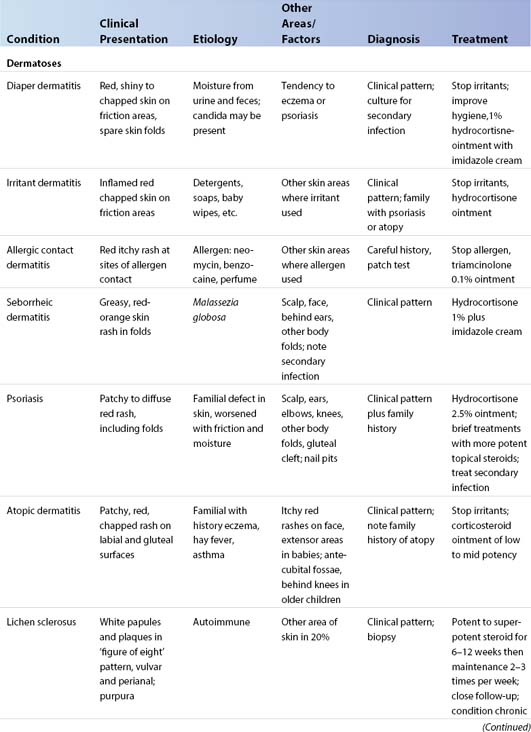

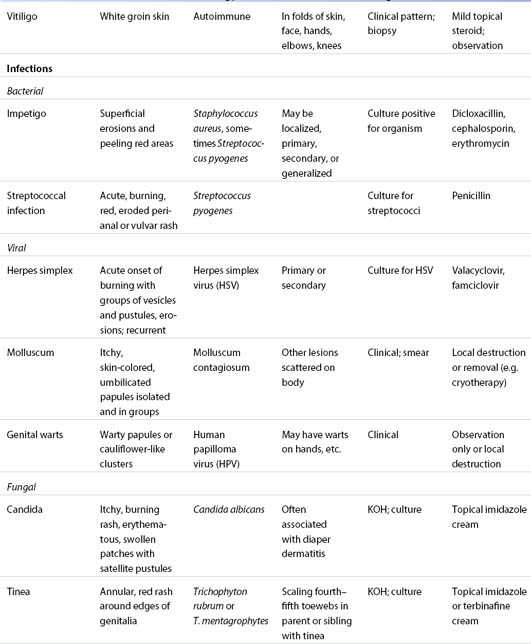

CHAPTER 26 Pediatric Vulvar Disorders

Introduction

Vulvar conditions in children include a wide spectrum from congenital malformations through infections, dermatoses, and tumors. Nondermatologic disorders are quite familiar to specialized gynecologists and pediatricians, and a full discussion of these conditions is beyond the scope of this text. Many of the conditions discussed in this chapter also occur in adults and generally the major discussion of these disorders will occur elsewhere in this book. To reduce unnecessary overlap, only capsule discussions will be found here.

Congenital vulvar abnormalities

Female genital tract developmental abnormalities are rare. They may involve only the external genitalia or the whole reproductive tract (Tables 26.1 and 26.2).

Table 26.1 Ambiguous External Genitalia

| Clinical Presentation | Diagnosis | Etiology |

|---|---|---|

| Clitoromegaly or variable phallus formation with ventral opening; variable labial formation with opening or scrotal sac formation | Female pseudohermaphroditism Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | Enzyme deficiencies (recessive) 21-Hydroxylase deficiency 11-Hydroxylase deficiency (rare) |

| Exogenous hormones | Maternal androgen-producing tumor | |

| Exogenous androgen exposure | ||

| Male pseudohermaphroditism | Lack of gonadotropin | |

| Enzyme defect in testosterone synthesis | ||

| Target tissue androgen receptor defect |

Table 26.2 Abnormalities of External Genitalia

| Disorder | Clinical Presentation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Labial hypertrophy | Long labia minora | Surgery |

| Hymenal abnormalities | Variable hymenal openings or complete closure | Surgery |

| Hemangiomas | Red to purple vascular macules, nodules or plaques with or without erosions or ulcers | Reassurance; laser destruction if extensive or ulcerated |

| Congenital nevi | Small to large pigmented macules or plaques | Biopsy if atypical; close observation as indicated |

Ambiguous external genitalia

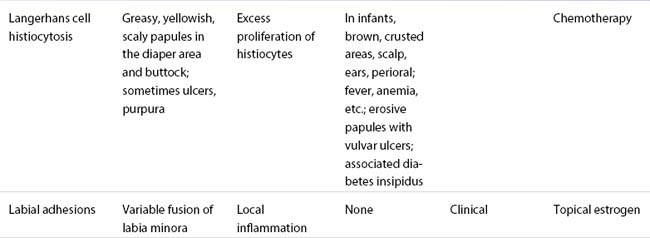

Male pseudohermaphroditism is far less common and represents only 15% of cases of ambiguous genitalia. In these infants there is a partial or complete block in the masculinization process during development due to a lack of gonadotropins, an enzyme defect in testosterone biosynthesis, or a defect in the androgen-dependent target tissue response (e.g., androgen receptor defect or 5α-reductase deficiency). Clinically these children present with varying degrees of phallus formation, scrotal sac formation, and with varying genital openings (Figures 26.1 and 26.2)1–3.

(Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

(Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Figure 26.2B Ambiguous genitalia in an XY child with partial androgen insensitivity.

(Courtesy of Dr. G. D. Oliver, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.) (Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Congenital labial hypertrophy

This relatively common developmental abnormality is typically noted at puberty. Labial hypertrophy is defined as a maximum distance of 4 cm from the base of the labium minus to the edge. Rarely it may develop as a result of lymph stasis or chronic physical pulling of the labia. Patients complain of difficulties with hygiene or local irritation with physical activity and sexual intercourse. The problem may be unilateral or bilateral (Figure 26.3). Treatment is surgical reduction.

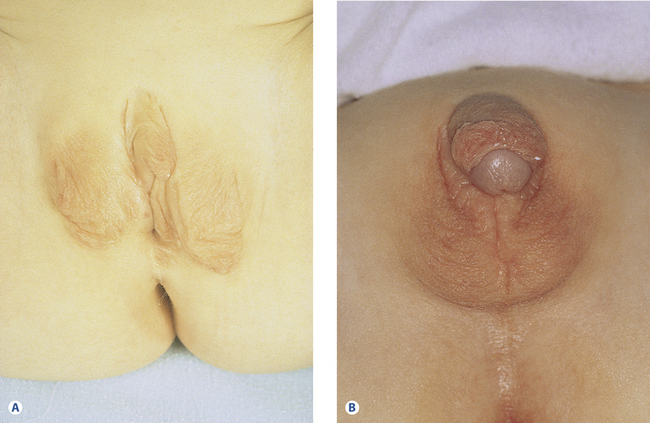

Labial adhesions

Superficial fusion of the labia minora occurs in 1–3% of prepubertal girls. It starts posteriorly and usually involves the posterior two-thirds of the labia minora. Only rarely is there almost complete labial agglutination .This is an acquired condition seen mostly in children 2–3 years of age4. The cause is unknown, but local irritation, poor hygiene, genital trauma, and lack of estrogen may all play a role5. The result is inflammation and adherence of skin surfaces on either side of the labia, giving the vulva a flat appearance. Localized posterior fusion is often minor and asymptomatic. Although this condition resolves spontaneously with pubertal estrogenization, extensive fusion leaving only a pinhole opening can result in urine retention, urinary infection, genital irritation, and burning. The first line of therapy is topical estrogen cream, used two or three times a day with gentle traction for 2–3 weeks if needed6. If extensive, surgery may be required1,7–10.

Hymenal abnormalities

The thin membrane of connective tissue over the entrance of the vagina normally has a round or crescentic opening. There can be several microperforations, giving a cribriform or fenestrated hymen or no opening at all (imperforate hymen). With only partial opening of the hymen at the time of menarche, secretions can be trapped, resulting in infection. An imperforate hymen presents as primary amenorrhea and there will be lower abdominal discomfort with progressive cyclical lower abdominal pain (Figures 26.4 and 26.5). Treatment is surgical4,11,12.

Figure 26.4 Septate hymen.

(Courtesy of Dr. G. D. Oliver, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.) (Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Figure 26.5A Imperforate hymen in a 13-year-old adolescent who presented with an acute abdomen.

(Courtesy of Dr. G. D. Oliver, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.) (Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Figure 26.5B The patient’s imperforate hymen is incised and the old blood is released.

(Courtesy of Dr. G. D. Oliver, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.) (Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Hemangiomas

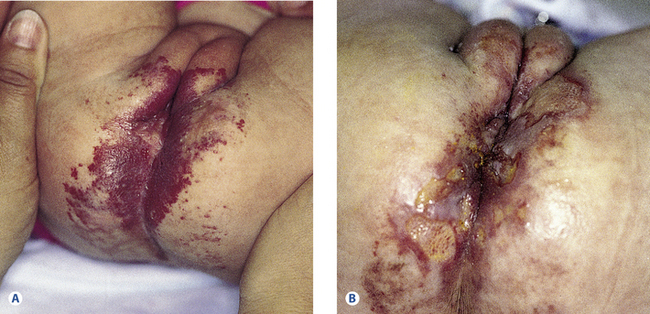

Hemangiomata are the most common vascular lesions, affecting 5% of newborns with a predominance in females (a male-to-female ratio of 1:3). These benign tumors are characterized by endothelial cell hyperproliferation and they form pink to reddish papules or plaques anywhere on the body. They usually start within a few days of birth with a flat red patch that gradually enlarges. The proliferative phase of rapid growth lasts about 8–9 months, then the lesion stabilizes for a time. Involution starts at about 2 years of age, and most of these lesions flatten into a whitish scar by the age of 9 years. Symptoms depend on size: large tumors can create considerable discomfort with ulcers, erosions, and bleeding (Figures 26.6 and 26.7). Treatment depends on the degree of involvement, and asymptomatic lesions may be left to resolve on their own. Corticosteroids may be used for problematic hemangiomata, intralesionally for small lesions and systemically for large ones. Hemangiomata that bleed or ulcerate may respond well to early laser treatment. For severe cases, co-management with a pediatric dermatologist is recommended13–18.

Figure 26.6A Rapidly growing capillary hemangioma on the perineum in a 1-month-old baby.

(Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Figure 26.6B Capillary hemangioma. Eroded ulcerated perineum 10 days after the second pulsed-dye laser treatment. The first pulsed-dye treatment was at 1 month of age, the second at 2 months of age. After laser treatment, the ulcers resolved in 3 weeks. The interval between Figures 26.6 A and B was 6 weeks.

(Reproduced from B. K. Fisher and L. J. Margesson (eds) Genital Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St Louis, 1998.)

Melanocytic nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (“moles”) are not common on the vulvar area. These melanocytic hamartomata may present at birth, when they can show varying degrees of pigmentation. Flat tan-colored macules or papules with varying degrees of pigmentation often grow and darken as the patient ages. Giant nevi present at birth (Figure 26.8) are more likely to undergo malignant transformation. Most nevi have little risk of malignant change, although rare cases of vulvar malignant melanoma have been reported in prepubertal girls. There are 13 documented cases in patients less than 16 years old. Five of these cases were associated with lichen sclerosus19–21. Treatment is observation with biopsy of suspicious lesions.

Vulvar dermatoses

Many childhood vulvar problems are associated with estrogen depletion (Table 26.3). Estrogen is an important factor in vulvar skin reactions to irritants and infection. Estrogen is present and effective during the first 3 months of life and then again 2–3 years before menarche. In the interval, the vulva is relatively estrogen-deficient. In this state, the labia minora and the vulvar epithelia are thin with a visible capillary network. The result is a weakened barrier function and the tissue is more susceptible to irritants but resistant to Candida. The estrogenized vulva is resilient and pink with plump labia minora and well-moisturized vulvar introital epithelium. This results in resistance to chemical and physical irritants but increased susceptibility to Candida.

Contact dermatitis

Irritation is the commonest cause of vulvar contact dermatitis, particularly in atopic patients. Diapers, poor hygiene habits, overzealous cleansing with caustic soaps or “wipes,” irritating creams – all can cause trouble22.

Diaper dermatitis

This term means any dermatitis in the diaper area, usually due to repeated contact irritation from urine, feces, and friction. This is the commonest skin condition in infancy, with a prevalence of 7–35%. Babies aged 7–12 months are most commonly affected. The skin is pink to red, with shiny or chapped areas of friction. Typically the convex surfaces of the mons pubis, the labia majora, and the buttocks are irritated, but the skin folds are usually spared (Figure 26.9). Children with atopic dermatitis or a tendency to psoriasis are more susceptible. With time, a mixed pattern develops due to secondary infection with bacteria and Candida. The skin in the folds and on the convex surfaces may become red, chapped, and raw with scattered satellite pustules or desquamating papules and, if severe, open ulcers may develop. Treatment is to remove the irritants and change the diapers more frequently and, when possible, to leave the infant without a diaper. Superabsorbent disposable diapers are best to reduce irritation. Routine cleansing should be with bare or vinyl-gloved hands in plain water with a soapless cleanser (Cetaphil, unscented Dove bar or superfatted soap) followed by a thorough rinse, then 1% hydrocortisone ointment. An imidazole cream (clotrimazole) is added for secondary yeast. For diaper changes away from home, cleansing with plain water or light mineral oil on a soft tissue or cotton ball is permitted23–29. “Baby wipes” are best avoided.

Irritant dermatitis

Repeated exposure to caustic or physically irritating products, usually soap, cleanser, or “wipe,” may result in erythema, itching, and burning of the labia and perineum. Children who have this problem often have a background history of atopic dermatitis, making their skin more sensitive and more easily irritated. Most vulvar contact dermatitis in children is due to irritants. Poor genital hygiene habits (especially fecal smearing of the vulva), excess exposure to soaps, shampoos, and wet bathing suits can all irritate. A thorough history is important to pinpoint the important factors. The irritants must be identified, stopped, and a topical hydrocortisone ointment prescribed.

Allergic contact dermatitis

This is not an uncommon problem in children. It occurs in up to 20% of cases of dermatitis but is seldom seen on the vulva. Typically, allergic contact dermatitis increases with age and it should be sought in any child with any persistent eczematous lesions. The commonest allergens are nickel, neomycin, thimerosal, fragrance, or wool alcohols. There may be an acute blistering eruption or a more chronic picture with erythema and scaling. Other sites may be involved if the allergen has been applied elsewhere. Patch testing may confirm the diagnosis. The condition improves over 2–3 weeks after the allergen is stopped. For severe reactions, a topical corticosteroid ointment such as triamcinolone 0.1% might be needed. If there is blistering, systemic prednisone could be used starting at 1 mg/kg daily for 4–5 days, then decreasing over 10 days30–34.

Seborrheic dermatitis

This condition produces erythema and greasy, yellowish scaling around the vulva and the labiocrural fold. In the first 3 months of life, it is often associated with a greasy dandruff-type rash in the scalp, around the ears, down the central part of the face, and in the axillae. The irritation is due to the immune reaction to Malassezia, a species of lipophilic yeast that thrives in areas rich in sebaceous glands that have been activated before birth by maternal or placental hormones. Treatment is with gentle soapless cleansing and topical imidazole, such as clotrimazole cream with 1% hydrocortisone added35,36.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common, hereditary, red, scaly rash of the skin. In infants, it may present as a chronic, sometimes itchy, diaper dermatitis with bright red, sharply outlined plaques around the mons pubis and labia majora through the perineum and often up into the gluteal cleft with varying degrees of fissuring. In young infants it often presents as a diaper dermatitis that is resistant to therapy. The white scales typical of psoriasis are not present in body folds, but may occur on elbows, knees, or scalp. A history of psoriasis in other family members helps to make a diagnosis37–39.

Treatment involves avoiding trauma such as irritating soaps and lotions, and keeping the area cool and dry. Cleanse with a bland product such as Cetaphil cleanser, unscented Dove bar, or superfatted soap. A low-potency steroid ointment (hydrocortisone 2.5%, desonide 0.05%) may be used twice a day initially, tapering to 1% hydrocortisone ointment with response. In more severe cases, mid- or even high-potency topical corticosteroids may be necessary for 1–2 weeks followed by long-term management with intermittent use of low-dose hydrocortisone. For concurrent secondary infection antiyeast topical clotrimazole and antibacterial mupirocin ointment may be needed. The topical calcineurin inhibitors can be useful as steroid-sparing agents: pimecrolimus 1% cream for milder psoriasis and tacrolimus 0.03% and 0.1% ointment for more severe. These can be used twice a day intermittently for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (see below)40–42.

Atopic dermatitis

This eruption consists of a dry itchy rash that occurs in patients who usually have a personal or family history of one or more atopic conditions: asthma, allergic rhinitis (“hayfever”), or eczema. Infants with atopic dermatitis present with chapped red skin over the cheeks and extensor surfaces of the extremities. Older children show involvement of the antecubital fossae and behind the knees. Although the typical rash is not common on the vulva, children with a background history of atopic dermatitis have much more easily irritated skin and may present with an irritant dermatitis or diaper dermatitis. Management combines avoidance of harsh, irritating soaps and cleansers; treatment of any secondary infection; and the application of a mild corticosteroid ointment, as for diaper dermatitis or a topical calcineurin inhibitor, pimecrolimus cream or tacrolimus ointment, as a steroid sparer as for psoriasis43,44. These can be used safely short-term and intermittently in children over 2 years old. Long-term safety has not been established and is controversial45–47.