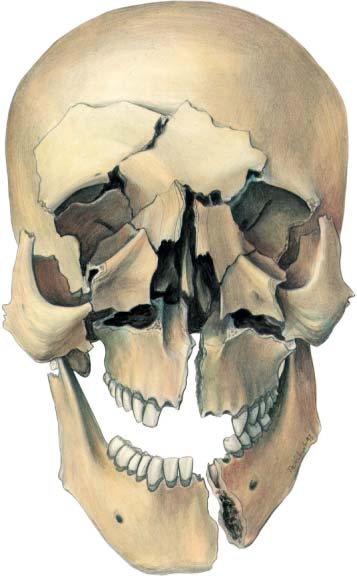

21 Panfacial Fractures: Planning an Organized Treatment In the treatment of panfacial fractures all treatment modalities for single fractures of the craniomaxillofacial area, described in other chapters, come together. A successful outcome of panfacial fracture treatment, however, demands a systematic approach by an experienced team of specialists, working in a trauma center that has all facilities for proper patient care. Developments during the last quarter of the 20th century (such as computed tomography [CT], wide-open reduction, internal fixation, immediate bone grafting, and soft-tissue handling) have revolutionized the potential for restoring the pre-injury appearance and function of panfacial fracture patients. The keys to successful treatment of panfacial trauma remain good exposure, careful reduction and fixation of the fractures. The craniofacial skeleton consists of 22 different bones. These bones surround the different cavities that together form the head. These cavities are the cranium, the orbits, the sinuses, the nose and the mouth. In the craniofacial skeleton, thicker portions of bone are connected to thinner bony walls. These thicker bony structures are called “buttresses” and maintain the craniofacial proportions in height, width and anterior–posterior projection (Fig. 21.1; see also Fig. 1.8). The buttresses form the key to the reconstruction of panfacial fractures and were originally described by Sicher and Tandler (1928), then Merville (1974) and later expanded by Gruss and Mackinnon (1986). Wide exposure of fractures was also advanced by Merville (1974), using the principles of craniofacial surgery transferred to fracture repair. Exposure of the buttresses allows alignment and fixation of the fractures and so provides the potential for anatomical reduction of the bones. Internal fixation with combinations of different sizes of plates and screws provides three-dimensional stability and makes postoperative intermaxillary fixation almost superfluous. (A guide to the use of different plate–screw osteosynthesis systems in the craniofacial area is given in Fig. 21.4.) Highly comminuted bones are replaced by bone grafts. Bone grafting is also used to supplement missing bone or bone volume. However, the need for primary bone grafting is largely reduced because of the stability provided by plate and screw fixation. It is still unclear how long plate–screw fixation provides stability when bridging an area of bone loss. In case of substantial bone loss or gross comminution, bone grafting may still be necessary to guarantee long-term stability (Klotch and Gilliland, 1987). Fig. 21.1 The different buttresses, marked by arrows, that determine the width, height, and projection of the head. These buttresses form the key to the reconstruction of panfacial fractures (see Fig. 1.8). Biting forces produce tension forces (dashed lines) at the upper border and compressive forces (solid line) at the lower border of the mandible. Torsion forces are produced anterior to the canines of the mandible. In this specific sequence a careful history, physical examination, and radiographic evaluation are essential to get a proper understanding of a panfacial injury complex. Whenever possible, information should be gathered about the pre-injury appearance, occlusion, and function. Photographs and dental records can be very helpful. Physical examination should consist of static and dynamic inspection and palpation from chin to crown, in order to identify injuries of the soft tissue, bone, and neurovascular bundles. Special attention should be given to the naso-ethmoid region, the palate, the eye and the condylar process, where injuries are easily overlooked. All patients with severe craniofacial trauma deserve a complete ophthalmological evaluation. CT scanning has replaced most conventional plain radiographs except for those that image the ascending ramus of the mandible, including the condylar process. For initial evaluation, plain radiographs like the Waters view in combination with a submentovertex view and a left and right half mandibular view, described by Eisler, provide valuable overall information. Detailed CT scanning in axial planes provides important information concerning the extent of craniomaxillofacial injuries. Two-dimensional coronal and sagittal reconstructions are most valuable for evaluation of fractures of the orbital walls, maxillary buttresses, and mandibular ascending ramus. The role of three-dimensional imaging is inconclusive. One has to be cautious in evaluating three-dimensional images in areas where the bone is thin or where there is minimal or no displacement. False positive as well as false negative findings are possible. As technology advances, three-dimensional imaging may become of more importance (Fig. 21.2). Currently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) seems of little importance in the initial assessment of a panfacial trauma patient. Fig. 21.2 Panfacial fracture.

Introduction

Diagnosis

Treatment Planning

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree