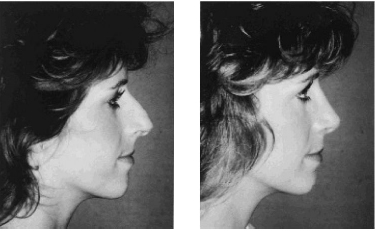

Most rhinoplasties are performed because the patient desires an improvement in appearance and/or nasal function. The patient may simply want a nose that is in harmony with the rest of the face rather than one that is out of proportion with respect to the other facial features (Fig. 12.1). On the other hand, it may be that the nose has been injured and is becoming progressively more disfigured the older the patient becomes.

At times patients have deformities of the inside of the nose that impair breathing or contribute to headaches or to sinus disease. These problems cannot be satisfactorily treated medically without simultaneously straightening the external nose.

Like faces, every nose is different; some noses are too long, some are too wide, some have large humps, some project away from the face, and so on.

A facial surgeon should strive to make each patient’s nose fit the rest of the face. If a surgeon was not properly trained to perform rhinoplasty and septoplasty, that surgeon should refer the patient to a colleague who specializes in the procedures.

The alterations recommended by a facial surgeon should be determined by many factors, including the patient’s height, age, skin thickness, and ethnic background and the configuration of other features such as the forehead, eyes, and chin. In short, the objective should be to achieve a natural-looking nose rather than one that appears to have been created by a surgeon.

In its simplest form, a well-conceived rhinoplasty is one in which anatomical structures that are in excess are removed or reduced, those that are deficient are augmented, and those that need no alteration are undisturbed.

I have published numerous articles (and a textbook1) on rhinoplasty. Each focuses on the intricacies of the procedure—specific aesthetic and functional techniques to accomplish the most “ideal” nose for a given patient. I have organized and conducted numerous continuing education seminars on rhinoplasty. Each one has dealt with preoperative assessment, surgical techniques, and postoperative management. Each has emphasized that there is no one-size-fitsall technique for any phase of the rhinoplasty operation. Rather it is a condition-specific exercise in surgical judgment and dexterity.

I do not subscribe to the ideology that every nose should be taken apart and reconstructed with grafts. Clearly, there are noses that require major reconstruction—those that have been mutilated by multiple surgeries or major trauma.

To date, I have performed nearly 6,000 rhinoplasties. As the numbers began to mount, I found myself removing less cartilage, especially in the nasal tip. The undesirable effects of aggressive removal of tip cartilage may not appear until 20 years have passed, but they are certain to appear.

In recent years, I have focused more on reshaping tip cartilages with sutures (similar to the technique described in my 1981 article “Systematic Approach to Correction of the Nasal Tip in Rhinoplasty2).” With additional experience and long-term follow-up, I have modified the technique since the original article was published. I recommend suture modification of tip cartilages, using sutures that dissolve within 6 to 8 weeks, when necessary. Permanent sutures are not necessary. After that time, the tissues will maintain the shape initially created by suturing.

The intent of this discussion on rhinoplasty is not to describe a step-by-step methodology. That is available in my book Nasal Plastic Surgery.1 Here, I wish to emphasize a condition-specific process of thought and several teaching points that led me to this way of thinking. The process is an algorithmic surgical progression derived from Ockham’s (razor) logic—when many options are possible, the simplest one is generally the correct one. This line of thinking will avoid disastrous outcomes and shorten the rhinoplasty “learning curve” for facial surgery colleagues. That same logic should be applied to the procedures discussed in the following chapters.

■ At What Age Can Rhinoplasty Be Performed?

An often asked question is at what age nasal plastic and reconstructive surgery can be performed. If a severe breathing problem (or headache issue) is present, even in a child, the anatomical obstruction should be conservatively corrected. With children, additional surgery at “maturity” may be required to obtain the optimal result. Certain limitations exist in children that preclude performing the definitive correction prior to puberty. Disturbing “growth centers” in the nose prior to maturity is thought to arrest nasal development.

Ordinarily, girls are mature enough to undergo rhinoplasty by the age of 15 (boys by age 17). However, I find it necessary to individualize this factor because some boys and girls mature at earlier ages. So that I can monitor their growth and maturation, I prefer to see these young men and women at whatever age they become interested in having a rhinoplasty, even though surgical correction may be delayed.

Early correction of unwanted nasal deformities can often give young people more self-confidence and improved self-esteem. A parent or guardian should always come with a minor to the consultation visit.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, approximately 30% of the rhinoplasties I perform are on patients over the age of 40. Many older patients remark that they have disliked their noses “all their life” and have now decided to have corrective surgery. Providing the patient is in good health, it is never too late in life to have a rhinoplasty. It is often performed as part of a facial rejuvenation program (along with facelift and eyelid plastic surgery) to improve the undesirable signs of aging.

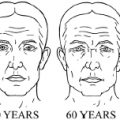

A longer drooping nose may be a “telltale” sign of aging, and repositioning of the drooping tip of the nose can be performed to give a more youthful appearance (Fig. 12.2).

Whenever a nasal airway problem is identified, the appropriate “functional” procedures are performed at the same sitting.

Fig. 12.2 With aging, the tip of the nose becomes longer due to loss of the tip support.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree