The primary focus of this chapter will be on the patient who has had previous surgery. Many of the analytical features and technical points presented, however, can be applied to the patient seeking consultation in primary rhinoplasty and to patients with similar characteristics after trauma. Revision rhinoplasty is a complicated endeavor with a myriad of anatomic challenges admixed with the interaction of the surgeon navigating the intricate emotional, motivational, and, unfortunately, legal aspects of patient care. In this chapter, the authors present their perspective on the correction of the anatomic concerns. The larger task of forming a positive physician–patient relationship is one that we all continue to learn together, ideally with prudence, judgment, and humanity.

Etiology

Etiology

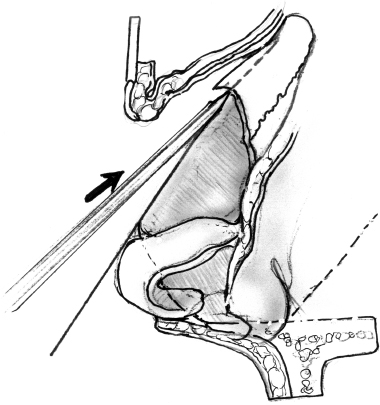

There are several reasons why a patient may have what is judged to be an overresected dorsum after rhinoplasty, as depicted in Fig. 9–1. Technical reasons include the overzealous use of flat osteotomies, the overuse of rasps, or the overuse of saws. Rarely, settling occurs during or after rhinoplasty when there has been a weakening of the dorsal support of the nose after septoplasty. When osteotomies are performed, this is a particular concern in the patient who has short nasal bones. In addition, this overresection may occur when the surgeon, in reducing a dorsal hump, is unsuccessful in anticipating that the centerline of the nasal dorsum should be highest at the rhinion to compensate for the thinness of the skin at this location. The recommended angle of the skeletal dorsal contour is depicted in Fig. 9–2. Finally, there can be a “saddling” of the nose from an uncommon, but significant, infection or trauma to the nose after rhinoplasty.

Regardless of the etiology, the resulting flattening of the dorsum that occurs creates a disconjugation of the balance between of the upper vaults and middle vaults of the nose and nasal tip. If the goals of the surgeon in accepting the challenge of revision rhinoplasty are to restore the balance, symmetry, and proportion to the nose, he or she must have a thorough understanding of the pertinent anatomy, dynamics of rhinoplasty, and aesthetics of the nose.1–4

Anatomy

Anatomy

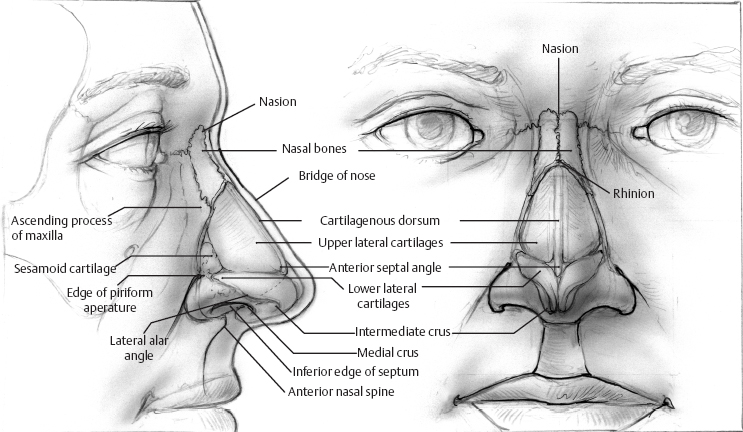

The nasal dorsum is frequently described as having two integrated components: the bony or upper vault and the cartilaginous or middle vault. The upper vault is formed by the nasal paired nasal bones that articulate along their medial edges with each other and along their lateral edges with the frontal processes of the maxilla. Superiorly, the nasal bones each articulate with the nasal process of the frontal bone.

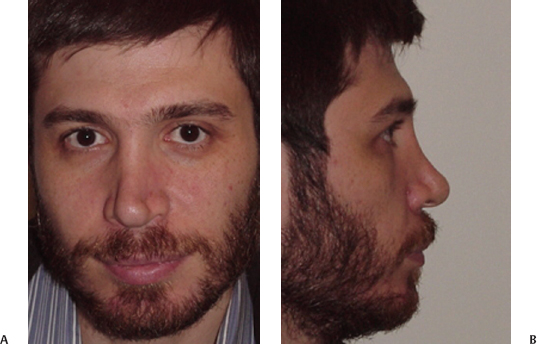

Figure 9–1 (A) Frontal and (B) lateral photographs of patient with overresected dorsum revealing lack of dimension in upper midface, inverted “V” suggestion, and appearance that nose is in “two compartments.”

The upper lateral cartilages form the structure of the middle nasal vault. The upper lateral cartilages underlay the nasal bones for a distance of 3 to 10 mm; a disruption of this relationship, either traumatically or iatrogenically, will lead to a crooked nasal deformity, visible collapse, or airway obstruction. These paired, triangular-shaped cartilages are joined in the midline to the cartilaginous septum for most of their length, separating from the septum only at their caudal margin. The cartilaginous septum continues caudally past the upper lateral cartilages to intercalate with the alar cartilages, finally ending in attachment to the nasal spine of the maxilla (Fig. 9–3).

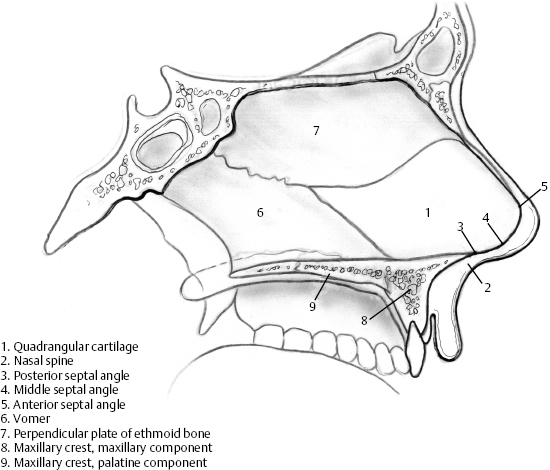

The principal components of bony portion of the nasal septum are the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and the vomer (Fig. 9–4). The perpendicular plate articulates with and bisects the tented-up paired nasal bones and the frontal bone superiorly. Behind this, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone articulates with the cribriform plate. Posterior and posterosuperiorly, the perpendicular plate and vomer extend to reach the sphenoid bone. Inferiorly, the vomer is set in a groove provided by the maxillary crest of the maxilla and the superior aspect of the palatine bone. The perpendicular plate and vomer diverge anteriorly in the midsagittal plane, allowing the quadrangular cartilage of the septum to insinuate between the two via a network of fibrous attachments. The dorsum of the nose derives most of its strength from the midline continuation of the bony and cartilaginous septum. During rhinoplasty and septoplasty, this dorsal support is preserved by the maintenance of adequate caudal and dorsal “struts.” The bony septum actually provides little support for the nasal tip. This is provided instead by the attachments between the tip cartilages and the caudal cartilaginous septum.

Figure 9–3 Drawing depicting skeletonized nasal anatomy revealing relationship of the nasal bones, the upper lateral cartilages, and the lower lateral cartilages.

The nasal tip or caudal third of the nose is shaped by the intricate forms of the lower lateral cartilages, the fibrofatty lateral ala, and the caudal septum and the junctions this compartment makes with the upper lateral cartilages cephalically, the upper lip caudally, and the cheeks laterally. The lower lateral cartilages take origin within the columella, where their medial crural footplates have fibrous attachments to the septum above the nasolabial junction. They curve medially to meet the septum and then quickly flare laterally and cephalically to form the cartilaginous structure of the nasal lobule.

The lower lateral cartilage is divided into three unequal segments, delineated by the two major inflection points in its curvature. Forming the cartilaginous structure of the columella are the narrow medial crura whose caudal outline can be seen externally as the double break of the columella. The intermediate crura depart the sagittal plane of the columella to travel superolaterally. At a point recognized externally as the tip-defining points of the lobule, the lower lateral cartilages rapidly expand in width as they flare cephalically and laterally toward the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilages, with which they have a variable relationship.

Several anatomic features and structures provide tip support for maintenance of the tip position. The major tip support mechanisms include the intrinsic strength of the lower lateral cartilages, the attachments of the medial crural feet to the caudal septum, and the fibrous attachments of the lower lateral cartilages to the upper lateral cartilages. The minor tip support mechanisms include the interdomal/septal angle ligament, the septal dorsum, the attachments of the lateral crura to the pyriform aperture, the attachments of the alar cartilages to the overlying soft tissue, the nasal spine, and the membranous septum. Surgical maneuvers during rhinoplasty disrupt several of these support mechanisms during rhinoplasty and must be reconstituted or mimicked if nasal tip position is to be preserved.5

Given a particular osseocartilaginous skeleton, innumerable permutations of external appearance are possible, depending on the overlying soft tissue covering. Limitations are imposed on the rhinoplasty surgeon by the character of the overlying soft tissues. Beginning at the root of the nose, the nasal skin is rather thick. It begins to thin considerably at the level of the nasofrontal suture and reaches its thinnest point at the level of the rhinion. It then begins to thicken again as one examines the skin toward the lower third of the nose. At the lobule, the skin thickens considerably because of sebaceous glands and fibrofatty changes in the dermis. The thickness of nasal skin along the midline dorsum has many ramifications for the rhinoplasty surgeon. Very thin skin will reveal imperfections and inordinate detail of the osseocartilaginous skeleton, whether native or surgical creations. By contrast, overly thickened skin may forestall efforts to impart definition or deprojection to a nose. Importantly, resection of a dorsal hump must account for the progressive thickening of the skin as the nose progresses caudally, requiring greater resection of the more caudal cartilaginous dorsum compared with the thinly covered bony dorsum in the region of the rhinion (Fig. 9–5).6–9

As one examines the nasal soft tissues from the most superficial to deep, the following structures are noted. The soft tissue elements are the epithelium, the dermis (which contains a variable amount of sebaceous glands, depending on the position along the cephalocaudal continuum), the subcutaneous fat, and finally the subcutaneous musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), which contains all the nasal musculature. In addition, the nasal SMAS separates a superficial and variable deep layer of subcutaneous fat of the nasal soft tissues. Surgical dissection should be in the sub-SMAS plane, because it will minimize bleeding as well as injury to the adjacent structures. (The preferred plane for surgical dissection is in the immediate supraperichondrial plane over the upper and lower lateral cartilages and the subperiosteal plane over the bony dorsum).

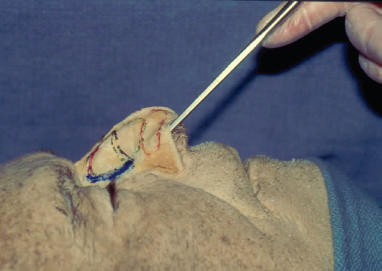

Figure 9–5 Photograph of a cadaver specimen in which the overlying skin has been removed in a sagittal orientation to reveal the differences in the thickness of the skin from region to region in the nose. Note that the skin is the thinnest overlying the rhinion.

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

Aesthetic Anatomic Analysis of Face and Nose

The face and the nose are ascertained by their recognizable patterns of light and shadows, subtle convexities, and concavities that are imparted by the form inherent in the combination of the soft tissue cover as influenced by the underlying skeleton. These units of form, or aesthetic subunits, are fairly consistent from person to person. The relative proportion, form of these subunits, and their general balance with the rest of the face determine whether one’s nose is small, large, asymmetric, or attractive. The aesthetic subunits of the nose typically described are the nasal dorsum, nasal tip, columella, paired lateral nasal sidewalls, alar lobules, and alar facets. The preservation or recreation of these elemental subunits as distinct, individual anatomic entities is essential to provide an optimal nasal appearance that “blends” and is congruent with the rest of the face.

The nose projects anteroinferiorly from the forehead from a point just inferior to the glabella, a flattening or depression in the central forehead. Clinically, this junction forms a relationship between the forehead and the nasal dorsum known as the nasofrontal angle. With the eyes in forward gaze, the nasofrontal angle should lie between the superior lash line and the supratarsal crease.

Underlying this junction is the suture line between the frontal bone and paired nasal bones, radiographically identified as the nasion or clinically as the radix. The rhinion, conversely, is the anatomic or radiographic landmark that indicates the junction of the bony and cartilaginous dorsum. This feature can be appreciated clinically by palpation. On profile, the nasal dorsum precedes anteroinferiorly from the nasion toward the nasal tip in a straight or slightly convex fashion. Ideally, the point of transition from nasal dorsum to nasal tip is recognized as a distinct change in the contour of the dorsum. The change in contour is known as the supratip break (Fig. 9–6).10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree