CHAPTER 1 Hormonal Changes during Puberty, Pregnancy, and the Menopause

Introduction

This chapter summarizes the hormonal changes that occur during puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the menopause, and how these changes affect the skin physiologically.

Hypothalamic–pituitary axis

Situated above the pituitary gland, the hypothalamus initiates the release of the polypeptides that regulate ovarian function. The ovary cannot produce mature fertile oocytes (eggs) if the signals from the pituitary gland never start, cease prematurely, or are disordered. The female reproductive cycle is regulated precisely via biologic feedback mechanisms from the ovary, which alter the activity of the hypothalamus and pituitary. Normal physiologic changes in the functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis result in the hormonal changes that occur during the four main reproductive endocrine phases of a woman’s life: puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and the climacteric.

Puberty

Growth spurt

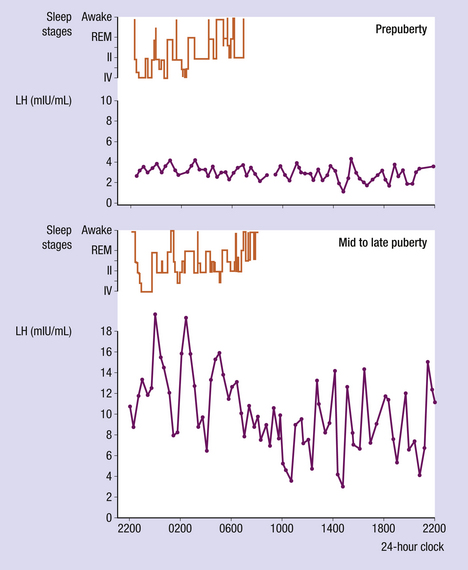

This large increase in height is mediated by an increase in growth hormone (GH) production by the pituitary gland. The greatest increase in the frequency and amplitude of GH takes place at night in a similar fashion to luteinizing hormone (LH) pulses (Figure 1.1).

Hormonal changes

During childhood, serum levels of the gonadotrophins – LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) – are low. During early to mid-puberty, however, there is a striking increase in the magnitude and frequency of LH pulses at night during sleep (see Figure 1.1). In late puberty, there is an increase in magnitude during the day, but not as marked as at night. Only when puberty is complete do the LH pulses lose their diurnal variation and settle into an adult pattern, with pulses approximately every 90 minutes during the follicular phase, and between 120 and 180 minutes in the luteal phase.

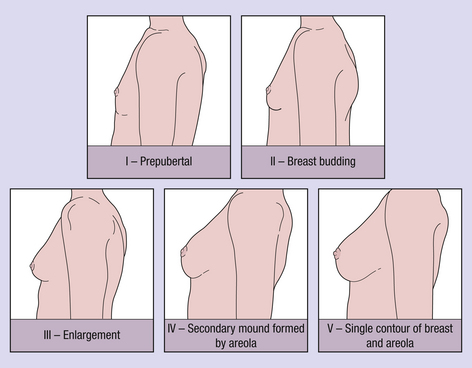

The increase in estradiol secretion stimulates breast development. The five stages of breast development take about 4 years to complete (Figure 1.2). Menarche (the first menstruation) usually occurs once breast development is quite well advanced – between stages III and IV1. Rapid breast development or increase in breast size, common during pregnancy and less common on the oral contraceptive pill, may cause stretch marks to develop, especially in the lateral margins of the breast, which may be of concern, particularly to younger women.

Several other changes also occur, which are important in understanding the physiologic changes in the skin. The first is adrenarche. This is an increase in the production of adrenal androgens, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate (DHEAS), which starts at about 8 years of age and continues until 13–15 years of age in both sexes. This increase is thought to stimulate the development of axillary and pubic hair, as hair growth and changes in sebum secretion are modulated predominantly by androgens in both sexes. Pubic and axillary hair growth usually starts before the breasts change following the increase in adrenal androgen levels, but reaches the mature stage at around the same time. The testosterone level increases in girls, as in boys, under the influence of LH, but most of it is converted into estradiol.

During puberty, the concentration of the main binding protein of the sex hormones (sex hormone-binding globulin, SHBG) declines in both sexes, despite the increase in estradiol concentrations in girls2. SHBG has a greater affinity for testosterone than for estradiol, with the result that, in most girls, more than 90% of circulating testosterone is bound to SHBG, thus limiting the effect that testosterone may have peripherally. The decrease in SHBG seems to be mediated by an increase in insulin concentration, which has been demonstrated in both sexes3.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

There is a group of girls who produce an excess of testosterone accompanied by morphologic changes in their ovaries, a phenomenon known as polycystic ovaries (PCO)4. Typically these girls never establish regular menstruation and have increased hair growth, usually of a male pattern, with an abdominal escutcheon, moustache, or other facial hair growth (Figure 1.3). They may also develop acne. Many girls with acne and/or hirsutism have polycystic ovary syndrome. These girls also have higher insulin concentrations and lower SHBG concentrations than their weight-matched contemporaries5.

Acne

Testosterone has major effects on the hair follicle and sebum secretion. Acne vulgaris6 (Figure 1.4) and hirsutism are never seen in prepubertal children with normal adrenal function, providing further evidence that puberty-related changes trigger these events. Although there is no evidence of increased androgen production in men with acne, most women with acne do have increased ovarian androgen production and a reduced SHBG concentration. Undoubtedly, genetic factors also play an important part in determining which girls will suffer and which will not. The pilosebaceous gland becomes more differentiated, increases in size, and changes its sebum composition. These changes are most marked on the scalp and around the nose, chin, and cheeks, as well as on the upper chest and back (see Chapter 2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree