CHAPTER 12 Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy

This chapter focuses on those acute and chronic infections that may have adverse consequences for the fetus or neonate, or warrant special attention and/or management during the course of pregnancy. The viral exanthems will be considered first, followed by notes on the dermatological manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The viral vulvar infections (herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV)) are considered next and leprosy is discussed in the concluding section.

Viral exanthems and pregnancy

Introduction

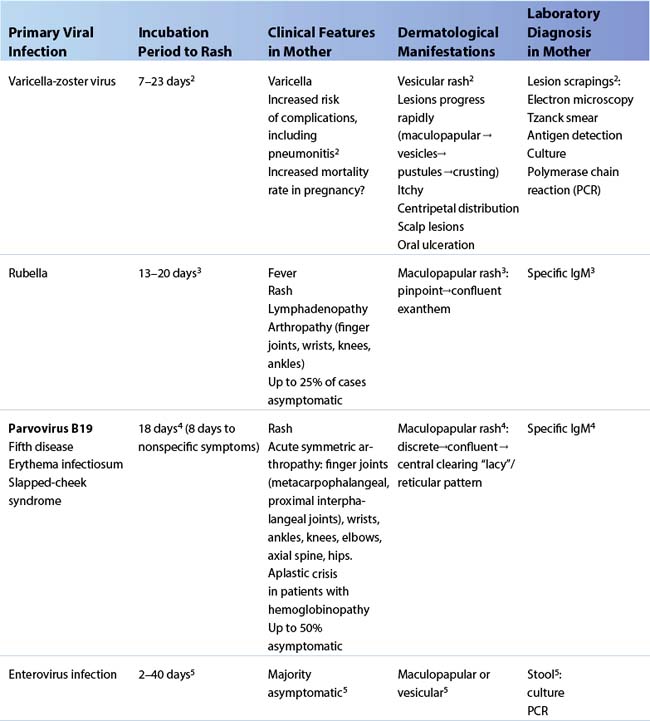

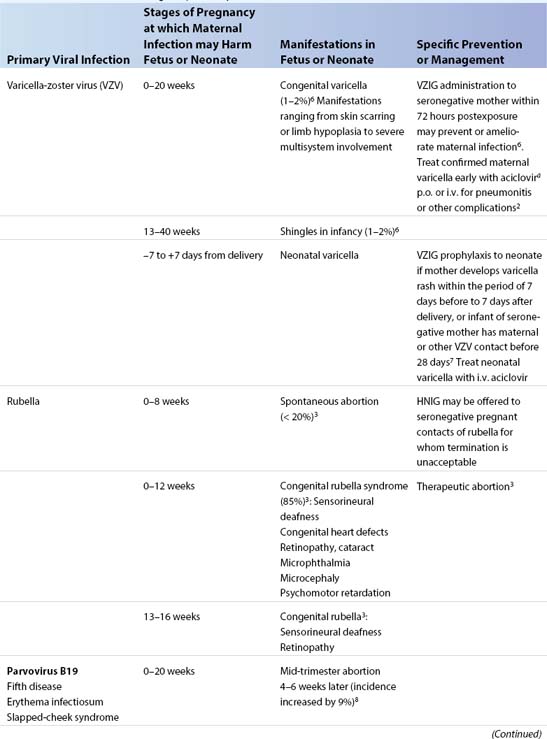

The viral exanthems, which cause mild disease in childhood, may be asymptomatic or give rise to severe disease in the expectant mother. Dermatologic manifestations generally take the form of a vesicular or maculopapular-type rash (Table 12.1). Primary maternal infection during pregnancy may have potentially serious consequences for the fetus or newborn (Table 12.2). The fetus may be infected in utero, giving rise to congenital infection, or acquire infection perinatally, with presentation in the neonatal period. The major risk period for exposure of the fetus or neonate depends on the viral etiology and the timing of maternal infection1. Table 12.2 summarizes measures to minimize maternal and fetal sequelae following exposure or infection. Practical points noted below supplement the tabular information.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV)

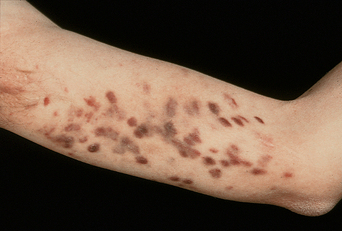

Primary infection with VZV causes chickenpox (varicella) (Figure 12.1) and induces VZV-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G, which persists for life2. Reactivation, typically occurring decades later, results in shingles (zoster). In temperate climes, where approximately 90% of adults are VZV-seropositive, varicella is uncommon during pregnancy and may be further reduced by VZV vaccination policies. In contrast, primary infection is delayed in subtropical and tropical climates, where about 50% of women may be susceptible2. Primary VZV infection may be severe in adults, and associated with greater morbidity and mortality during pregnancy1 (see Table 12.1). Although aciclovir is not licensed for use in pregnancy, it has been used extensively without adverse effects and should be considered in confirmed cases2 (see Table 12.2).

Figure 12.1 Varicella (chickenpox). Multiple, discrete, vesiculopustular, and maculopapular lesions on day 5 of rash.

In contrast to primary infection with VZV, there is no evidence that shingles/zoster in pregnancy presents any risk to the fetus or neonate6. The possibility of underlying HIV infection should, however, be considered in prospective mothers who suffer a recurrent attack, or cutaneous or visceral dissemination of shingles.

Maculopapular rashes

Rubella (Figure 12.2), parvovirus B19, and enterovirus infections may all present with red rashes, which in practice are clinically indistinguishable3,4,5. Neither a past history nor a current clinical diagnosis is reliable, and laboratory confirmation is required during pregnancy1. The arthropathy associated with both rubella and parvovirus B19 may persist for some weeks3,4. The possibility of HIV seroconversion should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of maculopapular rashes.

Rubella

Rubella (see Table 12.1) is currently a rare disease in women in many countries as a result of successful vaccination programs3. Congenital rubella syndrome (see Table 12.2) continues to be a problem in developing countries, however, partly as a result of unsatisfactory vaccination strategies11. Where therapeutic abortion is considered following rubella in the first trimester, the diagnosis should be confirmed by testing a second blood sample for specific IgM and/or a rise in specific IgG. Congenital rubella is diagnosed by the detection of rubella-specific IgM in cord or infant blood3.

Rubella reinfection has been described in seropositive individuals3. Reinfection in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy carries an 8% or lower risk of fetal infection, but fetal malformations are rare3.

Parvovirus B19

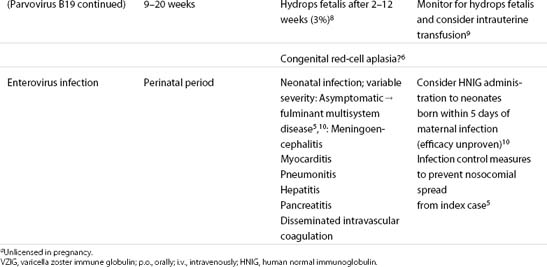

Primary parvovirus B19 infection is most common between 4 and 10 years of age. Whereas seropositivity is almost universal among adults in developing countries, about 40% of women in the developed world remain susceptible4. Parvovirus B19 infects red cells via the erythrocyte P antigen, classically causing a biphasic illness, the period of infectivity coinciding with the first phase of fever, mild anemia, and nonspecific symptoms4. In the second phase, coinciding with specific IgG and IgM production, rash and arthropathy are the main features (see Table 12.1). One or other phase, or both phases, may be subclinical. Joint involvement occurs in 80% of women with rash, and arthropathy may be the sole feature. The rash may wax and wane for some weeks after onset4. Primary infection during pregnancy is associated with an excess fetal loss of 9% and with nonimmune hydrops fetalis (fetal anemia in the absence of hemolysis) in 3% of fetuses 2–12 weeks following maternal illness8 (Figure 12.3). Intrauterine transfusion has been used to treat fetal hydrops9 (see Table 12.2).

Enteroviruses

Enteroviral infections occur frequently in healthy adults, usually without symptoms. Symptomatic infection may be associated with rubelliform or vesicular rashes5 (see Table 12.1). Some 1–2% of pregnant women may be excreting enteroviruses at term, with a high risk of transmission5. Neonatal infection presents at 3–7 days of age as an illness of wide-ranging severity. Coxsackie B viruses and echoviruses types 6, 7, and 11 have been associated with severe or fatal neonatal infection5,10 (see Table 12.2).

Human immunodeficiency virus

HIV infection is often associated with dermatologic manifestations, although less so since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).12 Many of these dermatoses occur commonly in the HIV-negative population but in HIV disease may present atypically and can be harder to treat. Other skin diseases are indicative of severe opportunistic infections. The majority are not usually altered by pregnancy. The ability to recognize them, however, is crucial as knowledge of a pregnant woman’s HIV status allows her to take up recognized interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV.13 Although antenatal HIV testing should be recommended to all pregnant women, uptake is variable, and the diagnosis may not be made until the woman presents with symptoms and/or a history of associated manifestations.

Folliculitis

Itchy, excoriated, follicular papules and pustules on the face, trunk, and upper arms are typical of eosinophilic folliculitis (Figure 12.4), which is almost diagnostic of advanced HIV infection. Treatment includes immune reconstitution with HAART, systemic antibiotics, antihistamines, antifungals, or phototherapy.14 Other causes of folliculitis include Staphylococcus aureus and Pityrosporum ovale.

Kaposi sarcoma

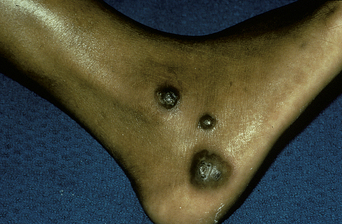

Kaposi sarcoma commonly affects homosexual men but can also affect women, particularly those from endemic areas. Human herpesvirus 8 is the causative agent. Lesions appear as patients become more immunosuppressed, but can occur early. Cutaneous lesions are usually purple-brown macules, nodules, or plaques (Figure 12.5). Oral lesions may be visible, often indicating visceral or pulmonary involvement. Histologic examination confirms the diagnosis and differentiates the condition from bacillary angiomatosis, which it may resemble. Treatment involves immune reconstitution with HAART, with radiotherapy, local or systemic chemotherapy when required.15

Varicella-zoster virus

HIV should be considered in patients with shingles. It may occur early in the course of HIV infection before the onset of other signs or symptoms. Multidermatomal involvement occurs, usually associated with significant immunosuppression. Atypical presentations include verrucous lesions (Figure 12.6) and indolent ulcers. Prolonged suppressive aciclovir treatment may be required for persistent or recurrent disease.15

Genital conditions

Genital warts may be associated with immunosuppression, and HIV should be considered in women with extensive recalcitrant genital warts and multifocal genital intraepithelial neoplasia. Similarly, frequent recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection may be a presenting symptom. Lesions may be extensive with advanced immunosuppression.15

Other conditions

Facial molluscum contagiosum is suggestive of advanced HIV infection. Seborrheic dermatitis, tinea, ichthyosis, and psoriasis are frequently seen in patients with HIV infection. Rarely, cutaneous cryptococcosis or histoplasmosis occurs. Drug eruptions are associated with some antiretroviral drugs.

Herpes simplex virus

Genital herpes can be caused by either HSV-2 or HSV-116,17. These closely related herpes viruses are characterized by lifelong persistence in the host following primary infection, the establishment of latency in neuronal ganglia, and intermittent reactivation. HSV-2 is predominantly sexually transmitted, first acquired in adolescence or early adulthood and associated with symptoms “below the waist.” In contrast, HSV-1 is classically acquired in childhood and is associated with disease “above the waist,” with primary infection manifest as gingivostomatis and clinical reactivation as “cold sores.” In practice there is considerable cross-over, with up to 50% of initial presentations of genital herpes attributable to HSV-118.

Genital herpes

Epidemiology

Serological testing, using assays that can discriminate between HSV-1 and HSV-2, has indicated that enumeration of clinical cases grossly underestimates the prevalence of genital herpes infection. Between 1988 and 1994, the seroprevalence of HSV-2 infection in persons aged 12 years or over in the United States was 21.9%, a 30% increase compared with the late 1970s19. Yet fewer than 10% of seropositive individuals reported a history of genital herpes infection19. Female sex, black race or Mexican-American ethnic background, older age, less education, poverty, cocaine use, and a greater lifetime number of sexual partners were independent predictors of infection. The prevalence of HSV-2 infection in the United Kingdom is considerably less, with values ranging from 3% (male blood donors) to 23% (sexually transmitted disease clinic patients)17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree