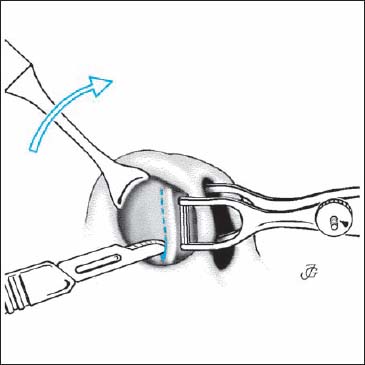

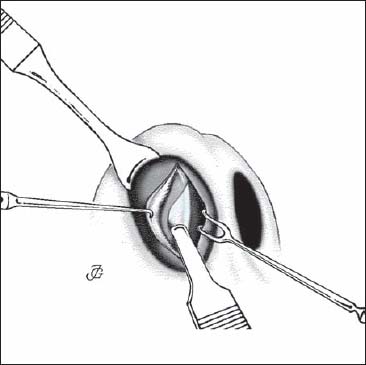

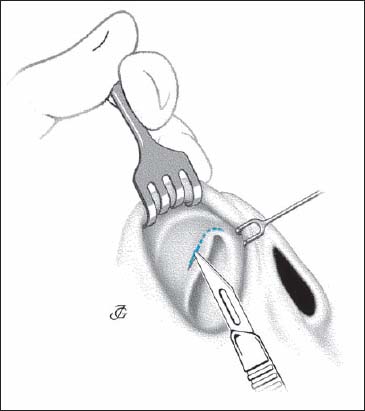

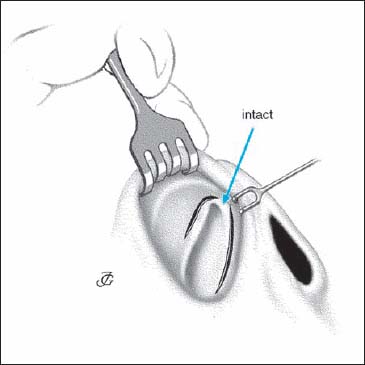

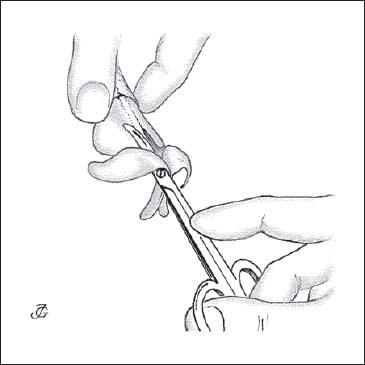

4 Incisions and Approaches There is often confusion about the terms “incision,” “approach,” and “technique.” From an anatomical or a linguistic point of view, the names of the following incisions are incorrect. Hemitransfixion: anatomically incorrect. This incision is not a half transfixion but an incision of the skin overlying the caudal end of the cartilaginous septum. We use “caudal septal incision.” Transfixion incision: linguistic misnomer. The word “transfixion” already implies that the tissues are cut through (Latin: transfigo, -fixi, -fixum = to stab). Hemitransfixion incision: anatomically as well as linguistically incorrect (see previous text). Marginal incision: causes confusion when used to denote the incision that follows the caudal border of the lobular cartilage (see Fig. 4.8). We use “infracartilaginous incision.” The term “rim incision” is reserved for an incision at the rim of the nostril (see Fig. 4.18). Glabellar incision: anatomically incorrect. This incision is not made at the glabella. It is made in a horizontal wrinkle at the depth of the frontonasal angle. Internal incisions are preferable to external incisions. External incisions are often said to become “almost invisible” when the tissues are handled delicately and sutured precisely. This may be true, but a completely invisible internal scar is always preferable to an almost invisible external one. Therefore, external incisions are avoided unless they are inevitable. For instance, the columellar inverted-V incision is inevitable in the external approach. When making an incision, we apply the following basic principles: Incisions are preferably made at places where a cartilaginous or bony underlayer is present. The cartilage or bone will prevent undesired retraction of connective tissue during the healing process. Therefore, very little soft-tissue retraction is seen at a caudal septal incision, where as unwanted scarring may result from a columellar incision, transfixion, vestibular incision, or intercartilaginous incision. Incisions are generally made at right angles to the skin or mucosa for optimal healing. It is advisable to slightly stretch soft tissues while making an incision. The belly of the blade is used, not its (pointed) tip. If a disposable blade has been used on rigid tissues, a fresh one should be used if further incisions are needed. Incisions should be as short as possible but long enough to provide sufficient access to the structures and allow the required maneuvers. If an incision is too conservative, the instruments will have to be forced in. This usually tears the edges, causing the wound to heal irregularly. This applies especially to incisions used for osteotomies, rasping, and inserting transplants. Incisions are only rarely continuous. All risk of postoperative stenosis must be avoided. There may be some exceptions, however. In surgery of the valve and the cartilaginous dorsum, the intercartilaginous incision may be connected with the caudal septal incision to obtain a sufficiently wide overview. Care must then be taken to restore normal anatomy when suturing. Suturing helps to adjust and fixate the tissues in their new position, avoid postoperative bleeding, and prevent scarring and stenoses (see Chapter 9, p. 331 and Fig. 9.38, 9.39 and 9.40). Stab incisions are usually closed by one suture or a small tape (e.g. Steristrip). The number of stitches applied depends not only on the length of the incision, but also on whether the incision was made solely to gain access or also to modify certain structures and their relationships. Changing the relationship between structures may require more sutures. The choice of suture material may be a matter of dispute. A thin monofilament artificial fiber, atraumatically mounted on a round needle, is probably the best. These stitches have to be removed after 3–5 days, however. When used in the vestibule, painless removal is usually difficult. We therefore use resorbable material for endonasal sutures. The caudal septal incision (CSI), also known as the hemitransfixion, is made about 2mm above and parallel to the caudal margin of the cartilaginous septum. It provides access to the septum, premaxilla and anterior nasal spine, nasal dorsum, columella, and floor of the nasal cavity. A right-handed surgeon makes the CSI on the right side, even if the caudal septal end is dislocated to the left. Since the surgeon is standing on the right side of the patient, a right-sided approach means that the instruments can be introduced and maneuvered from the right. Steps The CSI is closed by two or three 4–0 atraumatic sutures or by two or three 2–0 or 3–0 septocolumellar (SC) sutures. The caudal septal incision provides access to the following areas:1) septum; 2) premaxilla and anterior nasal spine; 3) nasal dorsum; 4) columella; and 5) floor of the nasal cavity. Septum: Depending on the pathology, the septum is approached by elevating the mucoperichondrium and the mucoperiosteum as discussed in Chapter 5 (p. 141 ff). Premaxilla and anterior nasal spine: The premaxilla and the anterior nasal spine may be exposed by the MP approach as illustrated in Figures 5.17 and 5.18. Nasal dorsum: The dorsum may be approached by undermining the skin as illustrated in Figure 4.5. Columella: Access to the columella, in particular the intercrural space, may be obtained by creating a columellar pocket as discussed in Chapter 7 (see Fig. 7.49). Floor of nasal cavity: The floor of the nasal cavity may be approached by elevating its mucoperiosteum using the MP approach (see Figs. 5.17, 5.18). Fig. 4.2 The caudal end of the septum is exposed by scraping aside the last perichondrial fibers with a Cottle knife or a pointed, slightly curved scissors. Fig. 4.3 IC incision used as an approach to the nasal dorsum and the lobule. The intercartilaginous (IC) incision is a cut made in the vestibular skin just cranial to the caudal margin of the triangular cartilage. The IC incision gives access to the cartilaginous and bony dorsum and allows retrograde undermining of the lobule. Steps Note The length of the IC incision depends on the kind of surgery to be performed. A (bilateral) incision of about 10mm is long enough to undermine the dorsal skin for repositioning the bony pyramid. A 10-mm incision also suffices for inserting crushed cartilage or a small cartilaginous transplant. If the transplant is large, the approach has to be made wider, while the skin has to be undermined over a broader area. For transplants in the supratip and tip area, a very small cut just above the valve angle may be sufficient. The IC incision is generally closed by two or three 4–0 atraumatic, slowly resorbable sutures. After valve surgery, more stitches may be required. If upward rotation of the tip is desired, suturing may be done in an oblique fashion by “advancing sutures.” This means pulling the tissues above the incision in a medial and cranial direction. The intercartilaginous incision provides access to: 1) the nasal dorsum and the cartilaginous and bony vault; 2) the valve; and 3) the lobule. Nasal dorsum and cartilaginous and bony vault: The dorsum (cartilaginous and bony vault) may be approached by undermining the dorsal skin according to the technique shown in Chapter 6 (p. 192 and p. 192, Figs. 6.2 and 6.44). Valve: The valve may be exposed as shown in Chapter 6 (p. 229 Figs. 6.65, 6.66). Lobule: Access to the lobular structures may be gained by retrograde undermining of the lobular skin as illustrated in Figure 7.3. Fig. 4.5 Access to the dorsum is gained by supraperichondrial undermining in cranial direction. The vestibular incision is a slightly curved cut made in the vestibular skin just lateral to the margin of the piriform aperture. It is used as an approach to the paranasal area, the piriform aperture, and the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. Steps

General

Terminology

Terminology

Incisions, Approaches, and Techniques

Misnomers

External vs Internal Incisions

External vs Internal Incisions

Basic Principles

Basic Principles

Main Incisions

Caudal Septal Incision (Hemitransfixion)

Caudal Septal Incision (Hemitransfixion)

Suturing

Access

Intercartilaginous Incision

Intercartilaginous Incision

Suturing

Access

Vestibular Incision

Vestibular Incision

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree