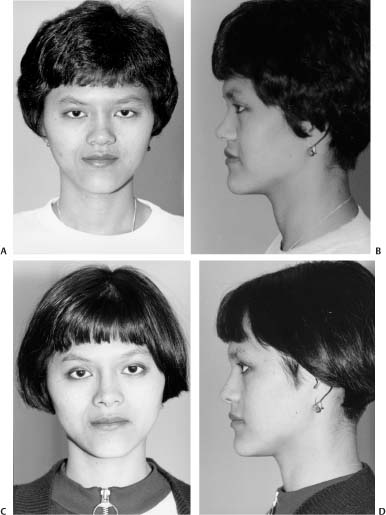

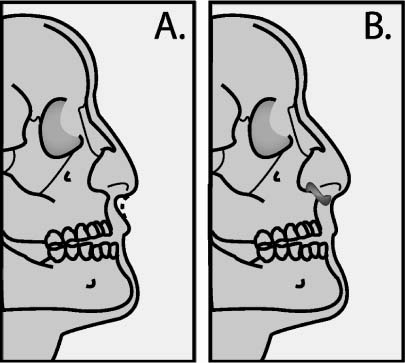

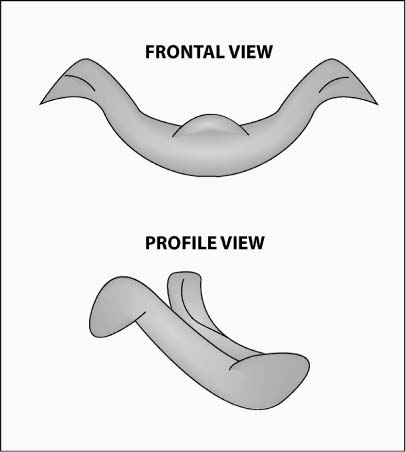

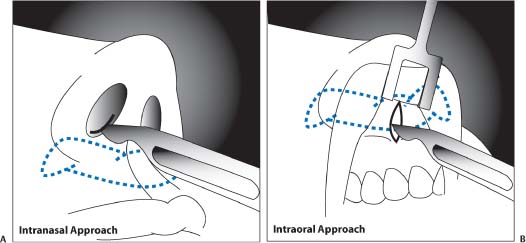

11 Although nasal implants are a mainstay of Asian rhinoplasty, facial implants elsewhere constitute a less customary desire for the Asian patient. A characteristic anatomic deficit that many Asians exhibit is maxillary and premaxillary hypoplasia. However, despite this skeletal deficiency, some Asian patients tend to be wary of augmentation in this region even if they concur that a higher malar eminence would be aesthetically pleasing. Their reservation stems partly from cultural unfamiliarity with this type of procedure, making it appear seemingly more ominous and even unnecessary. Interestingly, many Asian cultures actually do not desire a prominent malar eminence. Unlike Western cultures that prize a well-defined cheekbone as an attribute of feminine beauty, Asian societies often perceive a high malar prominence as a masculine trait, which combined with a square jawline makes the face appear overly boxy (refer to Chapter 12). Furthermore, augmentation mentoplasty is oftentimes perceived as a superfluous undertaking in overall facial harmony, despite digital imaging that may contravene this notion. However, mounting assimilation of second- and third-generation Asians in Western society has encroached on traditional perspectives in favor of adoption of Western ideals and customs. Therefore, the role of facial implants (e.g., malar and chin) will probably continue to rise in popularity among Asians reared in the West. Although malar and chin augmentations constitute familiar forms of implant surgery in the West, the unique Asian skeletal structure favors other types of alloplastic enhancement. Premaxillary retrusion is a common finding that is characterized by an acute nasolabial angle and contributes to a primate-like facies. These implants serve as effective adjuncts to rhinoplasty or equally well as an independent procedure. A relative zygomatic prominence in the Asian face creates a hollowed appearance in the temporal fossa that may be deemed unappealing. Temporal implants have received some interest in Asia but have also met with complications involving instability and mobility due to the activity of the overlying temporalis musculature. The posteriorly inclined forehead has also been construed as an unattractive feature in some Asian women, and silicone implants have been advocated to address this undesirable contour. However, similar to temporal implants, forehead implants may suffer from displacement secondary to the active frontalis muscle. As a general rule, implants that succeed particularly well are anchored to a fixed underlying bony structure (malar, nasal, chin) and are not subject to mobile forces. For instance, lip augmentation with solid alloplasts (a relatively uncommon request by Asians) has a higher likelihood for extrusion, infection, and mobility than more stable sites. In addition to the lip, the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds have been increasingly more popular areas for facial rejuvenation with alloplastic implants and may suffer fewer complications than lip augmentation. Implants can soften these unappealing folds, which may be relatively more accentuated in the Asian patient owing to a substantial buccal fat pad and less defined malar skeletal framework. Despite the benefit that solid implants may afford the central facial region, incisions (even very short ones) may remain quite visible for a long time after surgery in the Asian patient, making this option less than ideal. For this reason, the author prefers to use injectable implants in the smile lines and marionette lines in Asian patients when possible unless the patient is willing to accept the likelihood of visible incision lines that may endure for several months, if not longer. Currently, many options exist for soft-tissue or skeletal augmentation, of which solid implants constitute only one alternative. Liquid injectables may offer a viable solution for soft-tissue defects, but permanent injectable materials that cannot be easily removed following overinjection, infection, or late granuloma formation should be used with great caution. Various strategies for augmentation with injectable agents are reviewed in Chapter 13. This chapter focuses primarily on surgical methods of solid implantation. A versatile but potentially more invasive option for aesthetic augmentation is skeletal surgery that permits both reduction and augmentation and may also correct any orthognathic disharmonies. This type of surgery is covered in detail in Chapter 12, which is devoted to bony reduction and advancement procedures. Many materials abound for solid-implant augmentation. Traditionally, silicone has proven to be a well-tolerated alloplast that achieves its stability by fibrous capsule formation. Softer versions of this material that have been developed facilitate a lower extrusion rate in the nose. Many forms of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex, Advanta, Ultrasoft, etc.) have also entered the marketplace and have proven to be a reliable method for augmentation in the chin, cheek, nose, and elsewhere. The limited fibrous ingrowth of surrounding tissue enhances stability but still permits ease of removal. Polyamide mesh (Mersilene) may be a relatively inexpensive, well-tolerated, and stable implant for the chin and premaxillary regions but may be difficult to extract if this occasion should arise. Surgical preference and experience dictate implant selection, but all of the above implants have withstood the test of time and merit inclusion in the surgical armamentarium. As mentioned before, the main limiting factor for the Asian patient when considering solid implantation is the risk of obvious incision lines in the central portion of the face that remain conspicuous for an extended period of time. A detailed preoperative consultation, weighing the risks and benefits of each surgical procedure for the patient, will minimize postoperative dissatisfaction. Although premaxillary augmentation may appear to be a subject worthy of inclusion in a broader treatment of Asian rhinoplasty, this type of implant may not always be combined with rhinoplasty. Therefore, a separate section has been dedicated to this type of implant as an independent procedure, and the reader is encouraged to use this implant as deemed indicated. Although maxillary hypoplasia may not be considered an unfavorable trait in certain Asian cultures, premaxillary deficiency is more universally dismissed as an unpleasant feature. The premaxilla describes the midline bony segment that is bordered by the incisive foramina. Therefore, this osseous region lies immediately below the nose and constitutes the central upper lip. Premaxillary hypoplasia can impact on the surrounding structures, rendering the nasal tip relatively ptotic, the nasolabial angle acute, and the upper lip incompetent (Fig. 11-1A,B). The overall profile that results is reminiscent of a more simian appearance.1 Besides prevalence of this condition in certain pathologic diseases (e.g., cleft lip deformity and Binder’s syndrome), various ethnicities have a tendency toward premaxillary retrusion, namely, African, Hispanic, and Asian (Fig. 11-2A-D).2 Protuberant lips that also typify some of these ethnicities further compound the illusion of a retro-inclined nose-to-lip profile and may benefit from reductive surgery (see Chapter 13). If concomitant malocclusion exists due to deficiency of the premaxillary segment, orthognathic correction may be a more suitable surgical option than simple implantation (refer to Chapter 12 for greater detail regarding skeletal surgery). However, if premaxillary retrusion represents only an unaesthetic attribute and not a functional deficiency, then an implant may be the better solution. Various implants have been advocated that include autogenous (cartilage and bone) and alloplast material (Mersilene mesh and silicone). Although autogenous materials have proven a reliable method of augmentation in the Caucasian population, the greater severity of premaxillary retrusion often mandates a more substantial alloplastic material. Both intranasal and sublabial techniques have been promoted using various configurations of implants, ranging from small silicone blocks to larger flared profiles. The intranasal approach permits placement of smaller implants for less pronounced augmentation, whereas the sublabial approach facilitates better visualization, potential sectioning of the depressor septi muscle (which may otherwise add tension to the nasal tip), and placement of a larger implant. Both approaches have been applied with success to achieve the desired degree and breadth of augmentation. Figure 11-1 (A) Relative premaxillary hypoplasia may contribute to a simian-like appearance to the nasal and upper-lip profile: an acute nasolabial angle and ptotic nasal tip as well as a “gummy” smile and possibly incompetent upper lip. (B) A premaxillary implant placed either transnasally or transorally can enhance the nasal profile and upper-lip appearance. Figure 11-2 A 24-year-old Asian patient who underwent premaxillary augmentation and augmentation rhinoplasty and is shown 13 months after surgery. (From Fanous N, Yoskotovitch A. Premaxillary augmentation for central maxillary recession: an adjunct to rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 2002;10:415–422, Figure 5; with permission.) A bat-, or V-shaped, silicone implant (Implantech, Ventura, CA) (Fig. 11-3) that spans the entire nasal base may be inserted either transnasally or transorally (Fig. 11-4).3,4 The implant consists of a central component that modulates the degree of premaxillary projection and that is connected by two thinner arms to tapered winglike ends laterally. The implant measures ~38 to 40 mm in horizontal breadth, with the central component exhibiting a depth of 6 to 8 mm and a height of 6 to 7 mm, with 2 mm wide tapered arms that connect to 4 mm wide lateral, winged termini. The central component of the implant should not exceed the implant’s specifications of 6 to 7 mm, which would risk a visible ridge during smiling. The implant is thickest in dimension superiorly (under the columella) and tapers inferiorly over the upper lip to avoid this problem of a visible ridge formation. Finally, a shallow cleft resides on the posterior aspect of the implant’s midline to maintain the implant’s position over the nasal spine. The implant comes in two sizes, regular and large, with the former suitable for 90% of patients and the latter reserved for the remaining 10% of patients.* During the preoperative analysis, it is important to assess the nose-lip complex not only in repose but also during smiling. If the upper lip appears already long with poor dental show despite a retruded premaxilla, the surgeon is advised to augment the premaxilla cautiously, as the consequent lengthening of the upper lip may further limit dental show. Larger implants may also be palpable by the patient during smiling, and preoperative consent should include discussion of this possibility. In any case, conservative augmentation will avoid the potential for complications. Figure 11-3 The bat-shaped silicone implant is used to augment the deficient premaxilla. The implant is designed to enhance the retrusion of the entire nasal base. Figure 11-4 The silicone implant can be inserted via an intranasal (A) or transoral approach (B). Generally speaking, the intraoral route is less commonly used because it may predispose toward implant extrusion through the mucosal incision, as the implant is close to the mucosal surface. However, it can be reserved for implant removal if the surgeon should prefer this option. Although a premaxillary implant that extends across the entire nasal base may aesthetically benefit the patient, an implant that resides simply below the central, columellar component oftentimes may suffice (Fig. 11-5A,B). Clearly, use of autogenous materials is preferred whenever possible for the obvious reason of biocompatibility with a lower risk of infection and extrusion. Furthermore, the use of a morselized cartilage graft truly limits the chances of mobility and extrusion that could more likely occur with a larger implant style. However, use of this type of premaxillary type of plumping graft will fail to address a patient that requires significant premaxillary augmentation and the need for combined alar-base projection. Figure 11-5 This 39-year-old Vietnamese woman, who had undergone two rhinoplasties in the past and had her implant removed over a year before due to infection, presented with notable contraction of the nasal tip. She underwent revision rhinoplasty with a silicone implant and premaxillary augmentation with conchal cartilage grafting. Figure 11-6 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 1: The extent of the conchal bowl is identified postauricularly by driving a 25-gauge needle from the anterior to the posterior side of the ear and then marking this perimeter with a surgical marking pen. Figure 11-7 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 2: A no.15 Bard-Parker blade is used to incise the full thickness of the postauricular skin and a partial thickness of cartilage in a curvilinear fashion along the marked incision line. Figure 11-8 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 3: (A) The transected cartilage graft is carefully dissected free from the anterior auricular skin without damaging the overlying skin. (B) The graft is removed and then placed into saline until time to morselize and insert the cartilage into the premaxillary soft-tissue pocket. Figure 11-9 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 4: An auricular hematoma is prevented by a Telfa pressure dressing secured into place with a 2-0 silk mattress suture. At the end of the procedure, a conforming bandage should also be applied circumferentially around the head to exert extra pressure on the dissected ear. Figure 11-10 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 5: A no.15 blade is used to dissect a pocket down to the nasal spine along the caudal aspect of the columella and a short distance toward the nasal floor. As mentioned earlier, malar hypoplasia is a common attribute that typifies the Asian midface. Nasal augmentation surgery should always be tempered by the natural elevation of the malar eminence, as an overprojected dorsum looks particularly unnatural in the setting of a shallow midface. Despite the absence of a high malar bony prominence, traditional Asian immigrants are not troubled by this aesthetic deficiency and may express confusion over the possibility of malar augmentation. Curiously, some Asians request reduction of the malar region via skeletal surgery when the malar bone appears too high for their cultural sensibility (see Chapter 12). Nevertheless, increasing influence of Western ideals of beauty and a greater proportion of a third-generation Asian population in the West have contributed to wider acceptance of this type of surgery. Figure 11-11 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 6: Scissor dissection is taken down to the nasal spine until a recipient pocket is created for the premaxillary plumping graft. Figure 11-12 Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage, Step 7: After the pocket is prepared, the harvested conchal graft is morselized with a no.15 Bard-Parker blade into 1 mm pieces.

Implants in the Asian Face

♦ General and Anatomic Considerations

♦ Premaxillary Augmentation

♦ Premaxillary Silicone Implant

Design and Method of Nabil Fanous

Design

Surgical Technique: Intransal Route

Surgical Technique: Intraoral Route

♦ Premaxillary Augmentation with Conchal Cartilage

Surgical Technique

♦ Malar Augmentation

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree