Chapter 12 Panniculectomy and Abdominal Wall Reconstruction ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

1 Relevant General Anatomy

When considering panniculectomy in the setting of abdominal hernia repair, the underlying musculature, aponeurotic layers, and adipocutaneous structures are important. The three components are interrelated and should be addressed systematically in order to optimize outcomes following panniculectomy.

When considering panniculectomy in the setting of abdominal hernia repair, the underlying musculature, aponeurotic layers, and adipocutaneous structures are important. The three components are interrelated and should be addressed systematically in order to optimize outcomes following panniculectomy.2 Relevant Muscular Anatomy

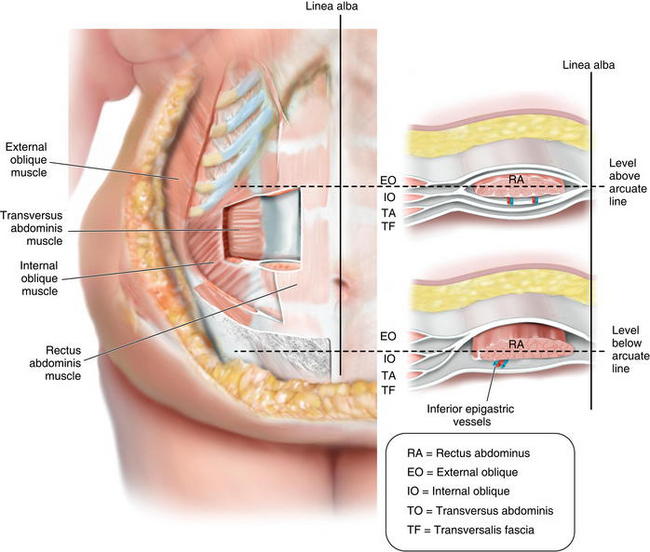

The rectus abdominis and the internal, external, and transverse oblique musculature contribute to the support and contour of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 12-1).

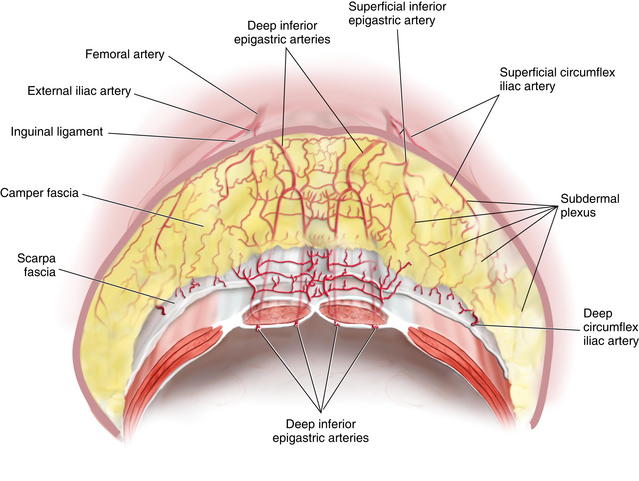

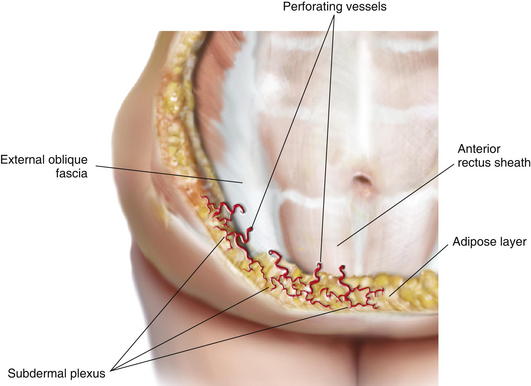

The rectus abdominis and the internal, external, and transverse oblique musculature contribute to the support and contour of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 12-1). The perforating vasculature to the adipocutaneous component of the anterior abdominal wall emanates from the intramuscular vascular network (Fig. 12-2). The majority of significant perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric system. Other blood vessels contributing to the perforating system include the superficial inferior epigastric artery, superficial circumflex iliac artery, and the deep circumflex iliac artery. All of these perforators converge at the dermis, forming the subdermal plexus.

The perforating vasculature to the adipocutaneous component of the anterior abdominal wall emanates from the intramuscular vascular network (Fig. 12-2). The majority of significant perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric system. Other blood vessels contributing to the perforating system include the superficial inferior epigastric artery, superficial circumflex iliac artery, and the deep circumflex iliac artery. All of these perforators converge at the dermis, forming the subdermal plexus. Prior abdominal operations associated with undermining can disrupt this perforating vascular network. However, secondary perforators can evolve over time and may be preserved. In addition, as a compensatory mechanism, the remote vascularity will acclimate to the new perfusion patterns and perfuse the undermined tissue.

Prior abdominal operations associated with undermining can disrupt this perforating vascular network. However, secondary perforators can evolve over time and may be preserved. In addition, as a compensatory mechanism, the remote vascularity will acclimate to the new perfusion patterns and perfuse the undermined tissue.3 Relevant Aponeurotic Anatomy

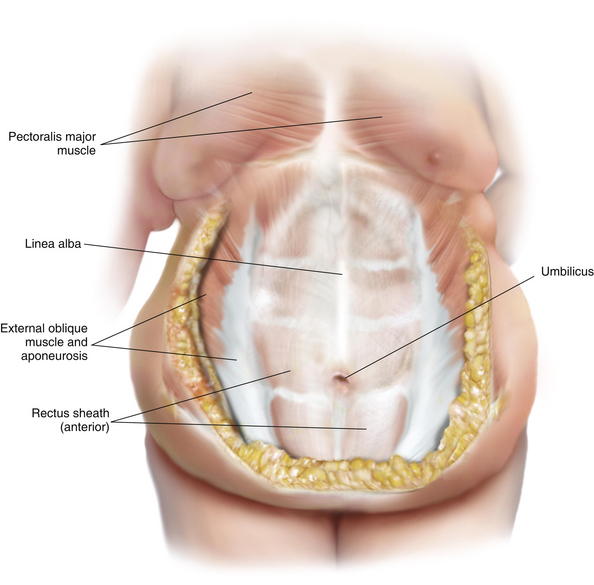

The aponeurotic layers of the anterior abdominal wall include the linea alba, anterior rectus sheath, posterior rectus sheath, and the external oblique fascia (Fig. 12-3).

The aponeurotic layers of the anterior abdominal wall include the linea alba, anterior rectus sheath, posterior rectus sheath, and the external oblique fascia (Fig. 12-3). The anterior rectus sheath and linea alba are composed of collagen fibers arranged in an interwoven lattice. The width and thickness of these structures vary along the surface of the anterior abdominal wall. These measurements fluctuate at various regions of the anterior abdominal wall and are related to the distance from the umbilicus. With respect to the linea alba, its width ranges from 11 to 21 mm between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus and then decreases from 11 to 2 mm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The thickness of the linea alba ranges from 900 to 1200 μm between the xiphoid and the umbilicus and increases from 1700 to 2400 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. With respect to the anterior rectus sheath, the thickness ranges from 370 to 500 μm from the xiphoid to the umbilicus and then increases to 500 to 700 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The posterior rectus sheath, on the other hand, is slightly thicker than the anterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus, ranging from 450 to 600 μm, but then it drops off precipitously from the umbilicus to the arcuate line to 250 to 100 μm.

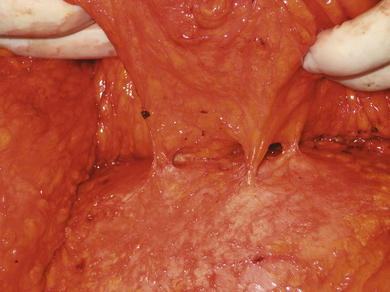

The anterior rectus sheath and linea alba are composed of collagen fibers arranged in an interwoven lattice. The width and thickness of these structures vary along the surface of the anterior abdominal wall. These measurements fluctuate at various regions of the anterior abdominal wall and are related to the distance from the umbilicus. With respect to the linea alba, its width ranges from 11 to 21 mm between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus and then decreases from 11 to 2 mm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The thickness of the linea alba ranges from 900 to 1200 μm between the xiphoid and the umbilicus and increases from 1700 to 2400 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. With respect to the anterior rectus sheath, the thickness ranges from 370 to 500 μm from the xiphoid to the umbilicus and then increases to 500 to 700 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The posterior rectus sheath, on the other hand, is slightly thicker than the anterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus, ranging from 450 to 600 μm, but then it drops off precipitously from the umbilicus to the arcuate line to 250 to 100 μm. Perforating vessels pierce the anterior rectus sheath and external oblique fascia as they course through the adipose layer, until contributing to the subdermal plexus of vessels (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5).

Perforating vessels pierce the anterior rectus sheath and external oblique fascia as they course through the adipose layer, until contributing to the subdermal plexus of vessels (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5).2 Preoperative Considerations

As with all operations, proper patient selection is important. A careful assessment of the risks and benefits of panniculectomy must be made, and the patient must be informed of the risks. These risk factors can increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and complications.

As with all operations, proper patient selection is important. A careful assessment of the risks and benefits of panniculectomy must be made, and the patient must be informed of the risks. These risk factors can increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and complications.1 Preoperative Imaging

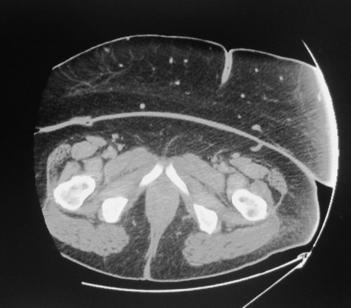

Preoperative imaging is important when considering panniculectomy. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) delineate the size of the hernia defect and provide information regarding the thickness of the abdominal pannus (Fig. 12-6). The abdominal musculature also is appreciated. MRI also permits visualization of the larger arteries and veins that course through the pannus.

Preoperative imaging is important when considering panniculectomy. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) delineate the size of the hernia defect and provide information regarding the thickness of the abdominal pannus (Fig. 12-6). The abdominal musculature also is appreciated. MRI also permits visualization of the larger arteries and veins that course through the pannus.2 Assessment of Risk Factors

Systemic risk factors that require optimization include but are not limited to diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, pulmonary disease, poor nutritional status, cardiac disease, connective tissue disorders, abdominal aortic aneurisms, and immunosuppression. Local risk factors include but are not limited to prior soft tissue or cutaneous infections, fistula, indurated skin, lymphedema, and ulcerations.

Systemic risk factors that require optimization include but are not limited to diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, pulmonary disease, poor nutritional status, cardiac disease, connective tissue disorders, abdominal aortic aneurisms, and immunosuppression. Local risk factors include but are not limited to prior soft tissue or cutaneous infections, fistula, indurated skin, lymphedema, and ulcerations. In patients with an elevated BMI (>35), uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and poor nutritional status, the incidence of complications such as delayed healing, incisional dehiscence, soft tissue necrosis, infection, and prolonged drainage are likely to be increased. The anticipated length of the operation may influence the timing of the panniculectomy, immediate or delayed.

In patients with an elevated BMI (>35), uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and poor nutritional status, the incidence of complications such as delayed healing, incisional dehiscence, soft tissue necrosis, infection, and prolonged drainage are likely to be increased. The anticipated length of the operation may influence the timing of the panniculectomy, immediate or delayed.3 Prior Hernia Surgical History

Prior studies have demonstrated an increased risk of infection in patients with an abdominal hernia. Although, many of these operations appear at first glance to be “clean” operations, they are, in fact, more susceptible to infection. Many of these infections manifest in the skin and subcutaneous fat. The incidence of soft tissue infection is approximately 10-fold higher in patients with a hernia (16% vs. 1.5%). In patients with a prior abdominal hernia repair, the risk of infection continues to increase (42% vs. 12%). Surgeons should be cognizant of these statistics when considering panniculectomy.

Prior studies have demonstrated an increased risk of infection in patients with an abdominal hernia. Although, many of these operations appear at first glance to be “clean” operations, they are, in fact, more susceptible to infection. Many of these infections manifest in the skin and subcutaneous fat. The incidence of soft tissue infection is approximately 10-fold higher in patients with a hernia (16% vs. 1.5%). In patients with a prior abdominal hernia repair, the risk of infection continues to increase (42% vs. 12%). Surgeons should be cognizant of these statistics when considering panniculectomy. In general, prior vertical midline incisions are preferred because a fleur-de-lis pattern can be used. With this pattern, excess skin and fat can be excised in both the horizontal and vertical planes. When the prior incisions are transverse in orientation, problems related to blood supply can occur, especially when the incisions are located in the mid- and upper abdominal areas. Low transverse abdominal incisions are usually fine because this is where the transverse incisions are usually made for panniculectomy.

In general, prior vertical midline incisions are preferred because a fleur-de-lis pattern can be used. With this pattern, excess skin and fat can be excised in both the horizontal and vertical planes. When the prior incisions are transverse in orientation, problems related to blood supply can occur, especially when the incisions are located in the mid- and upper abdominal areas. Low transverse abdominal incisions are usually fine because this is where the transverse incisions are usually made for panniculectomy.