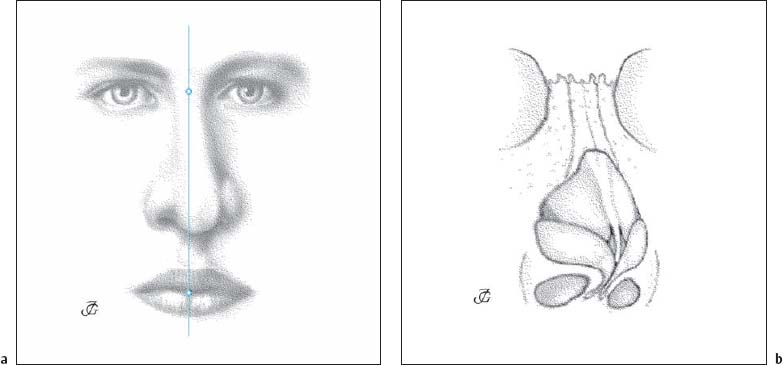

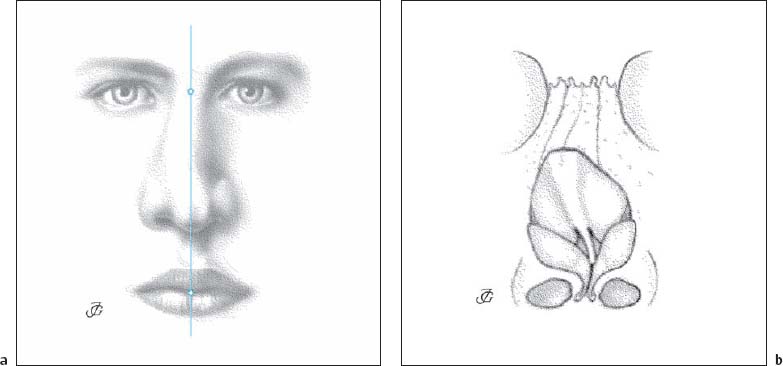

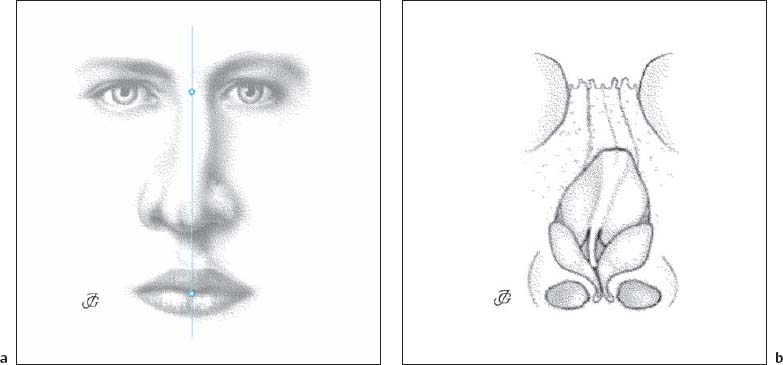

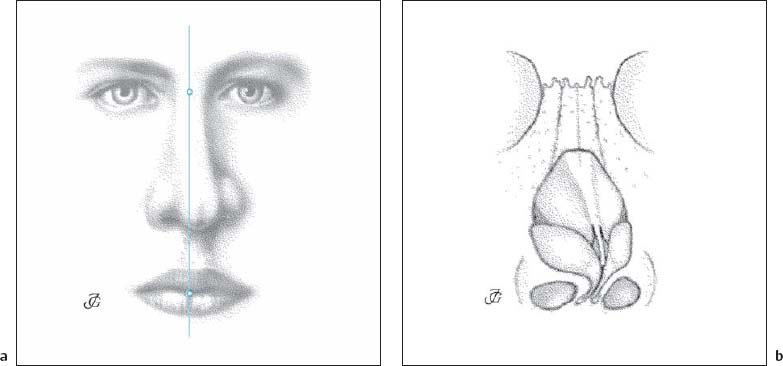

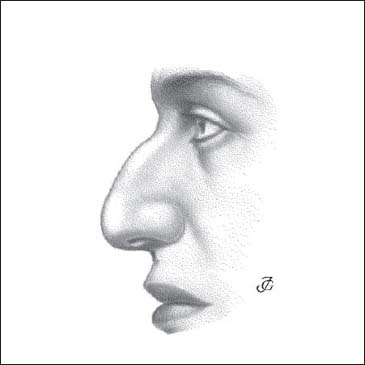

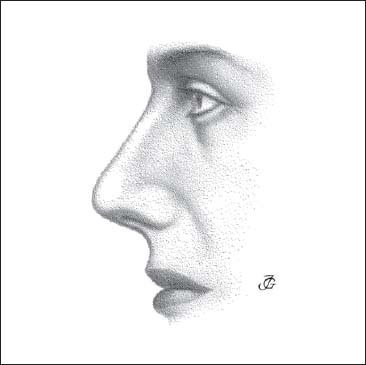

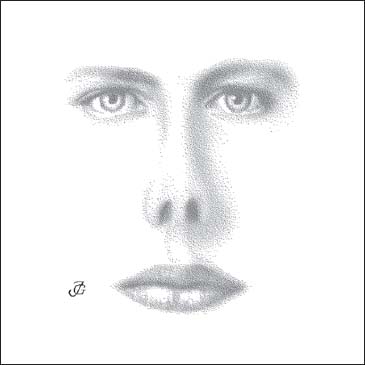

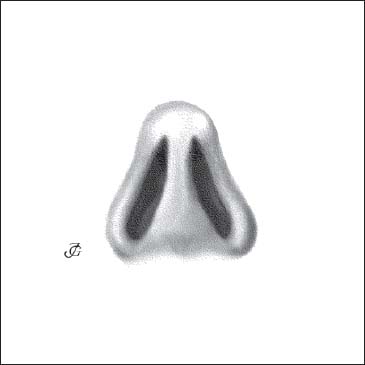

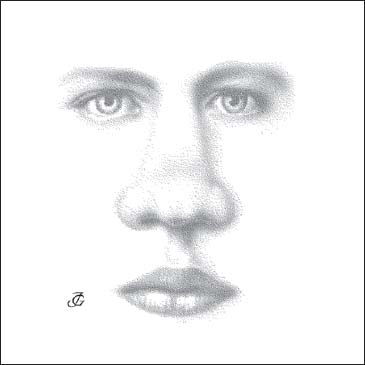

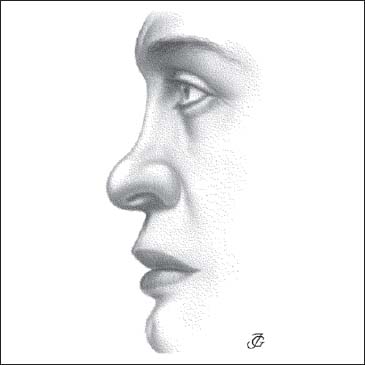

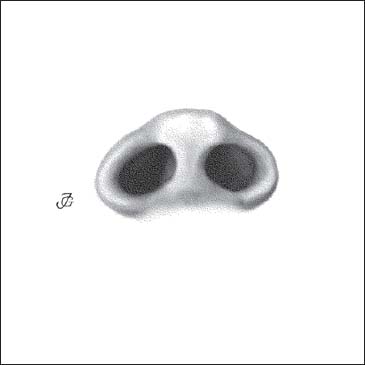

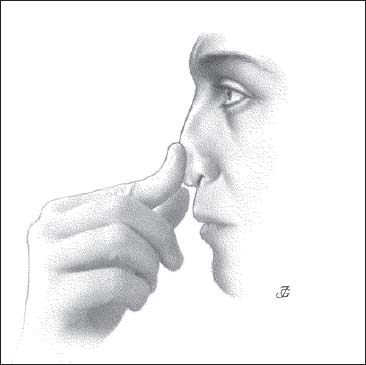

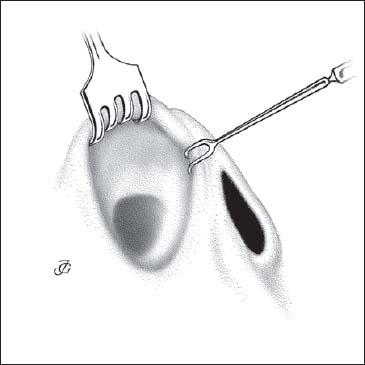

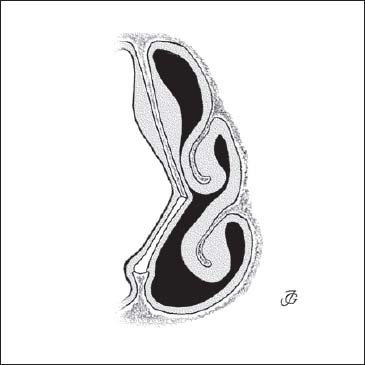

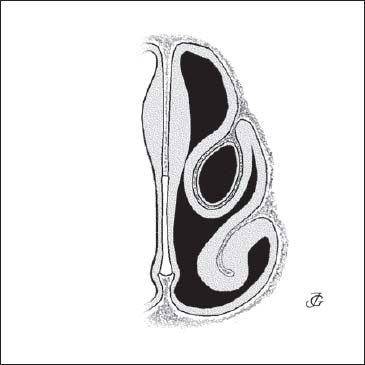

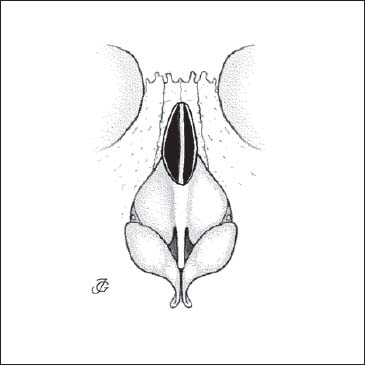

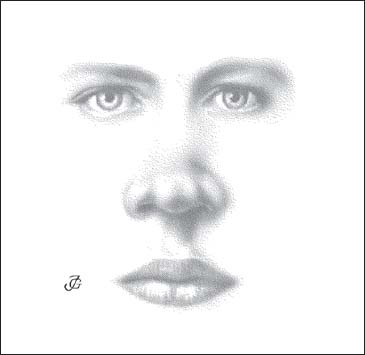

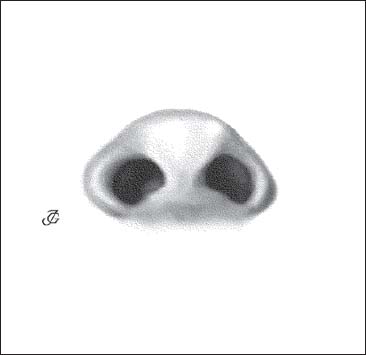

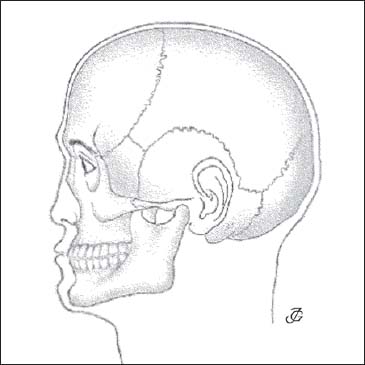

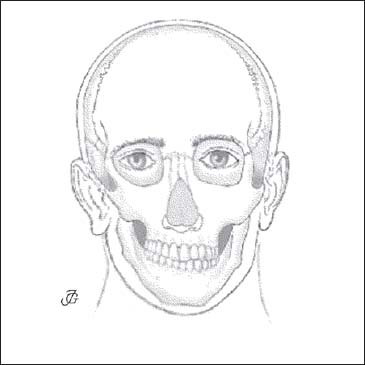

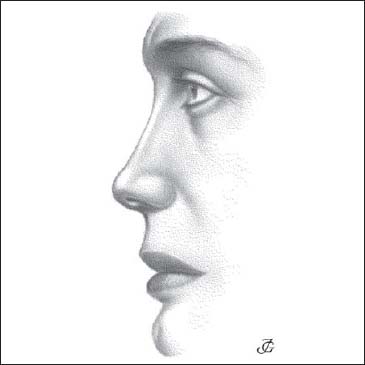

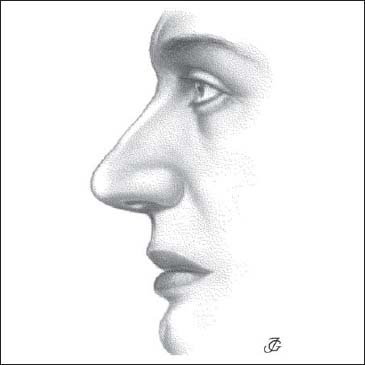

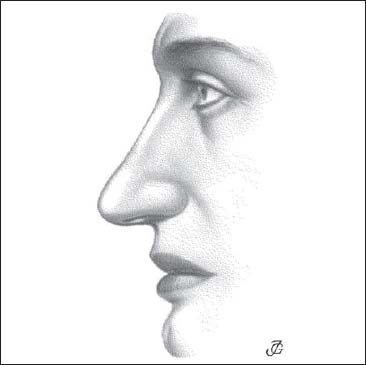

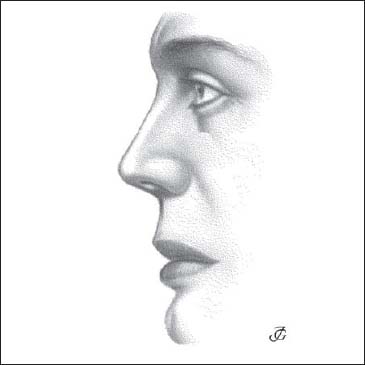

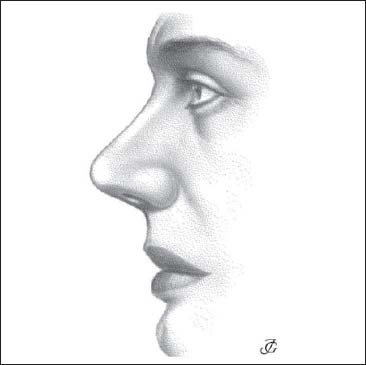

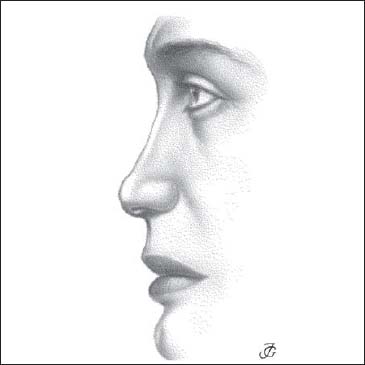

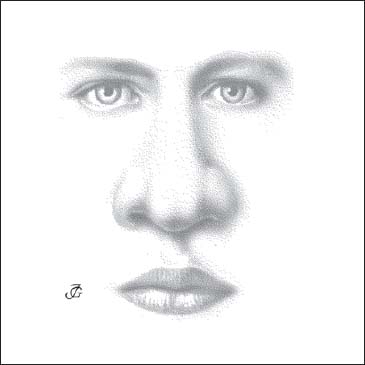

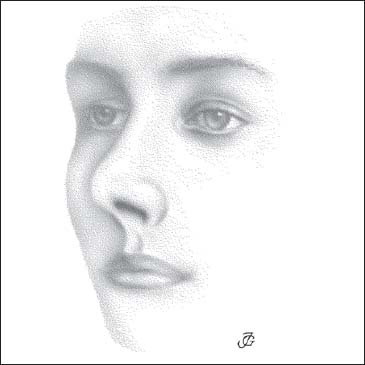

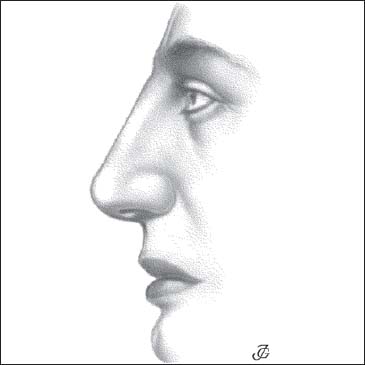

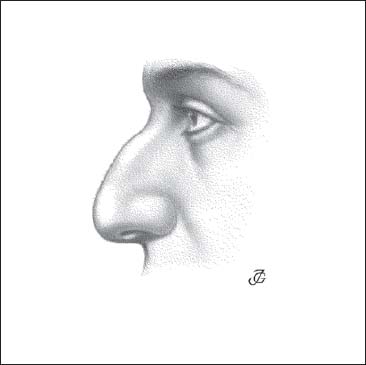

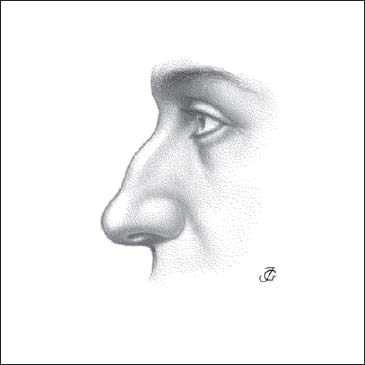

2 Pathology and Diagnosis In health and disease, signs and symptoms frequently occur in more or less fixed combinations. We then speak of a syndrome (in Greek, “syndrome” = “cometogether”). In the domain of functional corrective nasal surgery, we suggest distinguishing the following syndromes: The “deviated nose” is characterized by a deviation of the external nasal pyramid in combination with a deformity of the septum. In the great majority of patients, the underlying cause is mechanical trauma with a lateral, frontolateral, or laterobasal impact. A genetically deviated nose has been observed in some families. In rare cases, a deviated nose is of intrauterine origin. Patients with a deviating external nose generally have both functional and aesthetic complaints. Depending upon which part of the pyramid is deviated, we distinguish four types: Both the bony and the cartilaginous pyramid, and usually the lobule as well, deviate to one side (Figs. 2.1a, b). When the nasion–stomion line is drawn, deviation of all parts parts of the nasal pyramid becomes obvious. The bony pyramid leans to one side. It is asymmetric, with a short, steep slope on the side of the deviation (due to an infraction of the nasal bone) and a long, shallow slope on the opposite side. The cartilaginous pyramid is deformed in a similar way. The triangular cartilages are asymmetric, especially when the trauma occurred in childhood. Some sagging of the cartilaginous dorsum may be present. The lobule often leans to the same side. The tip deviates to the side of the deviation. The columella is oblique, with its upper part leaning to the side of the deviation. It may also be broadened, due to a dislocation of the caudal end of the septum. The alae differ in length and the nostrils are asymmetric. These lobular asymmetries are usually automatically corrected by repositioning of the septum and the cartilaginous pyramid. Only in patients with a long-standing severe deviation might additional lobular surgery be needed. The septum may show a variety of deformations. The anterior septum is usually dislocated to the side of the deviation, where as its posterior part is either in the midline or deviated to the contralateral side. The caudal septal end often protrudes into the vestibule, and the valve area may be narrowed by a septal convexity or fracture. A basal bony-cartilaginous crest and/or a vomeral spur are common. Breathing is generally impaired on both sides, the most severe symptoms occurring on the side of the valvular obstruction. The bony pyramid deviates to the right, where as the cartilaginous pyramid leans to the left. The lobule usually leans to the same side as the cartilaginous pyramid (Figs. 2.2a, b). This type of deformity is also called a “twisted” nose. The deformities of the various parts of the pyramid and the septum are similar to the ones described earlier. They may occur in different combinations, however. The bony pyramid deviates to the left, where as the cartilaginous pyramid leans to the right. The lobule usually deviates to the same side as the cartilaginous pyramid. (Figs. 2.3a, b). The bony pyramid is straight and symmetrical, where as the cartilaginous pyramid and lobule are deviated (Figs. 2.4a, b). This deformity is characterized by a more or less severe deviation and asymmetry of the cartilaginous pyramid in combination with a deviation of the anterior septum to the same side. The caudal septal end is usually dislocated to the side of the deviation and protrudes into the vestibule and nostril. The valve area is mostly obstructed by a fracture or a convexity of the septal cartilage. The posterior septum is normal or deviated. Inspiratory breathing is usually impaired, especially on the side of the compromised valve area. Fig. 2.2a, b C-shaped deviation of the pyramid. The bony pyramid deviates to the right, the cartilaginous pyramid and lobule lean to the left. The nasal dorsum is convex. This may concern the bony pyramid, the cartilaginous pyramid, and both the bony and cartilaginous pyramid. The nasal tip is often relatively low or depressed. A hump may occur as a single deformity or variation. It may also occur in combination with various types of septal and pyramidal pathology. A hump itself usually only causes aesthetic complaints. We distinguish the following types: Fig. 2.4a, b Deviated cartilaginous pyramid. The bony pyramid is normal, the cartilaginous pyramid and lobule are deviated These different types of humps are discussed and illustrated in more detail in the section on symptoms, page 74. The external nasal pyramid is (abnormally) prominent and narrow. The length and height of the external nose are usually greater than normal. The frontonasal angle is relatively small, and the nasolabial angle is larger than normal. The piriform aperture is high and narrow. The clinical nasal index is less than 70. The skull is dolichocephalic. Retrognathism of the mandible is a frequent feature. The prominent-narrow pyramid syndrome is a pronounced form of leptorrhinia. It is of genetic ethnic origin and common in Caucasians. It is seen more frequently in females than in males (Figs. 2.6–2.8). The entire external pyramid is narrow and prominent. The bony dorsum is straight or slightly humped, and the overlying skin is usually thin. The cartilaginous pyramid is narrow and prominent, and its dorsum is often slightly convex. The valve area is narrow and high and easily collapsible. The lobule is narrow and projecting. The tip is narrow and may be pulled down slightly by the tension of the stretched alae and columella. There is a positive “OO phenomenon” (see p. 102, Fig. 2.114). By puckering the lips, as when pronouncing the vowel sound “OO,” the tip is drawn down and backward due to the tension (overstretch) of the columella and the upper lip. Fig. 2.5 Bony and cartilaginous hump. Both the bony and cartilaginous pyramid are convex and projecting. The columella is relatively long and slender; the alae are thin and (over)stretched. The nares are more or less slitlike and their axis is almost vertical instead of oblique. As a consequence, the alae may collapse on inspiration. The septum is usually normal, although small deformations may be present. The upper lip is usually short, and retrognathism of the mandible is common. The patients may ask for surgery for aesthetic reasons. However, there may also be functional reasons: breathing impairment due to inspiratory collapse of the alae and/or obstruction of the valve area, for example. Cottle has named the prominent external pyramid the “tension nose.” He pointed out that the soft tissues are under tension as a result of the strong ventral growth of the septum and bony pyramid in comparison to the soft tissues. Fig. 2.6 Prominent-narrow pyramid syndrome. The entire external nasal pyramid is prominent, narrow, and long; the dorsum may be straight, slightly convex, or show a bony and cartilaginous hump; the lobule is narrow and projecting; the nasolabial angle is large. The saddle nose or the low-wide pyramid syndrome is either congenital (congenital nasal hypoplasia) or the result of severe septal pathology (trauma, septal abscess, inadequate septal surgery). The bony pyramid is broad and lacks prominence (Figs. 2.9, 2.10). The dorsum is flat. The nasal bones are usually thick. The bony pyramid is more or less round or trapezoid rather than pyramidal. The cartilaginous pyramid is low and wide. The clinical nasal index is more than 85. The cartilaginous dorsum sags, lacking support and projection (Figs. 2.9, 2.10). This is due to a defective anterior septum and scarring of the soft tissues. The triangular cartilages are often atrophic. The fibrous connections between the cartilaginous and the bony pyramid may have been lost, making the lower margins of the nasal bones visible. The lobule is underprojected and lacks support. Its shape resembles that of the lobule in childhood (Fig. 2.11). This is partially due to causative trauma or infection and partially the result of disturbed nasal growth. Because of the absence of (septal) support, the tip can easily be pressed downward—the so-called “rubber nose” phenomenon (Fig. 2.12). The tip is broad and flat. The columella is short and retracted, especially at its base. The alae are more convex and thicker than normal. The nostrils are round and ballooning. Fig. 2.7 The external pyramid is narrow and prominent; the lobule is narrow and projecting. Fig. 2.8 The nostrils are slitlike and their axis almost vertical; the columella is long and narrow; the alae are thin and stretched. Fig. 2.9 Low-wide pyramid syndrome. The external nasal pyramid is low and wide; the bony and cartilaginous pyramid are depressed and low; the nasal bones are thick; the lobule is low and wide. Fig. 2.10 The bony and cartilaginous pyramid are low; the nasal bones are thick; the lobule is low, wide, and underprojected. The vestibule and the valve area are broad and low (Fig. 2.13). The valve angle is depressed and considerably increased, sometimes even up to 90°. Patients with low, wide pyramid syndrome usually have both functional and aesthetic complaints. Their breathing is often disturbed, although their nasal passages are wide enough. Due to the deformity of the vestibule and the valve area, the inspiratory airstream will be less turbulent. This may compromise the air-conditioning and cleansing functions of the nose. The mucosa is usually of poor quality. The cilia may be partially missing, and mucociliary clearance is impaired, leading to local infection, crusting, and bleeding. All these factors will to some degree negatively influence nasal function. Fig. 2.11 The lobule is underprojected and broad. The tip is flat and depressed; the columella is short and retracted; the nostrils are wide and rounded; the alae are ballooning. Apart from being part of a syndrome, saddling and sagging may also occur in isolation as a symptom. We distinguish the following five types of saddle nose: The lobular inspiratory insufficiency syndrome is characterized by collapse of the lateral wall of the lobule during the inspiratory phase of breathing. As a result of negative pressure at inspiration, the lateral nasal wall is sucked inward and collapses. This condition was already recognized as a pathological entity in the second half of the 19th century and was called “alar collapse.” Alar collapse is a misleading term, however, and has induced many surgical mistakes. The collapse of the mobile lateral nasal wall is, in many cases, not due to alar weakness. The most common causes are as follows: Fig. 2.12 The lobule and tip lack projection and support. The lobule is easily compressed by pressing with the finger on the tip (so-called “rubber nose”). All these kinds of pathology, sometimes in combination, may lead to collapse of (parts of) the lateral wall of the lobule. For this reason, we prefer to speak of the “lobular inspiratory insufficiency syndrome.” Table 2.1 gives an overview of the most frequent causes. The middle meatus obstruction syndrome is characterized by a set of symptoms that may occur when the middle meatal paseage is obstructed. The main symptoms of this syndrome are: Fig. 2.13 The valve is low and very wide due to loss of the cartilaginous septum and retraction of the soft tissues of the septum. Fig. 2.14 Obstruction of the middle meatus by a septal deviation.

Nasal Syndromes

1. Deviated Nose Syndromes

1. Deviated Nose Syndromes

The bony and cartilaginous pyramid and lobule deviate to the same side.

The bony pyramid deviates to the right, the cartilaginous pyramid to the left.

The bony pyramid deviates to the left, the cartilaginous pyramid to the right.

The cartilaginous pyramid is deviated, where as the bony pyramid is in the midline.

Deviated Pyramid

C-Shaped Pyramid

Reversed C-Shaped Pyramid

Deviated Cartilaginous Pyramid

2. Hump Nose

2. Hump Nose

Both the bony and the cartilaginous dorsum are convex (humped). The maximum convexity is usually located at the K area (Fig. 2.5).

Bony hump

The convexity is confined to the bony pyramid (see Fig. 2.36).

The convexity is limited to the cartilaginous dorsum (see Fig. 2.37).

The bony dorsum is projecting due to saddling of the cartilaginous pyramid (see Fig. 2.38).

3. Prominent-Narrow Pyramid Syndrome (Tension Nose)

3. Prominent-Narrow Pyramid Syndrome (Tension Nose)

4. Low-Wide Pyramid Syndrome (Saddle Nose)

4. Low-Wide Pyramid Syndrome (Saddle Nose)

The bony pyramid is concave where as the cartilaginous dorsum is normal (see Fig. 2.40).

The cartilaginous dorsum is concave and depressed, while the bony dorsum is normal (see Figs. 2.41, 2.42).

A linea nasalis is a pathological horizontal crease over the cartilaginous dorsum just above the lobule (see Fig. 2.45).

The cartilaginous pyramid is detached from the bony pyramid. The junction between the triangular cartilages and the nasal bones is disrupted (see Fig. 2.43).

The area just cranial to the tip is depressed (see Fig. 2.44).

5. Lobular Inspiratory Insufficiency Syndrome (“Alar Collapse”)

5. Lobular Inspiratory Insufficiency Syndrome (“Alar Collapse”)

6. Middle Meatus Obstructive Syndrome

6. Middle Meatus Obstructive Syndrome

| Nostril | slitlike nostrils (prominent, narrow pyramid syndrome) |

| Nostril vestibule | broad columella protruding medial crura dislocated and protruding caudal septal end |

| Vestibule | protruding lateral crus |

| Valve area | stenosis due to: —septal pathology —synechiae —triangular cartilage pathology —hyperplasia of inferior turbinate head |

| Septum | deviation or thickening opposite the middle turbinate |

| Middle turbinate | concha bullosa or spongiosa lateral curling |

| Uncinate process | long and/or medially curled |

| Ethmoidal bulla | large ventral location |

| Infundibulum | narrow |

| Mucosa | swelling polypoid degeneration |

Obstruction of middle meatal areas has diverse causes, both anatomical and pathological. Analysis of the factors contributing to the syndrome is of utmost importance in selecting the mode of treatment. The following anatomical features may be involved: the septum, middle turbinate, uncinate process, ethmoidal bulla, infundibulum, and the mucosa overlying these structures. Table 2.2 gives an overview of the most common causes.

Septum

A deviation or a thickening of the septum in area 4 at the level of the head of the middle turbinate can easily lead to temporary or permanent contact between the septal and turbinate mucosa. Septal surgery may be helpful in these cases (Fig. 2.14).

Middle Turbinate

Concha bullosa is a normal anatomical variation found in about 25% of the population. The turbinate skeleton may be very thick and spongiotic. In combination with other conditions, these variations can play a major role in the development of an obstructive syndrome (Fig. 2.15). Middle turbinate surgery might then be indicated.

Fig. 2.15 Obstruction of the middle meatus by a bullous middle turbinate.

Uncinate Process

The uncinate process may follow a medial instead of a lateral course. Its end may also be curved medially downward, suggesting the presence of a second, more laterally localized medial turbinate. These variations can easily contribute to obstruction of the middle meatus.

Ethmoidal Bulla

The size and location of the ethmoidal bulla will show considerable interindividual variation. When large and relatively more ventral than average, it may be in more or less permanent contact with the middle turbinate or the lateral wall of the infundibulum. In this case, it will obstruct the entrance to the infundibulum.

Infundibulum

The depth and width of the infundibulum may be another cause of the middle meatus obstruction syndrome.

Nasal Mucosa

Allergy, hyperreactivity, and infection will induce mucosal swelling. This may lead to contact between the septum and the middle turbinate as well as to obstruction of the infundibulum and ostiomeatal complex. In chronic conditions, hyperplasia and polypous degeneration may result.

In mild cases, conservative treatment (antibiotics, corticosteroid sprays) is prescribed. Polyps resistant to conservative treatment have to be resected, and infundibulotomy and/or anterior ethmoidectomy may be indicated. A septal deformity and concha bullosa may be addressed during the same surgical procedure.

7. Open Roof Syndrome

7. Open Roof Syndrome

The open roof syndrome is characterized by neuralgic symptoms that are caused by a traumatic defect in the bony (and cartilaginous) dorsum. The most common cause is resection of a bony and/or cartilaginous hump with subsequent closure of the dorsum. Cottle was the first to describe this syndrome as an entity.

Its main symptoms are tenderness of the bony dorsum, pain when wearing eyeglasses, and pain sensations when inspiring cold air. On examination, an irregular defect in the bony dorsum and K area can be seen and palpated through a thin and adherent skin with teleangiectasias.

These symptoms are caused by a defect in the bony roof and damage to the external nasal branches of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (Fig. 2.16). As a result of the defect, the outside skin and the inside nasal mucosa are in direct contact, which may induce neuralgia. Evidence for this pathogenetic explanation is found in the fact that the symptoms disappear after secondary closure of the dorsum through osteotomies and interposition of a layer of connective tissue or soft cartilage between the skin and the bony defect.

8. Wide Nasal Cavity Syndrome (“Empty Nose” Syndrome)

8. Wide Nasal Cavity Syndrome (“Empty Nose” Syndrome)

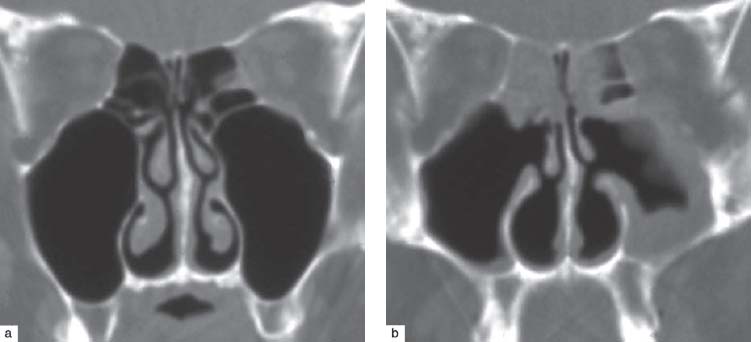

The wide nasal cavity syndrome may occur when too much of the inferior and/or middle turbinate has been resected (Fig. 2.17). Stenquist and Kern (1996) have recently drawn attention to the characteristic symptoms and findings of the iatrogenically induced wide nasal cavity. They introduced the term “empty nose syndrome.” The wide nasal cavity secondary to endonasal surgery has become more and more common in recent years, as (sub)total turbinectomy has again become popular. Patients with a secondary wide nasal cavity may suffer from a variety of complaints: for instance, a feeling of nasal obstruction in spite of normal breathing; nasal irritation and itching; headaches and pressure feelings; radiating pain on inspiring cold air; crusting; and minor blood loss. The severity of these complaints differs considerably from person to person. Some patients have only minor symptoms, where as others are real “nasal cripples.”

On examination, the nasal cavity is abnormally spacious, lacking (part of) one or both turbinates. Mucosal pathology varies greatly. In some patients, the mucosa is dry and pale because of metaplasia; in others, it is red because of chronic infection. Crusting may range from absent to severe. The symptoms and findings are believed to be caused by abnormal air currents due to the disturbed anatomy. In many cases, however, the discrepancy between the degree of the anatomical disturbance and the severity of the symptoms is difficult to understand.

Fig. 2.16a Defect of dorsum (open roof) visible through the skin.

Fig. 2.16b Defect of dorsum (open roof) after resection of a bony and cartilaginous hump.

Fig. 2.17a, b Wide nasal cavity syndrome or empty nose syndrome. Coronal CT scans before (a) and after (b) bilateral infundibulotomy and resection of the inferior turbinates. Note the reactive swelling of the mucosal lining of the ethmoids and left maxillary sinus to compensate for the abnormally wide space.

Fig. 2.18b The bony pyramid leans to the NCS, where as the cartilaginous pyramid and lobule deviate to the CS. The lobule is severely asymmetrical. The ala on the CS is flattened and displaced, and the lateral crus of the lobular cartilage is lower, less convex, and located more caudally.

9. Dry Nose Syndrome

9. Dry Nose Syndrome

The dry nose syndrome is found in primary and secondary atrophic rhinitis. Primary atrophic rhinitis may occur as part of a systemic syndrome or may be of unknown origin. Secondary atrophic rhinitis is much more common. It is mostly iatrogenic, resulting from a loss of normally functioning mucosa following electrocoagulation, chemocautery, or laser treatment of the inferior turbinates. Septal surgery without proper septal reconstruction may be an additional factor. The symptoms include nasal irritation, itching, and a feeling of dryness. Some crusting and minor nose bleeds may occur too.

10. Cleft Lip and Palate Nose

10. Cleft Lip and Palate Nose

A cleft lip and/or cleft palate is one of the most common congenital anomalies. Its treatment is one of the most difficult challenges to the maxillofacial and nasal surgeon. The deformity consists of a unilateral or bilateral defect of the upper lip, alveolar process of the maxilla, and/or palate. Unilateral clefts are much more common than bilateral clefts.

Incidence

The incidence of the cleft lip and palate varies considerably by region and ethnic group. According to recent literature, the incidence lies between 0.3 per million (American Indians, Japanese) and 2.5 per thousand (Blacks in Nigeria and South Africa).

Etiology

A positive family history can be found in about a quarter of the cases. External factors are assumed to play a causative role in other cases. When they occur before the sixth week of gestation, they may lead to a complete syndrome. When occurring later but before the 10–12 th week, an isolated palatal defect will occur (see Chapter 1, p. 44).

Pathology

When analyzing the nose and its adjacent structures we find that almost all nasal elements are more or less affected. In general, the nasal pathology in the cleft lip and palate shows a typical pattern, but considerable variations may occur. The main causes of this variability are the width of the cleft and previous surgery. The type of surgery by which the lip and palate have been closed as well as the period in life when the surgery was performed are the main determining factors.

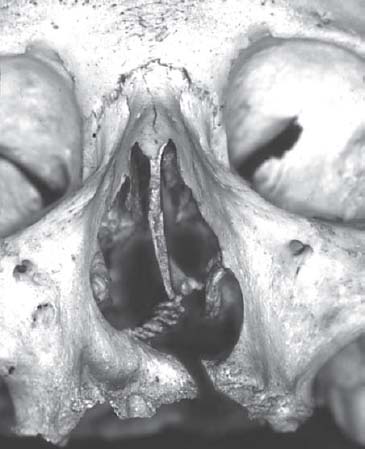

Fig. 2.18c Skull with cleft on the left side. The piriform aperture on the CS is lower and narrower. The anterior nasal spine and the premaxilla are strongly deviating to the CS. A pronounced crest and spur are present on the CS. The bone of the inferior turbinate on the CS is lower and more lateral than on the NCS (photo courtesy of Prof. Pirsig).

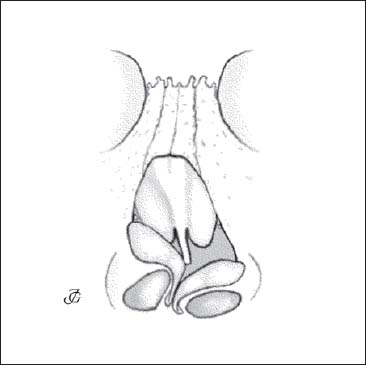

Bony and Cartilaginous Pyramid

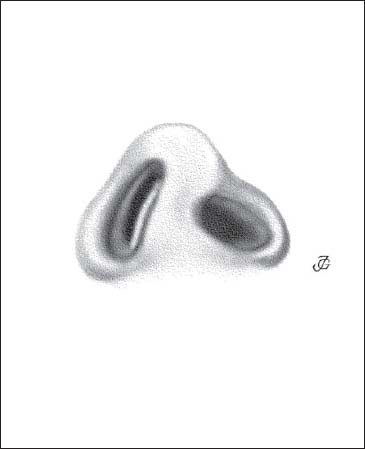

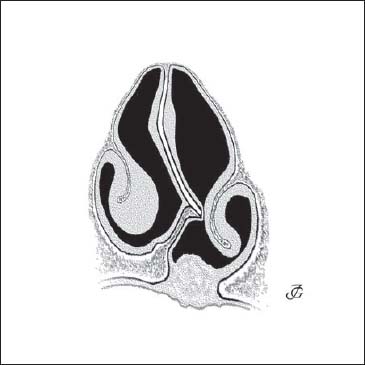

The bony and cartilaginous pyramid are asymmetric and lean slightly to the non-cleft side (NCS), as shown in Figures 2.18a, b. The piriform aperture is asymmetric, the aperture on the cleft side (CS) being lower and narrower. The anterior nasal spine deviates to the CS or may be missing. The premaxilla is severely deviated under an angle of 45° to the CS (Fig. 2.18c).

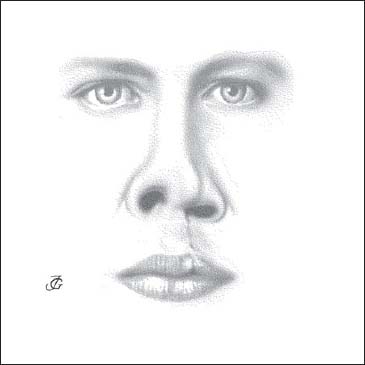

Lobule

The lobule is severely asymmetrical and shows various specific deformations (Figs. 2.18a, b, d). The tip is bifid and flat, the dome and lateral crus of the lobular cartilage on the CS being more depressed. The ala on the CS is elongated, flat, and displaced in a lateral and caudal direction. Its axis is more horizontal. The vestibule is narrow. The columella is short, broad, and oblique. Its upper end leans to the CS, its base is retracted. The lateral crus on the CS is lower, less convex, and more caudally located than on the NCS. The medial crus on the CS is somewhat displaced in a caudal direction (Fig. 2.18b).

Fig. 2.18d The lobule is severely asymmetrical: the dome and lateral crus on the CS are depressed and rotated in an anterior direction. The nostril is ovaloid and has an almost transverse axis. The vestibule is narrow. The columella is short and deviating to the CS. The caudal septum is deviating to the NCS.

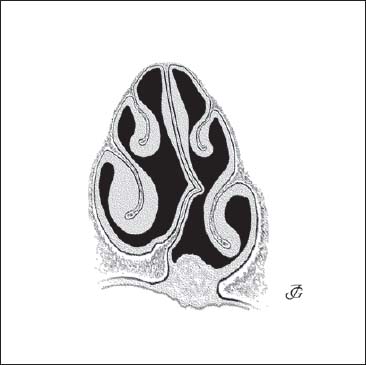

Septum

The septum is severely deformed. Its caudal end is dislocated to the NCS and may thereby narrow the vestibule on this side. More posteriorly, the cartilaginous septum, vomer, and perpendicular plate are strongly deviating to the CS, thereby obstructing the valve area and the nasal cavity. At the chondropremaxillary and perpendicular–vomeral junction, a pronounced cartilaginous and bony crest is present (Figs. 2.18c, e, f). The depressed ala usually contributes to the stenosis of the valve area.

Turbinates

The inferior turbinate on the CS is lower and compressed in a lateral direction. Its bony lamella is lower than normal. On the NCS, the inferior turbinate is usually compensatory hypertrophied. The middle turbinate on the CS is generally somewhat more slender than on the NCS (Figs. 2.18e, f).

Fig. 2.18f Deformity of the septum and turbinates at the level of the vomer. The perpendicular plate and vomer deviate to the CS. A pronounced crest and spur are usually present at the chondrovomeral and the perpendicular–vomeral junction. The inferior turbinate on the CS is compressed and positioned lower. The inferior turbinate on the NCS is usually compensatorily hypertrophied.

11. Congenital Nasal Hypoplasia (Nasomaxillary Dysplasia, Binder Syndrome)

11. Congenital Nasal Hypoplasia (Nasomaxillary Dysplasia, Binder Syndrome)

This syndrome is characterized by a congenital underdevelopment of all nasal structures in combination with maxillary hypoplasia or retrusion. It is relatively rare and sporadic. In most cases, the cause is unclear. The bony and the cartilaginous pyramid are low, wide, and underprojected. The lobule is flat and wide. The nostrils vary greatly its shape from round to square and have a transverse axis. The tip is broad and sometimes bifid, the columella is short and broad, and the alae are abnormally convex (Figs. 2.19a, b). The septum is underdeveloped in an anterior and caudal direction and may be partially missing. The maxillary bones are hypoplastic and the midface is retruded (Fig. 2.20). The anterior nasal spine is usually missing. This syndrome is sometimes called Binder syndrome (Binder 1962).

Fig. 2.19a Congenital nasal hypoplasia. The bony pyramid, cartilaginous pyramid, and lobule low, wide, and short.

Fig. 2.19b The nostrils are square; the tip is broad and sometimes bifid; the columella is short and broad; the alae are round and abnormally convex.

Fig. 2.20 The midface is underdeveloped and retruded.

12. Facial Syndromes

12. Facial Syndromes

Facial Asymmetries

The following facial asymmetries may be distinguished: the long-face syndrome, the short-face syndrome, maxillary protrusion, maxillary retrusion (midface hypoplasia), mandibular prognathism, and mandibular retrognathism. In this paragraph we restrict ourselves to a discussion of the syndromes that have a great impact on the analysis and surgical correction of nasal deformities.

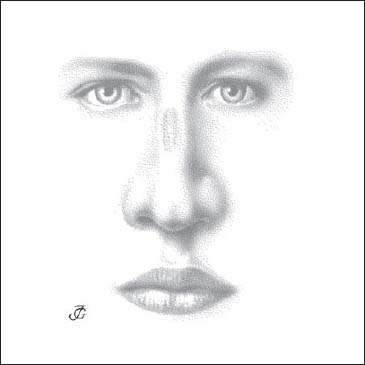

Left–Right Facial Asymmetry

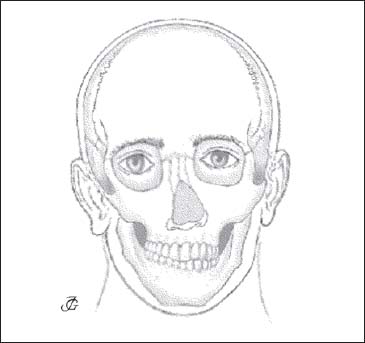

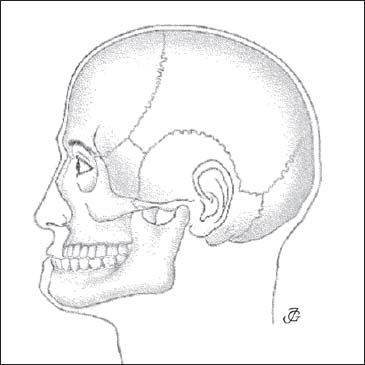

Various elements of the skull and face are asymmetrical between the right and the left. Two examples are presented in Figures 2.21 and 2.22, showing that the middle and lower part of the face is concave on the right. The external ear canal and auricle on the right are located lower than on the left side. The maxillary bones are asymmetrical, with a relative retroposition on the right. The mouth is displaced to the right, the left corner being somewhat lower than the right one. The mandible is asymmetrical. The chin is displaced to the right. Because of the severe facial asymmetry, it is difficult to determine whether the nose is in the midline or deviated. For instance, when the trichion–nasion–stomion–gnathion line is drawn, the nose seems to be deviating to the left. When the trichion–nasion-tip line is drawn, the external pyramid appears straight. Both cases stress the importance of careful facial analysis. It is crucial to determine the position of the external pyramid in relation to the other facial structures.

Fig. 2.21 Asymmetry of the middle and lower thirds of the face suggesting a severely deviating external nasal pyramid. In reality there is only a limited septal and pyramid deviation.

Fig. 2.22 A similar case to Figure 2.21 showing a combination of a deviation of the nose to the left and a concavity of the face to the right.

Fig. 2.23 Retroposition of the maxilla.

Maxillary and Mandibular Retrusion

Maxillary Retrusion (Retroposition)

The maxilla bone is bilaterally or unilaterally retropositioned with respect to the frontal bones and the nasal pyramid. A bilateral retroposition of the maxilla and cheek accentuates the degree of prominence (projection) of the nose in relation to the face. A unilateral retropositioning may give (or accentuate) the impression that the external nose is leaning to that side. Retroposition of the maxilla may be examined clinically by studying the face from above with a flat object on both cheeks (Fig. 2.23). Exact measurements may be made by x-ray cephalometry.

Mandibular Retrusion (Retroposition or Retrognathia)

Retrusion of the mandible or retrognathia is a common feature of the dolichocephalic skull. It is frequently seen in Caucasians (Fig. 2.24). Retroposition of the mandible visually accentuates the prominence of the nasal pyramid. In these patients a “let-down” of the pyramid is therefore often combined with a mentoplasty.

13. Nasal Neuralgia

13. Nasal Neuralgia

Nasal or sinus disease is the most common cause of facial pain and headache. Branches of the palatine nerve become irritated, producing pain and pressure sensations that may be felt in a wide area of the head. It is customary for laymen and doctors alike to suspect some kind of “sinusitis.” In many cases, however, the cause is found in the septum and the turbinates. Two syndromes may be distinguished:

- pterygopalatine neuralgia or Sluder syndrome;

- anterior and/or posterior ethmoidal neuralgia.

Fig. 2.24 Retroposition of the mandible.

Pterygopalatine Neuralgia (Vidian Neuralgia or Sluder Syndrome)

Branches of the pterygopalatine nerve (posterior-superior and posterior-inferior lateral nasal branches or posterior septal branches) become irritated by pressure or infection. The most common symptoms are homolateral, deep pain or pressure feelings localized paranasally and around the orbit, sometimes radiating towards the forehead and the back of the skull. This type of cephalic neuralgia was first described as a specific entity by Greenfield Sluder (1908, 1913, 1927) and is therefore often referred to as Sluder syndrome. It is also called Vidian neuralgia.

Its most common cause is impaction of a septal deformity (usually a spur) into the posterior part of the inferior turbinate. Other causes may be a new growth, a foreign body, or an infection of the posterior-inferior half of the nasal cavity.

Diagnosis of pterygopalatine neuralgia is confirmed by the immediate relief of symptoms when the pterygopalatine ganglion is anesthetized (preferably with crystalline cocaine on the tip of a cotton-wool applicator; see p. 120 and Fig. 3.5). The more precisely localized the anesthesia, the better this type of neuralgia can be distinguished from other types such as ethmoidal neuralgia. If a septal impaction is incriminated as the likely cause of the Sluder type of neuralgia, a test with local decongestion may be tried before applying anesthesia. If the pain stops when the turbinate is simply detached from the septum, the pain can be attributed to the septoturbinate contact. Septal surgery will then most likely be an effective treatment.

Anterior (Posterior) Ethmoidal Neuralgia

A similar syndrome may occur when branches of the anterior or posterior ethmoidal nerve are involved. Pain and pressure feelings are then perceived in and around the bony pyramid and nasal root, paranasally, medially, and posteriorly in the homolateral orbit and the forehead. Ophthalmological symptoms frequently occur. The syndrome may then be called Charlin syndrome or nasociliary neuralgia (Charlin 1930). Its most common cause is obstruction of the middle nasal passage or the infundibulum, as discussed and illustrated in the section on the middle meatal obstructive syndrome. Another variant of anterior ethmoidal neuralgia is the open roof syndrome (see previous text).

Nasal Symptoms—The Most Common Deformitites, Abnormalities, and Anatomical Variations

The human nose is subject to a wide array of deformities, abnormalities, and anatomical variations.

Deformity: Whether we are dealing with a deformity is rarely a matter of discussion. Congenital malformations of the nose like those in cleft-lip patients, nasal hypoplasia, or bifidity are clearly deformities. The same applies to acquired anomalies of the nose as may occur after trauma, infection, or new growth. A deviated nose, saddle nose, open roof, retracted columella, and septal deviation, to name a few, are considered to be deformities.

Abnormality: An abnormality may be defined as a “pathological anatomical change.” Frequently, an abnormality implies functional disturbance. This is not always the case, however. Generally, a slight post-traumatic sagging of the cartilaginous dorsum, flaccid alae, and an overprojected tip are abnormalities.

Anatomical variation: Deciding when an anatomical condition should be considered an anatomical variation may be more difficult, as this is often a matter of personal opinion. Many variations are, to a certain extent, dependent on race, gender, or age and have therefore to be considered within the normal range.

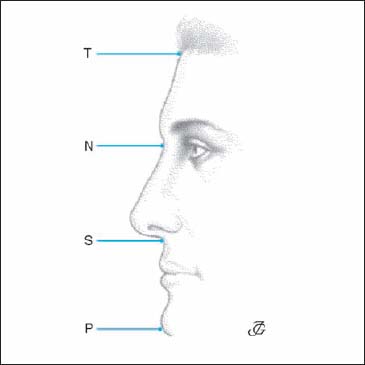

Fig. 2.25 Normal facial dimensions.

T = trichion, N = nasion, S = subnasale, and P = pogonion.

The distance T–N equals N–S equals S–P.

Pathology and Variations of Nasal Dimensions

Pathology and Variations of Nasal Dimensions

The human external nose may vary considerably in all its dimensions. The interindividual differences are determined by ethnic factors, gender, age, and pathological influences due to injury and infection. We define these differences in terms of: size (small–large), length (long–short), height, prominence (prominent–low), and width (wide–narrow).

Small Nose (Fig. 2.26)

The distance nasion–subnasale is less than the distance trichion–nasion and/or the distance subnasale–pogonion. A small nose is generally short, wide, and low at the same time. A small nose may be caused by congenital hypoplasia or impaired nasal growth, either as a result of a septal abscess or a severe septal trauma in childhood.

Fig. 2.26 Small nose

Fig. 2.28 Long nose

Fig. 2.29 Short nose

Fig. 2.30 Prominent nose

Large Nose (Fig. 2.27)

The distance nasion–subnasale is larger than the distance trichion–nasion and/or the distance subnasale– pogonion. A large nose is usually long and prominent. Its origin is mostly genetic, although endocrine factors (e.g. acromegaly) may play a role.

Long Nose (Fig. 2.28)

The distance nasion–tip is abnormally large, often in combination with excessive height. The pyramid may be prominent and narrow, and the tip is often drooping. The nasiolabial angle is more acute than average. A long nose may be caused by genetic as well as endocrine factors. The external nasal pyramid tends to lengthen with increasing age. A long nose may also result from surgery when a dorsal hump has been resected without shortening nasal length.

Short Nose (Fig. 2.29)

The distance nasion–tip is shorter than normal. This is always combined with a diminished height. The pyramid is generally wide and less prominent than normal. The nasolabial angle is relatively large. A short nose is seen in patients with congenital nasal hypoplasia or impaired nasal growth. It may also occur after surgery where the nasal tip has been upwardly rotated too much.

Prominent Nose (Fig. 2.30)

The projection (prominence, salience) of the external nasal pyramid is greater than normal. Usually, the nose is long and narrow.

Low Nose (Fig. 2.31)

The projection of the nasal pyramid is less than normal. In most cases, the nose is also short and wide. A low nose is often combined with a concave nasal dorsum. We then speak of a saddle nose, a sagging dorsum, or a low-wide pyramid syndrome (see also Figs. 2.9–2.13).

Wide Nose (Fig. 2.32)

The width (horizontal dimensions) of the nasal pyramid is abnormally large. In most cases, the bony pyramid, the cartilaginous pyramid, and the lobule are unusually wide. Usually, the nose is both shorter and less prominent than normal.

Narrow Nose (Fig. 2.33)

The width of the nasal pyramid is small. This condition is generally combined with a greater length and prominence. We then speak of a prominent, narrow pyramid syndrome (see also Figs. 2.6 and 2.7).

Fig. 2.32 Wide nose

Fig. 2.33 Narrow nose

“Greek Nose” (Fig. 2.34)

The forehead and nasal dorsum are almost in line. The frontonasal angle is almost 180°. This profile was adopted in ancient Greece as the ideal and used in sculptures of gods and heroes.

Fig. 2.35 Bony and cartilaginous hump

Fig. 2.36 Bony hump

Humps

Humps

A hump is a convexity of the nasal dorsum. When both the bony and the cartilaginous pyramid are involved, we speak of a hump nose. To a certain extent, a hump nose may be considered a syndrome (see p.  ff), though a hump may also occur in isolation as a deformity or variation. Sometimes it is seen along with pathology of the septum and pyramid. We distinguish the bony hump, the cartilaginous hump, a combination of these two, and the relative hump or pseudohump.

ff), though a hump may also occur in isolation as a deformity or variation. Sometimes it is seen along with pathology of the septum and pyramid. We distinguish the bony hump, the cartilaginous hump, a combination of these two, and the relative hump or pseudohump.

Bony and Cartilaginous Hump (Fig. 2.35)

Both the bony and the cartilaginous dorsum are convex (humped). The maximum convexity is usually located at the K area. This type of hump may be of genetic or traumatic origin. In various ethnic groups, a convex nasal dorsum is normal.

Bony Hump (Fig. 2.36)

The convexity is confined to the bony pyramid. A bony hump is usually due to previous trauma or to inadequate surgery.

Cartilaginous Hump (Fig. 2.37)

The convexity is limited to the cartilaginous dorsum. A cartilaginous hump is usually of traumatic origin. It may also be of genetic origin or occur as a side effect of inadequate lobular surgery, resulting in loss of tip projection.

Relative Bony Hump (Fig. 2.38)

The bony dorsum seems overprojected due to saddling of the cartilaginous pyramid. The convexity of the bony dorsum is relative, which means we are dealing with a pseudohump. The condition is often misdiagnosed by both patient and doctor. The underlying cause is usually a defective anterior septum. Treatment must therefore consist of septal reconstruction with an additional transplant rather than resection of the pseudohump.

Saddling and Sagging

Saddling and Sagging

Saddling (a saddle) and sagging denote concavity of the nasal dorsum. This is often due to extensive pathology such as the low-wide pyramid syndrome (see p. 60

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree