Trends in Surgeon Preferences on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructive Techniques

Keywords

• Anatomic • Anterior cruciate ligament • Reconstruction • Single-bundle • Double-bundle • Trends • Preferences • Perspectives

Key Points

Introduction

The long and often winding road to today’s anatomic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has been eventful and fascinating. The progress is demonstrated when looking back in the surgical history of the ACL, from the first reported repair of the torn ACL with silk sutures in 1895 by Sir Arthur Mayo-Robson of Leeds to today’s arthroscopic anatomic double-bundle ACL reconstruction.1 With increasing knowledge of ACL anatomy, the last decade has led to an evolution and a shift in paradigm in the surgical technique for ACL reconstruction. One of the new techniques, double-bundle ACL reconstruction, which aims to reconstruct both functional bundles of the native ACL, has been labeled as anatomic by several investigators.2,3 However, a reconstruction of both bundles can still be performed nonanatomically. This linguistic confusion has created the need for a definition and guidelines for what constitutes anatomic ACL reconstruction.4 An outline of the new surgical preferences is starting to form; orthopedic surgeons have shifted their preferences in arthroscopic technique, graft type, and fixation during the past decade.

Technical and surgical perspectives

Primary Repair and Augmentation

Several clinical attempts of primary repair of the ACL have been tried; but almost all of them report discouraging results, although short-term outcomes are positive.5,6 These results led orthopedic surgeons onto the path of different augmentation techniques that would theoretically not only promote healing but also prevent elongation and rupture. However, studies on augmentation together with repair revealed high rerupture rates and unfavorable outcomes.7 The incapacity of the ruptured ACL to heal and discouraging results of primary repair and different augmentation devices made orthopedic surgeons shift from performing ACL repair to reconstructions.

Open and Arthroscopic ACL Reconstruction

The arthroscopic evolution started in 1980 when David Dandy of Cambridge, United Kingdom, performed the first arthroscopic ACL reconstruction with an artificial ligament made out of carbon fibers.8 Thereafter, several researchers and orthopedic surgeons led the development and employment of the arthroscopic technique. The new technique was appealing because it was less traumatic than reconstruction with arthrotomy. Although it was a difficult procedure because there were no camera or monitors initially, studies revealed improvements in early symptoms.1,9–12 During the 1980s, the arthroscopic technique was primarily performed with a 2-incision technique whereby one incision was used for drilling the tibial bone tunnel and passing the graft and the other incision was used for drilling the femoral bone tunnel. This technique was also called the rear-entry technique because the second incision was localized posterior to the lateral femur condyle and drilling was performed using a guide, creating the bone tunnel from the outside of the femur condyle into the knee joint. The following decade, a new inside-out technique for femoral drilling was introduced. It was also called an endoscopic, one-incision, and transtibial technique. In this technique, an arthroscopic drill was introduced through the tibial bone tunnel and the femoral tunnel was created via this access. Several potential benefits were identified with this new technique. However, there was a concern that the new drilling technique would result in a nonoptimal femoral tunnel placement. Studies did not reveal any major significant differences between the 1- and 2-incision technique except for the study by Panni and colleagues.13–18 This study found a more vertical graft placement in the one-incision technique.18 Thus, the major advantage, transtibial drilling, is also the major limitation of the technique because it creates a restrictive link that prevents free movement of the arthroscopic drill and, therefore, limits the position of the femoral bone tunnel. By the end of the 1990s, most orthopedic surgeons used the transtibial technique, although criticisms of the new technique persisted.1 During this time period, 3 additional tools were commonly used: isometry, notch plasty, and the o’clock reference.

Isometry

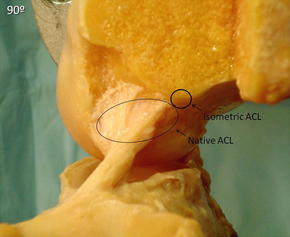

The concept of isometric graft placement was introduced during the 1960s.1 The term stems from the Greek word for equal measure. The procedure encompasses constant distance between the tunnels in the tibia and femur, or at least as little change as possible, during the knee’s range of motion.19 The reason for aiming at isometric graft placement was that research showed that a graft could be irreversibly stretched if elongated more than 4% and clinical studies revealed positive effects of isometric placement.20,21 With time and increasing understanding of the native ACL anatomy, researchers and orthopedic surgeons started to criticize the isometric concept. It was clear that the fanlike shape of the native ACL had an anisometric and nonuniform fiber anatomy. Furthermore, none of the bundles in the native ACL are isometric in their own entity.19,22,23 Also, the revealed isometric points were high and anterior in the femoral notch, far from the native footprint of the ACL (Fig. 1).20,24 It became obvious that the isometric concept was an elusive one, resulting in inferior knee joint kinematics compared with anatomic bone tunnel placement.24–26 The suboptimal knee joint kinematics were thought to be responsible for inferior clinical results and the development of osteoarthritis.27 This idea caused a marked decrease in the popularity and use of the isometric concept during the beginning of the twenty-first century.1 Today, focus is on respecting native anatomy and native tension patterns and not on isometry.4,26

Notch Plasty

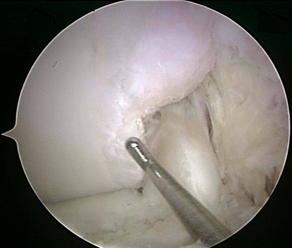

With the start of the arthroscopic ACL reconstruction, a surgical technique called notch plasty was used. This technique aimed to remove part of the inner wall of the lateral femoral notch to provide a better view of the posterior part of the notch and also to avoid graft impingement. However, notch plasty removes important osseous landmarks aiding in the femoral bone tunnel placement as well as a lateral graft displacement, which can change the kinematics of the graft.28,29 Furthermore, notch plasty can cause bone overgrowth with graft impingement (Fig. 2). With time, orthopedic surgeons started to use new arthroscopic techniques, such as the 3-portal technique or the 70° arthroscope, which aided in the visualization of the lateral wall of the femoral condyle, thus making notch plasty unnecessary for visualization purposes.30,31 Because the native ACL does not impinge, anatomically placed ACL grafts will not either. Hence, with increasingly anatomically placed grafts, a decrease should be seen in terms of the use of notch plasty for impingement purposes. Today, new surgical techniques have made the old indications for notch plasty obsolete; notch plasty is, therefore, limited to few and special cases.

O’clock Reference

The development and distribution of arthroscopic ACL reconstruction warranted a new technique for evaluating tunnel position. A reference system using the o’clock face had previously been developed for the assessment of femoral tunnel position on radiographs with the knee in extension, which was found to be reliable in this setting.32 Most likely because of its simplicity, it also became used for arthroscopic measurements. However, because it is a 2-dimensional reference, it does not take into account the depth and the o’clock position changes depending on the flexion angle of the knee joint.33 It became clear during the twenty-first century that the o’clock reference is not an adequate method of reporting tunnel position; hence, newer studies have started to use other methods of documenting femoral bone tunnels, such as intraoperative arthroscopic pictures.

Three-Portal Technique and Transportal Drilling

In the late 1990s and the beginning of the twenty-first century, several femoral drilling techniques were developed as the limitations of the transtibial technique were brought to light. During this period of time, it became clear that the nonanatomic transtibial ACL reconstruction did not result in satisfactory knee joint kinematics and seemingly did not prevent long-term osteoarthritis.1,25,34 Following the increased knowledge of native ACL anatomy and knee joint kinematics, new recommendations and surgical techniques were developed. The restrictive link created when drilling through the tibial tunnel, which could cause inaccurate and nonanatomic femoral tunnel position, was remedied by the development of the so-called transportal drilling.25,35–43 Initially, arthroscopic drilling was performed through the anteromedial portal; this was developed further to today’s 3-portal technique. The 3 portals consist of the lateral portal, central medial portal, and accessory medial portal (Fig. 3). These portals aid in both improved visualization of the lateral femoral condyle and in drilling of the femoral bone tunnel. In transportal drilling, the femoral tunnel is drilled independently of the tibial tunnel through the medial portal or the accessory medial portal. This technique facilitates anatomic placement of the graft, preservation of the ACL remnants, and isolated reconstruction of either ACL bundle.44 Several studies have provided data in support of the fact that native femoral footprints are reached more often through transportal drilling than transtibial.39–42 Interestingly, researchers have also started to promote the previous 2-incision technique once again. Similar to transportal drilling, there are no restrictions in femoral tunnel placement. However, there are 2 more advantages. There is no need for knee hyperflexion during femoral bone tunnel drilling, and it seems that longer femoral bone tunnels can be achieved.45 Whether these advantages are enough for orthopedic surgeons to start using this technique once again is yet to be seen. Today, transportal drilling has increased in popularity, whereas the transtibial technique has decreased.

Anatomic Single- and Double-Bundle ACL Reconstruction

The 2 functional bundles of the ACL named after their respective tibial insertion, the anteromedial (AM) and the posterolateral (PL) bundle, have been known since the Weber brothers’ thorough description of the ACL in 1836.1 The first reported double-bundle ACL reconstruction was performed in 1983 by William Mott in Wyoming. However, this reconstructive technique and the others that followed most likely did not replicate the native bundle tension patterns or footprints. In 1994, a review was published by Andersen and Amis46 that analyzed studies concerning tension on the natural and the reconstructed ACL. The investigators reported that different grafts required different tension and that graft placement and tensioning angle was important to restore normal stability.46 In 1997, Sakane and colleagues47 published on the in situ forces of the respective bundles. This article was the first of its kind and revealed that the in situ forces of the PL bundle were affected by knee flexion angle, in contrast to the AM bundle. It became clear later on that the AM bundle is taut throughout knee flexion and tightened to its maximum at 45° to 60° and that the PL bundle is tightened to its maximum when the knee is near full extension.26 Consequently, the PL bundle plays an important role when the knee is near extension and the same applies to the AM bundle when the knee is in flexion. Thus, one part of the ACL will always be taut during movement. These data created a shift in focus toward reconstructing 2 bundles instead of 1 bundle. At this time, double-bundle ACL reconstruction was called anatomic because it aimed to recreate functional bundle anatomy. However, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it became obvious that double-bundle ACL reconstruction was actually not necessarily anatomic.3 Most studies may have tried to replicate the tension patterns of the native ACL; however, the placement of the femoral tunnel was probably not always in the native femoral footprint. This idea became evident as the footprints were more thoroughly studied both in the clinical setting and in research in general. This newfound research also changed the bone tunnel placement for single-bundle ACL reconstruction to the native footprints of the ACL. Both biomechanical studies and a systematic review on randomized controlled trials found that double-bundle ACL reconstruction was more successful in restoring rotatory laxity.25,48 However, additional research was undertaken when it became evident that investigations performing double-bundle ACL reconstruction did not necessarily do it with respect to the native footprint.2,3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree