Chapter 19 Panniculitis

1. What is panniculitis?

Panniculitis represents infiltration of subcutaneous tissue by inflammatory cells, neoplastic cells, or both. This condition presents clinically as a deep induration or swelling of the skin. Associated signs and symptoms may include erythema, ulceration, drainage, warmth, and pain. Under certain circumstances, induration or nodularity may be present without significant inflammation or may persist after the inflammation has largely subsided.

2. Name the various types of panniculitis. How are they classified?

Although no single classification seems to be totally satisfactory, disorders tend to be grouped by a combination of histopathologic features and etiologies (Table 19-1). Septal panniculitis refers to a predominance of inflammation involving the connective tissue septae between fat lobules, whereas lobular panniculitis indicates predominant involvement of the fat lobules themselves. Lipodystrophy and lipoatrophy may be end-stage changes of the fat brought about by several different etiologies, including inflammation, trauma, or metabolic or hormonal alterations.

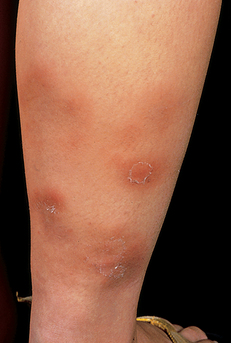

3. What is erythema nodosum?

Erythema nodosum (Fig. 19-1) consists of an eruption of erythematous, tender nodules—typically over the pretibial areas but occasionally elsewhere—that is regarded as a hypersensitivity response to some antigenic challenge. It is typically an acute process lasting 3 to 6 weeks, but a more chronic form can occur. Some experts consider the condition termed subacute nodular migratory panniculitis (Vilanova’s disease) to be a chronic variant of erythema nodosum.

Table 19-1. Major Forms of Panniculitis

| Septal Panniculitis Lobular and Mixed Panniculitis Metabolic Derangements | Traumatic Panniculitis Infectious Panniculitis Malignancy Other Changes of the Fat Lipodystrophy Lipoatrophy Lipohypertrophy |

Figure 19-1. Typical lesion of erythema nodosum on the leg. Erythema nodosum heals without scarring.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

4. What is the pathogenesis of erythema nodosum?

Erythema nodosum is usually considered to represent a delayed hypersensitivity response that reflects a common reaction pattern to a wide variety of eliciting factors. The subcutaneous septa in well-developed lesions often contain granulomas, and recent work has shown a strong correlation between genetic polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor–α and erythema nodosum (TNF-α promotes granuloma formation). Reactive oxygen intermediates may be involved in the tissue damage and inflammation that accompany erythema nodosum.

5. List some of the common underlying conditions associated with erythema nodosum.

Streptococcal infection of the upper respiratory tract and medications (especially oral contraceptives, sulfonamides, penicillins, bromides, and iodides) are among the most common known causes. Other triggers include deep fungal infections (such as coccidioidomycosis), Yersinia infection, pregnancy, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and leukemia. Many episodes are idiopathic: A cause is not identified in one third to one half of cases.

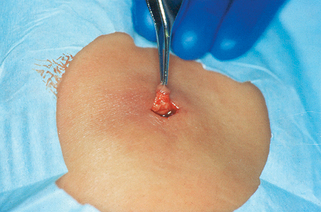

6. How should a biopsy of erythema nodosum be obtained?

The specimen should be obtained from the most fully developed (central) portion of the lesion (Fig. 19-2). It is absolutely critical that the biopsy be deep enough to incorporate subcutaneous fat. Incisional biopsies that include a generous horizontal expanse of subcutis are preferred to small punch biopsies.

7. What are the characteristic microscopic features of erythema nodosum?

The typical histologic features include a predominantly septal panniculitis with a slight spillover of inflammatory cells into the fat lobules. Cell types may include lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, especially in acute disease. In older lesions, small granulomas (Miescher’s granulomas) are sometimes observed within connective tissue septa. Perivascular infiltrates are common, but true vasculitis with destruction of vessel walls is not observed.

8. How is erythema nodosum treated?

Treatment of the underlying disorder, if known, is of primary importance. Salicylates or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, bed rest, and potassium iodide (particularly in chronic forms of the disease) are usually considered to be first-line therapies while colchicine, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, and prednisone are second-line therapies used in recalcitrant cases.

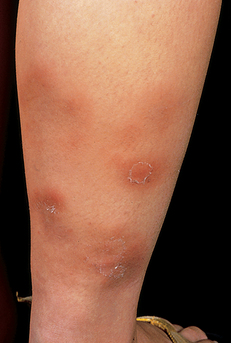

9. What is nodular vasculitis?

This form of panniculitis most commonly occurs on the posterior lower legs (Fig. 19-3), as opposed to the classically anterior location of erythema nodosum. Ulceration and drainage sometimes occur.

10. What causes nodular vasculitis?

It was originally considered a hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculosis and termed erythema induratum of Bazin. Studies confirm that in many cases Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA can be detected in the lesions by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); however, nodular vasculitis can also be idiopathic or associated with other infectious agents (Nocardia, hepatitis C) or drugs (propylthiouracil). These cases with nontuberculous etiologies are sometimes termed erythema induratum of Whitfield.

Figure 19-3. Erythema induratum demonstrating characteristic indurated subcutaneous nodules. Spontaneous ulceration is common.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

Key Points: Panniculitis

1. Given the similar clinical appearance among panniculitides, histopathologic characterization is often critical for a correct diagnosis.

2. An incisional biopsy with a wide base in the fat is far more likely to be diagnostic than a deep shave or punch biopsy.

3. The biopsy should be taken from the most indurated lesion; if that lesion has an ulcer, the biopsy should avoid the ulcer base.

Key Points: Erythema Nodosum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree