CHAPTER 65 Minimally Invasive Total Hip Arthroplasty

Although some studies suggest a benefit for patients undergoing minimally invasive THA, many surgeons remain skeptical that these changes in surgical technique are responsible for the observed improvements in early postoperative function. Over the same time frame in which minimally invasive surgery has emerged, surgeons have refined the entire perioperative process with a variety of strategies used before, during, and after surgery. THA candidates are increasingly more educated about the surgical experience and the expected rehabilitation process. By aligning patient and surgeon expectations, more rapid rehabilitation can be achieved than was the norm only a decade ago.1 During the preoperative period a substantial advancement has been the adoption of more effective anesthetic and multimodal analgesia protocols.2 These protocols minimize pain and allow for more rapid rehabilitation by minimizing the side effects of narcotic medications such as somnolence, urinary retention, nausea, vomiting, and postoperative ileus. Postoperatively, patients are in less pain because of these analgesic advancements and therefore participate in physical therapy earlier and leave the hospital more rapidly. These advancements have coincided with the introduction of minimally invasive surgical techniques, and it has been difficult to objectively determine precisely which factors are responsible for improved patient outcomes. Furthermore, some surgeons have selectively applied the minimally invasive surgical techniques to only younger or nonobese patients—patients who are predisposed to do well. Therefore the benefits of minimally invasive surgical techniques remain unclear. The goal of this chapter is to review the most commonly used minimally invasive surgical approaches for THA, the advantages and disadvantages of each of these techniques, and the available clinical data regarding these techniques.

APPROACHES

Mini-Posterior (Mini-Posterolateral)

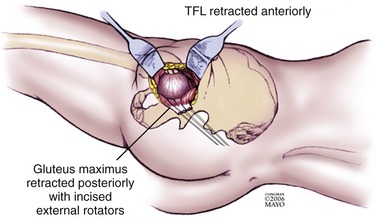

One commonly used technique for mini-posterior THA is the one described by Dorr and colleagues.3 Briefly, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position and an approximately 8-cm skin incision is made along the posterior border of the trochanter extending from the tip of the greater trochanter to the level of the vastus tubercle on the femur. A fascial incision is then made extending proximally in line with the fibers of the gluteus maximus (Fig. 65-1). Finger dissection is then used to find the plane between the gluteus medius and the minimus. An L-shaped incision of the capsule and external rotators is made that parallels the inferior border of the gluteus minimus, is carried to the piriformis fossa, then is turned distally to incise the external rotators from the greater trochanter ending at the proximal edge of the quadratus femoris. The hip is then dislocated and the femoral neck cut is made in accordance with preoperative planning. The acetabulum is visualized with a minimal anterior capsulectomy. Curved reamers and/or computer navigation can be used to assist in acetabular reaming. The real acetabular component is then inserted. The osteotomized femur is delivered through the incision, and specialized retractors are placed near the femoral neck to facilitate femoral preparation and insertion of the trial stem and then the real stem. The posterior capsule and external rotators are repaired either through drill holes in the greater trochanter or by using a soft-tissue repair that approximates the external rotators and capsule to the inferior edge of the gluteus minimus and the cut edge of superior hip capsule. The overlying fascia and skin are then closed.

A distinct advantage of the minimally invasive posterior approach is its familiarity for most reconstructive surgeons. This approach can be easily converted to a standard posterior approach if visualization proves suboptimal or if a complication develops. The technique involves less muscular dissection than the standard posterior approach, which may decrease intraoperative blood loss and postoperative pain and may facilitate more rapid rehabilitation and hospital discharge. A recent cadaver study showed that the mini-posterior approach caused less muscle damage than the two-incision minimally invasive technique for THA.4

The major disadvantage of the minimally invasive posterior approach has been suboptimal component position. Woolson and associates demonstrated in a comparative study that the acetabular component was malpositioned twice as often and the femoral component was malpositioned three times as often in patients who underwent a minimally invasive posterior approach versus patients who underwent a standard posterior approach.5 The acetabular component tends to be placed in an excessively vertical position. The femoral component tends to be placed in a flexed position owing to a posterior starting point in an attempt to avoid injuring the skin at the proximal end of the incision. Subsequent studies by Sculco and colleagues and others6,7 showed a lower prevalence of malposition and attributed the earlier findings of Woolson to the learning curve of the surgeons involved in the study. A second disadvantage is that the proximal skin of the incision is at risk for abrasion during femoral broaching, and the surgical team must be diligent to protect this skin. Woolson’s study demonstrated an increased prevalence of wound complications in patients treated with a minimally invasive posterior incision when compared with those treated with a standard incision.

Recent randomized studies have compared the standard posterior approach to the minimally invasive posterior approach. Chimento and colleagues demonstrated an advantage with the mini-posterior technique for patients with a body mass index of less than 30.8 These patients had less intraoperative blood loss, less total blood loss, and less limping at 6 weeks after surgery. However, there was no difference detected in functional outcomes at 1 and 2 years. Larger studies have suggested little benefit of the mini-posterior approach over the standard posterior approach. Ogonda and colleagues demonstrated no significant difference in postoperative hematocrit, blood transfusion requirements, pain scores, or analgesic use in two groups of patients randomized to standard posterior incision versus minimally invasive posterior approach.9 Moreover, there was no functional difference in early walking ability or length of inpatient hospitalization. The functional outcome scores 6 weeks postoperatively were the same. A comprehensive gait analysis study by this same group of investigators showed no difference between patients who received the minimally invasive approach versus the standard posterior approach.10,11 Specifically, there was no difference in gait velocity, ease of transfers, stair climbing, and the use of gait aids at 2 days and at 6 weeks.

Wenz and colleagues studied the patients who had a mini-posterior approach and retrospectively compared their outcomes with patients who underwent THA via a traditional direct lateral approach.12 The mini-posterior incision group required less operative time, had less blood loss, and required fewer intraoperative blood transfusions. The prevalence of intraoperative and postoperative complications was not significantly different between the two groups. Postoperatively, the mini-posterior incision group required fewer blood transfusions. Radiographic analysis showed adequate component position and cement mantle in both groups. The only difference noted was a slight tendency toward valgus placement of the femoral stem in obese patients in the mini-posterior incision group. Early functional outcomes favored the mini-posterior incision group, with more patients able to ambulate on postoperative day number 1 and fewer patients requiring assistance from physical therapy. Fewer mini-posterior incision patients required skilled nursing care after hospital discharge. There was, however, no decrease in length of hospital stay.

Mini-Anterolateral

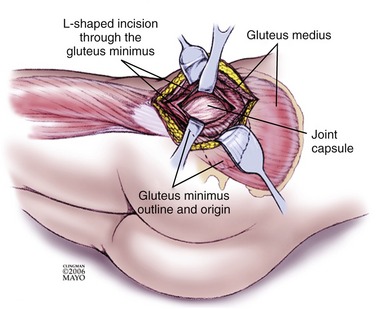

To minimize the risk of dislocation, an anterolateral approach has been advocated by many for THA. A modification of this approach has been developed for minimally invasive THA.13 Briefly, with the patient in the lateral position a 3-inch incision is made, angled 25 to 30 degrees anterior to the femur from posterosuperior to anteroinferior direction centered  inch distal to the tip of the greater trochanter. The fascia is incised; the anterior 25% of the gluteus medius is then divided at the junction of the anterior and superior trochanter. The gluteus minimus is then transected in an L-shaped fashion (Fig. 65-2). The leg is then slightly externally rotated as the anterior abductors are detached from the trochanter. This exposes the capsule, and its anterior portion is excised. The hip can then be slowly dislocated without the remaining abductors being damaged. A provisional femoral neck cut is made to better visualize the lesser trochanter, and then a definitive femoral neck cut can be made based on preoperative templating.

inch distal to the tip of the greater trochanter. The fascia is incised; the anterior 25% of the gluteus medius is then divided at the junction of the anterior and superior trochanter. The gluteus minimus is then transected in an L-shaped fashion (Fig. 65-2). The leg is then slightly externally rotated as the anterior abductors are detached from the trochanter. This exposes the capsule, and its anterior portion is excised. The hip can then be slowly dislocated without the remaining abductors being damaged. A provisional femoral neck cut is made to better visualize the lesser trochanter, and then a definitive femoral neck cut can be made based on preoperative templating.

The main theoretical advantage of the minimally invasive anterolateral approach is a lower risk of dislocation as compared with the standard posterior approach. Proponents of the mini-anterior approach believe that it transects less muscle and tendon than the traditional anterolateral approach and results in a short inpatient stay, faster recovery, and better cosmesis.13 Those contentions have not been supported by any prospective or retrospective controlled trials.

Mini–Watson-Jones

The classical Watson-Jones anterior approach has been associated with more hip stability then the classical posterior approach, but at the expense of an increased likelihood of postoperative limp caused by abductor weakness. This is a result of the violation of the gluteus minimus and medius in this approach. The minimally invasive Watson-Jones approach is a modification of this classic approach.14

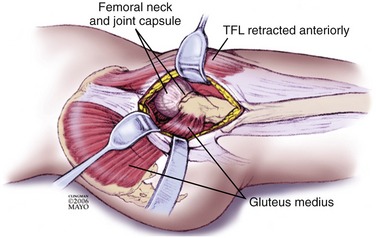

The skin incision is made over the anterior tubercle of the greater trochanter and extends to the anterior superior iliac spine for about 6 to 7 cm. After the subcutaneous tissue and the fascia are divided in line with the skin incision, the intermuscular plane between the tensor fasciae latae and the gluteus medius is bluntly dissected and the anterior and superior portions of the femoral neck are palpated (Fig. 65-3). Hohmann retractors are placed along the superior and inferior femoral neck, and a U-shaped capsulotomy is then made. The femoral head is removed via a series of two osteotomies, both made in external rotation. The first osteotomy is made at the junction of the femoral head and neck; after this cut, the second is made with reference to the greater trochanter in accordance with the preoperative plan. Once these two cuts have been made, the femoral neck piece and the femoral head can be removed, thus allowing visualization of the acetabulum.

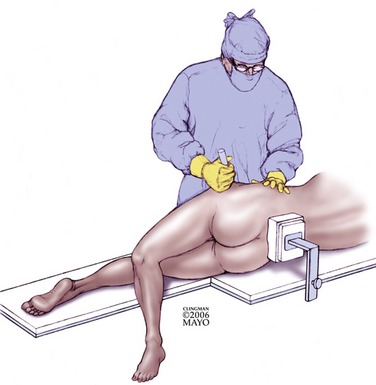

The acetabulum can be then optimally visualized with two or three Hohmann retractors; the capsule and any intervening soft tissue are removed before the acetabulum is reamed and prepared. Once the acetabular component has been placed, attention is turned to the femur. The leg is placed in a posterior pocket that requires the leg to be placed in extension (Fig. 65-4). An elevating retractor such as a hip skid is used in conjunction with a Hohmann retractor to present the femur and minimize damage to the abductors. The femur is prepared, and the trial components are tested before insertion of the real femoral component. Once the final components are in place, the closure includes direct repair of the capsulotomy and the abductors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree