CHAPTER 8 Hallux Rigidus

OVERVIEW OF SURGERY AND DECISION MAKING

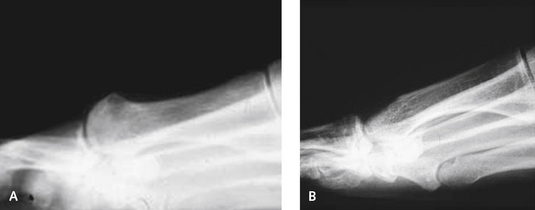

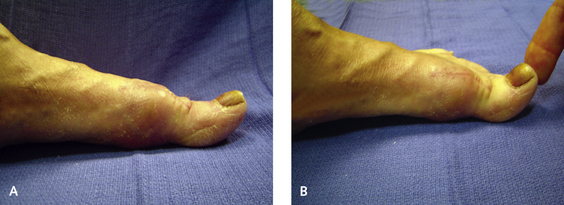

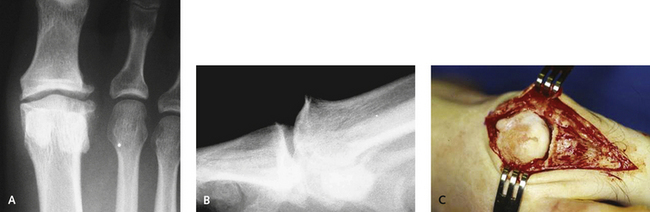

Occasionally, osteotomy of the first metatarsal is advantageous. Elevation of the first metatarsal may not have a significant role in the pathogenesis of hallux rigidus (Figure 8-1). Nevertheless, a most definite correlation exists between metatarsus elevatus and severe grades of hallux rigidus. In such cases, however, the elevation of the first metatarsal may be secondary to the severe contracture of the intrinsics and retraction of the volar plate, rather than a primary condition. Although osteotomy may be required for correction of primary or congenital metatarsus elevatus, one has to be careful with the notion that an osteotomy of the metatarsal is routinely necessary to alleviate dorsal impingement from hallux rigidus. Clearly, certain deformities will benefit from an osteotomy—for example, a long first metatarsal or one that is abnormally elevated. Other deformities require more care with decision making about the corrective procedure. Regardless of the extent of its deformity, an arthrodesis of the MP joint will not be successful in a patient with a fixed elevated first metatarsal and hyperextension of the hallux IP joint. The result will be only to create additional load on the IP joint, ultimately causing pain with further subluxation and extension. The hallux will have to be cocked up significantly to position the arthrodesis in order to unload it from the plantar weight-bearing surface. This cocked-up position in turn will cause rubbing of the tip of the hallux on the shoe. Note that in Figure 8-2, the patient had already undergone an unsuccessful cheilectomy. In the standing position, the hallux is rigidly on the ground and the IP joint is hyperextended. Further attempts at passive dorsiflexion of the joint only worsened the IP hyperextension.

CHEILECTOMY

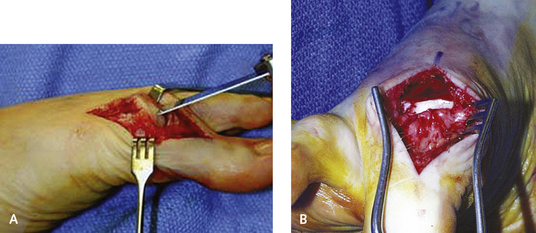

An incision is made dorsomedial to the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) tendon extending for 3 cm over the MP joint (Figure 8-3). The dorsal medial cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve must be avoided and retracted laterally. The capsule is incised, preserving a cuff of at least 5 mm medially for later closure. The capsule and periosteum are reflected off the metatarsal neck to expose the hypertrophic osteophytes dorsally. It can be difficult to expose the joint in the presence of large osteophytes, but the entire dorsal head must be exposed. Adequate exposure can be a problem in the foot with a large medial eminence as well as hallux rigidus, in which case the exostectomy will need to be performed with preservation of as much of the capsule medially as possible for closure. Alternatively, a medial incision with a medial capsulotomy can be used to approach cheilectomy in the presence of hallux valgus.

I prefer to use a chisel to remove the dorsal apical surface of the metatarsal head, because this gives me better control than that possible with an osteotome or a saw. The chisel is placed in the center of the metatarsal head, and one third of the dorsal surface of the metatarsal head is removed (Figure 8-4). At this point in the procedure, it always seems that too much of the metatarsal head is being removed, but the amount of bone that should be removed is almost always underestimated. When the head is viewed from above, one third of its volume seems like a large amount of bone to resect until an intraoperative radiograph is obtained, whereupon how little has actually been removed becomes evident. The ostectomy must be performed from distal to proximal, with removal of the dorsal osteophytes, and then the medial and lateral margins of the metatarsal head are contoured. If cysts are present in the metatarsal head, the ostectomy can be performed just dorsal to the erosion, or the head drilled with a Kirschner wire (K-wire), which may improve the fibrocartilaginous surface (Figure 8-5). Rounding off of the metatarsal head is performed using a rongeur and chisel, but care is taken not to dissect too far proximally. If the marginal osteophytes need to be removed, this can be done with the chisel, but again, it is essential not to go too far proximally on the lateral aspect of the head, which can result in avascular necrosis. The capsular attachment to the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head should be left intact. Range of dorsiflexion of the MP joint should be at least 65 degrees after the cheilectomy.

OSTEOTOMY OF THE PROXIMAL PHALANX (MOBERG OSTEOTOMY)

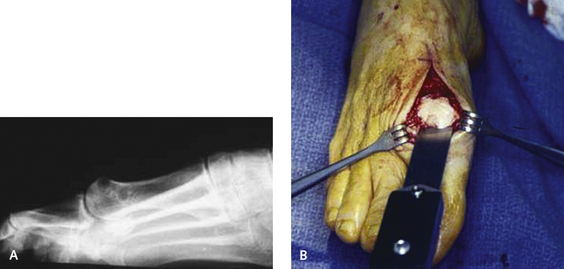

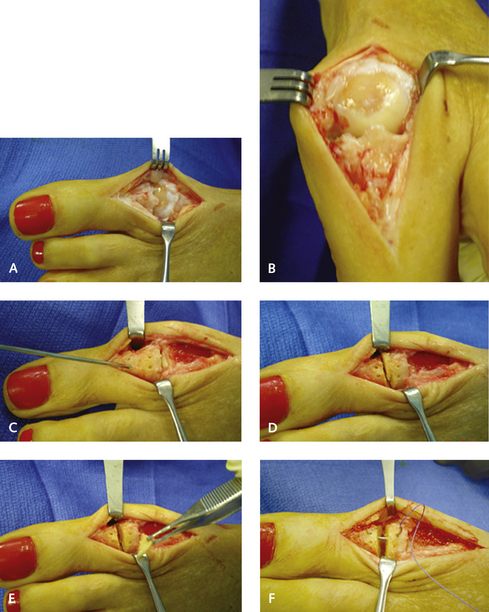

Osteotomy of the proximal phalanx—the Moberg osteotomy—is an easy operation to perform, with a predictable outcome. The hallux is dorsiflexed approximately 10 degrees off the floor. This operation does not increase range of motion of the hallux but simply facilitates clearance of the hallux so that at the starting point, the MTP joint is already in slightly greater dorsiflexion. I use this operation frequently, mostly for grade II arthritis. It is useful in cases in which additional “movement” is desirable, and, in particular, for patients who need an increased dorsiflexion of the hallux because of athletic and shoe wear needs (Figure 8-6). In patients with combined hallux rigidus and mild hallux valgus, a biplanar phalangeal osteotomy is performed to adduct and dorsiflex the hallux simultaneously, combining an Akin with a Moberg procedure. The surgery usually is performed in the setting of hallux rigidus, in conjunction with a cheilectomy, and the incision is simply extended more distally over the base of the proximal phalanx. The EHL must be retracted laterally and protected completely during the osteotomy.

The dorsal aspect of the cortex must be well exposed, and two sets of pilot holes are now inserted into the dorsal surface of the proximal phalanx. These are made obliquely at a 45-degree angle with respect to each other. The first set is made just distal to the articular surface and a second set approximately 1.5 cm more distally. These are unicortical pilot holes to be used for later suture fixation, and the osteotomy is planned in between these holes. A 1.5-mm slice of bone is removed with a saw. Once the bone wedge is removed, the base of the osteotomy is quite a bit more than 1.5 mm because of the width of the saw blade, and the osteotomy wedge must therefore be limited to prevent a cock-up deformity. A margin of 2.0 mm must be maintained on either side of the predrilled holes after the osteotomy, to prevent fracture through the hole and loss of fixation. The plantar cortex of the osteotomy is maintained intact, and a greenstick-type fracture of the osteotomy is created by first plantar flexing and then dorsiflexing the phalanx to completely close down the osteotomy. I open the osteotomy first using an osteotome, which loosens the plantar cortex but not the periosteal hinge. The osteotomy is secured with two sutures introduced through the predrilled holes using a curved tapered needle that fits the contour of the holes. These sutures will provide excellent stability, and screw, wire, or plate fixation is not necessary (Figure 8-7).