6 Non-ablative fractional laser rejuvenation

Summary and Key Features

• Non-ablative fractional resurfacing is a safe and effective treatment that has become the cornerstone for facial rejuvenation and acne scarring

• It is effective in treating a variety of conditions including acne scarring, mild to moderate photoaging, and some forms of dyspigmentation

• Non-ablative fractional photothermolysis (NAFR) has minimal downtime with almost no restrictions on activity immediately following treatment

• Common areas treated include the face, neck, chest, and hands

• All Fitzpatrick skin phototypes can be treated provided settings are adjusted accordingly

• The preoperative consultation is a vital component of the treatment regimen to ensure optimal outcomes

• Erythema and edema are common sequelae after treatment and resolve within a few days

• Long-term complications are exceedingly rare

• Technology in the field is changing rapidly and the selection of equipment is based on individual preference

• Home-based devices are a new frontier for lasers but will not replace office-based systems

Pathophysiology

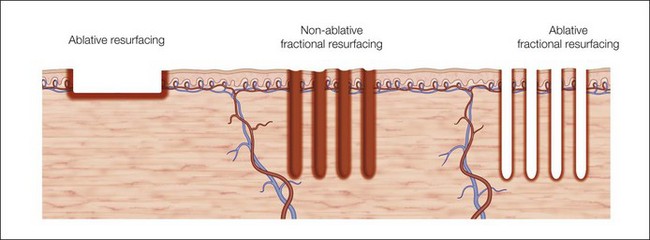

In fractional photothermolysis, a regular array of pixelated light energy creates focal areas of epidermal and dermal tissue damage or microthermal treatment zones (MTZ) (Fig. 6.1). Since its inception, several different lasers have been developed to take advantage of this technological advance. Each laser has parameters that can modify the density, depth, and size of the vertical columns of MTZs. The individual wounds created by FP are surrounded by healthy tissue resulting in a much quicker healing process when compared with traditional ablative skin resurfacing. This targeted damage with MTZ is hypothesized to stimulate neocollagenesis and collagen remodeling leading to the clinical improvements seen in scarring and photoaging. In the original study by Manstein et al., the histologic changes seen after NAFR were elegantly described. Immediately following treatment, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) viability staining showed both epidermal and dermal cell necrosis within a sharply defined column correlating with the MTZ. There was continued loss of dermal cell viability 24 hours after treatment, but via a mechanism of keratinocyte migration, the epidermal defect had been repaired. One week after treatment, individual MTZs were still evident by LDH staining, but after 3 months there was no histologic evidence of loss of cell viability. Water serves as the target chromophore allowing for thermal damage to epidermal keratinocytes and collagen.

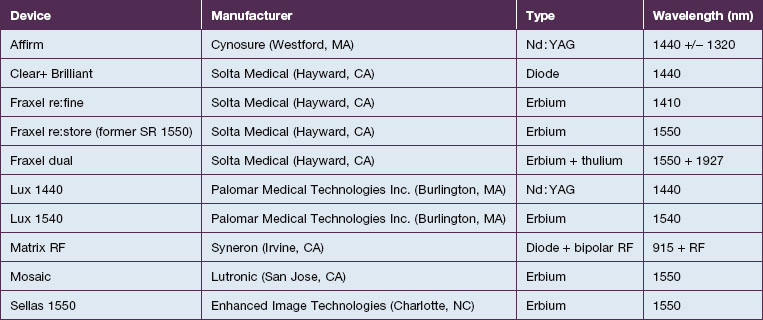

Equipment

As the technology of fractional photothermolysis continues to evolve, new devices continually come to market. A list of currently available NAFR systems is given in Table 6.1. The table is not comprehensive and, as one can imagine, the devices will change constantly. This section will provide a brief description of a few of the more commonly used devices.

Applications

While NAFR is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of benign epidermal pigmented lesions, periorbital rhytides, skin resurfacing, melasma, acne and surgical scars, actinic keratoses, and striae, it has been reported to be used in many other clinical settings (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1

Clinical indications for non-ablative fractional resurfacing

Photoaging

With their seminal study in 2004 using a prototype non-ablative fractional resurfacing device, Manstein and colleagues first demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of fractional photothermolysis by showing improvement in periorbital rhytides. Three months after four treatments with the fractionated device, 34% of patients had moderate to significant improvements and 47% had improvement in texture as rated by blinded investigators. Overall, 96% were noted to be ‘better’ post-treatment. The skin tightening seen after non-ablative fractional resurfacing is similar to ablative resurfacing with tightening within the first week after treatment, apparent relaxation at 1 month, and retightening at 3 months (Case study 1).

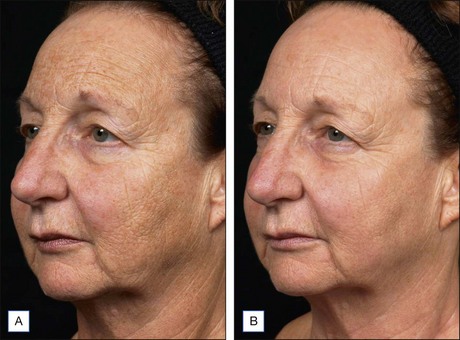

Subsequent reports have confirmed the efficacy of NAFR beyond just periorbital lines. Wanner and colleagues showed statistically significant improvement in photodamage of both facial and non-facial sites with 73% of patients improving at least 50%. In 2006, Geronemus also reported his experience with fractional photothermolysis, finding it to be effective in treating mild to moderate rhytides. Figures 6.2 and 6.3 show typical improvement in rhytides and pigmentation after treatment with non-ablative fractional resurfacing. For deeper rhytides, such as the vertical lines of the upper lip, improvement is also seen but not nearly to the same degree as in ablative approaches.

Figure 6.2 Improvement in moderate rhytides 1 month after two treatments with Fraxel 1927 nm.

(Photo courtesy of Solta Medical.)

Figure 6.3 Improvement in rhytides and dyspigmentation 1 month after three treatments with Fraxel re:store.

(Photo courtesy of Solta Medical.)

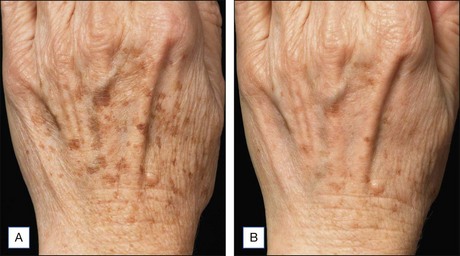

NAFR is also considered to be an effective and safe treatment modality for photoaging off the face including the neck, chest, arms, hands (Fig. 6.4), legs, and feet. These body sites are typically very challenging to treat with other treatment modalities given either increased risks of complications (e.g. scarring) associated with ablative technologies or lack of efficacy that has been previously observed with other non-ablative devices. Jih et al reported statistically significant improvement in pigmentation, roughness, and wrinkling of the hands in ten patients treated with non-ablative fractional resurfacing. In our experience, we have found NAFR to be very safe when settings are adjusted accordingly.

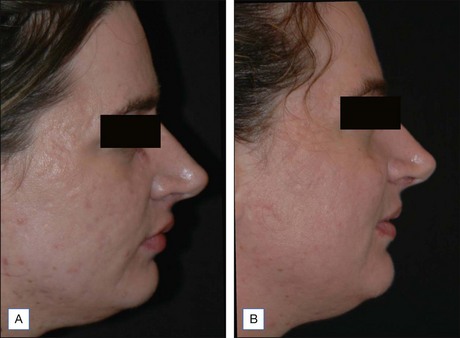

Scarring

Scarring can induce a tremendous psychological, physical, and cosmetic impact on individuals. Previous therapeutic modalities in scar treatment include surgical punch grafting, subcision, dermabrasion, chemical peeling, dermal fillers, as well as laser resurfacing with ablative and non-ablative devices. Published studies have demonstrated that NAFR can be successfully utilized in the treatment of various forms of scarring, including acne scarring, with a very favorable safety profile (Fig. 6.5). Mechanistically, fractional photothermolysis allows controlled amounts of high energy to be delivered deep within the dermis resulting in collagenolysis and neocollagenesis, which smoothes the textural abnormalities of acne scarring. In a large clinical study, Weiss showed a median 50–75% improvement of acne scars using a 1540 nm fractionated laser system after three treatments at 4-week intervals with 85% of patients rating their skin as improved. Alster showed similarly impressive results in a study of 53 patients with mild to moderate acne scarring; 87% of patients who received three treatments at 4-week intervals showed at least 51–75% improvement in the appearance of their acne scars. Non-ablative fractional resurfacing, in our estimation, is the treatment of choice for facial acne scarring.

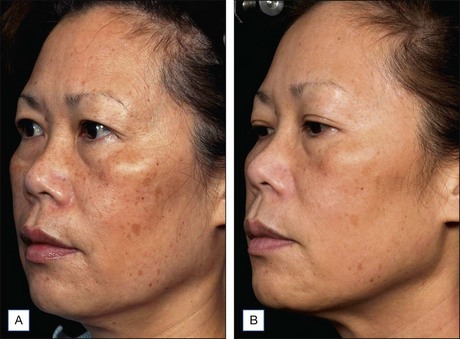

NAFR can also be safely used to treat acne scarring in darker-pigmented patients (Fig. 6.6). A study of 27 Korean patients with skin types IV or V that were treated with three to five non-ablative fractional resurfacing treatments revealed no significant adverse effects, specifically pigmentary alterations. Furthermore, all forms of acne scarring including ice-pick, boxcar, and rolling scars improved with eight patients (30%) reporting excellent improvement, 16 patients (59%) significant improvement, and three patients (11%) moderate improvement. With such a good efficacy and safety profile, many clinicians prefer NAFR to ablative fractional photothermolysis when it comes to treating acne scarring.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree