Patients presenting for revision and reconstructive rhinoplasty demonstrate similar as well as completely different challenges encountered in the primary rhinoplasty patient. Because the nasal soft tissues and skeletal support foundations have been disturbed, removed, or reoriented, unique approaches and procedures must be invoked—but only after a thorough study of the anatomic conditions encountered. The presence and magnitude of inevitable scar tissue development influences planning for the type and magnitude of surgical intervention. Decisions must be made about whether it may be more appropriate and safe to engage in a major dissection and exploration created via the external (open) approach or whether more limited incisions and dissection created through endonasal approaches place the damaged tissues (and therefore the patient) at less risk. It is axiomatic that each successive revisional rhinoplasty procedure may render the anticipated outcome less predictable because of the vagaries of healing of scar tissue. Thus, accurate preoperative diagnosis is vital to correction of the problem in a final restorative procedure. In addition, patients must understand and accept the potential limitations inherent in revision surgery.

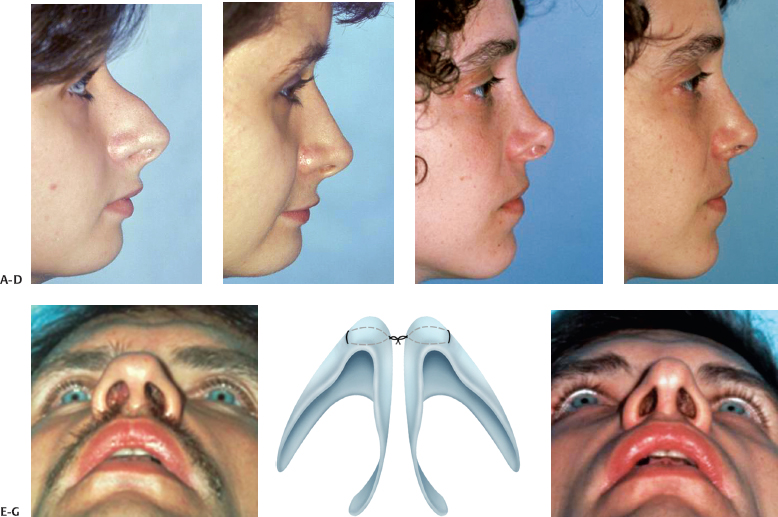

Our 35-year experience validates that revision rhinoplasty patients commonly fall into several categories. Common among secondary cases are those noses in which an incomplete primary operation (Fig. 19–1A) has occurred. The surgeon must accurately diagnose the deficiencies and create a game plan to complete the unfinished procedure. Equally common are those patients in which overaggressive surgery (Fig. 19–1B) has produced deformities, requiring at the very least restoration of supportive structure by grafting and augmenting with appropriate materials to restore balance, function, and harmony. In addition, asymmetrical noses often displease patients and require reoperation. Finally, copious combinations (Fig. 19–1C) of the these surgical shortcomings are encountered, in which attention must be devoted to adding to, subtraction from, and regularizing the previously operated nose to achieve an acceptable outcome.

Guidelines for Revision Rhinoplasty

Guidelines for Revision Rhinoplasty

More than three decades of experience in rhinoplasty have illuminated significant principles and guidelines useful in caring for patients requesting revision surgery.1 This arduous learning curve may be significantly shortened by studying religiously the evolving healing dynamics of the nasal healing process through graphic records coupled with longitudinal standard and uniform photographs over time. Developing the confidence of the revision rhinoplasty patient, often disillusioned and disappointed, supersedes in importance all other requirements.

For surgeons of all levels of experience, the “Ten Commandments in Revision Rhinoplasty” are offered as a helpful beginning guideline (Table 19–1). Clearly, additional principles will occur in individual and unique noses.

- Ensure that improvement is possible. It is always tempting to attempt to revise every nasal deformity, no matter how difficult or problematic. Not all rhinoplasty deformities can be satisfactorily corrected; some, in fact may be made worse by surgical intervention. We attempt to make that point very clear to patients contemplating surgery, advising that not all deformities can be corrected. We require each patient to “rank order” the deformities that exist in order of importance, in case not every abnormality may be corrected.

- Make an accurate diagnosis. This principle is essential for ensuring commandment #1. Palpation of the suppleness, mobility, and scarring of the skin-subcutaneous tissue complex is equally important to visual inspection of the topography and internal airway of the nose. Determining which anatomic components of the nose require repair—equally importantly which do not—is vital. Determinations must be made about which regions of the nose require addition reduction and which require supplemental augmentation.2 In deviated noses, the elements creating the deviation must be clearly identified before effective repair is possible. The presence or absence of residual septal cartilage, confirmed by palpation and transillumination, provides a guideline to the alternative of auricular cartilage use for aspects of repair. Of greatest importance in the initial analytic process is the psychological determination of whether the patient’s expectations can be realized. If the surgeon opts to undertake revision surgery, it must be with the realization that the patient, and all the previous surgical outcomes, now become his or hers.

- Instill realistic patient expectations. The overarching goal of every rhinoplasty, primary or secondary, is to make the patient happy. Because of differences in experience as well as aesthetic preferences, the surgeon and patient may harbor entirely different expectations about revisional surgery. It is helpful, perhaps even mandatory, to place the patient in front of a three-way mirror and require a detailed description of what is disliked and what is expected (see Fig. 19–2). Nowhere in aesthetic facial surgery is true, informed consent more important. Limitations of reparative surgery must be stressed, with acceptance by the patient being the passport to undertaking surgical corrective attempts.

- Consider surgical timing carefully. Surgical textbooks commonly recommend a delay of at least 1 year before contemplating revision rhinoplasty. It is true that at least this period of time must elapse before scar tissue is sufficiently mature to withstand additional repair without worsening the complication. Depending on the amount and degree of trauma created by the first (or subsequent) operations, a delay of more than 1 year may be necessary to ensure safety and predictable healing. Exceptions to this temporal principle exist and, properly diagnosed and understood, will allow revision much sooner than 1 year and promote earlier patient satisfaction without undue risk. An inadequate or lateralized greenstick osteotomy may be safely and effectively infractured early on after detection. Alar base reduction, deferred or not considered at the primary operation, does not require months of healing to be carried for ultimate improved refinement of nasal proportion. Correction of alar sidewall collapse may be performed at any point in the postoperative period, using a convex auriculary cartilage batten. Likewise, cephalic alar retraction in the early postoperative period may be safely corrected with composite auricular grafts. Rasping of an asymmetry or small deformity of the bony dorsum (facilitated with the minimally traumatic mechanical rasp or bur) is generally safe and effective within several months after primary rhinoplasty. Augmentation rhinoplasty soon after removal of an extruding silicone or silastic implant, when the wound is clean and infection free, is generally safely employed. Other modest corrective procedures, if they involve minimal and limited tissue dissection, may be logically contemplated. All major surgical revisions, particularly those requiring structural grafting via an open approach, should be delayed until the tissues are pliable, scar tissue is supple and mature, and few further healing changes are anticipated.

- Diagnose and correct functional problems first. A common indication for revision surgery is failure to correct nasal obstruction from septal deviation or deformity. Thorough rhinoscopy after intense shrinkage of the nasal mucosa should reveal the majority of obstructive problems. Also necessary may be correction of nasal valve collapse, turbinate hypertrophy, alar collapse after overreduction of the alar cartilages, and overnarrowing of the nasal bony pyramid.

- Plan reconstruction options and alternatives. Unlike primary rhinoplasty, in which studious inspection and palpation reveals for the experienced surgeon a clear understanding of the surgical needs, revision rhinoplasty not uncommonly leads to surprises on entering the nose. Subcutaneous scar tissue often imparts unpredictable contours to the external cutaneous topography, which may change significantly when undermining of the soft tissue sleeve is undertaken. Dense scar likewise hinders accurate palpation of the skeletal support of the nasal tip. During revision rhinoplasty, the surgeon must remain flexible as the dynamics of the operation unfold differently than might have been expected. In particular, plans for grafting with cartilaginous or soft tissue autografts are essential in the majority of secondary procedures.3 Surgical improvisation, based on sound experience and good surgical judgment, requires that the successful revision rhinoplasty surgeon possess mastery of a wide variety of reconstruction techniques to manage the myriad number of complications possible after rhinoplasty.

- Limit surgical dissection whenever possible. The blood supply of the scarred nose is tenuous and unpredictable; extensive dissection and undermining involves increasing risk of poor healing and further damage to and thinning of the overlying skin–subcutaneous canopy. Surface irregularities may develop after even modest undermining of an attenuated skin–subcutaneous canopy. In the majority of reconstructive revision rhinoplasties, it is judicious to limit dissection of nasal tissues to the minimum possible to gain exposure. Less additional scar is produced, unpredictable healing is minimized, and the visual results of tissue grafting are readily and more quickly apparent. If dissection in several regions of the nose is required, we prefer to create several different precise tissue pockets, through limited incisions, to gain access to the nose for either reduction or augmentation surgery. The exposure provided by the external rhinoplasty approach is unparalleled and provides the surgeon with the benefit of direct open visualization of tissue defects and the enhanced ability to suture-fixate grafts. We reserve this approach, requiring extensive tissue dissection, for those revision patients requiring exploration for unexplained deformities, severe distortion of the nasal tip, middle vault deformities requiring grafting, and, whenever necessary, grafts requiring suture-fixation for long-term stabilization.

- Implant autogenous tissue only. The previously operated nose, especially if blood supply is compromised and the skin-subcutaneous complex is damaged, scarred, or attenuated, supports all forms of alloplastic implants poorly. Respected surgeons worldwide are near unanimous in their preference for autogenous tissue implant reconstruction in secondary rhinoplasty. We prefer autogenous cartilage (septal, auricular, rib), bone, fascia (temporalis, facial subcutaneous musculo-aponeurotic system [SMAS], fascia lata), dermis, perichondrium, and occasionally mature scar (if available) for nasal reconstruction. Vitally, the young patient undergoing revision rhinoplasty, with a life expectancy of 60 to 70 years, deserves the demonstrated long-term safety of autogenous materials. In the near future, biogenetic engineering will undoubtedly supply unlimited quantities of cloned nonimmunogenic cartilage for effective and safe reconstruction of damaged noses.

- Maximize concepts of “illusion” in revision surgery. In many secondary rhinoplasties, chosen with care, elegant refinement can be created by fashioning visual illusions, by changing nasal proportions, or by grafting. Difficult deviated noses may be “straightened” by carefully designed cartilage grafts on or along the nasal dorsum. The overrotated nose may be visually “lengthened” by dorsal onlay grafting combined with cartilage grafts to the infratip lobule. Recessing the dependent “hanging” columella may render an apparently overlong nose proportionate. Wise surgeons recognize that not every revision patient requires a “complete” secondary rhinoplasty; improvement is often best achieved with more conservative but equally effective surgery—with less risk.

- Avoid irreparable deformities. Every revision rhinoplasty surgeon will encounter patients with deformities of such a serious nature that no amount of surgical skill or ingenuity can hope to provide satisfactory correction. Although often difficult, it is always judicious to gently refuse to operate on such patients and to disengage, because the outcome may be unsatisfactory to the patient and surgeon alike. The classic example is the “VIP” patient, often multiply operated, who seeks corrective efforts that are clearly unrealistic or not surgically possible. The seductive nature of playing to the ego of the surgeon must be recognized and forestalled.

|

Rhinoplasty Complications

Rhinoplasty Complications

Although the satisfaction level of primary rhinoplasty patients remains at a high level, inadequate or unanticipated outcomes do occur. The increasing worldwide employment of the open approach is actually spawning complications that involve a higher degree of difficulty to repair, as less experienced surgeons undertake complicated problems that are falsely assumed to be easier using the open approach.

A frequently quoted aphorism in rhinoplasty states: “if you do enough surgery, you’ll see every complication in the book. …” Although perhaps dramatic and memorable, this bold statement is clearly in error and requires refutation. Complications do occur in rhinoplasty surgery, as in any surgical endeavor in which little tolerance for error exists and exacting surgery must prevail. However, with accurate diagnosis, planning, and execution, rhinoplasty complications experienced by thoughtful surgeons are clearly infrequent, minimal, and correctable by additional minor surgery.1 Major complications rarely occur in this operation when attention to detail is rigid and exacting.

In this discussion, we examine typical and common complications that do occur during and after nasal plastic surgery, focusing on those that most commonly present to the revision rhinoplasty surgeon (Table 19–2). To the extent possible, the root causes and prevention of these problems will be examined, in an effort to limit future complications by an understanding of the complex dynamics existing during the interrelated steps performed in rhinoplasty. Time-tested surgical solutions to many of these problems, based entirely on the variant anatomy encountered, will be suggested to the surgeon encountering patients presenting for potential revision surgery. Prevention of complications remains a paramount goal in all of aesthetic surgery. Except where functional impairment has created discomfort or disease, patients seeking rhinoplasty are essentially well patients whom the surgeon has the opportunity to make sick (or at least unwell).

| Tip | Columella |

| Bossa | Overwide |

| Asymmetry | Overnarrow |

| Overprojection | Twisted |

| Underprojection | Deviated |

| Pinched | Depression (crevice) |

| Wide (boxy) | Short |

| Bifid | Elongated |

| Deviated | Collapsed |

| Ptotic | Visible strut |

| Dependent | Overlong strut |

| Overrotated | Foreign body |

| Twisted | Overwide pedestal |

| Crucified | Asymmetry |

| “Shrink wrapped” | Scarred |

| Asymmetric medial crural | |

| footplates | |

| Bony Pyramid | Dependent |

| Irregularity | Retracted (hidden) |

| Overreduction | Webbed |

| Underreduction | Overconvex |

| Asymmetry | Poor contour |

| Overwide | Obtuse nasolabial angle |

| Overnarrow | Acute nasolabial angle |

| “Open roof” | |

| Shallow nasofrontal angle | Alar Lobule |

| Overdeep nasofrontal angle | Retracted alar margin |

| Dependent alar margin (hooding) | |

| Cartilaginous Pyramid | Asymmetric lobules |

| Overreduction (saddling) | Notching |

| Underreduction (pollybeaks) | Alar Base |

| Irregularities | Overwide alar base |

| Prominent anterior | Overnarrow alar base |

| septal angle | Asymmetric alar base (nostrils) |

| Deviation | Visible alar base scars |

| Twisted | |

| “Inverted V” deformity | Alar Lobule |

| Middle vault collapse (unilateral, bilateral) | Retracted alar margin Dependent alar margin (hooding) |

| Asymmetric lobules | |

| Asymmetries | Notching |

| Overnarrow | |

| Overwide | Uncommon and Rare |

| “Shrink wrapped” | Complications |

| Foreign bodies | Bleeding |

| Soft tissue excess | Infection |

| Hyposmia | |

| Transient septic shock | |

| Psychological Complication | syndrome |

| Anesthetic medication reactions | |

| Patient dissatisfaction | Psychotic breakdown |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | |

| Pneumocephalus | |

| Lacrimal drainage apparatus injury |

Clear distinctions must be drawn between complications and sequelae after rhinoplasty. True complications consist of untoward, unforeseen, and unwanted problems after surgery, many of which demand additional treatment in the early or late period after surgery. These are largely preventable and avoidable. Sequelae of rhinoplasty (e.g., scarring from internal and external nasal incisions, obliteration of normal tissue planes, alteration of skin thickness and elasticity) occur in every procedure and do not fall into the category of complications: they are expected, predictable, essentially controllable, and require no further surgical intervention. Patients and surgeons alike must be able to clearly distinguish between these two important categories.

What to the patient appears to be a complication in the early postoperative period (supratip swelling, hardness of the tip, thickened skin-subcutaneous tissue envelope) constitutes essentially the sequelae of early healing. It is often the surgeon’s responsibility to skillfully mollify the patient while favorable events in the continuing healing process unfold over time, improving the overall appearance of the nose. This process is best engaged in and initiated before surgery, so that patients expect and anticipate a reasonable healing period to improve their appearance. A useful aphorism in facial plastic surgery applies here: “information given before surgery creates enlightenment; information after surgery is simply an excuse.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree