Chapter 17 Managing Pediatric and Neonatal Abdominal Wall Defects ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

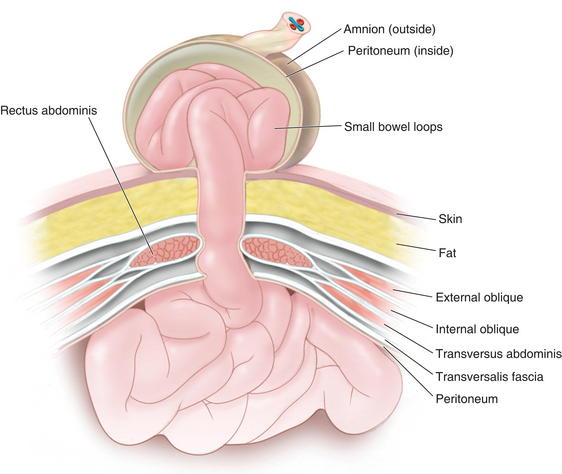

In a patient with an omphalocele (also known as exomphalos) (Fig.17-1), the bowel and viscera, covered by a membrane composed of visceral peritoneum, Wharton jelly, and amnion, herniate through a central defect (≥4 cm) at the umbilical ring. The viscera extend into the base of the umbilical cord and the umbilical cord inserts into the apex of the omphalocele sac. The sac may contain loops of small bowel, large intestine, stomach, and liver (in 50% of cases). These viscera are otherwise functionally normal.

In a patient with an omphalocele (also known as exomphalos) (Fig.17-1), the bowel and viscera, covered by a membrane composed of visceral peritoneum, Wharton jelly, and amnion, herniate through a central defect (≥4 cm) at the umbilical ring. The viscera extend into the base of the umbilical cord and the umbilical cord inserts into the apex of the omphalocele sac. The sac may contain loops of small bowel, large intestine, stomach, and liver (in 50% of cases). These viscera are otherwise functionally normal. Omphalocele is a congenital abnormality and is often associated with other anomalies and syndromes in 60% to 70% of cases. These include Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Cantrell pentalogy, exstrophy of the bladder/cloaca, and chromosomal trisomies such as Down syndrome. The most common anomalies discovered are cardiac and gastrointestinal.

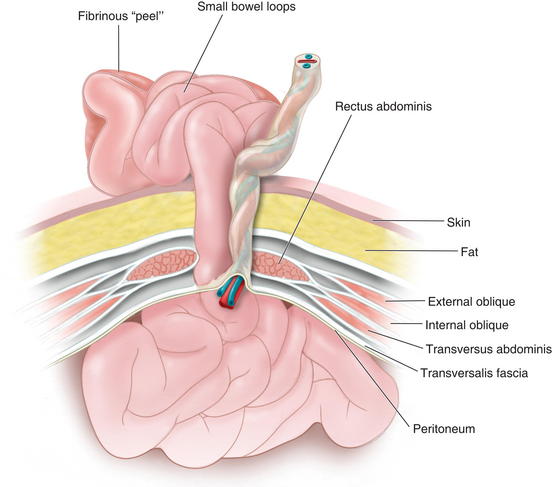

Omphalocele is a congenital abnormality and is often associated with other anomalies and syndromes in 60% to 70% of cases. These include Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Cantrell pentalogy, exstrophy of the bladder/cloaca, and chromosomal trisomies such as Down syndrome. The most common anomalies discovered are cardiac and gastrointestinal. In patients with gastroschisis (Fig.17-2), the small bowel freely protrudes, without an overlying sac, through a smaller defect (<4 cm) at the junction between the umbilicus and the skin. The defect is almost always to the right of the umbilicus. The herniated contents may include small bowel, stomach, bladder, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and testes.

In patients with gastroschisis (Fig.17-2), the small bowel freely protrudes, without an overlying sac, through a smaller defect (<4 cm) at the junction between the umbilicus and the skin. The defect is almost always to the right of the umbilicus. The herniated contents may include small bowel, stomach, bladder, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and testes. Unlike omphalocele, gastroschisis is not congenital. It is thought to be related to an in utero vascular accident. For that reason, gastroschisis is associated with small bowel atresias, which also are believed to be caused by in utero vascular accidents.

Unlike omphalocele, gastroschisis is not congenital. It is thought to be related to an in utero vascular accident. For that reason, gastroschisis is associated with small bowel atresias, which also are believed to be caused by in utero vascular accidents. Both omphalocele and gastroschisis are associated with intestinal malrotation, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis are associated with intestinal malrotation, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). The incidence of omphalocele is 1 in 5000 live births while that of gastroschisis is 1 in 2500 live births. Furthermore, mothers of infants with omphalocele are, on average, 10 years older than those with gastroschisis.

The incidence of omphalocele is 1 in 5000 live births while that of gastroschisis is 1 in 2500 live births. Furthermore, mothers of infants with omphalocele are, on average, 10 years older than those with gastroschisis. It is important to differentiate a ruptured omphalocele sac, which occurs in 10% to 18% of patients with omphalocele, from gastroschisis because this distinction may affect clinical management. Although the initial treatment for these two entities is the same, the search for other associated conditions is affected.

It is important to differentiate a ruptured omphalocele sac, which occurs in 10% to 18% of patients with omphalocele, from gastroschisis because this distinction may affect clinical management. Although the initial treatment for these two entities is the same, the search for other associated conditions is affected. In gastroschisis, due to exposure to amniotic fluid and compromised blood supply, the small bowel may become thick, shortened, edematous, discolored, and covered with fibrinous exudates (also known as a “peel”). This may reduce the malleability of the bowel and make manual reduction more difficult. Furthermore, extensive peel is thought to lead to a prolonged ileus after bowel reduction.

In gastroschisis, due to exposure to amniotic fluid and compromised blood supply, the small bowel may become thick, shortened, edematous, discolored, and covered with fibrinous exudates (also known as a “peel”). This may reduce the malleability of the bowel and make manual reduction more difficult. Furthermore, extensive peel is thought to lead to a prolonged ileus after bowel reduction. Omphalocele is due to the primary failure of the developing intestines to return to the abdominal cavity after migration into the umbilical cord during weeks 6 to 12 of gestation. Figure 17-3 depicts a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in omphalocele. The abdominal muscles are otherwise normally developed.

Omphalocele is due to the primary failure of the developing intestines to return to the abdominal cavity after migration into the umbilical cord during weeks 6 to 12 of gestation. Figure 17-3 depicts a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in omphalocele. The abdominal muscles are otherwise normally developed. Gastroschisis is believed to be caused by involution of the right umbilical vein during the fourth week of development. The resulting ischemia leads to a full-thickness defect in the musculature of the abdominal wall. Figure 17-4 shows a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in gastroschisis.

Gastroschisis is believed to be caused by involution of the right umbilical vein during the fourth week of development. The resulting ischemia leads to a full-thickness defect in the musculature of the abdominal wall. Figure 17-4 shows a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in gastroschisis.2 Preoperative Considerations

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis may be suspected prenatally with an elevated maternal serum α-fetoprotein (although this level can be normal or elevated because of other conditions) and can be diagnosed readily by prenatal ultrasonography in 75% to 80% of cases (after 14 weeks’ gestation when the fetal midgut returns to the abdomen). They can be differentiated sonographically by the presence of a sac, location of the defect, and presence of additional abnormalities. These methods have increasingly led to detection before birth and allow for prenatal education and family counseling.

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis may be suspected prenatally with an elevated maternal serum α-fetoprotein (although this level can be normal or elevated because of other conditions) and can be diagnosed readily by prenatal ultrasonography in 75% to 80% of cases (after 14 weeks’ gestation when the fetal midgut returns to the abdomen). They can be differentiated sonographically by the presence of a sac, location of the defect, and presence of additional abnormalities. These methods have increasingly led to detection before birth and allow for prenatal education and family counseling. If an omphalocele is discovered, it is important to search for associated anomalies by performing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for karyotype analysis, as well as fetal echocardiography to find structural abnormalities.

If an omphalocele is discovered, it is important to search for associated anomalies by performing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for karyotype analysis, as well as fetal echocardiography to find structural abnormalities. Steps are taken to stabilize the infant immediately following birth. A careful assessment of the oxygenation and ventilation is done because of an association with pulmonary hypoplasia, and the child is intubated if in respiratory distress. A nasogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. The patient is placed on the right side to preserve bowel perfusion. The sac is covered with moist gauze and plastic wrap. Care must be taken when handling the viscera because too much pressure can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and mishandling of the intestines can lead to volvulus. These infants are often hypovolemic and are given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation resulting from both evaporative and third-space fluid losses. With gastroschisis (or ruptured omphalocele) prophylactic broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are administered. Temperature is controlled with a heating lamp. Routine blood work is ordered and a detailed physical exam is performed.

Steps are taken to stabilize the infant immediately following birth. A careful assessment of the oxygenation and ventilation is done because of an association with pulmonary hypoplasia, and the child is intubated if in respiratory distress. A nasogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. The patient is placed on the right side to preserve bowel perfusion. The sac is covered with moist gauze and plastic wrap. Care must be taken when handling the viscera because too much pressure can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and mishandling of the intestines can lead to volvulus. These infants are often hypovolemic and are given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation resulting from both evaporative and third-space fluid losses. With gastroschisis (or ruptured omphalocele) prophylactic broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are administered. Temperature is controlled with a heating lamp. Routine blood work is ordered and a detailed physical exam is performed.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree