Chapter 12 Management of Metatarsalgia

OSTEOTOMIES FOR METATARSALGIA

Dorsal Wedge Osteotomy

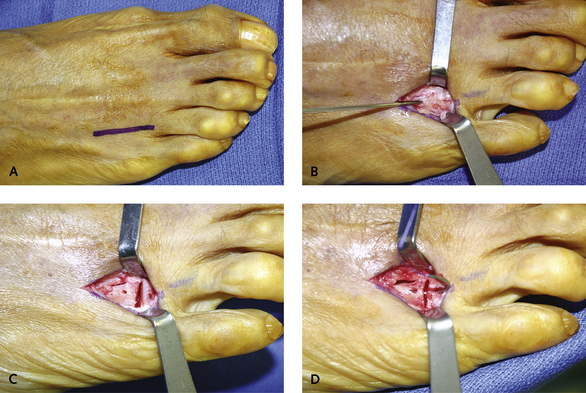

An incision is made over the neck of the metatarsal, and the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal head is visualized. The soft tissues, including the periosteum and extensor tendons, are retracted, and two pilot holes are inserted. These are unicortical holes, made with a 1-mm Kirschner wire (K-wire) and at a 45-degree angle to each other and placed approximately 1 cm apart. The osteotomy is performed in between these pilot holes. Not more than 1 mm of bone must be removed. Accordingly, the actual base of the osteotomy, including the thickness of the saw blade, is approximately 0.5 mm deep. A greenstick cut is performed, and the plantar cortex must be left intact. I prefer to complete the osteotomy with a fracture maneuver that actually opens up the initial cut using manual dorsal pressure on the head of the metatarsal. This maneuver preserves a nice periosteal bridge on the plantar surface, thereby preventing excessive dorsal shift of the metatarsal head. Fixation of the osteotomy is performed with a stout suture of 2-0 absorbable material on a tapered needle, which is easily passed through the predrilled holes. More extensive fixation is not necessary (Figure 12-1). Although I have performed this for more than one metatarsal at a time, multiple dorsal wedge osteotomies need to be carefully planned, because the risk for transfer metatarsalgia increases with the number of these osteotomies performed, and multiple Weil or Maceira osteotomies are preferable.

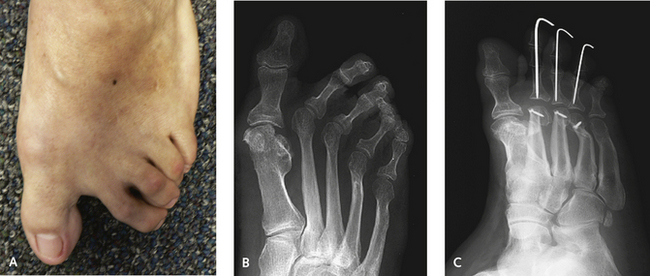

Lengthening of one metatarsal may need to be combined with shortening of another. This is a common problem with brachymetatarsia, in which one or more of the lesser metatarsals are short and metatarsalgia is present on the adjacent metatarsal (Figure 12-2). For these cases of brachymetatarsia, I prefer to use a single-stage lengthening of the involved metatarsals, combined with shortening of the adjacent metatarsals using a Maceira osteotomy. I correct brachymetatarsia according to the age of the patient and the number of metatarsals involved. Although gradual distraction of the metatarsal can be performed successfully, I prefer, wherever possible, to perform a single (nonstaged) lengthening using interpositional graft. This is certainly preferable when more than one metatarsal is involved because the application of distraction to two adjacent lesser metatarsals is impractical. Nonetheless, gradual distraction is a reliable technique, provided it is tolerated by the patient.

If isolated brachymetatarsia is present, correction of the dorsiflexed and extended lesser toe must be performed simultaneously. This operation usually is done with an extensor tendon lengthening and metatarsophalangeal (MP) joint release with percutaneous stabilization of the toe across the MP joint with a K-wire if it is rigid. If the toe is not stabilized at the MP joint, gradual hyperextension of the MP joint may occur with worsening deformity of the toe during lengthening. Lengthening as a single-stage procedure with insertion of structural bone graft has an advantage in that the exact length of the toe can be attained in one setting. The only limiting factor is the actual length that can be obtained without the potential for ischemia of the toe, but I usually am able to obtain approximately 18 mm of length of a single metatarsal without jeopardizing perfusion to the toe. A laminar spreader is inserted while the circulation to the toe is checked as the spreader is gradually distracted. Once the desired length has been attained, then temporary K-wires are inserted in multiple planes across the metatarsals for temporary fixation to keep it out to length with insertion of the graft. The graft can be held secure with a small dorsal plate or with K-wires inserted externally, inserted through the tip of the toe. Function of the toes, however, is good on resolution, and rarely is a flexion contracture of the toe present.

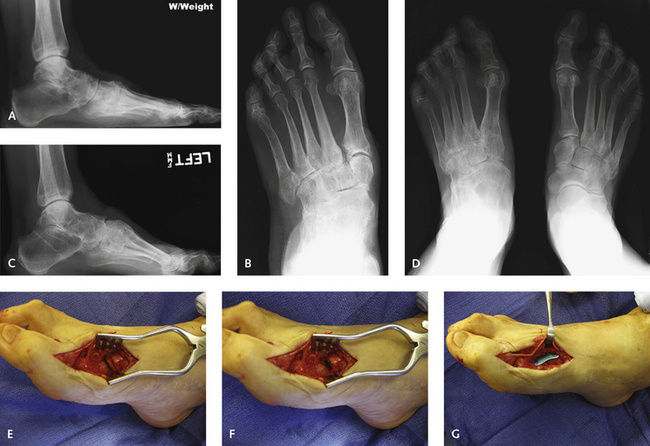

In general, shortening osteotomies of the lesser metatatarsals are very useful to correct diffuse metatarsalgia, particularly that associated with transverse plane deformity of the toes (Figure 12-3). In cases with second metatarsal overload, it is important to identify the source of the increase in the forefoot pressure, and the concept of the metatarsal rocker is very useful. It would be a serious error, for example, to shorten a second metatarsal if the source of the problem was an elevated first metatarsal, particularly if the elevation was from a malunion after fracture or previous surgery. For these cases, instead of trying to correct the overload of the second metatarsal, the first ray must be addressed. This may involve a plantar flexion osteotomy or an arthrodesis of the first tarsometatarsal joint in plantar flexion (Figure 12-4). The plantar flexion osteotomy of the first metatarsal may be performed as an opening wedge with a small bone graft inserted dorsally. Alternatively a dome osteotomy is performed with the saw directed from the medial aspect of the metatarsal, rotating the metatarsal into the corrected position. I do not favor a closing wedge osteotomy performed from the plantar aspect of the metatarsal because this is not as stable. The exact opposite scenario exists with a rigid plantar flexed first metatarsal associated with pain under the sesamoids. Figure 12-5 illustrates a case in which I inadvertently fused the medial column in too much plantar flexion. The patient was a 70-year-old woman who had undergone a triple arthrodesis 20 years previously, with arthritis and deformity of the tarsometatarsal joints developing in combination with abduction deformity of the midfoot. Although an arthrodesis was obtained, with the abduction corrected, the forefoot was now in too much plantar flexion, which was not tolerated, and a dorsal wedge osteotomy of the first metatarsal was required. This was accomplished with a long oblique wedge resection from the dorsal base of the metatarsal (see Figure 12-5, E–G).