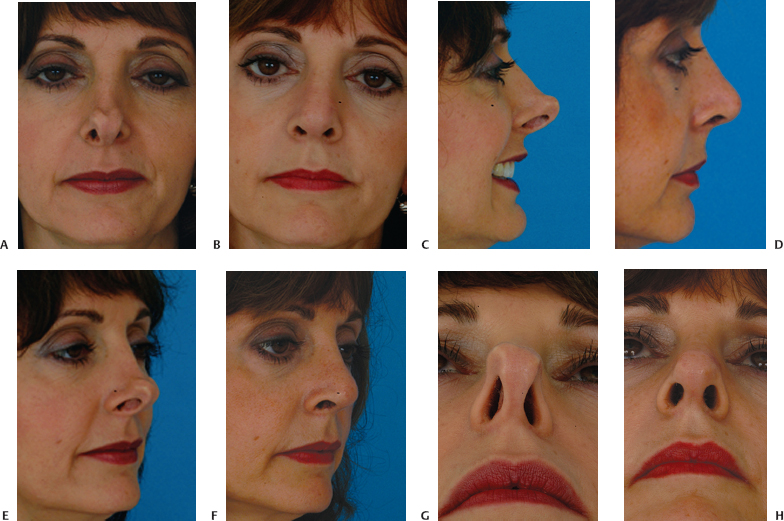

Revision rhinoplasty is a term that encompasses a wide spectrum of problems, from straightforward to complex. In an established revision practice, patients seeking consultation include many who have all but lost hope. Commonly, the experienced revision surgeon will find that significant improvement is possible (Fig. 18–1). However, to achieve success, it is important that the patient and surgeon come to a realistic understanding of what can and cannot be accomplished. Verbal communication supplemented by computer imaging helps the surgeon and patient arrive at a shared surgical goal.

The revision rhinoplasty patient needs an environment in which he or she will be able to develop and maintain trust. This environment is best created by dedicating oneself to revision surgery, by placing a strong emphasis on patient education, by taking the time necessary to answer the patient’s questions and concerns, and by being honest and plainspoken. The patient must feel that the surgeon has a passion for the operation and that the surgeon has dedicated him- or herself to the pursuit of excellence in nasal surgery, specifically revision surgery.

The revision patient is acutely aware that surgery is not an exact science and that complications can occur. The revision patient understands that complications also can occur in revision surgery; with this in mind, it is critically important that the surgeon show a special attention to risk management.

For many revision patients, life begins to revolve around their nose. It is important that patients be prepared for a shift in focus. They should be prepared to shift focus toward getting on with their lives after the important changes to their noses have been made.

The revision surgeon’s job does not end after surgery. If the result of a revision achieves the shared surgical goals, the surgeon should caution the patient to avoid the impulse to make additional small changes. The result should not become a “moving target.”

When there are problems that may benefit from additional work, naturally, the revision surgeon addresses them forthrightly. Conversely, it is important that the patient give thoughtful consideration to the recommendation by the experienced revision surgeon that no further surgery should be contemplated. In this setting (as in all aspects of patient care) it is important that the surgeon and patient have established a trusting relationship. Still, each patient ultimately bears a certain amount of responsibility for his or her own actions and decisions.

With the psychological, emotional, and technical factors in mind, it is important that the revision surgeon approach the nose with an emphasis on risk management. Surgery is not an exact science, and the results are not always predictable. The surgical plan is designed to achieve the shared surgical goals with as little trauma as possible. The patient is reminded that complications can still occur and that not all complications are correctable.

Ultimately, success in revision rhinoplasty is based on well-developed judgment, wisdom, and accumulated knowledge and experience. Like most surgeries, revision rhinoplasty is both a science and an art. Skill comes from experience and wisdom, combined with a measure of talent. The revision surgeon must have a detailed understanding of the multiple anatomic variants encountered. The surgeon must also have accumulated the appropriate surgical techniques and experience. Specifically, the revision surgeon must acquire knowledge of the surgical alterations that occur and how to achieve an improvement or correction when the result is undesirable. This second skill set is acquired by careful follow-up of operated patients over time.

My personal philosophy of revision rhinoplasty focuses on achieving two essential goals. The first is to make the patient happy. Hand in hand is the second goal: for this to be their last nasal surgery. With these goals and these introductory thoughts in mind, in this chapter I will discuss my personal philosophy and approach to revision rhinoplasty in terms of the psychological, nontechnical aspects, as well as the technical, surgical aspects. I will provide my general thoughts and a “run-through” of my current approach. Instead of a “theoretical” discussion, this chapter provides a “brass tacks” description of my approach to patients and my practical thoughts on the subject of the practice of revision rhinoplasty. It is my hope that this information will be useful to the reader.

Psychology of the Revision Rhinoplasty Patient

Psychology of the Revision Rhinoplasty Patient

The revision patient is an individual who sought elective cosmetic surgery and, having understood the risks of a complication, is faced with a result that falls short of his or her expectations in some respect. All rhinoplasty surgeons have complications. The literature reports complication rates in the range of 8 to 15%.1–8 Complications can occur despite surgery that has been technically well performed. Regardless of the cause of a complication, it is important that complications be recognized and forthrightly addressed when they occur. Generally, a complication is correctible to some degree; on rare occasion, no improvement is possible.

Revision patients who seek care from their primary surgeon have retained confidence and trust in their surgeon. Revision patients who seek care from someone other than their primary surgeon have, by definition, (and whether fairly or unfairly) lost confidence in their initial surgeon. These patients often require emotional support.

Revision patients often experience significant distress because of their unfavorable outcome. Generally speaking, these are people who sought elective, cosmetic rhinoplasty and understood that there was a risk of an unfavorable result. Faced with an unsatisfactory result, some revision patients feel angry with themselves for “not having done more research.” Each time they look in the mirror, they are reminded of their “bad decision.” Having placed their trust in a surgeon, they now find it difficult to go through this process again. They seek not only to regain a favorable appearance but also to regain control.

It is fairly common that, early in an initial consultation for revision rhinoplasty, patients cry as they describe their condition to me. During the office visit, I directly address my observations as to the emotional effect that the unfavorable outcome has caused. I have found that patients appreciate knowing that I understand how they feel.

An occasional patient will benefit from psychiatric consultation as a part of his or her overall care.9 I have found that patients have been responsive and have accepted this recommendation from me when I have made it.

Patients seek emotional support on their own, often from other patients. The emergence of Internet chat rooms and message boards has provided an outlet for patients to exchange ideas, information, and experiences. These patients provide non-professional reassurance and emotional support for each other—as people with a “shared experience”—as they proceed through the revision process. I have observed that this can be a favorable support, but more often it creates considerable anxiety in patients. Although this arena is largely outside of the surgeon’s control, it is important to have some understanding that this sort of interaction occurs with increasing frequency.

For patients who have made a decision for surgery, we make available the opportunity to speak with former revision patients. This is optional. We explain that the intention is to provide an opportunity to find out about a “typical” surgical experience from someone who “isn’t wearing a white coat.” We make it clear that this is a happy patient who has had successful revision rhinoplasty. I do not make this opportunity available until after a decision to proceed with surgery is made. I have found this offer to be useful in helping some patients understand the revision process from start to finish. In addition, it may help allay some of the new patient’s anxieties and worries, once the decision for surgery has been made.

Patient Consultation

Patient Consultation

Medical History, Photographic Documentation, Patient Goals

The patient is greeted and, if he or she has not done so already, is asked to fill out a detailed history form. He or she is then taken to the photography room by a nurse assistant, who takes digital photographs and escorts the patient to the examination room. The nurse then downloads the photographs into the network computer.

I then meet the patient. I ask what he or she does not like about his or her nose and what the patient would like me to fix. After the patient explains the goals, I review any prior medical records. After a review of the patient’s medical history, I then perform an examination.

Aesthetic Nasal Examination

Detailed anatomic analysis of the nose is an essential first step in achieving a successful surgical outcome. My approach to rhinoplasty analysis in a primary rhinoplasty is well described.10 I use this organized approach to aesthetic analysis for revision rhinoplasty as well (Table 18–1). The nasal analysis in revision rhinoplasty is made more complex by the fact of prior surgical intervention, with subsequent distortion of the pre-existing anatomy.

The first, critical factor is the skin-soft tissue envelope—its thickness, its quality, its integrity, and its mobility in relation to the underlying nasal structures. As analysis proceeds, a critical question that guides examination of each area is, “was it underresected, overresected, asymmetrically resected, or appropriately treated?” Any unoperated areas of the nose are identified. In addition, the presence of possible grafts or implants is considered throughout the examination. A partial list of specific considerations is discussed here.

For the bony dorsum, I examine the osteotomies and assess their position. Are they too high, normal, or too low? Is the bony dorsum straight or twisted, wide or narrow? Will revision osteotomies be required? I look for the presence of open roof deformity or rocker deformity. In addition, I judge whether the bony hump was underresected or overresected. In addition, I palpate the bony hump for irregularities.

For the middle vault, I assess the middle vault width, with special attention directed to the presence of an inverted-V deformity. A narrow middle vault with an inverted-V deformity suggests a need to restore middle vault structural support (i.e., spreader grafts). I make a judgment as to whether the cartilaginous profile was underresected, overresected, or irregularly resected and whether the middle vault is straight or deviated. In addition, I palpate carefully to ascertain whether the dorsal septum at the anterior septal angle was underresected, contributing to a pollybeak deformity.

For the tip, I carefully examine and assess tip symmetry, projection, rotation, alar–columellar relationship, and lower lateral crural characteristics such as overresection and bossae formation. I palpate to assess tip support. I examine the caudal septum to see if it is straight or twisted. I examine all incisions, both endonasal and external. I examine carefully for the presence of possible grafts.

Functional Nasal Examination

Static and dynamic nasal valve collapse are commonly encountered in revision rhinoplasty patients.11–16 In Becker et al.’s report, 19 of 21 patients with nasal valve collapse reported a history of rhinoplasty.16

Pinching of the nasal sidewall and alar retraction are hallmarks of nasal valve collapse (Fig. 18–2). Observing the patient performing normal and deep nasal inspiration may lead directly to the diagnosis of nasal valve collapse. A “modified” Cottle maneuver, in which the lateral nasal sidewall is supported and elevated slightly with a cerumen curette of similar device, is strongly supportive of the diagnosis when the maneuver results in the patient’s report of significant subjective improvement in nasal breathing.

Anterior rhinoscopy is undertaken and may help identify abnormalities such as deviated septum, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, synechiae or scar bands, septal perforation, and other abnormalities. Examination also includes nasal endoscopy when there is a complaint of nasal obstruction.17,18 If indicated, a sinus computed tomography scan may also be obtained.

Pownell et al. described diagnostic nasal endoscopy in the plastic surgical literature.17 They traced the historical development of nasal endoscopy, explained its rationale, reviewed anatomic and diagnostic issues including the differential diagnosis of nasal obstruction, and described the selection of equipment and correct application of technique, emphasizing the potential for advanced diagnostic potential.

Levine18 reported that 39% of patients with a complaint of nasal obstruction had findings on endoscopic examination that were not identified with traditional rhinoscopy. Many of Levine’s patients had seen other physicians for this problem and had not received appropriate treatment.

| *There are many other points of analysis that can be made on each view, but these are some of the vital points of commentary. | |

| General | |

| Primary concerns | Identify primary concerns leading patient to seek revision rhinoplasty. |

| Skin quality | Integrity, vascularity, mobility, skin thickness (thin, medium, or thick). |

| Problems | For each issue and anatomic area, is problem because of underresection, overresection, asymmetric resection? |

| Frontal | |

| Width | Narrow, wide, normal, “wide–narrow–wide”? |

| Dorsum | Twisted or straight (follow brow-tip aesthetic lines)? |

| Open roof? | |

| Rocker deformity? | |

| Visible or palpable deformities? | |

| Prior osteotomies? If so, normal or abnormal? | |

| Middle Vault | Assess width. Inverted V? Underresected? Overresected? |

| Asymmetric? | |

| Tip | |