fetal tissue nor amnion7. Interestingly, there are no reports of PG-like disease in men with choriocarcinoma. This malignancy is relatively common and biochemically similar to normal pregnancy. Cytogenetic studies have demonstrated that the chromosomes in choriocarcinoma in men are also entirely of paternal origin7. It would, therefore, appear that placental tissue is required for the initial development of disease, not simply the presence of germinal tissue or the actual presence of fetus.

Fetal and neonatal disease

Some 5–10% of infants born to mothers with PG have cutaneous lesions1. Transient urticarial or vesicular lesions are most common and resolve spontaneously within around 3 weeks, presumably as transferred maternal antibodies are catabolized (Figure 5.10). Long-term sequelae of disease have not been reported in children born to affected mothers, nor has an increased frequency of other autoimmune diseases.

There has been controversy about whether or not PG is associated with an increase in fetal morbidity or mortality rate. In 1969 Kolodny remarked that there was no evidence of an increased incidence of stillbirth or spontaneous abortion associated with PG8. Lawley et al.9 reviewed 41 cases of immunologically confirmed PG and, by contrast, reported increased fetal morbidity and mortality rates. This review, however, relied extensively on published cases. A study of 50 pregnancies affected by PG demonstrated a slight increase in the frequency of infants that were small for dates and, because such infants have increased mortality and morbidity rates, these authors concluded that the fetal prognosis in PG was impaired10. A more recent large study found no evidence of an increased rate of spontaneous abortion or significant mortality but did demonstrate an increased incidence of both prematurity and small-for-dates babies with PG11. These observations would be consistent with low-grade placental dysfunction.

Associated autoimmune diseases

A few patients with PG have been reported to have additional autoimmune diseases (e.g., alopecia areata and Crohn’s disease) but this is unusual. However, a recent study of 87 patients with PG reported that 13.8% also had Graves disease3 (Figure 5.11). Graves disease is known to be associated with DR3, with a 0.4% female prevalence. This study also documented a slight increase in other autoantibodies in patients with PG, including antithyroid antibodies and platelet antibodies. In addition there is a 25% incidence of autoimmune diseases in the relatives of those with PG, particularly Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and pernicious anemia12.

Pathology

Immunopathology

The most characteristic finding in PG is linear deposition of C3, with or without IgG, along the BMZ of perilesional skin. Direct IF demonstrates C3 in the BMZ of clinically uninvolved skin in all patients with PG (Figure 5.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree