, Madan Ethunandan2 and Tian Ee Seah3

(1)

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Poole, Dorset, UK

(2)

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Southampton NHS Trust Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK

(3)

Orange Aesthetics and Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, Singapore, Singapore

Lips

Subunits and Anatomical Considerations

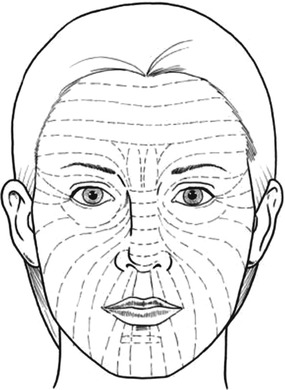

The upper and lower lips have prominent aesthetic and social connotations and form a distinct facial aesthetic unit. The lip unit is defined by the base of the nose superiorly, nasolabial fold laterally and mentolabial fold inferiorly. The lip aesthetic unit can be divided into the cutaneous upper lip, cutaneous lower lip and the vermillion subunits. The upper lip can be further divided into a philtrum and two lateral subunits (Fig. 11.1).

Fig. 11.1

Lip subunits

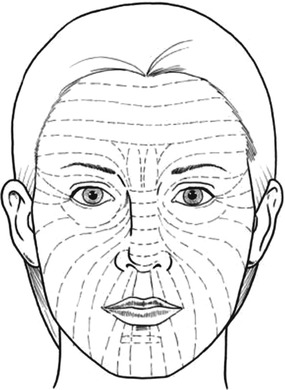

The lip is a composite structure made up of skin, muscle and mucosa. The mucocutaneous junction is defined by the vermillion border and represents a very important facial landmark. The RSTLs are oriented radially around the oral stoma and are vertical in the central region and oblique in the lateral aspects (Fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.2

Orientation of RSTL’s

The labial arteries run in the submucosal plane, along the free lip margins. They lie on the posterior surface of the orbicularis oris and its pulsation can often be felt in this region. The sensory (infraorbital/mental) and motor (facial) nerve supplies are arranged in a radial fashion around the oral stoma.

Lip reconstruction needs to address both aesthetics and function. Satisfactory function requires the presence of intact sensory and motor nerves and restoration of the orbicularis oris muscle sphincter.

Ideally tissue mobilised from within the lip complex provides the best match. Incisions should be placed parallel to the perioral rhytids for simple excisions. It is extremely important not to distort the vermillion border and its precise approximation is mandatory. Flaps mobilised from the adjacent areas should ideally have their incisions along the aesthetic borders (base of the nose, vermillion, nasolabial and mentolabial folds). Consideration should be given to modifying the defect, so as to place the scar in the most advantageous position.

The specific reconstructive options will depend on a multitude of factors, including the presence of full- and partial-thickness defects.

Lower Lip

Skin Only

Primary Closure

Indications

Small defects

Technique

The defect is converted into an ellipse to orient the scar along the perioral rhytids. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and closed in layers.

Tips

Closure of elliptical defects leads to increase in length of the scar and can cause distortion of the vermilion border. This can be overcome by utilising an alternate method of reconstruction or extending the wound into the mucosa and accurately approximating the vermillion border. Consideration should be given to converting the defect into a full-thickness defect to aid closure.

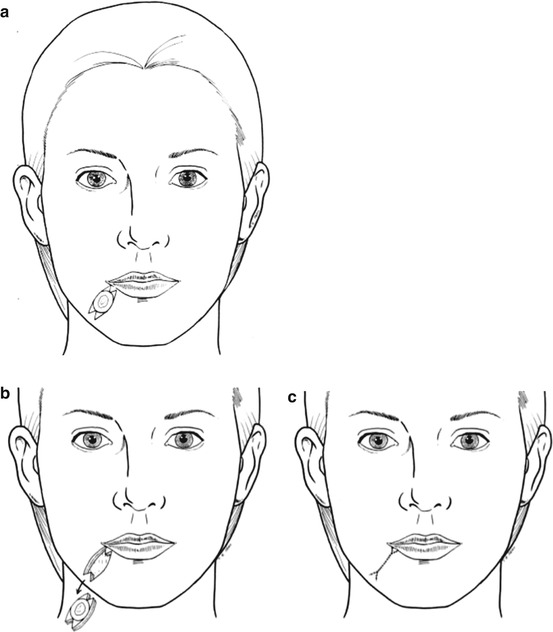

M/W Excision

Indications

Small defects

Technique

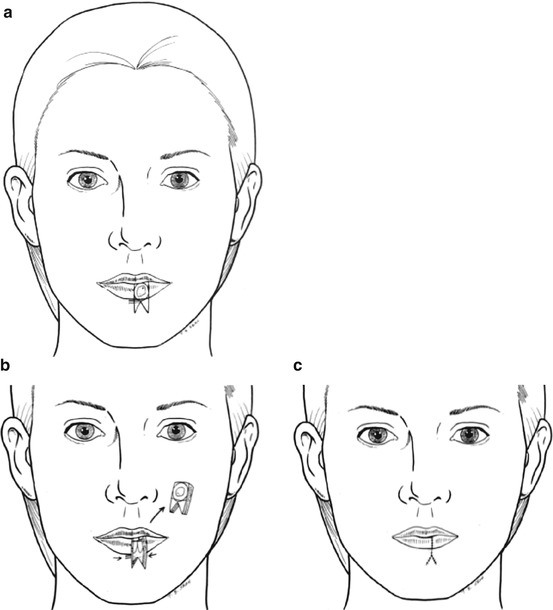

The excision defect is modified to include M/W extremities, instead of an ellipse, to minimise the length of the overall defect. The overall axis of the defect is oriented along the perioral rhytids. The margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and the wound closed in layers (Fig. 11.3a–c).

Fig. 11.3

M/W excision

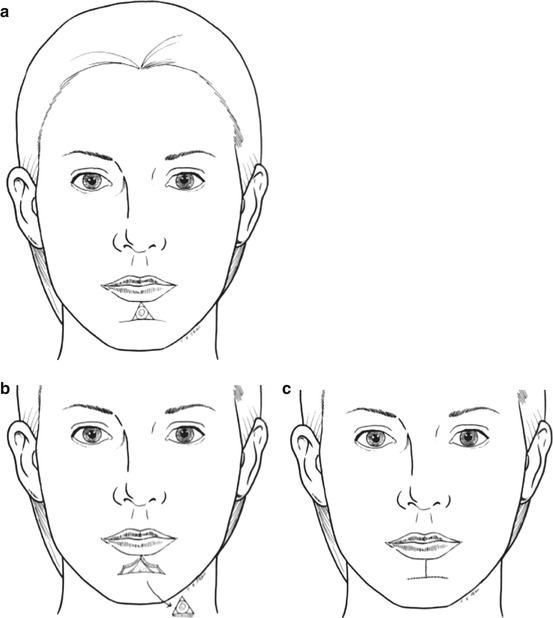

A-T Flap (Close to Mentolabial Fold)

(Horizontal component along mentolabial crease)

Indications

Small defect, defects that could be converted to a triangle

Technique

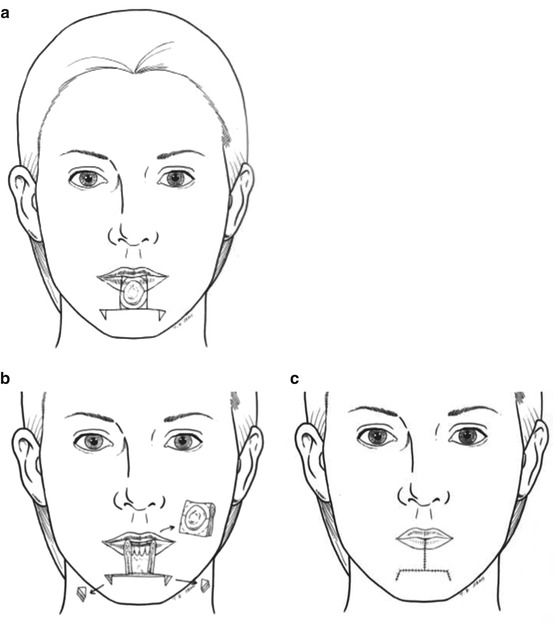

The defect is converted into a triangle, with the base lying on the mentolabial fold. Additional tissue can be removed at the base to facilitate this. Two curvilinear incisions are made from the margins of the base, along the mentolabial fold. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and the defect closed in layers (Fig. 11.4a–c).

Tips

This allows the vertical scar to lie along the perioral rhytids and the horizontal section along the mentolabial fold. Care should be taken, not to distort the vermillion border. Any lengthening or dog-ear that develops along the vertical section of the scar can be corrected by extending it into the mucosal aspect of the lip and accurately approximating the vermillion border.

Fig. 11.4

A-T flap

Superiorly Based Nasolabial Flap

This is a random pattern flap, though it overlies the course of the facial vessels.

Indications

Medium-sized defect of a variety of shapes

Technique

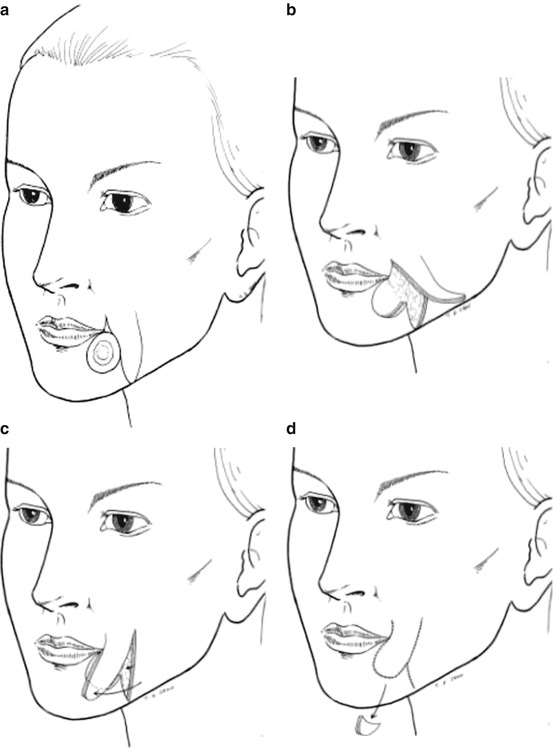

The flap is raised along the nasolabial fold, with one of its margins also forming the margin of the defect. A trial transfer and template can help determine the size of the flap. The overall length of the flap is planned to be longer to accommodate any loss of effective length and the tip triangulated to help primary closure. The base of the flap is designed to be wider than the tip to maintain vascularity. The flap is raised in the subcutaneous plane. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and the wound closed in layers (Fig. 11.5a–d).

Tips

There is a tendency for “pin cushioning” with circular defects and it also makes it difficult to place the scars along RSTL. Consideration should be given to modifying the defect to include parallel margins and extending it to make the final scar lie along aesthetic boundaries and RSTL (see inferiorly based nasolabial flap – Fig. 11.6a–d). The medial dog-ear of the flap can also be excised along the vermillion border for better placement of the scar. The width of the flap should be adequate to prevent displacement of the vermillion.

Fig. 11.5

Superiorly based nasolabial flap

Inferiorly Based Nasolabial Flap

This is a random pattern flap, though it overlies the course of the facial vessels.

Indications

Medium-sized defect of a variety of shapes

Technique

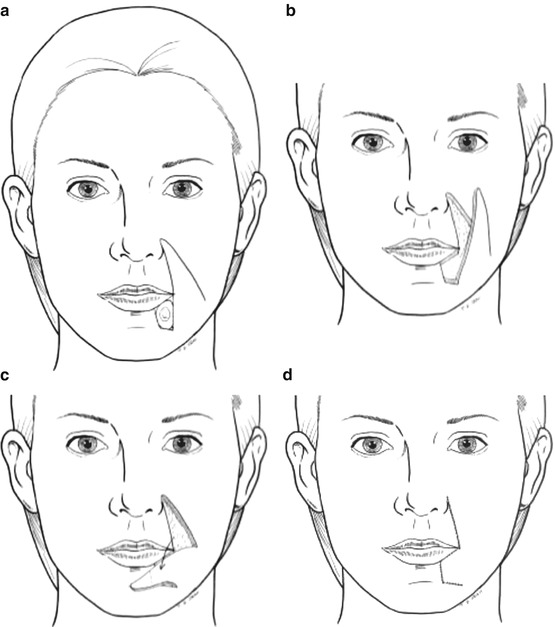

The flap is raised along the nasolabial fold, with one of its margins also forming the margin of the defect. A trial transfer and template can help determine the size of the flap. The overall length of the flap is planned to be longer to accommodate any loss of effective length and the tip triangulated to help primary closure. The base of the flap is designed to be wider than the tip to maintain vascularity. The flap is raised in the subcutaneous plane. The wound margins are undermined in the subcutaneous plane and the wound closed in layers (Fig. 11.6a–d).

Tips

There is a tendency for “pin cushioning” with circular defects and it also makes it difficult to place the scars along RSTL (see superiorly based nasolabial flap – Fig. 11.5a–d). Consideration should be given to modifying the defect to include parallel margins and extending it to make the final scar lie along aesthetic boundaries and RSTL. The medial dog-ear can be excised along the mentolabial crease. The width of the flap should be adequate to prevent displacement of the vermillion.

Fig. 11.6

Inferiorly based nasolabial flap

Mucosa Only

Primary Closure

Indications

Small defects

Technique

The defect is converted to a vertical ellipse and the wound margins minimally undermined and the defect closed in layers.

Tips

Try and avoid “horizontal” incisions to minimise damage to the sensory nerve supply of the lips and distortion of the vermillion border.

Mucosal Advancement Flap

Indications

Large mucosal defects, whole lower lip mucosal defect (lip shave)

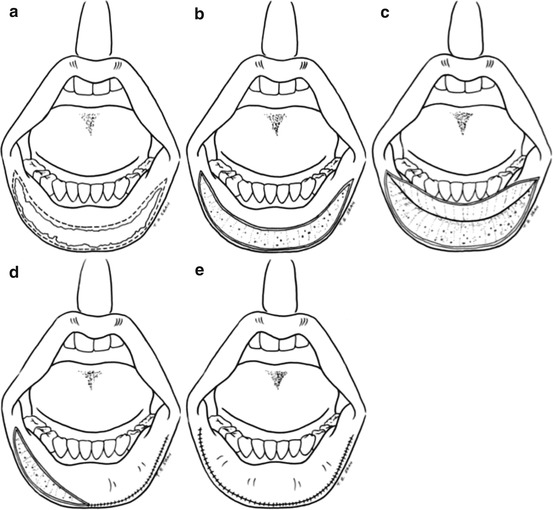

Technique

The margins of the mucosal defect are modified if necessary, to leave even/straight wound edges. The mucosa of the inner surface of the lip is raised as a flap with its base at the labial sulcus. The flap is raised on the surface of the muscle, deep to the plane of the minor salivary glands. This is best done by alternate blunt and sharp dissection, in a vertical direction to create channels, prior to division. Care is taken not to “button hole” the flap. Frequent attempts are made to assess the mobility and adequacy of the flap, and, if possible, the “intervening” tissue is retained between the channels to preserve some sensation. Once adequate mobility is obtained, the flap is sutured accurately to create a new vermillion border (Fig. 11.7a–e).

Tips

There is a tendency for scar contracture to result in a decrease in vermillion exposure. This can be partly accommodated by placing the new vermillion border at a more anterior location. The lateral margins of the defect are frequently narrow, and it is therefore not necessary to dissect widely in this area, which can prevent additional damage to the mental nerves.

Fig. 11.7

Mucosal advancement flap

Full-Thickness Defects

Primary Closure

Indications

Small defects up to 1/3 of the lip

Technique

The lesion is marked with adequate margins and the excision is planned to leave a “shield”-shaped defect, with parallel wound edges superiorly and triangulated margins inferiorly to facilitate primary closure. The axis of the excision is made along the perioral rhytids. The wound is closed in three layers (the mucosa, muscle and skin), taking care to accurately align the vermillion border (Fig. 11.8a–c).

Tips

A simple “wedge/V” excision should be avoided, as this leads to maximum wound tension at the superior margin and a longer scar to accommodate the “V”, without compromising the excision margins. A “shield” excision allows the tension to be evenly distributed across a larger area. Getting an assistant to squeeze the lips during the resection aids control of the labial arteries for haemostasis.

Fig. 11.8

Primary closure

“W” Excision

Indications

Small lesions, up to 1/3 of the lip

Technique

The lesion is marked with adequate margins and the excision is planned to leave a defect with parallel wound edges superiorly and “W” margins inferiorly to facilitate primary closure. The axis of the excision is made along the perioral rhytids. The wound is closed in three layers (the mucosa, muscle and skin), taking care to accurately align the vermillion border (Fig. 11.9a–c).

Tips

A simple “wedge/V” excision should be avoided, as this leads to maximum wound tension at the superior margin and a longer scar to accommodate the “V”, without compromising the excision margins. A “W” excision allows the tension to be evenly distributed across a larger area and importantly the overall length of the scar to be reduced, so that it does not transgress the adjacent aesthetic boundaries. Getting an assistant to squeeze the lips during the resection aids control of the labial arteries for haemostasis.

Fig. 11.9

“W” excision

Bilateral Advancement Flap

Indications

Medium defects

Technique

The defect is modified to have parallel margins. The base is extended, if necessary, to lie on the mentolabial fold. A curvilinear incision is made from the base of the defect, along the mentolabial fold through skin only. The subcutaneous tissues are dissected by alternate blunt and sharp dissection, until sufficient mobility is obtained to achieve primary closure of the defect, without excessive tension. It is often not necessary to make additional relieving incisions along the vestibular sulcus, to facilitate closure. If required, these can often be limited to a fraction of the corresponding skin incision. The wound is closed in three layers (the mucosa, muscle, skin) (Fig. 11.10a–c).

Tips

The blunt dissection of the subcutaneous tissue helps to minimise neurovascular damage to the flap and preserve sensory/motor innervation. The difference in length of the adjacent skin edges along the mentolabial fold can be accommodated by differential suturing or excision of dog-ear along the chin rhytids, inferiorly.

Fig. 11.10

Bilateral advancement flap

Abbe Flap

Indications

Medium-sized defects, away from the commissure. Two-stage flap

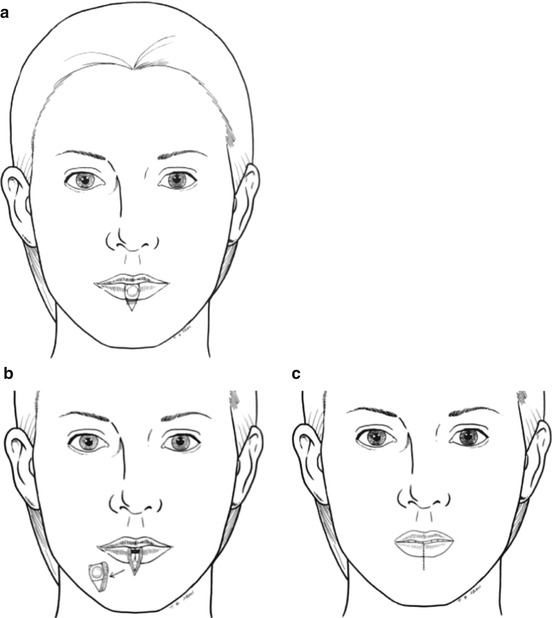

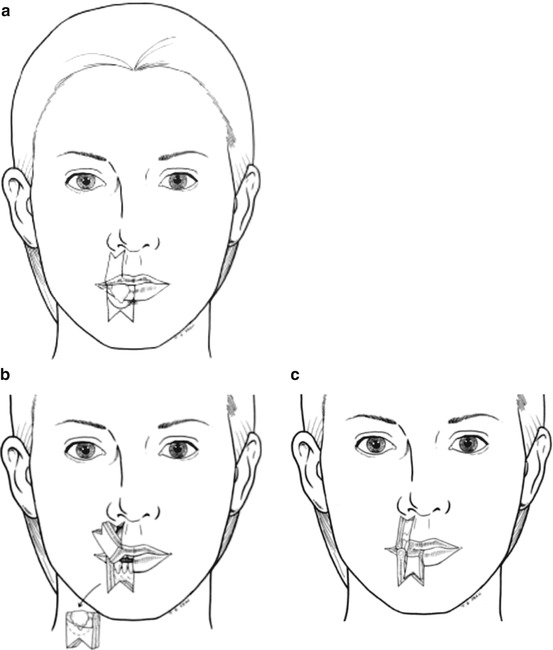

Technique

The defect is modified to have parallel wound edges. The flap is marked to have a similar height of the donor defect, but the width can be reduced by up to 30 %, to make use of the redundancy of the remaining lip. A full-thickness incision is made along one of the borders of the flap (skin, muscle, mucosa), but the incision along the other border is stopped short of the vermillion, to avoid damage to the vascular pedicle (labial artery). The flap is rotated into the defect and the wounds closed in layers, taking care to protect the labial artery (Fig. 11.11a–d). The donor site is closed primarily. The pedicle is divided in 3–4 weeks and any revision to accurately approximate the vermillion border carried out at this stage (Fig. 11.11e).

Tips

Patient compliance is vital and the patient should be counselled appropriately, prior to the procedure. The initial incision on the side of the flap with the vascular pedicle should stop short of the vermillion border. With extreme care, further dissection can be carried out through the skin and part of the muscle, to help accurately approximate the vermillion border during the primary reconstruction. As discussed at the beginning of the chapter, the labial artery runs along the free border of the lip, below the mucosa on the posterior aspect of the orbicularis oris, and maintaining a portion of the muscle above the vessels offers some additional protection. An Abbe flap is better suited for reconstruction of upper lip defects, and other flaps should be considered before deciding on harvesting an Abbe flap from the upper lip to reconstruct a lower lip defect.

Fig. 11.11

Abbe flap

Abbe-Estlander Flap

Indications

Medium-sized defects involving the commissure

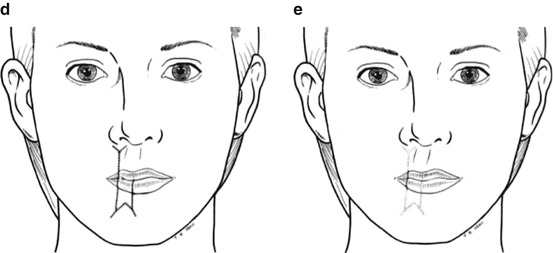

Technique

The flap is marked to have a similar height of the donor defect, but the width can be reduced by up to 30 %, to make use of the redundancy of the remaining lip. A full-thickness incision is made along the lateral border of the flap (skin, muscle, mucosa), but the incision along the medial border is stopped short of the vermillion, to avoid damage to the vascular pedicle (labial artery). The flap is rotated into the defect and the wounds closed in layers, taking care to protect the labial artery (Fig. 11.12a–d). The donor site defect is closed primarily. The intact medial border now forms the new commissure.