CHAPTER 14 Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is the classic, pruritic, chronic dermatosis of the postmenopausal vulva.

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Lichen sclerosus is a common disease, reported in about 3% of incontinent women in a nursing-home environment1. Another survey discovered that 1.7% of women presenting to a gynecologist’s office were found to have lichen sclerosus2. In addition, a vulvar clinic in England found lichen sclerosus to be the most common disease evaluated and treated, occurring in 39% of those patients3. There is a slight familial tendency, but the risk for the development of lichen sclerosus in family members is not known.

Classically, well-developed lichen sclerosus presents as sharply demarcated white plaques encompassing the modified mucous membranes of the vulva, perineal body, and perianal skin (Figure 14.1). Most often, lichen sclerosus begins around the clitoral hood but, despite prominent involvement of the perineal body and perianal skin, it does not generally affect the keratinized, hair-bearing labia majora (Figures 14.2 and 14.3). Distant extragenital disease has been reported in a minority of women. A series of 250 women examined in this author’s office showed 6% with extragenital disease of keratinized skin and no oral or vaginal lesions (abstract still in press; presented at XIX World Congress of International Society for the study of Vulvovaginal Disease, July 2007, Alaska). The most common locations for extragenital disease are upper arms, back, and chest (Figure 14.4). Lichen sclerosus usually, but not always, spares the mucous membrane of the vestibule, and it has been reported only rarely in the mouth4. There is only one report of vaginal lichen sclerosus5. Lesions of the mouth or the vagina suggest an alternative or additional diagnosis.

Although many skin diseases present with white skin on moist mucous membranes or modified mucous membranes, the hallmark of lichen sclerosus is a characteristic texture change of the white plaques. Although the pathognomonic texture change is that of a crinkling or cellophane paper-type appearance, some lesions exhibit a smooth, waxy surface, and others manifest nonspecific irregular, hyperkeratotic white skin (Figures 14.5–14.7). Rubbing and scratching sometimes produce thickening of the skin (lichenification) and superimposed lichen simplex chronicus can obscure diagnostic texture changes of the lesions (Figure 14.8). Fragility is a hallmark of lichen sclerosus, manifested by purpura, erosions, and fissuring (Figures 14.9–14.12). Extragenital lesions show even more striking texture changes because of the dry nature of the skin. Sometimes, follicular plugging is visible in these lesions.

Figure 14.5 This cellophane paper crinkling of perianal skin is nearly pathognomonic for lichen sclerosus.

Figure 14.10 Fissures are common in women with lichen sclerosus, especially within natural skin folds.

Long-standing and severe disease is associated with resorption of vulvar architecture, with loss of the labia minora, and the clitoris is buried under the scarred clitoral hood (Figures 14.13 and 14.14). Sometimes, side-to-side anterior and/or posterior adhesions eventuate in narrowing of the introitus (Figure 14.15). Squamous cell carcinoma occurs in up to 5% of women with untreated lichen sclerosus (Figure 14.16)6. The primary risk factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma are elderly age of patients (probably an indication of longer duration of disease) and the presence of hyperkeratotic lesions (Figure 14.17)7.

Figure 14.14 Ongoing agglutination is clear on the anterior vulva of this woman with lichen sclerosus.

Figure 14.15 Anterior midline agglutination of the vulva has produced early narrowing of the introitus.

Lichen sclerosus is sometimes associated with patchy hyperpigmentation of the modified mucous membranes and vestibule (Figure 14.18). This pigment change ranges from mild, poorly demarcated, tan patches to wild, irregular, variegate brown and black patches indistinguishable from malignant melanoma. Pigmentary changes are nearly always benign, but biopsy and follow-up are prudent, since case reports of atypical nevi and melanoma in the setting of lichen sclerosus suggest that there may be an association8–10. Also, benign pigmented lesions in the setting of vulvar lichen sclerosus sometimes appear atypical histologically, confounding the differentiation of benign from malignant11.

Figure 14.18 Patchy hyperpigmentation is very common in lichen sclerosus, most visible after therapy.

Women with lichen sclerosus have an increased prevalence of hypothyroidism12, and many clinicians find that their lichen sclerosus patients appear to be more likely to exhibit concomitant vitiligo or lichen planus, although data are scant13,14.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Genital warts and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3 are sometimes white, but these are usually well-formed papules that are less symmetrical than lichen sclerosus. Cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris are erosive diseases that produce resorption of vulvar architecture that is indistinguishable from lichen sclerosus, but white color and texture change are usually absent or subtle.

Laboratory findings and histology

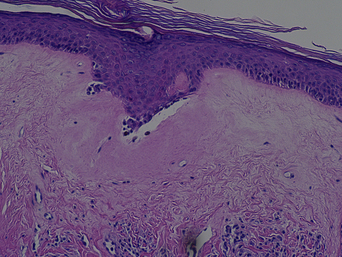

The classic histological changes of lichen sclerosus are most often found in areas of hypopigmentation and texture change. Lichen sclerosus of modified mucous membrane skin usually shows hyperkeratosis and thinning of the epidermis with loss of rete pegs. Early disease shows a lichenoid infiltrate of mononuclear cells at the dermal–epidermal junction with hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer. The diagnostic histologic hallmark of well-established lichen sclerosus is hyalinization of the upper dermis; a hazy, acellular substance reminiscent of gelatin (Figure 14.19).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree