| 17 | My Personal Approach and Philosophy |

Revision rhinoplasty is a unique topic that distinguishes itself from primary cases in several important ways. The psychological aspect is less tangible, yet many patients have a more guarded outlook toward their doctor, the relationship, and promised results. The surgical plan is less predictable in revision rhinoplasty, because even the preoperative, anatomic diagnosis may be inaccurate. Degloving the nose may reveal unexpected variances in the nasal skeleton. The technical nuances of revision rhinoplasty are more complex and challenging because of the disruption of normal anatomic planes and landmarks. Moreover, the previously disrupted skin and soft tissue heal in an unpredictable manner. The nasal covering typically becomes thin, scarred, and less elastic and occasionally develops scattered dyschromias or telangiectasias. Earlier sections of this book cover targeted problems in secondary rhinoplasty, and this section is aimed at sharing more personal philosophies in terms of how I approach this patient group.

General Concepts

General Concepts

The patient who undergoes an unsuccessful rhinoplasty and seeks a second operation for definitive correction is generally more complex than may be realized on a first impression. The psychological aspect has been discussed earlier but cannot be overemphasized. Although the evaluation of every cosmetic patient warrants an assessment of motivation and expectations, this demographic must be more fully understood before committing to surgery. At the completion of each consultation, I must have a feel for three specific issues: motivation, expectation, and cooperation. The motivation for pursuing revision rhinoplasty, especially when not functional, can be complicated and deceptive. There are well-grounded reasons for seeking further improvement, but one must be wary of ulterior motives whereby additional surgery only serves to perpetuate a sense of inadequacy or imperfection. The specific expectations from surgery also must be defined and agreed on. Not only must they be achievable, but also all parties should agree that that is the desired outcome. Although controversial to many, computer imaging may have a distinct role in this regard. Patient cooperation is also important in terms of ability to abide by postoperative instructions, for example, avoiding sun exposure, trauma. This is more often an issue with young boys who are active in competitive sports.

During the initial consultation, the discussion may lead to the original surgeon and strong feelings of discontent toward him or her. A significant portion of time may be dedicated to the expelling of any pre-existing anger and redirecting the attention to the current condition and options for repair. On occasion, a patient may be seeking reinforcement or support for a deep-seated blame against the original surgeon. As a general policy, it is counterproductive to fuel that sentiment by discussing the original work, and I usually divert a conversation that heads in that direction. It is worthwhile, nevertheless, to get a sense of the original condition and the amount of change that has occurred and to determine exactly where the patient’s dissatisfaction lies.

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

The initial encounter moves from the global assessment to an analysis of the nose. This process begins with what I refer to as a “lay description” of the nasal features. It is often performed by patients themselves in front of a mirror and in response to “tell me what you see when you look at your nose—both what you like and don’t like.” This is an effective way of first allowing them to speak openly and unbiased by my opinions. Although it is usually performed in a somewhat random manner, this exercise does emphasize the most important aspect of the successful rhinoplasty: the patient’s perspective of the outside appearance, described in basic and simple terms. During this part, terms such as big, crooked, wide, pointy are used, rather than bifid, concave, saddle, and the like.

After this exercise, I perform my analysis sitting immediately in front of the patients as they look through the mirror. This initial assessment is a cutaneous description of the important landmarks of the face and nose, followed then by a determination of the bony and cartilaginous deformities that give rise to the external problems. It is done in a systematic way in three views: frontal, lateral, and base. One of the reasons for doing the evaluation in such a methodical manner rather than first addressing the obvious deformity or the area of greatest concern to the patient is to ensure that a complete analysis is performed without overlooking co-existing problems.

The frontal view looks at each of the vertical thirds independently, evaluated in terms of midline position, width, irregularities, definition, contour, and the brow-tip aesthetic line. Looking at the upper third independently from the middle vault or tip is critical to distinguishing different areas of pathology, especially in situations such as the twisted nose. Each region of the nose (and face) has an effect on the adjacent areas, and the illusions created can be powerful and deceptive. Performing the nasal analysis within independent subsites can help break down the effects of adjacent areas.

On lateral view, my analysis always begins with a deliberate assessment of the nasion and chin projection. I prioritize this analysis because of the ease with which abnormalities in these areas can be overlooked and the impact that omission may have. Moreover, patients are often unaware of deficiencies involving the radix or pogonion, thus directing the surgeon and the discussion to other more obvious areas. Next, each vertical third is again evaluated through the profile in terms of projection, rotation, and concavities. Revision rhinoplasty patients often have small degrees of disproportion with the ala–columella relation, usually unrecognized by the patient. Excessive columellar show is either secondary to a hanging columella (medial crura or caudal septum) or retracted alar rim. Other common profile finding with revision rhinoplasty include a loss of tip support and projection, a pseudo-hump, an unnatural or absent double break at the columella, blunting of the nasal–frontal angle, and a true pollybeak. The pollybeak deformity is the result of an inadequate resection of the anterior septal angle, whereas the pseudo-hump is the hump that appears after either overresection of the bony dorsum or from loss of tip support. The distinction is important and is made on lateral view. More often in secondary cases, the fullness or hump seen at the dorsum is improved by enhancing tip projection. This is counterintuitive to most patients, because their perception is that their nose is too large, and increasing projection of the tip is not considered.

The base view is less important to me in terms of aesthetics, and patients will comment only rarely on that perspective, as opposed to their image in pictures or what they see in a mirror. This submental view, however, can be very informative during the analysis, diagnosis, and surgical planning. Tip width, bulbosity, asymmetry, and projection can be accurately determined from this perspective. Nasal base width, alar contour, and tip lobule-columella proportions also are evaluated. It is important to take note of the length of the medial crura and position of the pods. When the medial crura are quite long with the pods resting on the nasal sill, surgeons should recognize that limited amount of deprojection can occur from releasing its ligamentous attachments to the caudal septum; more often, a direct excision or overlapping of the medial crura will be needed. In addition, the lateral aspect of both lateral crura should be inspected intranasally from this view and any recurvature of the lateral crura back into the vestibular airway carefully noted. Even if no nasal obstruction exists preoperatively, a tip-narrowing maneuver can exacerbate the recurvature and create new onset, iatrogenic nasal obstruction. This contour irregularity of the lateral crura must be corrected as a separate step if narrowing of the intermediate crura is still needed.

The oblique view provides an overview of the nose and how it is in balance with the face. It generally does not reveal specific findings except the occasional paramedian hump at the rhinion. Interestingly, many patients will recognize this and mention how a particular angle on photographs makes their “hump” look worse.

Anatomic Etiology of Structural Abnormalities

Anatomic Etiology of Structural Abnormalities

After the description of the cutaneous findings, we then move to identifying the structural abnormalities beneath the skin that give rise to the external deformities. This is a critical step in patient analysis, and it is often overlooked. Making the anatomic diagnosis is an essential step in determining the ideal method of repair, especially because a given external problem can have multiple different etiologies, each of which may be best corrected in an entirely different manner. The anatomic findings revealed during surgery should be consciously noted and correlated with the preoperative photographs. This is an invaluable opportunity to improve diagnostic skills in terms of matching the cutaneous features of a complex nose with their associated anatomic etiology at the level of the bony and cartilaginous framework.

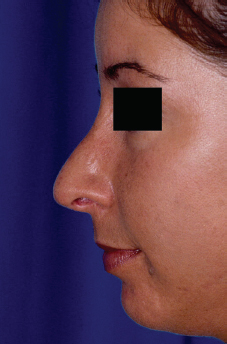

Problems of the upper third of the nose involve the nasal bones. If they are deviated or asymmetric, the nose will appear twisted. If overresected, the nasion will be too low, and it may give rise to a pseudo-hump (Fig. 17–1). If underresected, a persistent dorsal hump will be seen. If the nasal bones are left wide from incomplete lateral osteotomies, an open roof deformity will be left, and the caudal border of the bones will create the inverted-V deformity because they rest more laterally than the upper lateral cartilages. Small bony irregularities can be seen or palpated along the rhinion, especially if periosteum becomes shredded during rasping of the bones.

Figure 17–1 Low radix, easily overlooked as a dorsal hump.

Common middle vault problems seen in revision rhinoplasty include the hourglass deformity, in which the middle third becomes pinched and narrow. This is often associated with nasal obstruction at the level of the nasal valve. The anatomic etiology of this deformity is a progressive collapse of the upper lateral cartilages after they have become disarticulated off the dorsal septum during a hump resection (Figs. 17–2, 17–3). In addition, the normal septum has a flare at its dorsal margin where this increased width serves as a physiologic spreader graft. Once this portion of the septum is resected, the neodorsum is narrower and will lead to a pinched middle vault, even if the upper lateral cartilages are resuspended to the dorsal septum. For this reason, prophylactic spreader grafts are often needed after a hump reduction. The pollybeak deformity at the supratip region is the result of excessive septal cartilage along the anterior septal angle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree