Fig. 19.1

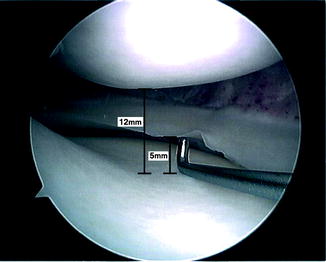

Arthroscopic view of a left knee, suggesting Grade 2+ MCL laxity

Fig. 19.2

Arthroscopic view of a right knee, suggesting Grade 3+ MCL laxity

Surgical Approaches to Address MCL Dysfunction

Direct repair with medial and posteromedial plication/reefing: Direct repair with medial plication has been described in the setting of primary ACL reconstruction [10, 12]. We use this technique in the setting of revision ACL reconstruction when there is mild increased side-to-side laxity in the MCL [10].

Surgical technique [10]: After the ACL graft is fixed and medial opening of > 5 mm is observed with the use of the arthroscopic probe, a short longitudinal incision over the medial epicondyle is made (Fig. 19.3). The retinaculum is then incised to reveal the medial ligament structures (Fig. 19.4). The MCL and POL are then sutured proximally to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 19.5) with three figure-of-eight sutures using Number 2 Ethibond® (Ethicon) (Fig. 19.6). The figure-of-eight sutures advance the MCL and POL proximally towards the medial epicondyle. Each is started at the area of the medial epicondyle and extends approximately 1 cm distally, one aiming directly distally, one aiming distally and slightly anteriorly, and one aiming distally and slightly posteriorly (the direction of the POL). The sutures are tied and tension is checked in extension and in flexion (Fig. 19.7). Postoperative rehabilitation guidelines are similar to those for isolated ACL reconstruction with two exceptions: keeping crutch-protected gait for 4 weeks, and using a knee brace for 6 weeks without motion restriction. Weight-bearing is permitted as tolerated from the day after surgery. Recently, in a group of 36 patients with a mean age of 37 years (range, 15–70), who underwent this technique and were followed for more than 2 years, the following outcomes were reported [10]: mean subjective IKDC score improved from 36 preoperatively to 94 at latest follow-up, mean KOOS improved from 45 preoperatively to 93 postoperatively, mean Lysholm score improved from 40 preoperatively to 93 postoperatively, and valgus and external rotation laxities were normal in all cases.

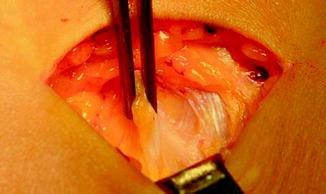

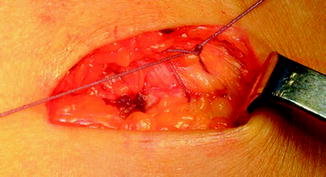

Fig. 19.3

A small incision over the medial epicondyle. Reprinted from Canata GL, Chiey A, Leoni T. Surgical technique: does mini-invasive medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament repair restore knee stability in combined chronic medial and ACL injuries? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:791–797, with permission from Springer

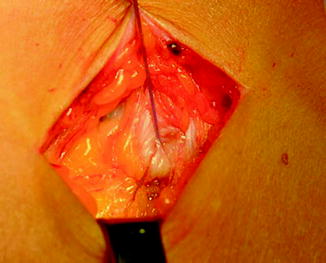

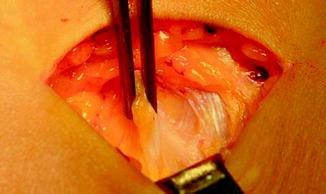

Fig. 19.4

Laxity of medial restraints is shown. Reprinted from Canata GL, Chiey A, Leoni T. Surgical technique: does mini-invasive medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament repair restore knee stability in combined chronic medial and ACL injuries? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:791–797, with permission from Springer

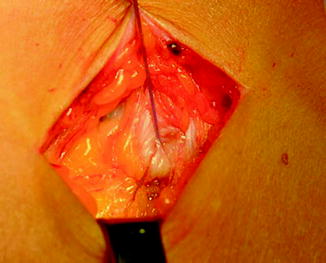

Fig. 19.5

Medial tissue is tightened up to the epicondyle area. Reprinted from Canata GL, Chiey A, Leoni T. Surgical technique: does mini-invasive medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament repair restore knee stability in combined chronic medial and ACL injuries? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:791–797, with permission from Springer

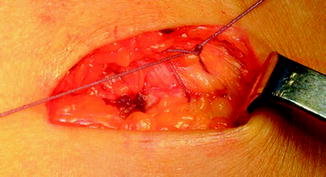

Fig. 19.6

Nonabsorbable sutures placed in the MCL. Reprinted from Canata GL, Chiey A, Leoni T. Surgical technique: does mini-invasive medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament repair restore knee stability in combined chronic medial and ACL injuries? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:791–797, with permission from Springer

Fig. 19.7

End of procedure (MCL and POL have been advanced proximally to the medial epicondyle). Reprinted from Canata GL, Chiey A, Leoni T. Surgical technique: does mini-invasive medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament repair restore knee stability in combined chronic medial and ACL injuries? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:791–797, with permission from Springer

MCL reconstruction: This procedure should be reserved for revision ACL cases where Grade 2+ or 3+ medial laxity is detected. Surgical techniques which have been described to reconstruct the MCL include semitendinosus autograft with preservation of the tibial insertion [13–16], allograft tissues [17, 18], and double-bundle reconstructions [8, 15, 17–19]. Drawbacks related to these techniques include a long incision across the medial aspect of the knee with up to 20° loss of knee flexion or extension in 20 % of the operations [16], keeping the semitendinosus insertion distally and using it as an MCL graft [13–16] resulting in a too-anterior tibial attachment (i.e., the tibial insertion of the MCL should be posterior to the pes anserinus [4, 20]), harvesting a dynamic medial stabilizer that applies adduction moment during gait (i.e., semitendinosus) in a knee with medial laxity, and the relative complexity of double-bundle reconstructions, compared to single-bundle reconstructions, corresponding to their need for multiple attachment sites on the femur as well as on the tibia and more graft tissue, and number of fixation devices (i.e., screws, washers, staples, etc.) required [8, 15, 17–19].

Recently, we described a new technique to reconstruct the MCL that uses Achilles tendon allograft [11]. Benefits include avoiding donor site morbidity, secure fixation with bone-to-bone healing on the femur, small skin incisions that do not cross the knee, and isometric reconstruction. Open physis of the distal femur is an absolute contraindication for this procedure. Relative contraindications for this surgery include any factor that may substantially increase the risk of postoperative complications. These include: (1) active infection; (2) inability to adhere to postoperative rehabilitation guidelines; (3) severe soft tissue trauma; and (4) comorbidities such as diabetes and morbid obesity.

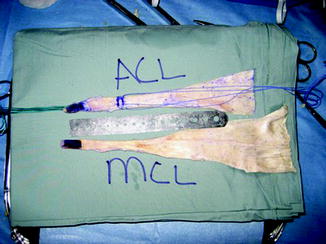

Surgical technique [11]: With the patient under anesthesia, after confirming MCL laxity that requires reconstruction as indicated previously by physical examination and arthroscopic examination, the following steps are carried out (after fixing the cruciate graft on the femur only): (1) the Achilles allograft is prepared creating a 9-mm diameter by 18-mm length bone plug (Fig. 19.8); (2) a 3-cm longitudinal skin incision is made over the medial femoral epicondyle; (3) a guide pin is inserted 3–5 mm proximal and posterior to the medial femoral epicondyle, parallel to the joint line, and in a 15° anterior direction to avoid the intercondylar notch. Location of the pin is confirmed with fluoroscopy (Fig. 19.9); (4) the skin is undermined from the femoral guide pin to the anatomic MCL insertion on the tibia, creating a tunnel for the graft under the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 19.10); (5) a nonabsorbable suture loop is placed around the guide pin and brought distally under the skin through the tunnel just created; (6) the distal suture is held against the tibia at the estimated anatomic insertion, just posterior to the pes anserinus insertion. Isometricity is tested through knee motion from 0 to 90°. The tibial insertion point is modified, if needed, until the loop is isometric; (7) the isometric point is marked on the tibia with a Bovey; (8) soft tissue around the femoral guide pin is débrided to allow for insertion of the Achilles bone plug into a socket created around this pin later; (9) a 9-mm diameter reaming is performed over the guide pin to a depth of 20 mm; (10) the Achilles bone plug is inserted into the femoral socket and fixed with a 7-mm diameter by 20-mm length metal interference screw; (11) the Achilles tendon tissue is passed under the skin and distally; (12) the cruciate graft is now tensioned and fixed on the tibia; (13) the MCL graft is tensioned with the knee at 20° flexion under varus stress and fixed at the isometric point on the tibia with a 4.5-mm cortical screw and a 17-mm spiked washer (Fig. 19.11); and (14) subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed. Tunnels position and hardware placement are confirmed postoperatively with radiographs (Fig. 19.12).