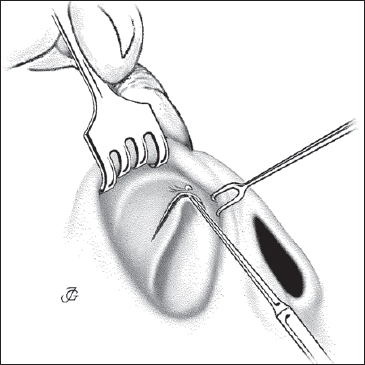

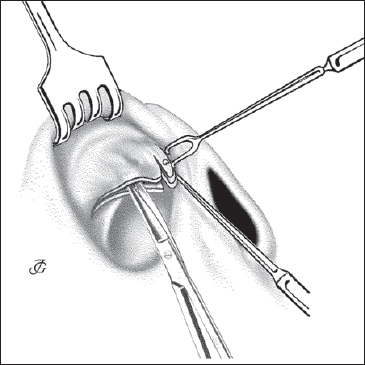

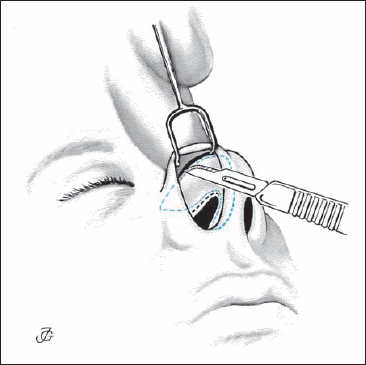

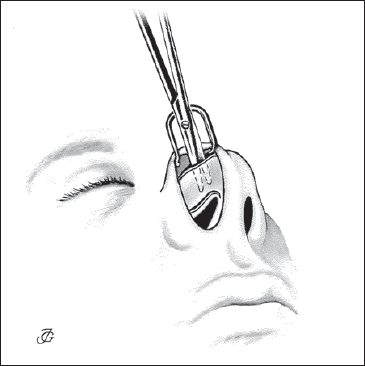

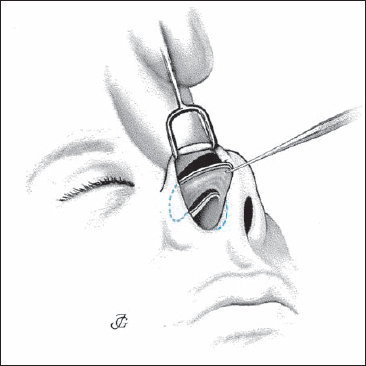

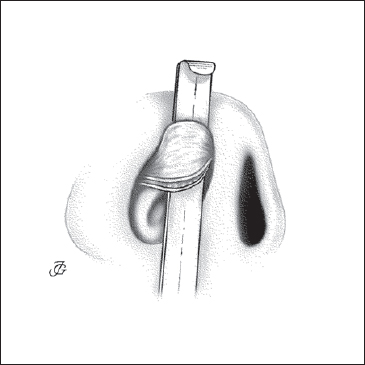

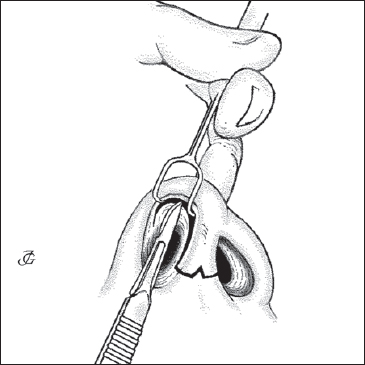

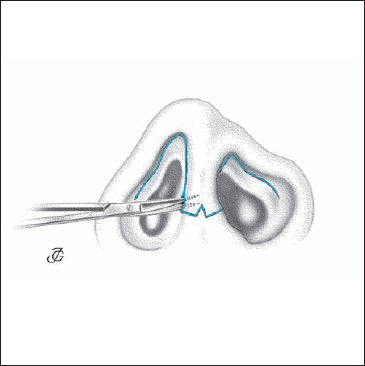

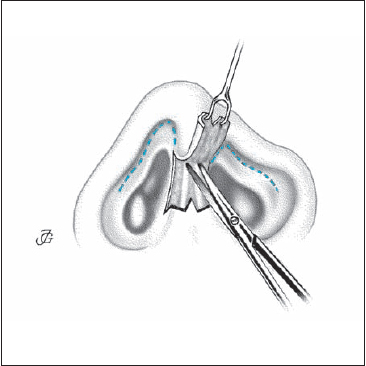

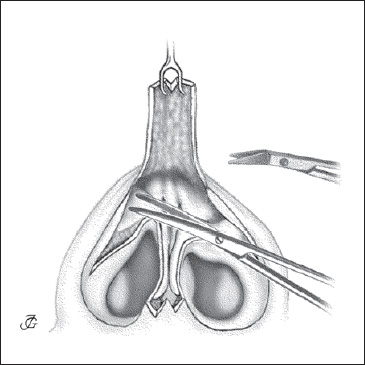

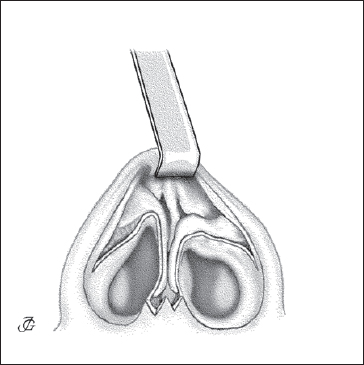

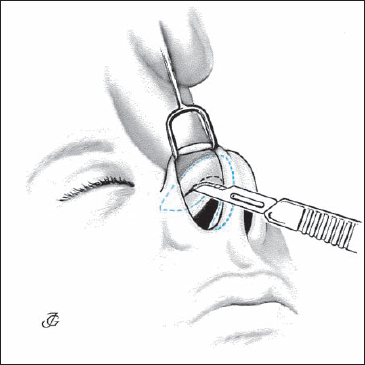

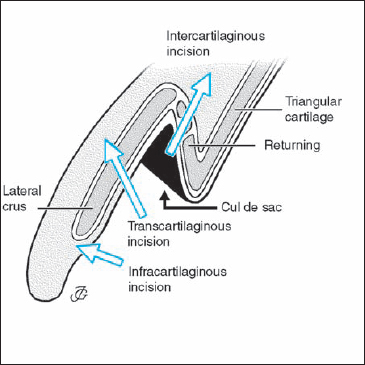

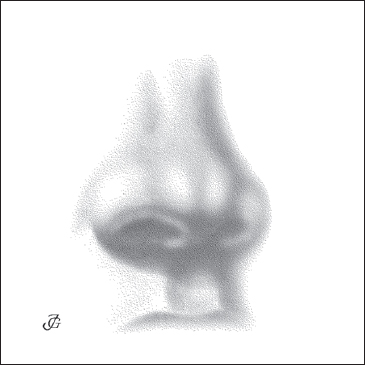

7 Lobular Surgery The lobule and its cartilages can be approached in different ways. There are four generally accepted techniques: 1. retrograde (or inversion) technique; 2. luxation (or delivery) technique; 3. external (or open) approach; and 4. cartilage-splitting (or transcartilaginous) technique. The retrograde and the cartilage-splitting technique are so-called “nondelivery” methods, whereas the luxation technique and the external approach are “delivery” methods. None of these approaches is by definition the best. The choice of method to be used in a given case is based on the type and the degree of the pathology, on the one hand, and the surgeon’s skill and experience on the other(Table 7.1). The retrograde (or inversion) technique is a relatively atraumatic and safe method to address minor deformities and asymmetries of the lobule and the tip. The cranial margin of the lateral crus and dome is inverted through an intercartilaginous incision and exposed into the vestibule. This is always performed bilaterally to avoid postoperative asymmetries. A triangle or strip of cartilage may then be resected from the cranial margin of the lateral crus and dome. The method only allows limited corrections. It is used to refine a broad tip and supratip, to correct minor asymmetries, and to upwardly rotate the tip. The luxation (or delivery) technique is a more traumatic method which allows extensive modification of the lateral crus, dome, and upper part of the medial crus under direct view. The ventral (anterior) side of the lobular cartilage is supraperichondrially mobilized using an intercartilaginous and an infracartilaginous incision. The medial two-thirds of the lateral crus, the dome, and the upper third of the medial crus are then delivered (luxated) outside the nostril. This is always performed on both sides to avoid postoperative asymmetries. In special cases, the lateral crus is completely dissected out and modified (redraped, rotated upward, or resected and reconstructed (see p. 255, 256 and p. 260ff). The luxation method is much more traumatic than the retrograde technique and requires meticulous care in dissecting, modifying, and repositioning the cartilages as well as in closing the incisions. Specific risks are loss of tip support, a drooping tip, and a “polly beak” nose. The technique is the classic way to address the more pronounced abnormalities and asymmetries of the lobule. In the last decades, it has been partially replaced by the external approach. Undermining the lobular skin and exposing the lobular cartilages is done supraperichondrially as close to the perichondrium as possible to avoid damage to the dermis, musculature, and the vascular and nervous supply. The external (or open) approach implies complete exposure of the lobular cartilages, cartilaginous vault, bony dorsum, and overlying soft tissues. It offers also a wide access to the (anterior) septum, anterior nasal spine, and premaxilla. The skin overlying the lobule and the nasal dorsum is elevated via a transcolumellar and two infracartilaginous incisions. The nasal structures are thus more or less “decorticated” or “degloved.” Fig. 7.1 The lobular cartilages are outlined on the skin. The domes are marked. The external approach gives a much wider access to most nasal structures than the two aforementioned endonasal approaches. At the same time, however, it is also the most traumatic of the four methods. Specific risks are a drooping tip and necrosis and scarring of the lower end of the columellar flap. Although the external columellar incision remains visible, it is usually not seen unless looked for. Nowadays, the external approach is the method of choice in patients with more severe deformities and asymmetries of the lobule (e.g. cleft-lip patients, bifid noses) as well as certain revision surgery. It may also be used to reconstruct the anterior septum in patients with a cartilaginous saddle nose. The cartilage-splitting (or transcartilaginous) technique is an endonasal nondelivery method which allows resections from the cranial part of the lateral crus and dome. The vestibular skin and the lateral crus is incised at a distance of about 4–5 mm from the lower margin of the cartilage. The skin overlying the cartilaginous dorsum and lobule is then undermined, and resections can be carried out as necessary. The method does not entail high risk. Too much resection, however, may cause weakness of the lateral nasal wall and inspiratory collapse. Fig. 7.2 The IC incision is continued around the valve angle. The retrograde or inversion technique allows narrowing and upward rotation of the nasal tip. The method requires a bilateral intercartilaginous incision and undermining of the cartilaginous dorsum and the lobule. The modifications that can be achieved by this approach are limited. The procedure is relatively atraumatic and safe, however. The main risk is postoperative asymmetry. Steps Fig. 7.3 The skin over the lateral crura, domes, and interdomal area is undermined in a retrograde direction with a fully curved, blunt scissors. The luxation or delivery technique is the classic way to deal with abnormalities of the lobule, in particular of the tip and alae. The technique was developed in the 1940s and further refined in the 1950s. The lateral crura, domes, and the upper part of the medial crura are dissected on both sides and delivered outside the nostril. To this end, intercartilaginous and infracartilaginous incisions are made bilaterally (Figs. 7.2, 7.6). The cartilages are exposed on a flat instrument (back end of a chisel or a Neivert retractor). The vestibular skin remains attached to cartilage. The lateral crura, domes, and the upper part of the medial crura can now be modified under direct view, as required. One risk specific to the luxation technique is loss of tip support. When wide exposure is required, a columellar strut may be inserted at the end of the operation to preserve support. Fig. 7.4 The dome and lateral crus are pulled caudally and inverted with a round hook that is poked through the cartilage and skin at the cranial margin of the dome. Steps Fig. 7.6 Intercartilaginous and infracartilaginous incisions are made to allow dissection and delivery of the lateral crus, dome, and upper part of the medial crus of the lobular cartilage. Fig. 7.7 The skin over the lateral crura, domes, and upper part of the medial crura is undermined through the infracartilaginous incision. Fig. 7.8 The lateral crus and dome are pulled out with a hook poked through the cartilage and skin at the inferior margin of the dome. The external or open approach is a recently redeveloped method to expose the lobular cartilages, cartilaginous vault, and anterior septum. The method originally dates from the 1920s but was revived and refined in the1980s. Although more traumatic than the previously discussed approaches, the external approach is definitely the method of choice to address the more pronounced deformities of the lobule. The technique has also proven its value in reconstructing the anterior septum, as has been demonstrated by Rettinger (1993). Steps Fig. 7.10 External approach. A transcolumellar inverted-V incision and bilateral infracartilaginous incisions are made using a No. 15 blade. Fig. 7.11b Upward dissection of the columellar skin from the medial crura using small, slightly curved scissors or angulated scissors and a delicate, sharp, two-pronged retractor. Fig. 7.12 The lobular cartilages and the cartilaginous dorsum are exposed supraperichondrially with pointed, slightly curved scissors or angulated scissors. Fig. 7.13 The columellar flap is inverted and retracted with a blunt hook. Historical development of the external approach 1929, 1933: Aurel Réthi (Budapest) introduces a high horizontal columellar incision for surgery of the lobular cartilages, the cartilaginous and bony dorsum, and for inserting a dorsal implant. 1938: EC Padget, very likely unaware of the publications in German by Réthi, describes “cross-cutting the columella and undermining the skin covering the tip and dorsum,” and speaks of an “external exposure.” 1951: H May publishes on “Réthi’s incision.” 1958, 1962: Ante Šerčer (Zagreb) uses a midcolumellar horizontal incision in combination with bilateral endonasal incisions and elevates the skin up to the nasion to correct the nasal pyramid and lobule. He speaks of “decortication of the nose.” 1960, 1966, 1972: Ivo Padovan (pupil and successor of Sercer at Zagreb) and his pupil Jugo (New York), continue using this technique and introduce a V-shaped incision at the columellar base. In 1970 Padovan reports on this approach at the AAFPRS in New York. 1970s: North-American surgeons, especially Anderson (New Orleans), Goodman (Toronto) and Adamson (Toronto), further explore the potentials of the method. 1980s: Although controversial in the beginning, the “external approach” gradually gains worldwide recognition as one of the standard approaches in nasal surgery, also named “open (structure) rhinoplasty.” Fig. 7.15 Intercartilaginous, transcartilaginous, and infracartilaginous incision. In the cartilage-splitting or transcartilaginous technique, the lobule is approached through a bilateral incision of the vestibular skin and the lateral crus (Figs. 7.14, 7.15). This incision is usuallymade at a distance of 4–5 mm from the caudal margin of the lateral crus. A so-called continuous strip of (lateral) cartilage is kept intact. This approach allows resection of a strip from the cranial margin of the lateral crus and dome to narrow a bulbous lobule and tip. At the same time, the tip may be rotated upward. The technique is relatively atraumatic. The level of the incision is of utmost importance. If it is too low, toomuch of the lateral crus will be resected leaving a weak and depressed area which might cause inspiratory obstruction and a pinchednose appearance. Steps Surgery of the nasal tip is an important aspect of rhinoplasty. Most textbooks and instructional courses devote more attention to the surgical modification of this part of the nose than to any other nasal structure. The nasal tip does indeed play a special role in the aesthetics of the human face. This is illustrated by the saying “The one who masters the tip, masters the nose.” Our concept is different. As previously discussed, we feel that the primary task of the nasal surgeon is to restore function by (re)creating normal anatomy and physiology. In this way of thinking, aesthetic improvement takes second place. Its importance to the individual patient should not be underestimated, however. Surgical modification of the nasal tip is almost never related to improvement of function; it is only carried out for aesthetic reasons. The nasal tip may be defined as the most prominent point or area of the external nasal pyramid. It is built up by the domes of the two lobular cartilages, the intradomal soft tissues, and the overlying skin. The nasal tip is defined by the two domes. Ideally they should not be visible as separate structures. On palpation they are usually well distinguishable, however, and they produce a double light reflex (Figs. 7.16a,b). Tip projection, also called tip prominence (or salience), is determined by several factors. In particular, genetic influences (ethnicity, gender), age, trauma, infection, and previous surgery. Tip prominence is high in the prominent, narrow pyramid syndrome and low in the low, wide pyramid syndrome or saddle nose. Tip projection may be related to: According to today’s “beauty standard” for the Caucasian population, tip projection should be less than 0.6 of nasal length. The position of the tip in the vertical and horizontal axis of the face is determined by the above-mentioned factors. If the tip is located more cranial than normal, we speak of an upwardly rotated tip. If it is more caudal than normal, we speak of a low, pendant, or drooping tip. In cases with an upwardly rotated tip, the nasolabial angle is relatively large. If the tip is pendant, this angle is smaller than average. The nasal tip is often compared with a single or a double tripod. The concept of the single tripod was introduced by Günter in 1969 to help understand the effect of certain modifications of the lobule on the position of the tip. In this idea, the two medial crura form the medial leg while the lateral crura form the second and third leg. Others like to compare the tip-supporting structures with a double tripod. In this concept, the medial crus is its short, medial, and almost horizontal leg. The lateral crus forms its lateral and slightly upwardly tilted leg, while its third medial and upward leg is formed by the septum and cartilaginous vault (Fig. 7.19). The medial crura and their neighboring soft tissues are essential in keeping up the tip. The main factors determining the supporting capacity are the rigidity and length of the paracrural connective-tissue fibers, the connective-tissue fibers of the septocrural area, the membranous septum, and the depressor septi muscle. The support provided by the second leg is dependent upon the length and rigidity of the lateral crura and on the connection between the lateral crus and the triangular cartilage. The rigidity and elasticity of the caudal part of the cartilaginous septumis the third factor determining the strength of the tip-supporting tripod. Fig. 7.16a Double light reflex of the tip. Fig. 7.16b Double light reflex of the tip. Fig. 7.17 Projection (prominence, salience) of the tip in relation to the lobular base line. Fig. 7.18 Projection of the nasal tip (t) and prominence of the cartilaginous (c) and bony (b) pyramid in relation to the NBL. Note In contrast to general belief, a recent study has shown that there are no intercrural-running and septocruralrunning fibers or ligaments (Zhai et al. 1995, 1996). Fig. 7.19 Double tripod configuration of tip support. The human nasal tip is subject to a wide array of deformities, abnormalities, and anatomical variations. Whether we are dealing with a deformity is rarely a matter of discussion. Congenital malformations like those in a patient with a cleft lip, nasal hypoplasia, and bifidity are deformities. The same applies to pronounced lesions due to car accidents “bite injuries, or tumor removal. Whether a less pronounced anomaly is to be considered an “abnormality” or a “variation” may be more difficult to decide. This is often a matter of taste. We should keep in mind that several of the variations to be described are to a certain extent race-dependent and therefore have to be considered as normal ethnic variations of the human nose. It is sometimes said that it is the patient who decides whether the nasal tip is abnormal or not. Although understandable, this way of thinking may also be dangerous. It is necessary to warn against surgery that intends to make a normal nasal tip look “more beautiful.” The most common variations and deformities of the nasal tip have already been described and illustrated in Chapter 2 (p. 80ff). In this section we briefly discuss the most common deformities and abnormalities in relation to the most important tip-modifying procedures. Many of the deformities, abnormalities, and variations occur in combination. An amorphous tip is often underprojected at the same time, while an upwardly rotated tip is frequently overprojected. It must be stressed that several variations are race-specific. The tip is not well-defined. This group includes the broad (wide) tip, the bulbous (amorphous) tip, the square tip, and the ball tip. In the broad tip, the domes are far apart. In the bulbous or amorphous tip, they are wide and massive. In the square tip, they are not archshaped but rectangular. In the ball tip, the domes are rounded. It should be stressed that these variations and abnormalities are not solely due to the form and thickness of the cartilage. The thickness of the lobular skin and the subcutaneous soft-tissue layers is another important factor (see Figs. 2.57, 2.58, 2.59). In all these cases, the tip might be given more definition by a narrowing procedure, as required. Function should not be compromised. The continuity of the domes is therefore either respected or reconstructed. The tip is duplicated due to an abnormally large distance between the two domes with an excessive amount of interdomal connective tissue. There is mostly a vertical groove or depression between the domes and in the columella(see Fig. 2.60). This abnormality is usually congenital and the result of incomplete fusion of the two nasal primordia, although it may also be due to previous surgery. This deformity requires dissection and repositioning of the lobular cartilages through an external approach or a delivery technique. The domes are asymmetrical. This may occur as an isolated variation or deformity in combination with bifidityoras part of an asymmetrical lobule (see Fig. 2.61). The projection of the tip is abnormally low compared with that of the cartilaginous and bony pyramid. The tip isnot the most prominent part of the external nasal pyramid; it is depressed and usually more flat. Tip support is mostly diminished (see Fig. 2.63). This abnormality usually requires a complete septorhinoplasty. Depending on the pathology, the anterior septum has to be exorotated or reconstructed. The projection of the domes may be increased by redraping the lobular cartilages or inserting a columellar strut, or by applying a tip or shield graft. The tip is abnormally prominent compared with the projection of the cartilaginous and bony dorsum. The nasolabial angle is mostly decreased (see Fig. 2.62). This condition usually requires a complete septorhinoplasty. The projection of the anterior septum may be reduced, while the projection of the domes may be diminished by redraping the lobular cartilages or by minor resections. The tip is more cranial than normal. An upwardly rotated tip is usually also overprojected. The nasolabial angleis abnormally large (see Fig. 2.64). The tip is more caudal than normal and underprojected at the same time. The nasolabial angle is abnormally small (see Fig. 2.65). A pendant tip is often seen in elderly individuals combined with a long nose. A pendant low tipis also a standard feature of the long, slightly humped Arabic nose. The number of tip-modifying techniques is almost endless. Many of them have proven their value. Some of them bear rather high risks. It is difficult for the beginner to find the right path in the vast literature. First of all, it is important to realize that there is no such thing as the best technique. The type and severity of the deformity, on the one hand, and the skill and experience of the surgeon, on the other, should determine which technique is the most appropriate and safe in a given patient. “It is not so much what you resect but what you leave behind” (Eugene B Kern) The nasal tip and the lobule may be narrowed by: The method to be chosen depends upon the type of pathology, the surgical goals, and the personal preference of the surgeon. Strips and wedges (Figs. 7.20a–c) can be resected from the cranial margin of the lateral crus and dome either by a nondelivery approach (retrograde technique or cartilage-splitting technique) or by a delivery approach (luxation technique or external approach). The retrograde (or inversion) technique is chosen when only a small degree of narrowing is required. The cartilage-splitting technique may be used when a larger resection is planned. The luxation technique has the advantage of working under direct view. The same applies to the external approach. Steps Note

Approaches to the Lobule

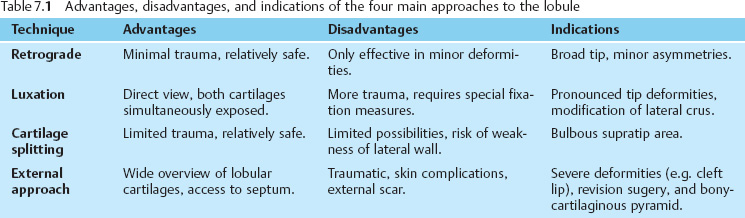

The Four Main Approaches: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Indications

The Four Main Approaches: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Indications

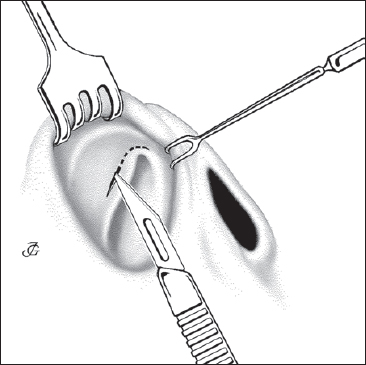

1 Retrograde (or Inversion) Technique

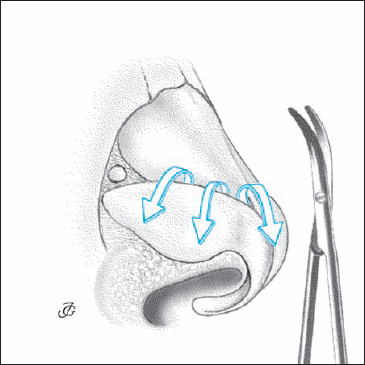

2 Luxation (or Delivery) Technique

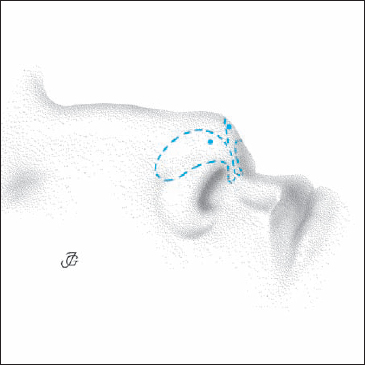

3 External (or Open) Approach

4 Cartilage-Splitting (or Transcartilaginous) Technique

Techniques

Techniques

1 Retrograde (or Inversion) Technique

2 Luxation (or Delivery) Technique

3 External Approach

4 Cartilage-Splitting (or Transcartilaginous) Technique

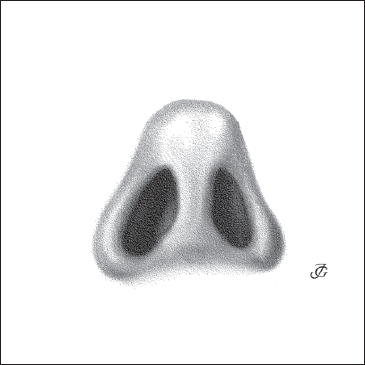

Tip Surgery

Characteristics of the Tip

Characteristics of the Tip

Definition

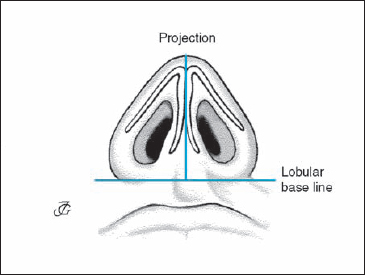

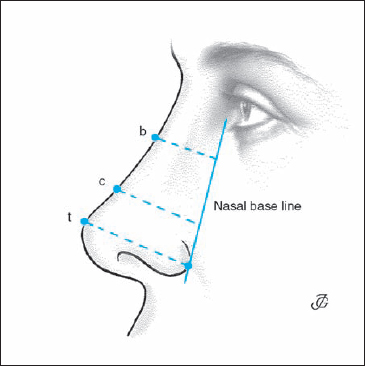

Projection

Position

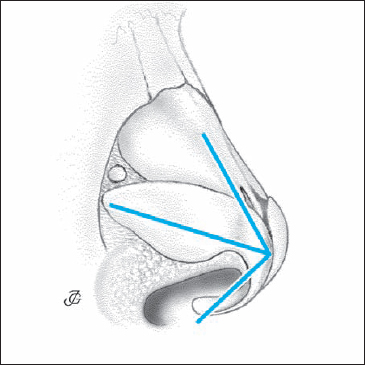

Mechanics of the Tip

Mechanics of the Tip

Deformities, Abnormalities, and Variations of the Tip and Their Surgical Correction

Deformities, Abnormalities, and Variations of the Tip and Their Surgical Correction

Broad, Bulbous (Amorphous), Square, and Ball Tip

Bifid Tip

Asymmetrical Tip

Underprojected Tip

Overprojected Tip

Upwardly Rotated Tip

Hanging (Pendant, Drooping) Tip

Surgical Techniques

Surgical Techniques

Narrowing the Tip and Supratip Area

1 Resecting a Strip and/or Wedge of Cartilage from the Cranial Margin of the Lateral Crus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree