, Madan Ethunandan2 and Tian Ee Seah3

(1)

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Poole, Dorset, UK

(2)

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Southampton NHS Trust Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK

(3)

Orange Aesthetics and Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, Singapore, Singapore

Subunits and Anatomical Considerations

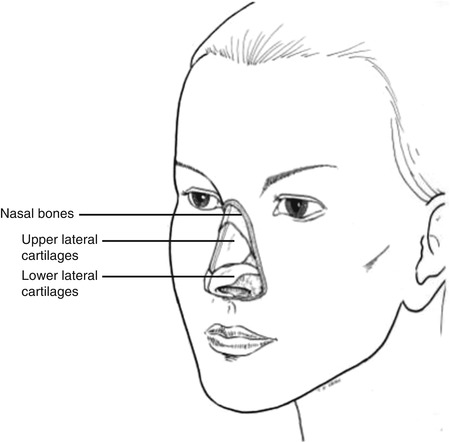

The nose is a complex structure and lends itself to being further divided into subunits, separated by less discrete borders. It is typically divided into nine subunits: columella, tip, dorsum and paired sidewalls, ala and nasal facets (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1

Nasal subunits

The complex three-dimensional shape is supported by a bony and cartilaginous framework. The overlying skin is of varying thickness and mobility and the deep surface is lined by mucous membrane. It is thick and less mobile caudally around the tip and ala and thinner and more mobile in the cephalic region along the dorsum and sidewalls. The nasal bones, upper lateral and septal cartilage provided support to the dorsum and sidewalls and the lower lateral cartilage to the ala. The tip and columella are supported by the septal and lower lateral cartilages (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2

Supporting framework of the nose

The concept of “subunit” reconstruction was initially popularised for the nose and often involves altering the size and shape of the defect to reconstruct a full subunit, if the defect involves more than half the subunit, so that the scars lie in the most advantageous positions and deceive the eye. Adequate cartilage and skeletal support should be provided to support the reconstruction. The ala contains the lower lateral cartilage in its medial/superior aspect and only fibrofatty tissue in its lateral/inferior aspect. Cartilage support may be required for reconstruction of the alar subunit to prevent collapse, even if the defect only involves the lateral aspect.

Nasal Dorsum Defects

Primary Closure (Vertical)

Indications

Small defect

Technique

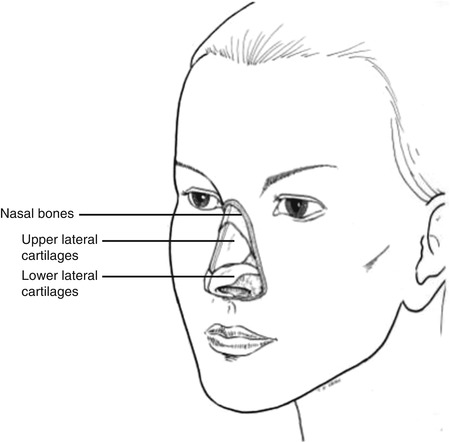

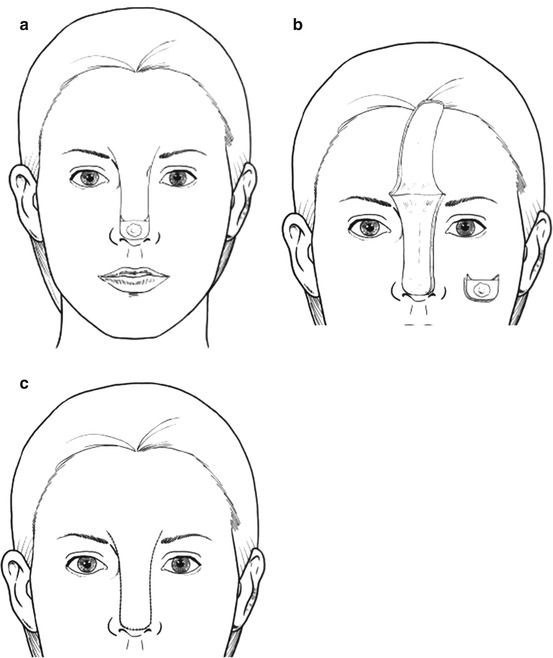

The defect is converted into an ellipse to lie along the vertical glabellar RSTLs. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane superiorly and in the sub-muscular plane in the mid-/lower dorsum. The wound edges are mobilised and closed in layers (Fig. 7.3a–c).

Tips

Determine tissue laxity prior to procedure, if considering closure of mid-/lower dorsum defects. Closure of larger upper defects can “medialise” the eyebrows and needs to be taken into account and discussed with the patient.

Fig. 7.3

Primary closure – Vertical

Primary Closure (Horizontal)

Indications

Small defect

Technique

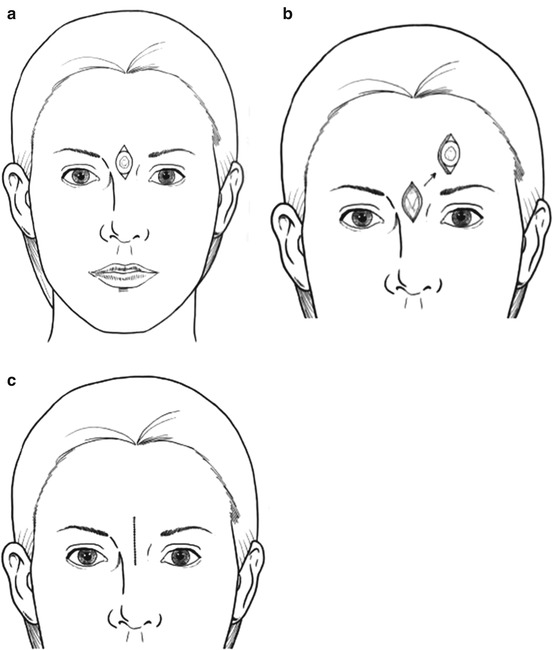

The defect is converted into an ellipse to lie along a horizontal skin crease. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane superiorly and in the sub-muscular plane in the mid- and lower dorsum. The wound edges are mobilised and closed in layers (Fig. 7.4a, b).

Tips

Determine tissue laxity prior to procedure, if considering closure of mid-/lower dorsum defects. Closure of larger defects can alter the position of the nasal tip, which can be advantageous in some circumstances.

Fig. 7.4

Primary closure – Horizontal

Glabellar Advancement Flap

Indications

Medium defect, mid-/lower dorsum and nasal tip

Technique

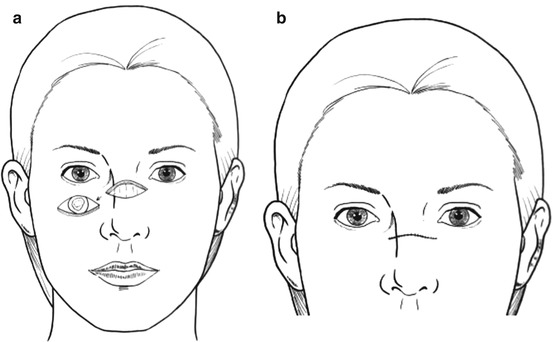

The defect is “squared off” to have parallel edges. Two incisions are made from the superior margins of the defect, along the junction of the dorsum and sidewalls, up to and if necessary just past the glabella. The flap is raised in the sub-muscular plane. The surrounding wound edges are undermined and closed in layers (Fig. 7.5a–c).

Tips

Skin laxity in the glabella and nasal dorsum should be determined prior to utilising this flap. A flap length of up to three times the size of the defect can be raised, but it is mandatory to avoid tension on closure. A flap of inadequate length can lead to an unsatisfactory up turned nasal tip, though in the elderly the tip elevation might be advantageous. The advancing edge of the flap should be fashioned to lie along the junctions of the subunits for maximum scar camouflage.

It is important to anchor the deep surface of the flap to the underlying tissues at the root of the nose to prevent “tenting”. The difference in the length of the wound margins can be accommodated by differential suturing, and Burow’s triangles are best excised in the glabellar skin creases.

Fig. 7.5

Glabellar advancement flap

Glabellar Transposition Flap

Indications

Medium defect mid-/lower dorsum

Technique

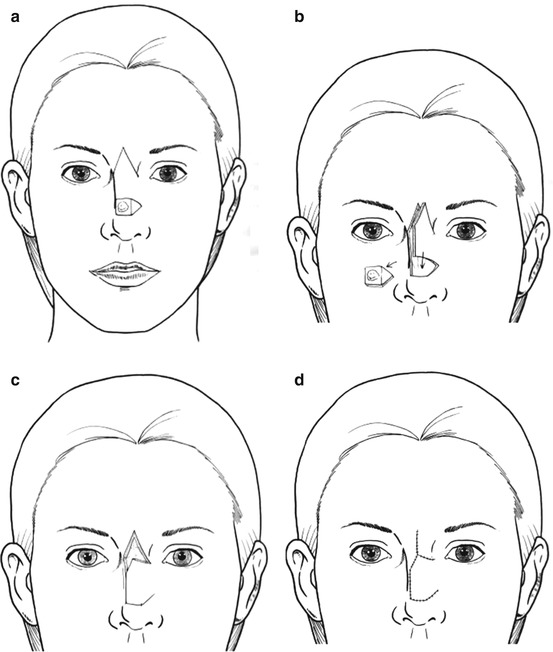

The defect is modified into a triangle with a horizontal long axis. A curvilinear incision is made from the superior edge of the defect, along the junction between the cheek and the nasal sidewall. It is extended superiorly into the glabellar skin crease, passing about 0.5 cm away from the medial canthus. A back cut is made from the summit, across to the contralateral medial canthus. The nasal component of the flap is raised in the sub-muscular plane and the glabellar component in the subcutaneous plane. The wound margins are widely undermined and closed in layers. The secondary glabellar/nasal root defect is closed primarily and any excess skin in the superior aspect of the flap discarded. Dog-ear at the primary defect is corrected as required (Fig. 7.6a–d).

Tips

In case of smaller/midline defects, the superior curvilinear incision can be made at the junction of the nasal dorsum and sidewall. The flap might require thinning along the caudal margin and medial canthus region for better inset. A flap of inadequate mobility can lead to an unsatisfactory upward displacement of nasal tip, though in the elderly this might be advantageous. Primary closure of the glabellar defect medialises the eyebrows and would have to be taken into account, when considering this flap.

Fig. 7.6

Glabellar transposition flap

Nasal Tip Defects

Primary Closure

Indications

Small defect

Technique

The defect is modified into a vertical ellipse. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and closed in layers.

Tips

Useful in the elderly and those with bulbous tips. Larger defects closed primarily lead to displacement of the nasal tip and alar margins.

Skin Graft

Indications

Medium/large defects

Technique

The defect is enlarged to encompass the whole nasal tip subunit, if the initial defect involves more than half the subunit. An accurate template is made of the final defect, which is transferred to the donor site to harvest a full-thickness skin graft. The “defatted” graft is sutured to the defect, with additional “long” sutures that can be used for “tying” over the bolus. The graft can be “quilted” to the base, to decrease the risk of haematoma and dead space. A non-adherent dressing is laid over the sutured graft, over which a cotton wool ball/sponge soaked in proflavin or a suitable antibiotic ointment is placed. The tie-over bolus sutures are now used to hold the dressing in place. The sutures and pack are removed in 7–10 days time (Fig. 7.7a–e).

Tips

A more acceptable result is obtained in individuals with thin skin and superficial defects.

Fig. 7.7

Skin graft

Sidewall Defects

Primary Closure

Indications

Small defect

Technique

The defect is modified into a vertical ellipse. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and closed in layers.