CHAPTER 21 Management of Nerve Entrapment Syndromes

NEURECTOMY AND NERVE BURIAL

Burying the nerve in bone is difficult, because the nerve does not easily stay in position. Two small 2.5-mm unicortical drill holes are made through the fibula perpendicular to each other and about 1 cm apart. The nerve is positioned at one end of the bone tunnel, and the suction is applied to the other drill hole to draw the nerve deep into the hole in the fibula. This drill hole technique seems to be the most effective means of burying the nerve inside the fibula. Once the nerve has been passed into the fibular hole, the epineurium can be sutured onto the periosteum. The ankle should be taken through full dorsiflexion and plantar flexion to ensure that there is no traction on the nerve and that the nerve is freely mobile in the posterior aspect of the limb and encased in the fibula itself (Figure 21-1).

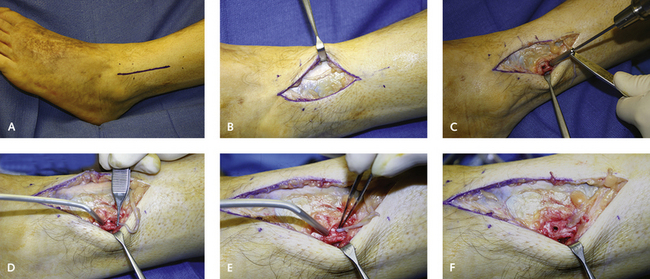

Occasionally, after certain types of injuries, including crush injuries, a neurectomy may not be necessary, and a nerve release after removal of the ligament or tendon may be sufficient (Figures 21-2 to 21-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree