The alar base is a crucial yet oftentimes mishandled region during primary rhinoplasty. Surgical manipulation of other areas of the nose can profoundly affect the aesthetic and functional anatomy of the base. Although some alar base defects are the result of neglect during rhinoplasty, more often the problems are secondary to overaggressive treatment. Abnormalities of width, height, contour, and proportion are frequently encountered, and revision techniques are required for correction. We present methods of nasal analysis, indications for surgery, types of alar base defects, and variable techniques for restoration and improvement of individual nasal base components. Multiple case examples will be presented, and chapter pearls are offered as highlights of the material.

Anatomy and Aesthetic Analysis

Anatomy and Aesthetic Analysis

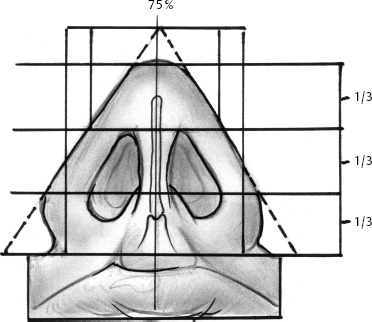

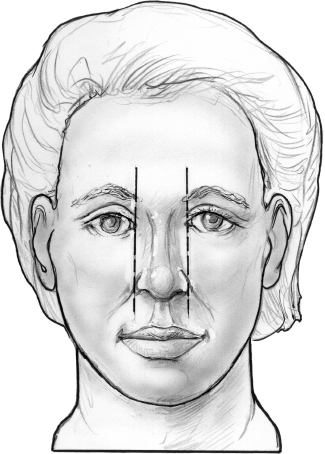

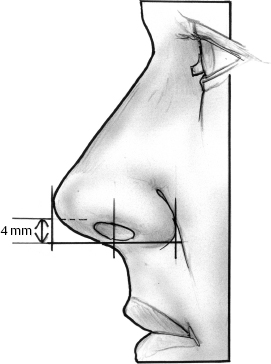

The anatomic constituents of the alar base are the infratip lobule superiorly, the nasal alae laterally, the columella centrally, and the nasal sills inferiorly, bounded by the junction of the alae and the columella with the upper lip. From the basal view, the area should resemble an equilateral triangle, with a columella-to-lobule length ratio of 2:1.1 The width of the infratip lobule should be approximately75% of the basal width. (Fig. 11–1) The nares have an overall ovoid shape, angled 45 to 60 degrees to the long axis.1 The widest portion of the nostril should be closest to the sill, and the overall length of the nare should be approximately two thirds that of the columella. From the frontal view, the width of the nasal base ascribes to the “rule of fifths,” with the distance between alae equal to the intercanthal distance. The nares should be just perceptible in neutral pose, with the columella slightly inferior and parallel to the alae. Overall, a pleasant “gull in flight” silhouette is attributed to the ideal nasal base (Fig. 11–2).1 From the lateral view, the distance from the alar crease to the midpoint of the naris equals the distance from the midpoint to nasal tip.2 Approximately 2 to 4 mm of columella should be evident below the alar rim,3 with some authors supporting 3 to 5 mm of columellar show as acceptable (Fig. 11–3).1,2

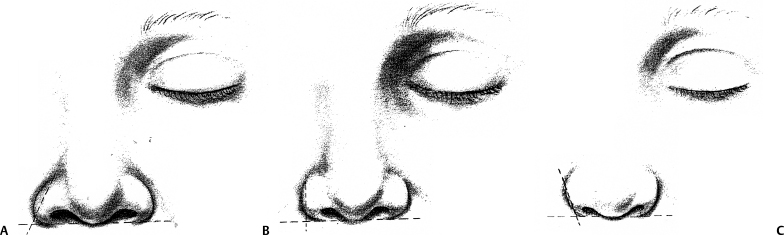

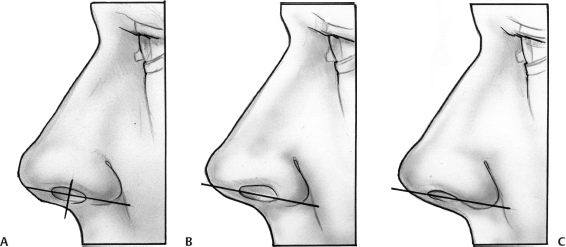

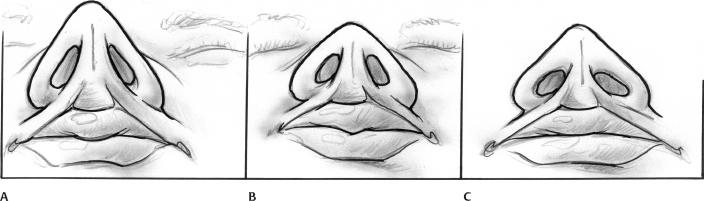

Keeping the these ideal geometric proportions in mind, a detailed and critical analysis of the nasal base may be performed on each patient. Special attention should be paid to the relationship of the alae to the columella in both the vertical and horizontal axes. Alar flare refers to the maximum degree of convex bowing of the alar base above the alar crease.4 Sheen and Sheen described the alar axis with analysis of the relationship between the vertical plane of the alar lobule to the horizontal plane of the nasal base.5 When seen from the frontal view, the orientation of the alae can be categorized as divergent (flared), straight, or convergent (acute) (Fig. 11–4). They believed extreme lateral divergence would benefit from medial repositioning of the nostril, whereas perpendicular or acute nostrils were poor candidates for alar resections, resulting in a pinched or “bowling pin” look.5 Seen from the lateral view, the position of the alae and columella should be carefully evaluated. Gunter et al. formulated a method of analysis whereby a line is drawn through the long axis of the nostril, forming two halves.6 The distance from this line to the alae or columella should be 1 to 2 mm. A longer distance to the ala signifies a notched or retracted alar rim, with a shorter distance representing a hanging or hooded ala (Fig. 11–5).7 Likewise, a greater or lesser distance from the line to the columella points to a hanging or retracted columella respectively. Using this method, there are nine potential anatomic variations in the alar–columellar relationship.8 The insertion point of the alar lobule into the cheek also should be independently evaluated, because a cephalic insertion gives a retracted, flared look and exaggerates columellar show. Likewise, a caudal insertion contributes to hooding and the appearance of a retracted columella.

Once the alar base has been critically evaluated, the surgeon must further decide which specific elements of the region are contributing to any disproportion. For example, is the wide nasal base secondary to flaring of the alae, excessive soft tissue thickness of the alar rim and columella, a result of poor underlying support offered by the caudal septum and nasal spine or a combination of several factors? In addition to the analytical methods mentioned previously, careful attention to the internal and external length of the nares, nostril floor and sill width and shape, nostril aperture size, and length of the lateral sidewall will help reveal the nuances contributing to the appearance of the base.9 Such thorough preoperative evaluation and planning is paramount in rhinoplasty, especially secondary revision rhinoplasty, where the “mistakes of the past” must not be repeated.

Before proceeding, the author must call attention to the natural variation in alar base anatomy seen both among and between different races and ethnicities. Most of the widely accepted nasal proportions espoused in the literature are based on the Caucasian or leptorrhine nose. Mesorrhine and platyrrhine noses tend to have more alar flare, a shorter columella, and thicker soft tissue covering with weaker structural support (Fig. 11–6). Such anatomy must be evaluated cautiously in the preoperative planning stage, because patients may not desire to part with aspects of their nasal anatomy that they relate to their heritage and racial background. Candid discussion between the patient and surgeon, with conciliation of the patient’s desires and realistic surgical goals will help to avoid an unsatisfactory outcome.

Figure 11–2 Frontal view showing the distance between alae equal to the intercanthal distance. A “gull in flight” shape is ascribed to the ideal nasal base.

Figure 11–3 Lateral view demonstrating acceptable amount of columellar show, with the distance from the midpoint of the naris to both the alar crease and nasal tip being equal.

Indications and Contraindications for Surgery

Indications and Contraindications for Surgery

Indications for alar base revision surgery involve abnormalities of nasal form and function. Anatomic disproportion of the regional components can be aesthetically unpleasant, and the patient may desire correction to enhance his or her overall appearance and self-esteem. Equally important is restoration of proper physiological function, because correction of nasal obstruction or external nasal valve collapse can improve a patient’s overall quality of life. Whether the defects were caused by congenital malformation or previous surgical manipulation, equal consideration of proper form and function in revision rhinoplasty can help guide the physician in the preoperative counseling and planning stages.

Figure 11–5 Method of nasal analysis formulated by Gunter et al.6 (A) A line is drawn through the long axis of the nostril on lateral view, forming two equal halves. The distance from the line to the alae or columella should be 1 to 2 mm. (B) A greater distance signifies a notched or retracted alar rim. (C)) A distance less than 1 to 2 mm represents a hanging or hooded ala. (Adapted from Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Friedman RM. Classification and correction of alar-columellar discrepancies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996; 97:643.

Figure 11–6 Natural racial and ethnic variation in alar base anatomy. (A) Caucasian or leptorrhine nose; (B) Asian or mesorrhine nose; (C) African or platyrrhine nose.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Alar base deformities can arise from multiple etiologies, including trauma, congenital malformations, and iatrogenic causes. Surgical intervention for cosmetic or tumor control purposes is often the culprit, with several studies citing previous aesthetic rhinoplasty as the most common source of alar deformities.7,10,11 Alar base abnormalities can involve problems of width, height, contour, and proportion of the anatomic components. Although deformities can arise from neglect of the region during primary rhinoplasty, problems tend to arise more from overzealous manipulation of the area. Each of these situations will be examined in turn.

Alar Base Complications Caused by Errors of Omission in Rhinoplasty

Surgical manipulation of other areas of the nose during primary rhinoplasty can have a profound effect on the alar base. Maneuvers designed to deproject the nasal tip in particular, such as reduction of a high caudal septum or lower lateral cartilage trimming and repositioning, can lead to widening of the nasal base or alar flaring. Inattention to such interrelationships during rhinoplasty can lead to an unsatisfactory result. One of the founding fathers of the operation, Gustave Aufricht, preached such attention to detail in 1943, when he cautioned “Large nostrils, flaring alae, bulging base of the nostril, ill direction of the alae are the most common shortcomings of the corrected nose.”12 Thorough analysis and planning should alert the surgeon to this possibility preoperatively, and the resultant widening or flare recognized during the procedure. Sometimes these factors may go overlooked, however, requiring secondary rhinoplasty to address such issues.

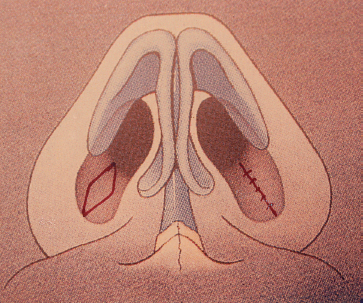

Figure 11–7 Example of alar base incision used for internal nasal floor reduction only. This technique reduces the internal border only and minimally effects alar length and width.

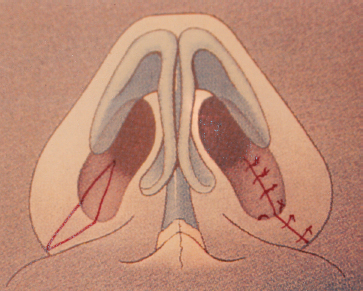

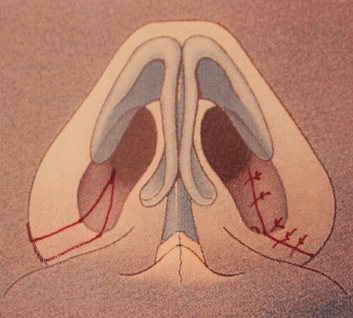

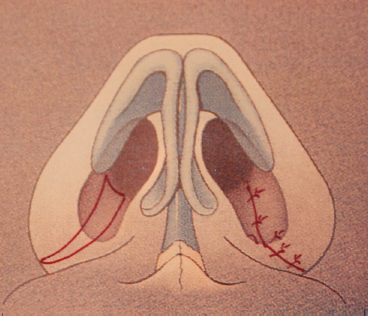

When encountered, the problem of the wide nasal base or alar flaring may be addressed via several techniques. Tissue wedge resections to correct excessive flaring or the bulbous ala were first described by Robert Weir in 1892.13 Since that time, numerous modifications and variations of the so-called “Weir’s Wedge” have been introduced, including contributions from notable rhinoplasty surgeons such as Joseph, Aufricht, Converse, Reese, and Peck.14 Sheen and Sheen championed the “two-surface concept” in alar resections, in which alterations to both the vestibular and cutaneous portions of the nostril must be taken into account. The exact location and design of the incisions will vary depending on the need to correct bulbous alar lobules, large nostrils, or both.5 In general, excisions focusing on the cutaneous or external portion of the ala will correct excessive length, whereas those concentrating on the vestibular or internal region will help to address abundant nostril width. A combination of the two is often needed to correct alar flare or a wide aperture, and examples of different incisions are shown in the figures for instructive purposes (Figs. 11–7 to 11–10).

Figure 11–8 Wedge resection involving the nostril floor, sill, and alar base. This technique achieves a slight decrease in the alar flare.

Figure 11–10 Sliding alar flap allows for maximal reduction with medial repositioning.

Because the alae occupy such a prominent position on the face, any surgical manipulation runs the risk of visible scarring, notching, or an unnatural, “operated” look. Proper incision placement and meticulous soft-tissue closure are essential to minimizing such possible complications. Although some surgeons encourage placement of the inferior arm of the alar wedge incisions right at the alar-facial crease,14–16 the authors believe this can predispose the patient to a blunted alar-facial angle or scar indentation in the very sebaceous skin of the region.17 Placement of the incision just above the crease helps to minimize these complications, while still providing for a smooth, natural contour to the alar-facial and alar-labial junctions. Incisions that cross the ala or sill to incorporate both cutaneous and vestibular skin excisions run an increased risk of notching. Several authors have proposed surgical modifications around the sill or alar rim to help camouflage or eliminate such imperfections.5,14,18 The author advocates a V-plasty technique for incisions that involve both cutaneous and vestibular surfaces to help avoid notching. This calibrated broken-line excision and closure method can be easily incorporated into any incision that crosses the ala or sill (Fig. 11–11; See Figs. 11–24 11–25). Careful intraoperative measuring, marking, and layered wound closure are essential in achieving good results.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree