Fig. 19.1

True even though asymmetrical gynaecomastia in a 62-year-old man

Fig. 19.2

Pseudo-gynecomastia (lipomastia) in a 50-year-old man, characterised by fat deposition without glandular proliferation

Epidemiology. Gynaecomastia is the most common breast disorder in more than 70–80 % of male breast disorders. The prevalence of gynaecomastia was reported to be between 32 and 65 % [2]. Usually there is a trimodal age distribution [4]: the first peak occurs during infancy, but this condition tends to regress within 3 weeks from the delivery [5]; the second peak occurs during puberty and has a prevalence of 4–69 % [2, 5]; it begins between 12 and 14 years old and usually regresses in 18 months [4]. The last peak occurs in senile age (50–80 years old) and seems to be due to increase adiposity typical of this age [5].

Pathophysiology. Gynaecomastia results from an altered oestrogen-androgen balance, in favour of oestrogen, or also from increased breast sensitivity to a normal circulating oestrogen level. The imbalance is between the stimulatory effect of oestrogens and the inhibitory effect of androgens [2, 5]. Oestrogens induce ductal epithelial hyperplasia, ductal elongation and branching, proliferation of the periductal fibroblasts, and an increased vascularity.

Oestrogen production in males results mainly from the peripheral conversion of androgens (testosterone and androstenedione) to oestradiol and oestrone, which occurs through the action of the aromatase enzyme. Increased oestrogen production from peripheral conversion due to increased activity of aromatase is observed in chronic liver disease, malnutrition, hyperthyroidism, adrenal tumours, and in rare familial gynaecomastia [6].

Less frequently, an increased substrate can occur at the testicular level due to testicular tumours or to ectopic production of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), as is reported with carcinoma of the lung, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and extragonadal germ cell tumours [6]. Rarely, hyperprolactinaemia may lead to gynaecomastia through its effects on the hypothalamus causing central hypogonadism. Prolactin has also been reported to decrease androgen receptors and increase oestrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cells, which can lead to male gynaecomastia [5].

Aetiology. Gynaecomastia can occur as a result of a relative or absolute excess of oestrogens or a relative or absolute decrease in the levels of androgens or their action. An absolute excess of oestrogens might be attributable to administration of exogenous oestrogens or to endogenous overproduction of oestrogens in males. Oestrogens directly stimulate the proliferation of breast tissue, suppress LH secretion (causing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism), and increase serum levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (decreasing levels of free testosterone). Below are briefly described the most frequent causes of gynaecomastia.

Altered serum androgen to oestrogen ratio gather the most common expression of gynaecomastia.

Puberty. Gynaecomastia during puberty is extremely common: up to 70 % of all boys might have breast enlargement during puberty. During early puberty, the testes might secrete more oestradiol than they do after puberty, resulting in a relative oestrogen excess. The marked increase in IGF1 levels during puberty could also contribute to the development of pubertal gynaecomastia [9].

Senile age. The age-related decline in serum levels of testosterone, increasing adiposity (with resultant raised serum levels of leptin and increased aromatisation of androgens to oestrogens), and rising serum levels of SHBG with a consequent decrease in free testosterone levels all contribute to the relative oestrogen excess in ageing men. In addition older men have multiple co-morbidities and take medications that can contribute to the development of gynaecomastia [8].

Refeeding gynaecomastia. Starvation and substantial weight loss cause secondary hypogonadism; return to a normal diet can lead to a ‘second puberty’ with a transient imbalance in the secretion of oestrogen and androgen, which causes transient gynaecomastia.

Renal failure and dialysis. Dialysis-associated gynaecomastia is probably attributable to refeeding of the chronically ill and malnourished patients with renal failure when they are able to expand their diet and their appetite improves after initiating dialysis treatment. Men with chronic kidney disease frequently have low levels of testosterone that are related to both decreased production and increased metabolism of testosterone, and raised serum levels of prolactin are often seen in patients with chronic kidney disease, as a result of decreased renal clearance and increased production of prolactin.

Hepatic cirrhosis. Men with alcoholic liver cirrhosis have increased serum levels of androstenedione (with resulting increased aromatisation to oestrone), raised levels of SHBG (with reduced free testosterone levels), and increased serum levels of progesterone, all of which might contribute to the development of gynaecomastia. In addition hypogonadism and testicular atrophy are common in men with alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Hyperthyroidism. Increased serum levels of SHBG and progesterone, as well as increased aromatisation of androgens to oestrogens, might contribute to gynaecomastia.

Absolute excess of oestrogens:

Administration of exogenous oestrogens

Intentional therapeutic use: therapeutic oestrogens used in prostate cancer treatment and to initiate breast development in male-to-female transgender patients [7]

Unintentional exposure to oestrogens: occupational; dietary (phytoestrogens), alcoholic beverages; dietary supplements (dong quai, supplements contaminated with oestrogens); other factors such as transdermal absorption, antibalding lotions and partner’s vaginal lubricants

Increased endogenous oestrogen production:

Increased secretion of oestrogens: from the testes (Leydig cell tumours, Sertoli cell tumours, stimulation of normal Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin or luteinising hormone) and from the adrenal glands (feminising adrenocortical tumours)

Absolute deficiency of androgens (hypogonadism):

Primary hypogonadism:

Klinefelter syndrome is the most common chromosomal anomaly in men that leads to primary hypogonadism, gynaecomastia, and infertility.

Testicular trauma or testicular radiation.

Cancer chemotherapeutic agents.

Infections (e.g. mumps orchitis, leprosy).

Disorders in enzymes of testosterone biosynthesis: drugs (e.g. ketoconazole, spironolactone, metronidazole) and inherited defects in androgen biosynthesis.

Secondary hypogonadism (pituitary and/or hypothalamic damage from disease, surgery, or radiation).

Decreased androgen action:

Androgen receptor defects

Absent or defective androgen receptors

Expansion of CAG repeats in the androgen receptor gene

Medications or abuse of drugs [8, 10]:

Increased serum levels of oestrogens or oestrogen-like activity

Exposure to exogenous oestrogens (intentional or unintentional)

Increased aromatisation of androgens to oestrogens (androgens, ethanol abuse)

Oestrogen agonist activity (digitoxin)

Decreased serum testosterone levels:

Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (caused by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists/antagonists and possibly HAART therapy for HIV)

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (possible causes: destruction or inhibition of Leydig cells by chemotherapeutic/cytotoxic agents (e.g. alkylating agents, vincristine, methotrexate, nitrosoureas, cisplatin, imatinib) or inhibition of testosterone or DHT biosynthesis by ketoconazole, metronidazole, high doses of spironolactone, or finasteride and dutasteride)

Androgen receptor blockade:

Flutamide, bicalutamide, and enzalutamide

Cimetidine

Marijuana

Spironolactone

Increased serum prolactin levels:

Antipsychotic agents

Metoclopramide

Possibly calcium channel blockers

Less known causes:

Isoniazid

Digoxin

Effective HAART therapy for HIV infection

Human growth hormone

Amiodarone

Calcium channel blockers (e.g. nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem)

Amphetamines

Diazepam

Antidepressants (tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

19.1.2 Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis

Clinical history should include the following: [5, 6]

Age of onset and duration of the condition

Any recent changes in nipple size and any pain or discharge from the nipples

History of parotitis, testicular trauma, and alcohol or drug use

Family history of gynaecomastia

History of sexual dysfunction, infertility, or hypogonadism

Physical examination should include the following [5, 6]:

Examination of the breasts, with attention to volume, area, tissue consistency, surrounding skin redundancy, and areolar size.

Firm (glandular) and soft (fatty) tissue may require testing to differentiate between true gynaecomastia and pseudo-gynaecomastia.

Assessment of any nipple discharge.

The chest wall should be observed for obvious signs of deformity.

The axilla should also be examined for the presence or absence of pathological lymph nodes.

In general, palpable, firm glandular tissue in a concentric mass around the nipple-areolar complex is most consistent with gynaecomastia (Fig. 19.3). Increase in subareolar fat is more likely pseudo-gynaecomastia, whereas hard, immobile masses should be considered breast carcinoma until proven otherwise. Similarly, masses associated with skin changes, nipple retraction, nipple discharge, or enlarged lymph nodes should raise concern for malignancy.

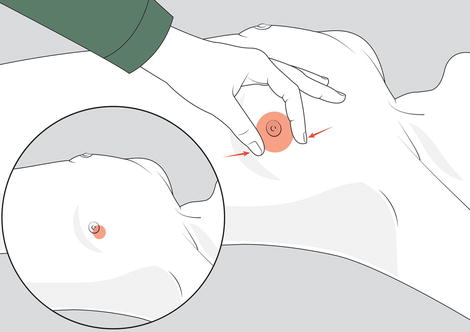

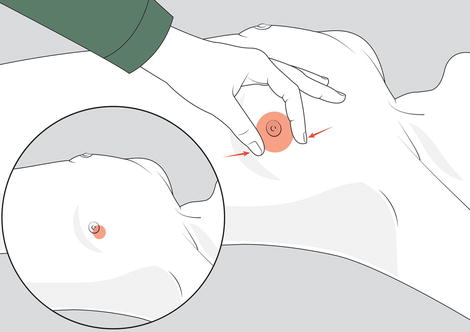

Fig. 19.3

Examination for gynaecomastia. Physical examination method to distinguish gynaecomastia, due to enlargement of the glandular tissue, from pseudo-gynaecomastia, due to excessive adipose tissue. The thumb and forefinger are placed on opposite sides of the enlarged breast and slowly brought together towards the areolar-nipple complex. Gynaecomastia is appreciated as a concentric, rubbery-to-firm disc of tissue, often mobile, located directly beneath the areolar area. Pseudo-gynaecomastia presents no discrete mass. Note that other masses due to disorders such as cancer tend to be eccentrically positioned (insert)

In some cases diagnosis should be extended throughout:

Examination of the testes, with attention to size and consistency, as well as nodules or asymmetry

Observation of any signs of feminisation

Checking for any signs of chronic liver disease, thyroid disease, or renal disease

Patients with diagnosed physiologic gynaecomastia or pseudo-gynaecomastia usually do not require further evaluation. Similarly, asymptomatic and pubertal gynaecomastia do not require further tests and should be re-evaluated in 6 months. Only rare prepubertal (premature) gynaecomastia should be considered for additional testing or close re-evaluation.

Further evaluation is necessary in the following situations:

Breast size greater than 5 cm (macromastia)

A lump that is tender, of recent onset, progressive, or of unknown duration

Suspicious signs of malignancy (hard or non-concentric lump, positive lymph node findings)

Laboratory tests should be ordered using a stepwise approach guided by history and physical examination [5, 6]. Usually tests are not indicated in patients with fatty breast enlargement, physiological pubertal or senile changes, identified drug cause, or clinically obvious cancer. In other cases the following may be considered:

Serum chemistry panel in hepatic and renal failure

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxin levels in hyperthyroidism

Serum concentrations of hCG, luteinising hormone, oestradiol, and free testosterone to differentiate pathologic causes if gynaecomastia is of recent onset, painful, or tender, without liver, adrenal, or testicular abnormalities

Imaging. Mammography is the primary imaging method. It accurately distinguishes between malignant and benign male breast diseases and can differentiate true gynaecomastia from a mass that requires tissue sampling to exclude malignancy, reducing the need for biopsies. In cases of pseudo-gynaecomastia, breast tissue is filled with radiolucent adipose tissue [2, 6]. Breast ultrasound is widely used in the diagnosis of gynaecomastia cases and is more comfortable for male patients. Scrotal USG and abdominal computerised tomography (CT) can also be used to rule out other causes of the disease [3]. If it is not possible to differentiate between gynaecomastia and breast with physical and imaging findings, a percutaneous biopsy should be taken although the number of cells taken in a gynaecomastia biopsy is often insufficient, because gynaecomastia is a predominantly fibrous lesion and this can cause false negative.

19.1.3 Treatment

Before beginning treatment, the patient should be informed that gynaecomastia is often self-limiting. Over time fibrotic tissue replaces the symptomatic proliferation of glandular tissue, meaning that the pain and tenderness will resolve. In pubertal males, 85–90 % of cases regress between 6 m and 2 years, and continuation after the age of 17 is rare.

If a reversible cause of gynaecomastia is suspected (e.g. medications, recreational drugs, occupational exposure to oestrogens, or hyperthyroidism), the medication or source of gynaecomastia should be withdrawn or avoided, respectively, if at all possible. Treatment might be considered in males with symptomatic gynaecomastia or for cosmetic reasons (as breast enlargement can cause considerable social anxiety in many young men).

Nonsurgical treatment. Patient and parent reassurance of the transient and benign nature is often all that is required in the management of most cases of idiopathic gynaecomastia. If the patient has pain or tenderness or experiences embarrassment or distress, a trial of medical therapy should be offered.

In most cases medical management benefits from a high success rate and avoids further surgery. It should be considered that the evidence for the commonly prescribed drugs, tamoxifen and danazol, is based on small non-randomised trials and does not include recurrence rates, optimum dose, length of treatment, or associated long-term risks.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree