Surgical correction of the crooked nose is a difficult problem, and revision of failed surgical attempts can be even more challenging. The crooked nose often has both functional and aesthetic abnormalities, and the cornerstone of correction begins with a proper preoperative analysis. In this chapter, we will discuss analysis of the crooked nose; common pitfalls that frequently lead to failures; and techniques of osteotomy, septoplasty, and grafting that can be used to address the functional and aesthetic problems.

Rhinoplasty is considered one of the most difficult and unpredictable surgical procedures in head and neck surgery. Converse wrote that the most important causes of unfavorable rhinoplasty results were poor surgical judgment and the surgeon’s inexperience.1 Stucker further extrapolated that the most common postoperative deformity was an uncorrected defect compounded by surgery.2 The ideal rate of revision of primary rhinoplasty has been suggested to be in the range of 5 to 10%, with a 20% rate for revision cases.2 The most challenging and common complication after rhinoplasty of the crooked nose is recurrent or persistent deviation. In some cases, the recurrence is unpredictable and unexpected. In other cases, as with patients with severe facial asymmetry, postoperative deviation of the nose may be expected and unpreventable.

The traumatized nose and septum are thought by some to be the underlying etiology of most crooked noses.3 TerKonda and Sykes claimed that most crooked noses without a history of trauma are caused by “unrecognized” birth or early childhood trauma.3 They attributed asymmetric growth that manifests at puberty to an earlier insult of the nasal septum. Rohrich and Adams, in their article on the management of the traumatized nose, commented that the incidence of postreduction nasal deformities requiring subsequent rhinoplasty ranges from 14 to 50%, with the highest rate of 40 to 42% in patients identified with significant septal deviation.4 They credited unrecognized septal deformities with being the major cause of recurrent deviation of the nasal dorsum after closed reduction of the nasal fracture. Their article highlights the importance of evaluation and repair of the septum as a key component of long-term correction of the traumatized nose. Unrecognized deviation of the septum not only is important in postreduction of nasal fractures but also is a frequent cause of the persistently crooked nose in primary rhinoplasty surgery.

Causes of recurrent deviation other than uncorrected septal deviation at the time of primary rhinoplasty include soft tissue scar contracture that displaces the nose during the healing process, asymmetric osteotomies, asymmetric resection of the upper lateral cartilages (ULCs), dislocation of the ULCs, asymmetric tip or dome work, and trauma during the healing phase (Table 8–1). Common things missed on evaluation that lead to a persistent crooked nose are unrecognized facial asymmetry, high anterior septal deviations, asymmetric lower lateral cartilages, and asymmetric ULCs. Therefore, thorough preoperative analysis is the cornerstone of management of the persistently crooked nose.

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

A thorough history with an emphasis on nasal trauma, airway complaints, and previous surgery should be obtained. The date of past operations is important to obtain because it may affect the timing of revision surgery. Adequate time for healing and scar maturation needs to be allowed, and this frequently requires 12 to 18 months. Although it is easy for the surgeon and patient to become focused on the external nasal deformity when the deformity is severe, the surgeon must not forget to address the patient’s airway complaints in addition to aesthetic concerns. A rhinoplasty patient with both a functionally compromised airway and a crooked nose has a complex problem that requires extensive preoperative analysis to ensure consistent surgical outcomes. Frequently, the functional and aesthetic concerns of the patient are contradictory; patients will often request a smaller nose with a larger and more functional nasal airway. Preoperative patient education must emphasize that not all goals are attainable if adequate airway function is to be maintained or improved because many patients will express an unreasonable aesthetic desire for a nose that will be either too narrow or too deprojected to maintain a functional airway.

Physical examination of the patient with a crooked nose begins with a global assessment of facial symmetry. To locate the midline of the face, we generally identify multiple points, including the central glabella, intercanthal midline, nasal tip, nasal dorsum, philtrum, central upper incisors, and pogonion (menton). A line connecting these points helps evaluate facial symmetry and can be used to determine whether the problem is global or confined to the nose. Dividing the face into vertical fifths based on the intercanthal distance will help point out any existing facial asymmetry. In patients with crooked noses, it is not uncommon to find one side of the face slightly smaller and underdeveloped, with a mild form of hemifacial microsomia. It is important that the surgeon bring these asymmetries to the attention of patients, because they often are unaware of this problem. Patients must understand that rhinoplasty surgery alone will not correct this asymmetry and that it may be impossible to create a perfectly straight nose on a crooked face.

| Bony Pyramid |

| Depression of one bone |

| Depression of one bone, elevation of the other |

| Asymmetry caused by an unanticipated oblique back fracture |

| Asymmetry of nasal wall length or contour |

| Asymmetry of the piriform aperture |

| Dorsum |

| Asymmetric ULCs |

| Dislocation of ULC from nasal bone or septum |

| High septal and ULC deformity |

| Asymmetric collapse of the middle nasal vault |

| Tip |

| Asymmetric LLCs |

| Asymmetric tip bossae |

| Caudal septal deviation |

| Displacement of LLC |

| Septum |

| C-shaped deformity with displacement of inferior septum off the maxillary crest |

| High internal septal deviation |

| Dorsal septal deviation |

| Displaced nasal spine |

| Displaced septal angle |

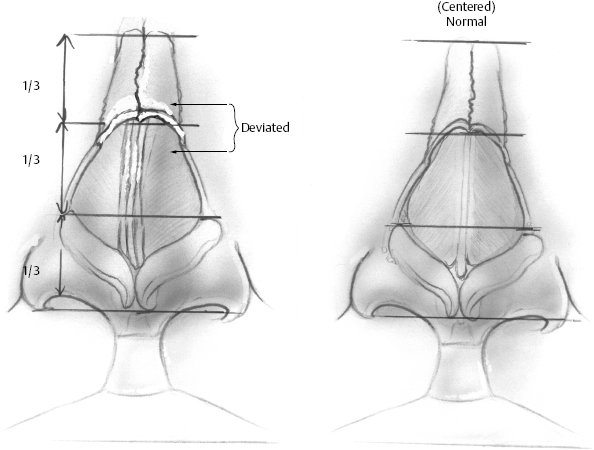

Next, an analysis of the external nose from top to bottom is performed. The nose is divided into vertical thirds (upper, middle, and lower), and each third is compared with the previously identified midline to determine if the site is central or deviated to the right or left (Fig. 8–1). The upper third corresponds to the nasal bones, nasal process of the frontal bone, and the frontal process of the maxilla. The middle third corresponds to the ULCs, the septum and the piriform aperture. The lower third corresponds to the septum, nasal spine, and the LLCs. Determining the sites of deviation after dividing the nose into thirds is important, because each third is addressed differently surgically. The position, size, shape, and strength of the nasal bones, ULCs, and LLCs should be inspected and qualified. The symmetry of tip defining points, bossae, surgical scars, and the nasal ala also should be noted. Finally, the nasal airway must be thoroughly examined in terms of the mucosa, septum, turbinates, and nasal valve function before and after topical decongestion. A thorough intranasal examination using inspection and palpation can determine the quality and quantity of septal cartilage present and available for harvesting if grafts are necessary. The surgeon must also identify posterior and superior deflections of the septum that can be easily overlooked if one is not careful. Palpation should be used to determine the position of the nasal spine and septal angle and to qualify the amount of tip support present. The Cottle maneuver and manipulation of the LLCs are important in evaluation of the function of the internal and external nasal valves.

Figure 8–1 The nose is divided into horizontal thirds. Each segment can be either midline or deviated to the left or right of center. The right figure is centered in all three horizontal thirds. The left figure is deviated in both the upper third and middle third but centered in the lower third. Preoperative analysis of the nose in this way will determine which surgical procedures will be necessary. Deviations of the upper third generally require the use of osteotomies, whereas deviations of the central third are sometimes corrected with asymmetric reduction and contralateral grafting.

Standard rhinoplasty photographs of the patient should always be obtained and analyzed. Occasionally, evaluation of the photographs will identify issues not clarified during the physical examination. We find that photographing a second “seminasal” base view, with the patient’s neck less extended, is helpful because it includes the tip and the entire length of the nose; therefore, it is helpful in clarifying areas of asymmetry in all three divisions of the nose (Fig. 8–2).

In the case of revision rhinoplasty on a patient with a persistently crooked nose, the surgeon must be prepared to deal with the consequences of prior surgery. For example, what, if any, septal, ear, or rib cartilage grafts were used and where were they placed? What is the status of the lower cartilages? How much septum was resected? These are sometimes difficult to ascertain on physical exam or from patient history. To that end, it may be helpful to obtain outside records and previous operative reports.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Surgical approaches to the crooked nose must address both the functional and aesthetic aspects of the nose. Sometimes functional concerns outweigh the aesthetic concerns or vice versa. The two primary philosophies regarding correction of the crooked nose are (1) deconstruction/reconstruction and (2) camouflage. These are not mutually exclusive, and a combination of these techniques may be used. Historically, the most common approach has been the former. In this approach, aggressive mobilization of the septum and bony pyramid is undertaken using standard septoplasty and osteotomy techniques to straighten the central structural support of the nose. This approach necessarily destabilizes the nose and relies on postoperative scar and bone formation to permanently restabilize the framework. This approach may result in unpredictable postoperative outcomes and recurrent asymmetry. The camouflage approach avoids aggressive deconstruction and places a greater emphasis on grafting to obtain the desired aesthetic result.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree