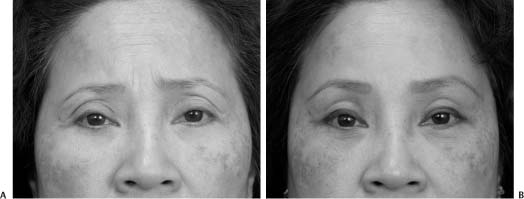

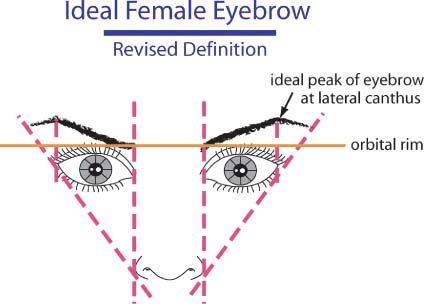

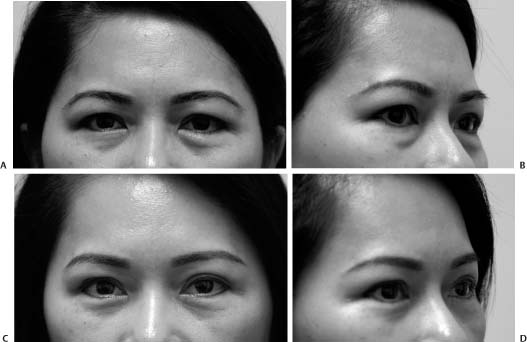

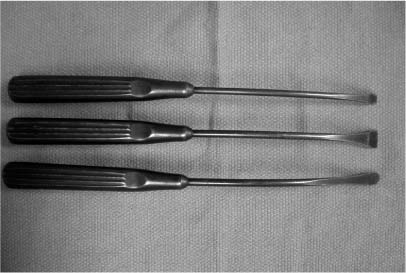

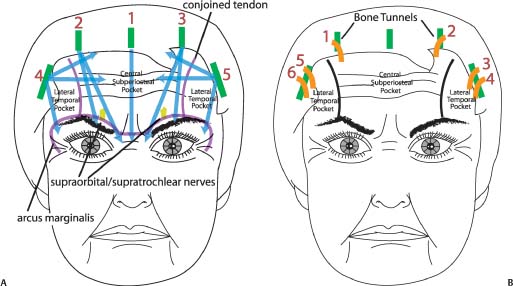

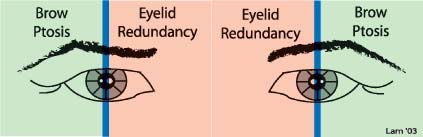

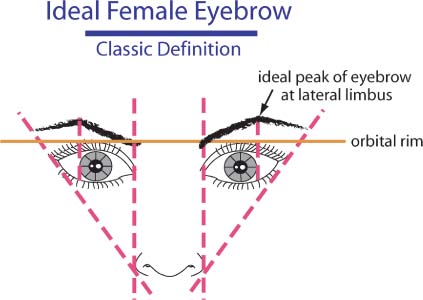

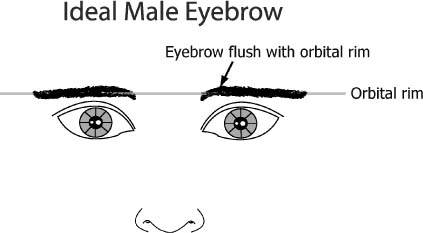

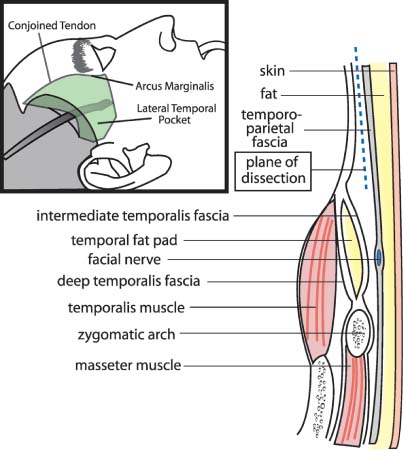

10 Although the Asian face typically does not experience as much aging as that of the lighter-skinned Caucasian, facial rejuvenative surgery is warranted in the majority of Asian patients to varying degrees.1 The darker Asian complexion renders the face more impervious to the ravaging effects of the sun and thereby aids in the preservation of a youthful countenance. Despite relatively fewer fine to coarse rhytids that manifest in the Asian skin, ptosis of facial tissues remains a prevalent condition, especially in the brow/upper-eyelid complex vis-à-vis the lower face and neck. Accordingly, brow lift procedures are a mainstay of intervention for the mature Asian face. Similarly, ablative skin resurfacing is less often necessary and is also less tolerated in the Asian skin (refer to Chapter 14). Because the Asian skin often responds poorly to ablative skin therapy, surgical incisions may also remain conspicuous for an unacceptably protracted period of time. Any incisions in the central aspect of the face should be thoughtfully reviewed with the patient, and every effort should be made to avoid these types of incisions. This chapter will outline a surgical treatment strategy that relies on incisions that are created for maximal camouflage.2 For instance, brow incisions are abbreviated in length and placed behind the hairline. Upper-eyelid incisions for upper-lid blepharoplasty do not extend past the lateral canthus in an area that may be more visually noticeable. Lower-eyelid surgery is performed via a transconjunctival approach so that no external incision will be observed. Face lift incisions are performed in a curvilinear and post-tragal fashion and are hidden high in the postauricular sulcus and hairline. The surgical philosophy and techniques outlined in this chapter are also well suited for other races, as the author relies on the same methodology for all of his patients irrespective of race. The author contends that the brow lift, face lift, and blepharoplasty techniques described herein offer the benefits of a natural rejuvenation and a rapid recovery. Over the past decade, the upper face/brow complex has assumed an increasing role in facial rejuvenation for two principal reasons. First, the advent of the minimally invasive, endoscopic brow technique has revolutionized brow surgery. The patient wary of the larger transverse incision involved with the coronal lift may be more readily accepting of the shorter scars in the hairline that accompany this type of brow lift. However, champions of the coronal or pretrichial lift advocate the more precise brow positioning and better exposure with the these traditional techniques. The direct brow lift, which has fallen into some disrepute in the Western world, may still remain a minimally invasive viable alternative to many Asians in that micropigmentation (eyebrow tattooing or permanent makeup) is much more prevalent in Asians and may effectively camouflage any suboptimal, more visible scarring associated with this technique. However, if micropigmentation is undesirable to the patient, a direct brow lift may yield a very obvious scar in the Asian skin. In the West, the midbrow lift has been used as a mainstay of brow lifting by certain staunch proponents of this technique, who even propose the suitability of midbrow elevation in the younger rhytid-free female population.3 However, the darker complected Asian patient may manifest a fine white incision line, or worse yet a hypertrophic cicatrix, in the very conspicuous midforehead that would otherwise go unnoticed in the more alabaster Caucasian or lighter toned Asian patient. The surgeon now has an unprecedented, wider selection of options for upper facial rejuvenation than ever before: all of these modalities offer unique benefits and drawbacks. Despite the many varied techniques that exist, the author contends that the minimal-incision brow lift offers the best solution for the majority of Asian patients, as this technique avoids obvious incisions on the face (which can be particularly problematic for the Asian patient), does not require any excision of hair, and facilitates a rapid recovery. The second reason that brow rejuvenation has risen in prominence over the past 10 years is the increased comprehension that the scientific community has gained about the importance of the brow in facial aging. In the past, the face lift represented the central method by which the face was restored to a more youthful expression. However, today the brow has caught up and perhaps even exceeded the rejuvenative potential of a rhytidectomy in certain respects. Empirical observation has revealed that the brow may begin to age 10 years before the lower face does in many patients. However, patients may remain oblivious to brow descent and simply complain of looking more tired and aged than they feel. They may come to the facial aesthetic surgeon seeking to recapture their youthful appearance by demanding a blepharoplasty be performed but ignorant that a brow lift may be a more suitable undertaking. This fault may be accorded in part to the mass media, which have erroneously indoctrinated the public into equating tired eyes with eyelid surgery. The author has also noted that Asian patients suffer more frequently from brow descent than lower facial aging, compared with the Caucasian patient, in whom the lower face ages at an equal rate as the upper face. At this point, a simplified algorithm should be introduced that may facilitate easy analysis (but should be used with discretion and judgment). An imaginary vertical line can be drawn through the midpupil. Any tissue ptosis medial to this line may be thought of as upper eyelid in origin and may be corrected with an upper-lid blepharoplasty. Conversely, any ptosis that presents lateral to this invented line may be assumed to be principally due to brow ptosis rather than excessive upper-lid skin (or dermatochalasis) (Fig. 10-1). The fallacy that bedevils many junior surgeons is the same unsophisticated thinking that encumbers patients, namely, that all upper-lid tissue ptosis is a by-product of redundant eyelid skin rather than brow ptosis. Quite the contrary is true: the brow tends to descend chronologically earlier than the onset of upper-eyelid skin redundancy. Anatomic studies have also highlighted the weaker development of the lateral-brow musculature that may serve as the principal cause for more significant lateral-brow ptosis.4–6 If an upper-lid blepharoplasty is performed in lieu of a recommended browplasty, the brow may actually be further depressed; and if excessive upper-lid skin is removed, a brow lift may be precluded in the future due to risk of lagophthalmos (Fig. 10-2A,B). Also, an aggressive upper-lid blepharoplasty alone, especially if the adjacent, thicker brow skin is removed together with the thinner upper-lid skin, may result in an unnatural appearance. The aesthetic position of the brow should always be recalled when considering a brow lift. In the ideal female eyebrow, the eyebrow configuration assumes a tapered contour with a thicker, medial club of the eyebrow narrowing laterally to a fine point. The medial brow should rest at or slightly below the orbital rim, with the peak of the eyebrow situated either at the lateral limbus (classic description, Fig. 10-3) or at the lateral canthus (revised description, Fig. 10-4) lying above the orbital rim. Laterally the eyebrow descends somewhat to end at a point drawn through the imaginary line that joins the alar-facial groove through the lateral limbus or lateral canthus. The descended brow often assumes a more flattened appearance that resembles the ideal male eyebrow, that is, a straight line that runs along the orbital rim (Fig. 10-5). Because the ideal female brow is arched laterally and because the brow descends disproportionately laterally, all efforts to raise the brow position should be concentrated laterally. As will be discussed, all fixation sutures are laterally based, and no medial suspension is undertaken. This surgical technique properly restores the ptotic brow without unnaturally producing a startled or frightened appearance that is a stigma of an improper brow lift (Fig. 10-6A-D). Figure 10-1 An imaginary vertical line can be drawn through the midpupil. Any tissue ptosis medial to this line may be thought of as upper eyelid in origin and may be corrected with an upper-lid blepharoplasty. Conversely, any ptosis that presents lateral to this invented line may be assumed to be principally due to brow ptosis rather than excessive upper-lid skin (or dermatochalasis). (From Lam SM, Chang EW, Rhee JS, Williams EF. Rejuvenation of the periocular region: the unified brow, mid-face, and eyelid complex. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;20:1–9; with permission.) Figure 10-2 (A) This 55-year-old Vietnamese woman underwent upper-eyelid blepharoplasty in Vietnam several years before and is shown with noticeable asymmetry, in which the right upper eyelid is positioned farther down than the left. Manual elevation of her right eyelid showed that the patient could not close her eyelid, whereas she could on the left side; therefore, physical examination confirmed that overzealous upper-eyelid blepharoplasty resulted in notable brow ptosis, right greater than left. Any further upper-eyelid skin removal would exacerbate her tired, worried expression, as the brow would be brought farther down and would also risk lagophthalmos. Brow lift was undertaken with caution to avoid risk of lagophthalmos. (B) The patient underwent a minimal-incision brow lift with removal of right upper-eyelid fat from the medial pocket through a small incision. No upper-eyelid skin was removed. She is shown 3 months after brow lift with some improvement in symmetry and in her tired, worried expression without any lagophthalmos. Figure 10-3 Classic description of the ideal female brow position. The medial brow head starts at or slightly below the level of the orbital rim, arching to a peak at the lateral limbus and tapering laterally to an imaginary point derived from the intersection of two points: the alar-facial groove and the lateral canthus. (From Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Figure 10-4 Revised description of the ideal female brow position. The description of the revised brow configuration matches that of the classic description, except the height (or peak) of the brow should lie above the lateral canthus rather than the lateral limbus. Both descriptions are acceptable alternatives, although some feel that the latter is more ideal given the less “startled” look that this shape imparts. Fashion and style change, so there are no absolutes to these guidelines. (From Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Another fallacy that has ensnared the neophyte surgeon is the thought that the eyebrow (the hairy portion of the brow) is the exclusive aspect of the brow that requires rejuvenation. Instead, the entire lateral brow complex should be viewed as a unit, which includes both the hair-bearing eyebrow and the adjoining soft tissue. As part of the physical assessment, the surgeon should place his or her thumb along the ptotic lateral brow and lift the tissue upwards, carefully observing the improved position of the descended soft tissue and hair-bearing eyebrow. The patient should also be educated about this aesthetic deficit and confronted with the rejuvenated appearance using a mirror while the surgeon gently lifts the ptotic brow. Digital imaging should be used only with patients who have marked brow ptosis, as subtle aging may escape the visual capacity of this technology. Any excessive eyelid skin that remains after appropriate brow elevation may be pinched with forceps or between the surgeon’s fingers to illustrate how a concomitant blepharoplasty would further enhance the intended objective. If the patient, however, desires only an upper-lid blepharoplasty, despite a thoughtful education, the surgeon should plan for a conservative upper-lid skin excision that would not compromise a prospective future brow lift or exacerbate the brow ptosis. A relatively unique problem that may be encountered in the Asian patient is improper micropigmentation: the mature patient who undergoes late micropigmentation may try to compensate for a descended brow by tattooing a higher, peaked eyebrow. After the eyebrow has been tattooed in this fashion, surgical elevation of the descended soft tissue may render this drawn line unnaturally high following a brow lift. Accordingly, judicious eyelid surgery may be required instead, or laser removal of the tattoo should be undertaken before a brow lift is entertained. Figure 10-5 The ideal male brow is heavier than the female counterpart, in terms of the soft-tissue component, the hairy eyebrow itself, and the bony orbital rim. Classically, it should rest along the orbital rim in a flatter, straighter configuration as opposed to the arched shape of the ideal female eyebrow that extends superior to the bony rim. (From Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Figure 10-6 (A,B) This 44-year-old Chinese woman appears tired and worried principally due to her descended brow. The extent of brow hooding is evident by the shadow cast over the upper portion of her eye. Her lower-eyelid pseudoherniation of fat is more readily observed in the close-up oblique view and involves only the medial two fat pockets. (C,D) The patient underwent a minimal-incision brow lift, upper-eyelid blepharoplasty, and transconjunctival lower-eyelid blepharoplasty (of only her medial two lower-eyelid fat pockets with no skin removal). She is shown 3 months postoperatively, and her countenance appears less tired. The brow is elevated only laterally to avoid a startled expression. Also, the amount of brow elevation is minimal to effect a dramatic change in her appearance, as the goal of brow elevation is typically only several millimeters of lift and less often measured in centimeters of elevation. The removal of lower-eyelid fat reveals a more pronounced orbicularis oculi roll near the eyelid margin, which the patient should be aware of as a possible outcome postoperatively. The author feels that the appearance of a prominent orbicularis oculi is evident in all patients regardless of age and does not impart an aged appearance. Accordingly, the orbicularis oculi is almost never excised, as the author relies on a transconjunctival approach for the majority of his operative cases. The advent of the endoscopic brow technique has offered patients brow rejuvenation without any discernible, visible forehead incisions and without the large transverse scalp incision involved with the coronal-type lift. The recovery period is shorter than the coronal brow lift, and the scalp anesthesia is less global and of shorter duration than experienced with the coronal lift. Many surgeons have now evolved the technique such that endoscopic equipment has altogether been abandoned, and instead a so-called smart hand technique is used based on tactile feedback and gentle lifting rather than shearing movements, especially near neurovascular structures.7 A more accurate term that reflects the technique is minimal-incision brow lift rather than endoscopic brow lift, as endoscopes have been eliminated in the technique described herein. Only three types of elevators are used for dissection: a small flat elevator, a large flat elevator, and a round elevator (Fig. 10-7). The author uses this style of brow lift for the vast majority of his operative endeavors. Patients have been receptive to the advantages that this technique offers, and its popularity will certainly continue to gain. Figure 10-7 Three types of elevators are used for dissection: a small flat elevator, a large flat elevator, and a round elevator. The small flat elevator is used to initiate subperiosteal dissection and to complete periosteal release along the arcus marginalis. The large flat elevator is designed to elevate the broad area of periosteum between the incision and the arcus marginalis both quickly and uniformly. The round elevator is used to dissect the lateral, temporal pocket atraumatically to minimize risk of temporal nerve injury. However, the small flat elevator is still used to initiate the dissection in the lateral, temporal pocket a short distance behind the hairline and to achieve final release along the arcus marginalis and the conjoined tendon. All of the elevators have an ebonized finish to minimize reflection off their surface. (From Williams EF, Lam SM. Comprehensive Facial Rejuvenation: A Practical and Systematic Guide to Surgical Management of the Aging Face. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004; with permission.) Figure 10-8 (A) Five standard brow lift incisions are used, with one situated in the midline; two located lateral to the midline in the paramedian position (approximately at the lateral canthus) just posterior to the hairline; and two additional, longer incisions located more temporally, also camouflaged by the hairline and extending over a 4 cm distance above the helical crus and over the temporalis muscle and fascia. Dissection occurs in the subperiosteal plane in the central pocket and below the temporoparietal fascia in the lateral pockets, with careful regard to avoid the supraorbital/supratrochlear neurovascular areas using the “smart hand” technique described in the text. Complete release along the arcus marginalis across the orbital rim and along the conjoined tendon (between the lateral and central pockets) is necessary before suspension can be undertaken. (B) All suspension sutures are placed laterally so as to avoid any unnatural elevation of the medial brow complex. The surgical order of suspension follows the numbers in the diagram. The first two sutures suspend the frontalis to the bone tunnels; then the temporoparietal fascia immediately inferior to the incision is suspended to the temporalis fascia immediately superior to the incision, with two sutures placed on each side. Figure 10-9 Dissection in the lateral temporal pocket is undertaken between the temporalis fascia (deep) and the temporoparietal fascia (superficial) to avoid injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve, which resides above in the substance of the temporoparietal fascia. Figure 10-10 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 1: The midline incision is performed first with a no. 15 Bard-Parker blade. Two folded, moistened 4×4 gauze pads assist in lateral retraction and also to absorb any bleeding that may ensue. Figure 10-11 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 2: The wound is retracted with wide double-pronged hooks, and a monopolar cautery is used to dissect down through the periosteum to facilitate subperiosteal dissection. Any excessive bleeding can also be managed with cautery before continuing. The small sharp peliosteal elevator is used to elevate the periosteum down to arcus marginaus centrally (not shown). Figure 10-12 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 3: The midline incision is closed with surgical staples before continuing with the remaining incisions. Of note, only this incision is closed immediately after dissection, as no suspension sutures need to be placed at this site. Figure 10-13 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 4: After completion of dissection in the midline, subperiosteal pocket, the right paramedian port is approached in the same fashion. As the arcus marginalis is approached near the supraorbital notch, the surgeon should take care to release the periosteum in only a lifting motion so as to avoid neurovascular damage. The photograph shows the elevator tenting up the skin along the arcus marginalis adjacent to the supraorbital notch marked out in gentian violet. Figure 10-14 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 5: The bone-tunnel guidance device is used to guide the drill to create a safe, communicating bone tunnel, which will be used later to suspend the frontalis muscle. Figure 10-15 Minimal-Incision Brow Lift, Step 6: After the bone tunnel has been created, the device that comes with the kit is used to confirm that a communicating bone tunnel has been established. The same device may be used to pull the suture through the bone tunnel. The contralateral, paramedian incision is performed in the same fashion as described for the right side in Figs. 10-13 to 10-15.

Management of the Aging Face: Alternative Approaches

♦ General and Anatomic Considerations

♦ Rejuvenation of the Brow: The Minimal-Incision Brow Lift

Preoperative Remarks

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree