Introduction

Initially developed for surgical repair of deficiencies, such as congenital pectoral aplasia, pectoral implants can be used to improve the appearance of patients with an undeveloped or disproportionate chest. Over the past decade, there has been increased interest in sculpting the ideal male form, as exemplified by provocative ads of men showing off defined abdomens and muscular pectoral regions. An adequate chest wall is psychologically very important for males, denoting fitness, strength, and power. Men are becoming a larger part of the pool of cosmetic surgery patients as noted in studies by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery [

1,

2]. For all of these reasons above, pectoral augmentation has become more prevalent among men seeking cosmetic surgery as they continue to further define their physique. Men want to be able to show their chests proudly rather than covering when confronted with events that reveal the upper torso, such as physical activity (i.e., sports) or simply relaxing at the beach. Using preformed silicone pectoral prostheses, the aesthetic surgeon is able not only to correct volume deficits but provide reliable augmentation of the pectoral region, giving men a more defined and muscular appearance.

Body Dissatisfaction in Males

Although discussed in greater depth in the previous chapters, it stands to emphasize that many men have some element of body dysmorphic disorder and wish to have a more muscular and “built” physique in order to be better accepted in society and by the opposite sex [

3–

8]. Society has created an idealistic model of the male that is oftentimes hard to attain with simple diet and exercise alone. For this reason, muscle augmentation surgery gives a male the opportunity to achieve this ideal. While augmentations for biceps and triceps are still in their infancy [

9–

11], pectoral augmentation has long been present as a means of enhancing the male physique. A man with a well-developed chest is seen as being fit, strong, and powerful [

12]. The advent of pectoral implants gave a male with an underdeveloped chest something of an option to enhance his chest and allow him to strut proudly like a peacock.

History of the Procedure

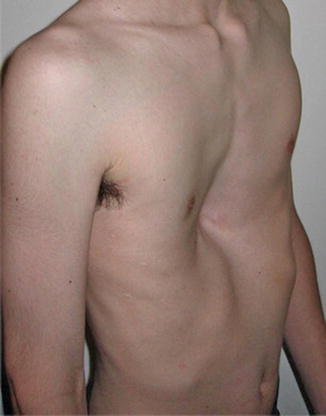

Since the 1970s, reconstructive surgeons have used solid silicone prostheses to reconstruct chest wall defects as a result of Poland’s syndrome [13]. In 1988, Sorenson [14] described his use of silicone prostheses in a subcutaneous plane to correct deformity left as a result of pectus excavatum (Fig. 5.1).

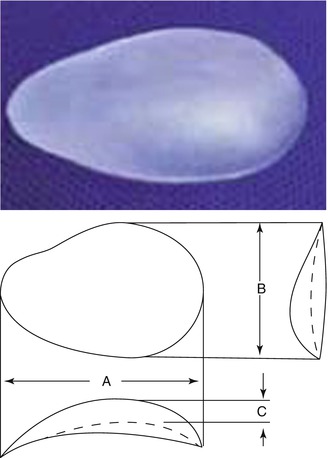

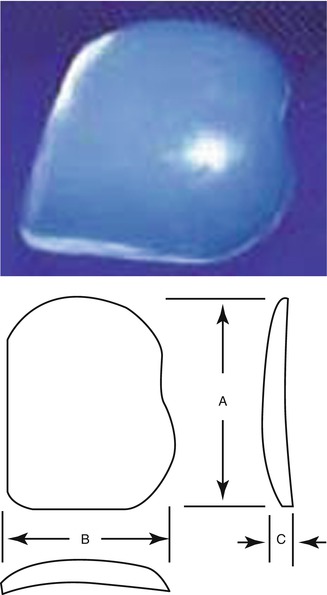

In 1991, Aiache [15] introduced his technique for aesthetic augmentation of the chest with cohesive silicone gel implants that have an anatomic design. The Aiache pectoral implant augments the sternal and costal lower two-thirds of the chest (Fig. 5.2) [15, 16]. In the same year, Novack released his extensive discussion on alloplastic implants for men, describing his work with various augmentation procedures using silicone elastomer implants (Fig. 5.3) [17]. The implants that bear his name are a more square-shaped implant that provides a more “blocky” result with less lateral fullness and increased posteroanterior projection.

Hodgkinson, in 1997 [

16], reviewed his experience of 15 years using silicone implants to correct a wide range of chest wall deformities, including muscular insufficiency, Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, and pectoralis muscle tears. His work demonstrates the true versatility of the implant in being able to correct multiple deformities of the chest. Hodgkinson further elaborates on the use of pectoral implants to correct deformities left by pectoralis muscle tears, rarely discussed in prior publications on pectoral implants. He notes that patients on occasion presented years after injuries from high-impact sports, motorcycle racing, weight lifting, and body building [

16]. Although orthopedic surgeons will sometimes reattach the pectoralis tendon back to the humerus, oftentimes the injury goes untreated in the early phase and causes patients to present once there is an obvious deformity that is more prominent in the flexed position [

18–

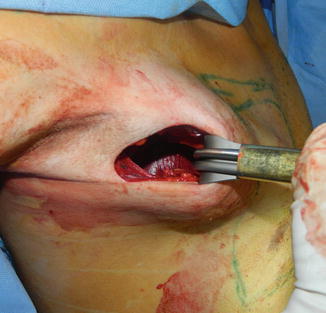

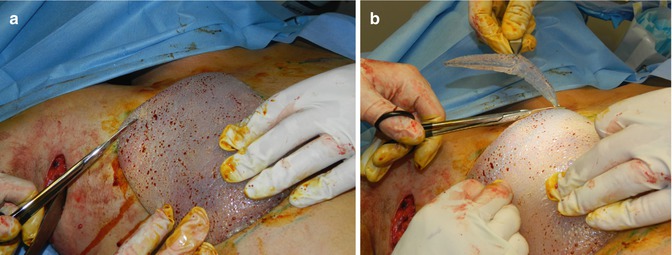

20]. Hodgkinson recommends a possible resection of the bulging protuberant muscle and suture repair of the groove produced with contraction of the pectoralis. When this is impossible, a custom silicone prosthesis can be used to camouflage the abnormality. Aside from treating defects, Hodgkinson goes on to discuss his work in pectoral augmentation surgery for treatment of muscle insufficiency. Through a 5–6 cm incision in the axilla, he describes his technique of placement of a silicone implant below the pectoralis major muscle.

In 1999, the primary author (NVC) published his work on pectoral augmentation in 16 patients for purely aesthetic purposes [

21]. Describing his experience with 16 patients served as one of the largest early evaluations of pectoral augmentation along with its risks and benefits.

In 2002, Horn [

22] further added to the literature on pectoral augmentation. In 12 patients, he performed pectoral augmentation with implants made of a cohesive silicone gel. His implant was created to more closely mirror the pectoral muscle, being rectangular in shape and having an axillary extension. In addition to ten cases of straightforward augmentation, Horn describes two patients who underwent pectoral augmentation after having undergone liposuction of the chest for treatment of gynecomastia and ended up dissatisfied by sagging skin in the chest. This was one of the first cases to describe volumizing an empty chest, making pectoral augmentation an option for treatment of loose and hanging skin in men that have lost significant amounts of weight in the chest region.

Ruiz introduced the use of buttock implants for male chest enhancement in 2003 [

23] and 2008 [

24]. Using the same technique as previously described by Aiache, he placed buttock implants into the subpectoral space, achieving good to excellent results with significant patient satisfaction.

Indications

Initially, pectoral augmentation was introduced as a means to treating asymmetries in the pectoral region left due to congenital anomalies (e.g., Poland’s syndrome and pectus excavatum) and in those patients who suffered volume deficits secondary to trauma or post-oncologic surgery. Pectoral augmentation, for purely aesthetic reasons, is indicated for the patient who has hypoplasia in the area of the chest muscle and is unable to achieve the desired projection despite vigorous exercise or muscle building. The last group of patients that may benefit from pectoral augmentation are those that have suffered some injury to the pectoral region, leaving them with an asymmetry and defect in the anterior chest.

Contraindications

While not every male presenting for pectoral augmentation suffers from muscle dysmorphia/body dysmorphic disorder, the surgeon must be aware of this and take it into consideration when considering a patient for muscle augmentation surgery. A patient who seems unrealistic in the goals of his surgery should be turned away.

Limitations

In any case of pectoral augmentation, realistic expectations should be had by the prospective patient. A patient who has preexisting asymmetry has to understand that despite augmentation there will likely be a persistent asymmetry (i.e., nipple position or volume). Patients who are severely hypoplastic or have some congenital defect may require more than one procedure with larger custom implants at a second setting to achieve dramatic augmentation as an overly aggressive augmentation in one setting may put the patient at risk of compartment syndrome.

Relevant Anatomy

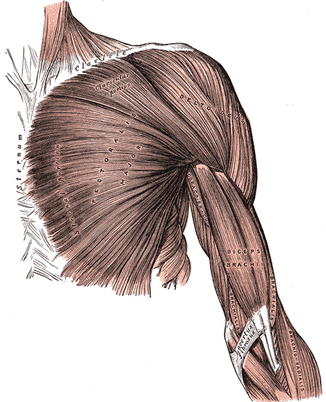

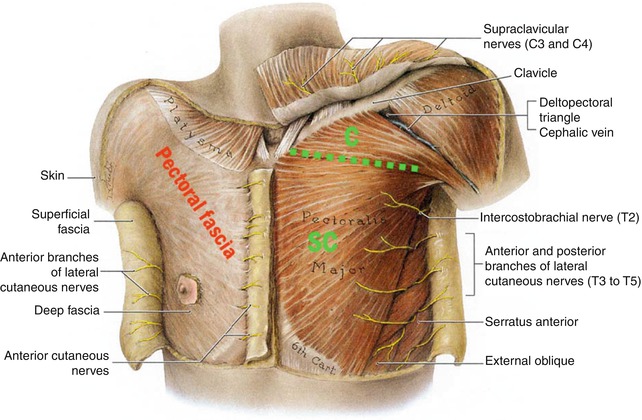

The pectoralis major is a thick, fan-shaped muscle that makes up the large part of the volume of the anterior thorax and is responsible for adducting and drawing the arm forward across the front of the chest (Fig. 5.4) [25]. It arises from the anterior surface of the sternal half of the clavicle, from the sternum, from the cartilages of all the true ribs with the exception of the first or seventh or both, and from the external oblique muscle of the abdomen. All of these muscle fibers join in a flat tendon that is about 5 cm broad and inserts into the greater tubercle of the humerus. The pectoralis is covered by a very thin pectoral fascia that is continuous with the rectus abdominis fascia below and extends cranially to the clavicles and laterally to the axilla (Fig. 5.5). The pectoralis minor sits below the pectoralis major and is a triangular-shaped muscle that depresses the point of the shoulder, drawing the scapula downward and medially toward the thorax. It arises from the upper margins and outer surfaces of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs and from the aponeuroses covering the intercostal muscles. These fibers pass upward and converge to form a tendon that inserts into the coracoid process of the scapula.

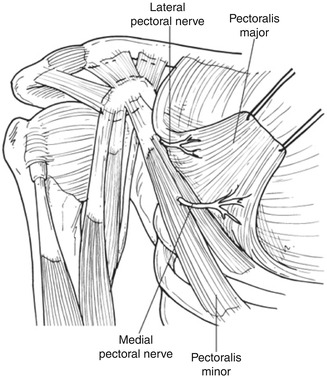

The pectoralis major muscle is supplied by the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. More recent studies have questioned the validity of this classification saying that there are in fact three pectoral nerves noted as follows: medial (inferior branch) and lateral (superior and middle branches) (Fig. 5.6) [26].

Medial Pectoral Nerve

The medial pectoral nerve (inferior branch) can be severed during access to the subpectoral plane [

26,

27]. This results in a slight loss of the pectoralis major muscle strength. In 62 % of patients, the medial pectoral nerve (inferior branch) courses through the pectoralis minor to innervate the lower two-thirds of the pectoralis major muscle. In the other 38 %, it exits around the lateral aspect of the pectoralis minor muscle. The inferior branch of the pectoral nerve is closely associated with the lateral thoracic vessels, and care must be taken to avoid not only damage to the nerve but these vessels. Dissection with fingers and blunt instruments lessens the risk of injury to these structures.

Lateral Pectoral Nerve

The lateral branch of the pectoral nerve (superior and medial branches) is also at risk of injury with submuscular implant placement as it travels on the deep surface of the pectoralis major muscle alongside the thoracoacromial artery and vein. It provides innervation to the upper one-third of the pectoralis major muscle. When injured, it produces an atrophy of the sternal aspect of the pectoralis major. Again, dissection with blunt technique helps to avoid injury to these neurovascular structures. The superior branch is relatively protected from injury due to its straight path to the clavicular portion of pectoralis major [

26].

Damage to a single branch of the pectoral nerve is typically undetectable; however, injury to both the inferior and middle branches can produce significant morbidity, namely, pectoralis atrophy, fibrosis, and limitation of shoulder movement. Hoffman, in his discussion of the anatomy of the pectoral nerves, notes in patients that have undergone modified radical mastectomy that there is a possibility of injury not only to the medial pectoral nerve but also to the lateral pectoral nerve, when dissecting in the axilla [

27]. Although frank transection of the lateral pectoral nerve is rare, aggressive electrocoagulation of the branches of the thoracoacromial artery and vein can cause adjacent nerve injury. For this reason, minimal dissection is advised in the axilla, primarily using blunt dissection, in the path of dissection to the lateral border of pectoralis major so as to minimize neurovascular injury.

Consultation/Implant Selection

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history on the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the torso and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus or patients with previous injuries. Also, patients with histories of nerve entrapment disorders should be asked about the current state of those nerves and any long-term sequelae. Preoperative goals are assessed at this point. A patient who has unrealistic expectations and is unable to comply with the strict postoperative instructions is deemed a poor candidate for augmentation. To best assess the patient’s expectations, we ask the patient to supply a picture of a body builder or person who demonstrates their “ideal” chest. The surgeon is now able to assess whether or not the patient’s goals are realistic. Patients who have congenital anomalies, a significant size disparity between the two sides of the chest, or bilateral hypoplasia, are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. Patients are also asked about their current level of activity and muscle building history, taking care to inform the patient of the need to take at least 1 month of time to recover before resuming any vigorous arm building regimens.

After completion of the history, the chest is evaluated. First, symmetry of the two sides is assessed, and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although the majority of patients present with a preexisting asymmetry of the chest, not many patients note the difference and this can be a source of medicolegal matters in the future. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. Any fatty deposits or evidence of skin laxity are noted and demonstrated to the patient. To evaluate the muscle, the patient’s pectoral region is evaluated in standing natural position as well as in flexed position. The pectoralis is evaluated at its clavicular, sternal, and costal attachments, and any asymmetries should be noted at this time. Next an evaluation of the skeleton is important. This consists of assessing the symmetry of the shoulders and rib cage and evaluating the position of the sternum. The physician should evaluate the patient from the posterior aspect and evaluate the scapula and the spine itself, taking note of any asymmetries and any evidence of scoliosis as this may affect the ability to bring symmetry to the anterior thorax. The sternum is evaluated and note is made of pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum.

At this point several measurements are taken to determine the best implant for the patient. First, the width of the muscle from sternum to anterior axillary line is assessed at the lower pole of the pectoralis. This measurement is analogous to assessing the base width for patients undergoing breast augmentation surgery. Next, the height of the pectoralis muscle is assessed by measure from the clavicle to the lower border of the muscle in the midclavicular line.

Patients who suffer from Poland syndrome should have the normal side measured so as best to approximate the dimensions on the contralateral side. Custom implants can be made for patients desiring a certain look or in those that have significant chest wall abnormality. A moulage kit can be used to construct a cast which is then sent to the implant manufacturer to create the desired implant.

Available Implants (Tables 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, and 5.4)

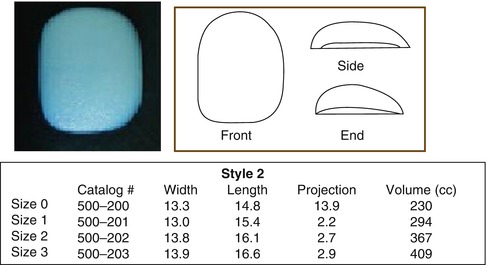

The authors’ preference is the style two square-shaped implant.

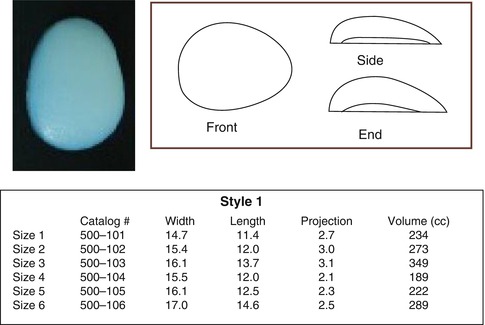

Table 5.1

Style 1 pectoral implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

Table 5.2

Style 2 pectoral implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

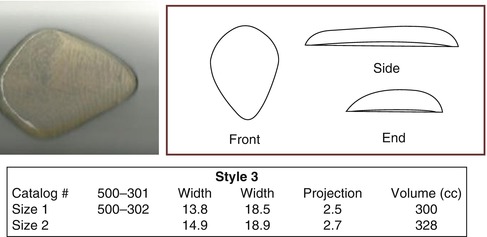

Table 5.3

Style 3 pectoral implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

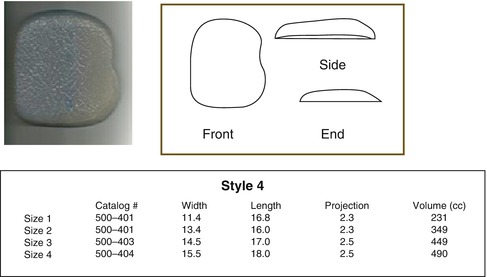

Table 5.4

Style 4 pectoral implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

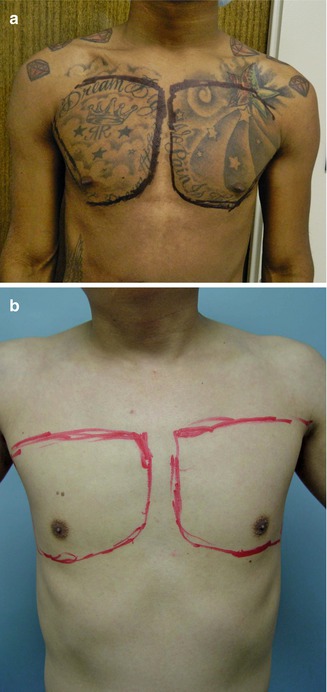

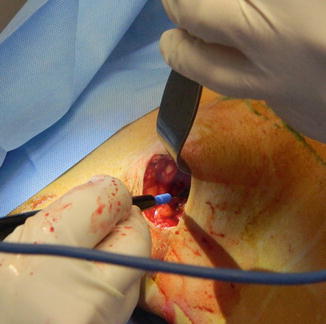

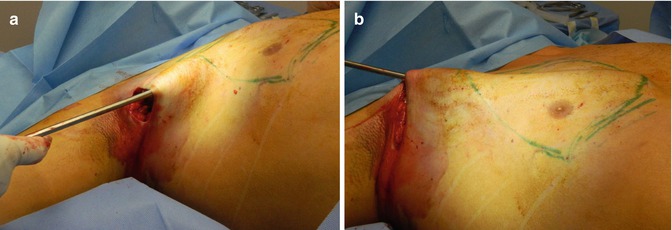

Preoperative Planning and Marking

With the patient in the standing position, preoperative markings can be made so as best to hide the incision. The patient’s arm is abducted and then raised over the head to clearly define the lateral sweep of the pectoralis major. The patient’s natural inframammary fold is also marked. The patient is then repeatedly asked to flex the pectoralis, and the borders are marked squarely on the chest to mark the proposed outline of the muscle and hence the implant position. This will help to direct dissection intraoperatively (Fig. 5.7). A 5–6 cm incision is marked in the hair bearing area of the axilla. Midline may also be marked from the level of the sternal notch down to the umbilicus (optional).