Chapter 7 Open Repair of Parastomal Hernias ![]()

2 Clinical Anatomy

1 Dissection Planes

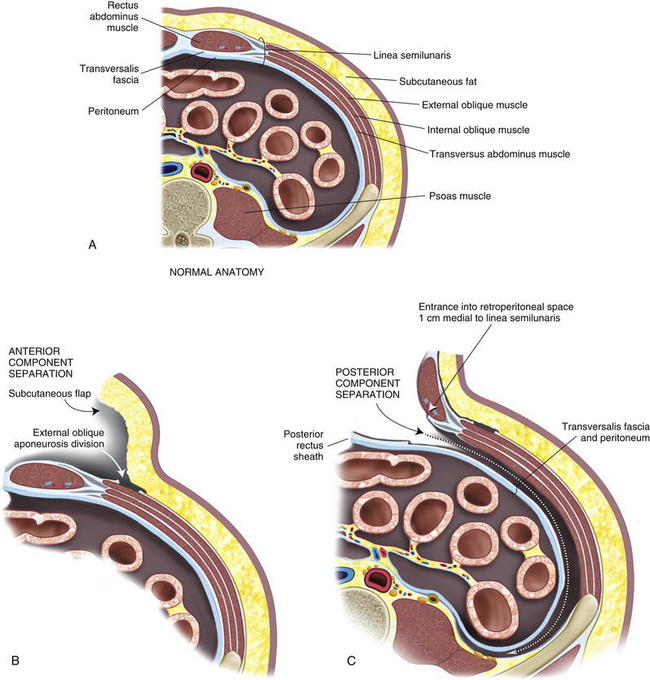

Abdominal wall anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 1. It is essential to understand the anatomic layering of the abdominal wall for proper retrorectus/retroperitoneal mesh placement and anterior component separation.

Abdominal wall anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 1. It is essential to understand the anatomic layering of the abdominal wall for proper retrorectus/retroperitoneal mesh placement and anterior component separation. The linea semilunaris lies at the lateral aspect of the posterior rectus sheath. Rectus innervation is preserved and plane development is facilitated by entrance into the retroperitoneal space medial to the linea semilunaris. Dissection in the retroperitoneal space is below the transversus abdominis muscle and can be completed to the psoas. Mesh placement is in this retroperitoneal space.

The linea semilunaris lies at the lateral aspect of the posterior rectus sheath. Rectus innervation is preserved and plane development is facilitated by entrance into the retroperitoneal space medial to the linea semilunaris. Dissection in the retroperitoneal space is below the transversus abdominis muscle and can be completed to the psoas. Mesh placement is in this retroperitoneal space. Anterior component separation involves division of the external oblique aponeurosis lateral to the rectus sheath. Access for this division can be achieved via subcutaneous flap or via laparoscopic techniques as described previously (see Chapters 8 and 11) (Fig. 7-1).

Anterior component separation involves division of the external oblique aponeurosis lateral to the rectus sheath. Access for this division can be achieved via subcutaneous flap or via laparoscopic techniques as described previously (see Chapters 8 and 11) (Fig. 7-1).2 Ostomy Site Selection

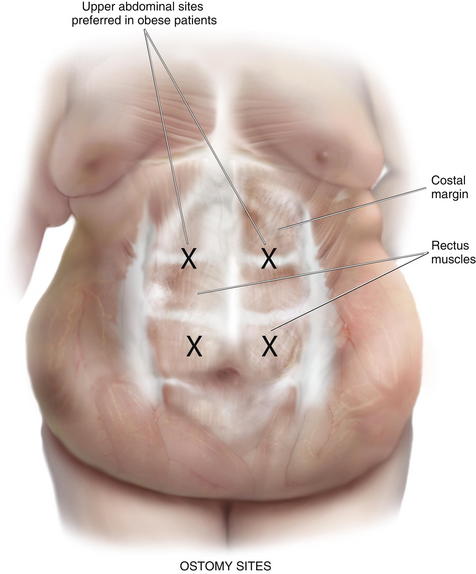

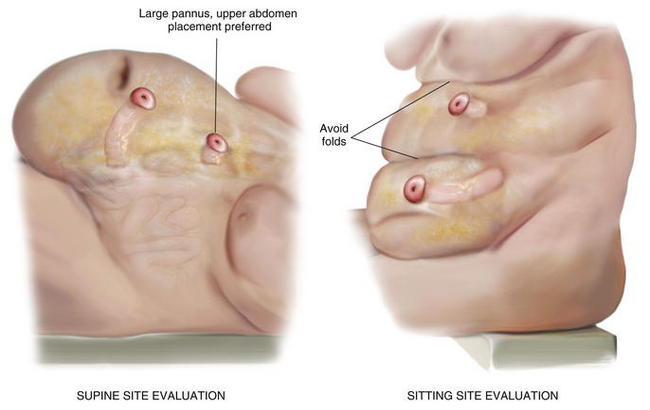

Ostomy sites are chosen with the assistance of an enterostomal therapist and are marked preoperatively. Patients should be examined while sitting and supine, and an appropriate location visible to the patient is found. Transrectus placement is typically preferred. Folds should be avoided to facilitate appliance adhesion. Thus, it is essential to examine the patient while he or she is sitting in order to visualize folds. Obese patients with a significant pannus should be sited in the upper abdomen. During complex abdominal wall reconstruction, excess skin and subcutaneous tissues are often resected, and therefore consideration must be given to the eventual placement of the stoma (Figs. 7-2 and 7-3).

Ostomy sites are chosen with the assistance of an enterostomal therapist and are marked preoperatively. Patients should be examined while sitting and supine, and an appropriate location visible to the patient is found. Transrectus placement is typically preferred. Folds should be avoided to facilitate appliance adhesion. Thus, it is essential to examine the patient while he or she is sitting in order to visualize folds. Obese patients with a significant pannus should be sited in the upper abdomen. During complex abdominal wall reconstruction, excess skin and subcutaneous tissues are often resected, and therefore consideration must be given to the eventual placement of the stoma (Figs. 7-2 and 7-3).3 Preoperative Considerations

1 Comorbidities

Appropriate patient selection and optimization is essential. The procedure results in a significant physiologic insult. An extended operation with a long midline incision and prolonged adhesiolysis is typical. Significant fluid shifts should be expected. Those with extensive cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease should be vetted carefully and optimized maximally. Risk of surgery may be prohibitive in some.

Appropriate patient selection and optimization is essential. The procedure results in a significant physiologic insult. An extended operation with a long midline incision and prolonged adhesiolysis is typical. Significant fluid shifts should be expected. Those with extensive cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease should be vetted carefully and optimized maximally. Risk of surgery may be prohibitive in some. Combined ventral and parastomal hernias are typical. With large hernias there may be significant loss of abdominal domain. Intraabdominal reduction results in increased abdominal compartment pressures with potential for pulmonary and renal compromise. The use of a large biologic mesh prosthesis partially mitigates this problem; however, perioperative intensive care including brief ventilator support is not unusual.

Combined ventral and parastomal hernias are typical. With large hernias there may be significant loss of abdominal domain. Intraabdominal reduction results in increased abdominal compartment pressures with potential for pulmonary and renal compromise. The use of a large biologic mesh prosthesis partially mitigates this problem; however, perioperative intensive care including brief ventilator support is not unusual. Timing of the operation is important as well. An appropriate interval from previous surgeries should be allowed. This typically should be a minimum of 3 months. However, with a history of a significant inflammatory process or hostile abdomen on previous exploration, a longer interval (6 months to a year) may be appropriate. On exam before exploration, ideally, the abdominal skin overlying any midline hernia should be mobile and soft without significant adherence to underlying bowel loops.

Timing of the operation is important as well. An appropriate interval from previous surgeries should be allowed. This typically should be a minimum of 3 months. However, with a history of a significant inflammatory process or hostile abdomen on previous exploration, a longer interval (6 months to a year) may be appropriate. On exam before exploration, ideally, the abdominal skin overlying any midline hernia should be mobile and soft without significant adherence to underlying bowel loops. Those that present with infected prosthetic mesh with or without fistulas are particularly good candidates for this approach. The duration and complexity of operation can be expected to increase significantly in this situation.

Those that present with infected prosthetic mesh with or without fistulas are particularly good candidates for this approach. The duration and complexity of operation can be expected to increase significantly in this situation. Preoperative imaging with abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans is routinely performed. These images provide important information as to the exact location of the stoma in the abdominal wall, the integrity of the rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature, and the size of the parastomal and midline hernias. In addition, the surgeon can be alerted to possible loss of abdominal domain and plan appropriately.

Preoperative imaging with abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans is routinely performed. These images provide important information as to the exact location of the stoma in the abdominal wall, the integrity of the rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature, and the size of the parastomal and midline hernias. In addition, the surgeon can be alerted to possible loss of abdominal domain and plan appropriately.2 Two-Team Approach

We have found a two-team approach particularly efficacious. One team focuses on adhesiolysis, intestinal mobilization, resection, and repair as appropriate. A second team proceeds with abdominal wall reconstruction. In our institution, we typically use a colorectal surgical team and a general surgical team. Although, one surgeon can certainly accomplish these procedures, fatigue of the operating team does become a factor with operative times averaging about 5 hours. A planned two-team approach helps facilitate procedure progression in these prolonged cases.

We have found a two-team approach particularly efficacious. One team focuses on adhesiolysis, intestinal mobilization, resection, and repair as appropriate. A second team proceeds with abdominal wall reconstruction. In our institution, we typically use a colorectal surgical team and a general surgical team. Although, one surgeon can certainly accomplish these procedures, fatigue of the operating team does become a factor with operative times averaging about 5 hours. A planned two-team approach helps facilitate procedure progression in these prolonged cases.3 Operative Options

Multiple methods of parastomal hernia repair, both laparoscopic and open, have been described. The multiplicity of procedures belies the complex nature of the problem and the lack of a clear and simple, yet efficacious repair.

Multiple methods of parastomal hernia repair, both laparoscopic and open, have been described. The multiplicity of procedures belies the complex nature of the problem and the lack of a clear and simple, yet efficacious repair. Direct suture repair has been frequently described but has an unacceptably high recurrence rate. Mesh, either biologic or synthetic, placed in a subcutaneous overlay, or in a retrorectus underlay has been described with variable results. Stomal transposition with or without mesh use has been used also, and results have also been variable.

Direct suture repair has been frequently described but has an unacceptably high recurrence rate. Mesh, either biologic or synthetic, placed in a subcutaneous overlay, or in a retrorectus underlay has been described with variable results. Stomal transposition with or without mesh use has been used also, and results have also been variable.