3 Laser treatment of pigmented lesions and tattoos

Summary and Key Features

• Just as placement of tattoos has gained popularity, so has the number of people interested in their removal

• Black and blue tattoos are the easiest to fade with the most predictable results, whereas multicolored tattoos are the most difficult

• Of the various benign pigmented lesions that can be treated with laser, the easiest to treat are lentigines while the most difficult are the nevi of Ota, Ito, and Hori

• Pigment-specific lasers such as the quality-switched (QS) ruby (694 nm), QS alexandrite (755 nm), and QS Nd : YAG (532 nm and 1064 nm) continue to be the workhorse systems for both tattoo and pigmented lesion removal

• QS lasers remove tattoo pigment through photoacoustic injury, breaking up the ink particles and making them more available for macrophage phagocytosis and removal

• Fractional photothermolysis has provided expanded options for pigmented lesion removal in the last decade, though generally more treatment sessions are required and the cost is higher

• In general, patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I–III have a better response than those with skin phototypes IV–VI as the lasers used for pigment removal can also damage epidermal pigment

• Topical anesthesia is helpful when treating dermal pigmented lesions and tattoos

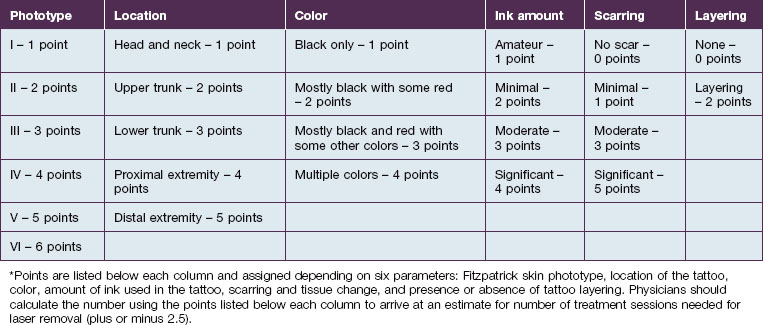

• Factors to consider prior to estimating the number of treatment sessions a patient will need for tattoo removal include: Fitzpatrick skin phototype, location, color, amount of ink used in the tattoo, scarring or tissue change, and ink layering

• As with any procedure, patient selection and preparation are important to success and photographs of the lesions should be taken prior to each treatment session

• Side effects of laser treatment for pigmented lesions include textural change, scarring, pruritus, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and immediate pigment change

• Tattoos with white or red ink carry an increased risk of paradoxical darkening after laser treatment, which is why test spots should be carried out prior to the first treatment session

• Caution should be exercised prior to treatment of a tattoo with an allergic reaction as the dispersed ink particles can elicit a systemic response

• For pigmented lesions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, pre- and postoperative treatment should include hydroquinone and topical retinoids

• Postoperative care includes gentle cleansing and a bland emollient while the skin heals

Pigment removal principles

QS lasers used for pigmented lesions include the QS ruby (694 nm), the QS alexandrite (755 nm) and the QS Nd : YAG (532 and 1064 nm) though it is also possible to use the long-pulsed ruby, alexandrite and diode lasers, or intense pulsed light (see Ch. 5). Within the last decade, fractional photothermolysis (‘FP’) has gained popularity for its ability to treat pigmented conditions such as melasma, solar lentigines, nevus of Ota, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (see Ch. 6).

Lesion selection

Just as important as patient selection is evaluation of the lesion itself. Tattoos can be divided into amateur, professional, cosmetic, medical, and traumatic categories. In amateur tattoos, a steel needle is used to deposit ink, which may be at various depths of the skin, whereas in professional tattoos, a hollow needle is used to inject ink into the dermal layer of skin. Amateur tattoos typically contain pigment of unknown sources such as ash, coal, or India ink (Fig. 3.1). On the other hand, professional tattoo artists often combine ink pigments to achieve novel colors and shading. Cosmetic tattoos using skin-colored tones are important to distinguish, as are medical tattoos such as those used as radiation markers. For traumatic tattoos, it is important to understand the nature of the injury that caused it so as to be aware of the type of material implanted in the skin prior to treatment.

Patient selection for tattoo removal

Though tattoos are increasingly popular, they often become a source of personal regret as up to 50% of adults older than 40 with tattoos seek their removal. It is critical that a thorough history of the tattoo be taken prior to deciding upon a treatment plan to establish appropriate patient expectations (Box 3.1). Kirby et al recently published a scale to help practitioners estimate the number of treatment sessions needed for tattoo removal to appropriately guide patients who often enter the laser removal process of their tattoos with uncertainty and misconceptions (Table 3.1). In the scale, numerical values are assigned to six parameters: (1) Fitzpatrick skin phototype, (2) location, (3) color, (4) amount of ink used in the tattoo, (5) scarring or tissue change, and (6) ink layering. The points for each parameter are combined, which results in the approximate number of treatment sessions needed to successfully remove the tattoo, plus or minus 2.5.

Box 3.1

Tattoo lesion patient history

Is it an amateur, professional, traumatic, cosmetic, or medical tattoo?

Is it an amateur, professional, traumatic, cosmetic, or medical tattoo?

What colors of inks / dyes were used?

What colors of inks / dyes were used?

Were inks mixed together to make the colors?

Were inks mixed together to make the colors?

Is there any white or skin-colored ink in the tattoo to the patient’s knowledge?

Is there any white or skin-colored ink in the tattoo to the patient’s knowledge?

Has the patient attempted to remove or alter the tattoo previously? If so, what technique was used?

Has the patient attempted to remove or alter the tattoo previously? If so, what technique was used?

Is the patient currently taking a retinoid?

Is the patient currently taking a retinoid?

Is there a history of herpes infection or cold sores in the proposed treatment area?

Is there a history of herpes infection or cold sores in the proposed treatment area?

Has the patient previously developed keloids or abnormal scars after prior surgery or injury?

Has the patient previously developed keloids or abnormal scars after prior surgery or injury?

Does the patient currently actively pursue a tan or use a tanning bed or bronzer?

Does the patient currently actively pursue a tan or use a tanning bed or bronzer?

Patient selection for benign pigmented lesion removal

As with tattoo removal, it is important to assess the patient presenting for benign lesion removal (Box 3.2). The greater the contrast between background skin and pigmented lesion, the more likely the laser surgeon is to achieve success. At preliminary evaluation, a Wood’s lamp examination may be helpful to assess depth of pigment. Understanding whether the lesion is epidermal, present at the dermoepidermal junction, or dermal will guide laser selection and also allow the physician to set realistic expectations for removal.

Box 3.2

Pigmented lesion patient history

How long has the lesion(s) been present?

How long has the lesion(s) been present?

Has a biopsy of the lesion been performed?

Has a biopsy of the lesion been performed?

Has it grown, bled without injury, or developed symptoms like itching or changed color?

Has it grown, bled without injury, or developed symptoms like itching or changed color?

Has the patient attempted to remove or alter the lesion previously? If so, how was this attempted?

Has the patient attempted to remove or alter the lesion previously? If so, how was this attempted?

Is the patient currently taking an oral retinoid?

Is the patient currently taking an oral retinoid?

Is there a personal history of herpes infection or cold sores in the proposed treatment area?

Is there a personal history of herpes infection or cold sores in the proposed treatment area?

Has the patient previously developed keloids or abnormal scars after prior surgery or injury?

Has the patient previously developed keloids or abnormal scars after prior surgery or injury?

Does the patient currently actively pursue a tan or use a tanning bed or bronzer?

Does the patient currently actively pursue a tan or use a tanning bed or bronzer?