(1)

Department of Dermatology and Allergology Biederstein, Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM), Munich, Bavaria, Germany

(2)

Christine Kuehne Center for Allergy Research and Education (CK-CARE), Hochgebirgsklinik (High Altitude Hospital), Davos, Switzerland

1.1 Introduction

Allergic diseases are among the major health problems of our time. Especially the so-called atopic diseases, namely, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis (hay fever), and eczema (atopic dermatitis, atopic eczema), have increased in prevalence during the last decades dramatically (Alfvén et al. 2006; Borelli and Schnyder 1962; Rajka 1989; Schultz Larsen and Hanifin 1992; Williams 2000; Wüthrich 2001; UCB European Allergy Whitebook 1997). Atopic eczema as skin manifestation of the atopic trait represents today the most common chronic noncontagious inflammatory skin disease in childhood (Ring et al. 2006; Wüthrich 1975; Leungand Bieber 2003). Atopic dermatitis usually starts in childhood or early adolescence and is characterized by intense pruritus und disfiguring inflammatory skin lesions. The disease is associated with a dramatic impairment in quality of life. In times when economic reasons only consider mortality statistics measurable in dollars, we have to be the advocates of our patients suffering from chronic skin diseases. The skin as the surface and frontier organ of the human organism is characterized by a multitude of physical and chemical biological functions important for the integrity of human beings. Skin diseases lead to an impairment of self-confidence (Gieler 2006). When skin diseases start in childhood, they may influence the whole life history of a person in a long-lasting way.

At the beginning of this book, I want to start with some very personal reflections: since 1977 I have been engaged scientifically and clinically with this disease, when I performed a postdoctoral fellowship to do research with a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft at the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation in La Jolla, California, USA, in the Division of Allergy and Immunology under the guidance of Dr. Eng M. Tan. When I had told him that after this postdoctoral fellowship I most likely would join the Dermatology Department in Munich, he sent me to the library to decide in what field I would like to spend the 2 years.

I found that in those days many other and markedly rarer diseases attracted more attention than atopic dermatitis. So I decided to start here. Later my teacher in clinical dermatology, Prof. Otto Braun-Falco, tolerated this decision although he himself focused on psoriasis; he probably did not like atopic dermatitis so much, since the disease was too unprecise and “diffuse.” However, he always gave me the freedom to follow my scientific interests, and he accompanied the progress of my work very intensively and critically.

At the World Congress of Dermatology (Congressus Mundi Dermatologiae) 1977 in Mexico City, there was only one workshop to the subject “atopic dermatitis” among a program with over thousand lectures and posters, chaired by Professors Georg Rajka and Jon Hanifin with about 12 participants. Like me almost all of them have been attracted by this disease in the following decades; we have met often and became good friends. Many of them will be quoted in this book.

You cannot study atopic dermatitis without questioning the phenomenon of allergy. In the meantime, the disease—most likely due to the rapid increase in prevalence—has attracted much more followers also in clinical research. Even if 50 years ago the majority believed that allergy does not play an important role in this disease, but dry skin and psychology are the major factors, it became clear that this “atopic” disease cannot be studied without basic knowledge of allergy.

Thus, in the first edition of my allergy book “Angewandte Allergologie” (Allergy in Practice) 1982, I included a voluminous chapter on atopic eczema. In 1991 the first edition of the “Handbook of Atopic Eczema” (Ruzicka et al. 1991) appeared, in 2006 the second edition (Ring et al. 2006). In 1993 I was asked by the Ministry of Health of the Federal Republic of Germany to write an expertise regarding the “health care and prevention in children with atopic eczema,” which was finally published as a book in 1998 and gave the start signal to develop an educational program “Eczema School for Parents and Children” (Ring 1998; Gieler et al. 2001).

In 2002 the booklet for lay people “Eczema—Causes and Treatments” appeared, written together with Dr. Annette von Zumbusch (Ring and von Zumbusch 2002). Meanwhile other valuable books have been published (Bieber and Leung 2002; Williams 2000; Schneider et al. 2011).

Why do we need another book on atopic dermatitis?

The state of the art has shown a tremendous increase in knowledge in molecular genetics and experimental dermatology and allergology during the last years. New concepts allow the vision of new therapeutic strategies.

Beside this progress, there is the urgent need of many affected individuals and physicians dealing with this disease; it is not enough just to write a prescription! These patients are “exhausting,” and they need intense information about and introduction into causes and individual provocation factors. There is neither a “miracle” injection, “miracle” ointment, nor “miracle” pill which applied once will solve the problem forever.

On the other hand, there is no reason to become desperate; I fight against the so often used term “incurable” disease. It is true that there is a genetic predisposition with regard to barrier disturbance and hypersensitivity of the skin that gives rise to the formation of eczema, and which at the moment cannot be changed. However, the eczema itself can be treated very well and many patients are symptom-free over decades. They “grow out” of eczema.

Already today a considerable progress has been made in anti inflammatory basic dermatological and immunological therapies which unfortunately are not made available to all patients. To illustrate this in a very practical sense is one of the aims of this book.

1.2 History

1.2.1 First Descriptions

In most dermatology textbooks, historical reflections in the description of atopic eczema start with Robert Willan who in 1808 used the term “eczema” in a scientific morphological way (Schadewaldt 1980–1984; Wallach et al. 2004; Willan 1808). The term “eczema” was coined in the sixth century AD by the Greek physician Aetios from Amida who described the boiling and bubbling (eczeo = to bubble up) as it can be observed in a boiling soup (Aetios from Amida 1542). Aetios from Amida himself probably did not realize how illustratively he described the modern concept of pathophysiology of spongiosis in those times, namely, the intercellular formation of edema starting in the dermis and reaching the epidermis, flooding it with lymph until blister formation (more in Bergmann and Ring 2014).

Early descriptions can be found in the book of the Italian physician Girolamo Mercuriali (De morbis cutaneis) with a description of “lactumen” as crustose skin lesions on the scalp (Mercuriali 1601) which look like burned milk in a pan and were later called “cradle cap” or, in German, “Milchschorf.” Cradle cap is often regarded to be the first manifestation of atopic dermatitis in infants.

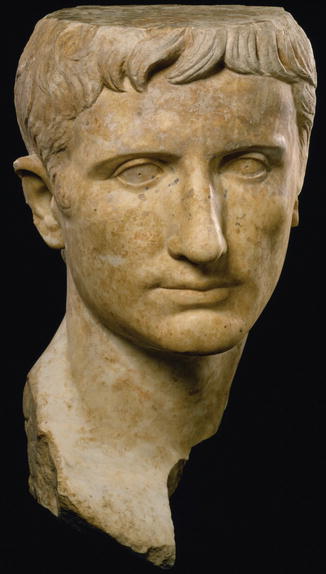

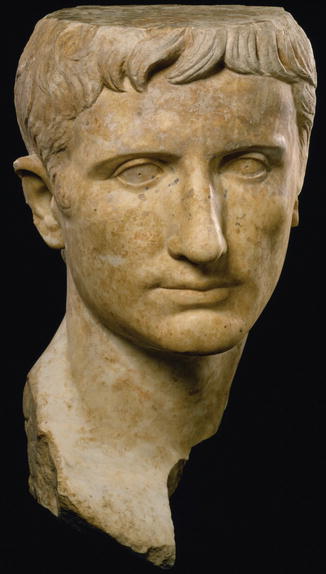

The first documented individual patient of history may have been emperor Octavianus Augustus (Fig. 1.1) from the Julian-Claudian emperor family (Mier 1975; Ring 1985) who, as we find in Suetonius “De Vita Caesarum (Suetonius 1958),” was suffering not only from “catarrhus” at the time of spring winds and episodic “tightness of the chest,” but also from “tormenting itch” with lichen-like skin changes (which he used to scratch on his back with a long instrument). Also in the Julian-Claudian emperor family, a positive family history (even according to today’s standards) can be found in emperor Claudius with perennial rhinoconjunctivitis and Britannicus as a horse-allergic individual (Ring 1985). The diagnosis “atopic eczema” for Octavianus Augustus seems plausible. Unfortunately, the many statues and images are of no help, since they always were idealized and did not represent individual portraits (Paul Zanker, personal communication 1983).

Fig. 1.1

Emperor Octavianus Augustus from the Julian-Claudian emperor family

The great rival of Robert Willan, the French Jean-Louis Alibert, described itchy and oozing skin changes in infants under the name “teigne muqueuse” where teigne, like “tinea,” just meant an inflammatory skin disease (Taïeb et al. 2002).

1.2.2 Milestones and Terminology

In Table 1.1 the most important milestones of history of atopic dermatitis are listed which also reflect the wide spectrum of names used for this disease.

Table 1.1

Atopic dermatitis/eczema: names in history

Eczema | Aetios from Amida |

Eczema | Willan |

Constitutional prurigo | Hebra |

Neurodermite diffuse | Brocq |

Prurigo diathésique | Besnier |

Early or late exudative eczematoid | Rost |

Atopic dermatitis/atopic eczema | Wise and Sulzberger |

Endogenous eczema | Korting |

Neurodermitis constitutionalis sive atopica | Schnyder and Borelli |

Atopic eczema dermatitis syndrome (AEDS) | Johansson et al. (EAACI task force) |

Eczema | Johansson et al. (WAO consensus JACI 2004) |

Erasmus Wilson described in detail an “infantile eczema,” and he also included skin changes without blisters as dry eczema. Ferdinand von Hebra, the great Viennese dermatologist, described a “constitutional prurigo” which we today would call a prurigo type of atopic eczema.

The great breakthrough came with the French School and was connected with the names Vidal, Jacquet, Brocq, and Besnier. Besnier coined the term “prurigo diathésique”(“dermatites multiformes prurigineuses chroniques exacerbantes et paroxystiques de prurigo de Hebra”) (Besnier 1892, 1901). For a long time, the disease also was called “Prurigo Besnier.”

Brocq and Jacquet coined the term “neurodermite” (Brocq 1903, 1927; Jacquet 1904), focusing on the dry lichenified skin lesions, and by enlarging the lichen simplex chronicus, Vidal gave a name for a similar, more generalized eruption. In Germany the pediatrician Czerny coined the term “diathesis” as a concept (Czerny 1905). Rost defined an “exudative state,” “früh- bzw. spät-exsudatives Ekzematoid” (“early or late exudative eczematoid”) (Rost 1929; Rost and Marchionini 1932). Soon in Germany, the term “neurodermitis” prevailed, while it was forgotten in France.

The discovery of transferability of allergy with serum by Prausnitz and Küstner (1921) and the observation of a familial tendency for atopic diseases with the definition of the term “atopy” by Coca and Cooke (1923) in the USA led to inclusion of allergic reactions in the description of this disease. In 1906 the Viennese pediatrician Clemens von Pirquet had created the term “allergy” (von Pirquet 1906). Today we see allergy as an environmental disease where, on the basis of a genetic predisposition, the organism reacts against environmental substances (Figs. 1.2 and 1.3). Allergy can be regarded as a specific alteration of immune reactivity towards a hypersensitivity disease (Ring 1982a).

Fig. 1.2

Allergy as environmental disease (According to H. Behrendt)

Fig. 1.3

Not every impairment of well-being through environmental factors is an allergy

Many dermatologists have problems in describing the morphology of this disease due to its wide spectrum and the difficulty to identify a classical primary lesion. Therefore, on national and international congresses, generally intense debates arose about this disease. In 1933 the American Marion Baldur Sulzberger—who had joined Joseph Jadassohn and Bloch in Switzerland—together with Wise defined the unifying concept of infantile and adult disease as atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema (Wise and Sulzberger 1933). For a long time this concept was neglected in Europe. Robert Degos in Paris liked the term “constitutional eczema” (Degos 1953). In the handbook chapter in the “Jadassohn-Ergänzungswerk,” edited by Alfred Marchionini, Urs Schnyder and Siegfried Borelli wrote on “Neurodermitis diffusa constitutionalis sive atopica” (Borelli and Schnyder 1962; Schnyder and Borelli 1962). Korting wrote his thesis on “endogenous” eczema where he focused on the abnormal reactivity patterns in the autonomic (“vegetative”) nervous system not only affecting the skin, but also provoking cardiovascular and even pupillary reactions with an increased cholinergic and decreased adrenergic reactivity (Korting 1954).

Hans-Jürgen Bandmann was an allergist and dermatologist and a supporter of the term “Neurodermitis” (Bandmann 1962). The transatlantic differences were overcome by the pioneers Georg Rajka in Oslo and Jon Hanifin in Portland/Oregon who, at an international symposium organized by Georg Rajka focusing on atopic dermatitis, developed a consensus on diagnostic criteria which are used until today (Hanifin and Rajka 1980). These symposia became the platform of researchers and clinicians all over the world interested in atopic dermatitis and a place for free discussions and exchange of information. It was there where the “Scoring System for Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD)” was born, allowing an objective determination of various severity grades of this chronic disease (Kunz et al. 1997; Stalder et al. 1993).

In 1983, Brunello Wüthrich—in analogy to respiratory atopy—proposed an “extrinsic” versus an “intrinsic” variant of this disease (IgE associated versus non-IgE associated) (Wüthrich 1983, 1989). Around the millennium, this conflict culminated in an intense nomenclature debate both in the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) (Johansson et al. 2001) and finally in a task force of the World Allergy Organization (WAO) (Johansson et al. 2004). Today the debate on terminology is not led quite so emotionally by many dermatologists, allergists, or patients. On the other hand, terminology is not a matter of sophisticated debate, rather pathophysiological concepts are hidden in names, and these concepts lead to quite different management approaches both in diagnostics and therapy.

Therefore it makes sense to understand what researchers, patients, or physicians mean when they talk about atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema.

1.2.3 Summary

The disease “atopic dermatitis” (atopic eczema) most likely is not new; the term “eczema” was coined around 600 AD. First descriptions of the disease can be found in the nineteenth century under various names, and only around 1900 the term “neurodermitis” was clearly differentiated from other types of eczema. In 1933, Wise and Sulzberger proposed the name “atopic dermatitis” or “atopic eczema.”

1.3 The Term “Atopy”

In a book on this disease, it cannot be avoided to briefly also touch the history of allergy and the term “atopy” (Table 1.2).

Pollen: skin and provocation tests | Blackley | 1873 |

Mast cell | Ehrlich | 1877 |

Neurodermite diffuse | Brocq | 1891 |

Prurigo diathésique | Besneir | 1892 |

Patch test for contact allergy | Joseph Jadassohn | 1895 |

Anaphylaxis | Richet and Portier | 1902 |

Allergy | von Pirquet | 1906 |

Histamine effects mimic anaphylaxis | Dale and Laidlaw | 1910 |

Immunotherapy (“prophylactic inoculation”) | Noon and Freeman | 1911 |

Transfer of hypersensitivity with serum | Prausnitz and Küstner | 1921 |

Atopy | Coca and Cooke | 1923 |

Reagins in atopy | Coca and Groove | 1925 |

Allergic diathesis | Kämmerer | 1928 |

Bronchial hyperreactivity | Tiffeneau | 1945 |

Shock fragment | Hansen | 1941 |

Cortisone | Hench and Kendall | 1949 |

Autonomic nervous dysregulation | Korting | 1954 |

Genetic basis | Schnyder | 1960 |

Types of pathogenic immune reactions | Coombs and Gell | 1963 |

Immunoglobulin E | Ishizaka K and T | 1966 |

Johansson | 1967 | |

House dust mite | Vorhoorst and Spieksma | 1967 |

Beta blockade in asthma | Szentivanyi | 1968 |

Fc-epsilon receptor | Metzger | 1977 |

Th1-Th2 concept | Mossman | 1987 |

Interleukin 4 | Coffman | 1988 |

Filaggrin mutation in eczema | McLean and Irvine | 2006 |

The term “atopy” has provoked a variety of interpretations during the 90 years following its birth. Atopic diseases, according to the classification of Coombs and Gell, range among type I (immediate-type) reactions (Fig. 1.4) (quoted in Bergmann and Ring 2014). In 1923, Coca and Cooke coined the term “atopy” to describe an “inherited” hypersensitivity against environmental allergens which manifests as asthma or “hay fever” (Coca and Cooke 1923). Different from other physicians who are not so critical, they knew their limits in philology and asked the Greek philologist Perry from Columbia University in New York to propose a term for this condition. Perry proposed “atopy,” meaning “not on the right place, out of order” (Ring 1983).

Fig. 1.4

Types of allergic reactions in the classification of Coombs and Cell (Modified by Ring)

Two years later, Coca and Grove proposed the term “atopic reagins” for the substances in serum with which the hypersensitivity of the immediate type can be transferred according to Prausnitz’ and Küstner’s experiments (Coca and Grove 1925). They added this characteristic to the term of atopy. Translated into today’s language this means that IgE antibodies are an important part of atopy.

In 1933, Wise and Sulzberger also included the skin manifestations in this spectrum and called it “atopic dermatitis” or “atopic eczema.”

In 1943, Coca modified his definition towards “atopy comprising a group of allergic diseases with a common hereditary influence and characterized by atopic reagins” (Coca 1943).

1.3.1 The Role of Immunoglobulin E

After the discovery of immunoglobulin E (IgE) as a carrier of the immediate-type hypersensitivity by the groups of Ishizaka (Ishizaka and Ishizaka 1967) and Johansson (Johansson 1967), atopy was identical with IgE-mediated disease for many authors (Juhlin et al. 1969; Ohman and Johansson 1974).

However, it soon became apparent that this was too simple. There are individuals with IgE-mediated diseases without family background like IgE-mediated penicillin anaphylaxis or insect venom anaphylaxis (Ring 2005).

In the 1980s, it was J. Pepys who stressed the concept that all human beings or all organisms under certain conditions can form IgE antibodies against protein allergens either after heavy exposure or when they have the “atopic background” (Pepys 1975) in abnormal concentrations.

1.3.2 Definition of Subpopulations

The normal relation between atopy and IgE antibodies can also be used to define subpopulations of allergic diseases, e.g., “atopic” asthma with IgE association versus “non-atopic” asthma without detection of IgE sensitization.

According to clinical experience, the disease itself does not differ as “asthma bronchiale” or “noninfectious rhinoconjunctivitis,” even if patients do not show IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. Therefore the term “intrinsic” or “non-IgE associated” became popular in respiratory atopy and was also used for atopic dermatitis by Wüthrich (1983).

1.3.3 Definition of EAACI and WAO

The new considerations of subpopulations “atopic” versus “non-atopic,” based on the detection of IgE antibodies, were not problematic in respiratory diseases; however, in the description of the skin condition, absurd terms like “non-atopic atopic eczema” appeared. While this was never a serious nomenclature in dermatology textbooks, in international debates these discussions took place, and the necessity was felt to come up with a new atopy definition. This was then started with a task force of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and later of the World Allergy Organization (WAO) with the following definition:

“Atopy is a personal or familial tendency, commonly starting in childhood and adolescence, to become sensitized and produce IgE antibodies after normal exposure against allergens, commonly proteins. In consequence, these persons develop typical symptoms like asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis or eczema” (Johansson et al. 2004).

According to this definition, all patients with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, or eczema without detectable IgE antibodies would not suffer from an “atopic” disease. In consequence, this terminology then would lead to an “atopic” versus a “non-atopic” “atopic dermatitis.” Therefore it became necessary to come up with a new name for the skin manifestations of atopy. The EAACI Nomenclature Task Force proposed “atopic eczema dermatitis syndrome AEDS” which aroused intense criticism and was not accepted, not the least for lack of logic since the adjective “atopic” again was used for the definition of the atopic disease and furthermore because of the association with the immunodeficiency syndrome AIDS.

Therefore the task force of the WAO found consensus by defining the term “eczema” anew in a way that dermatitis is the headline, and the term “eczema” defines the disease which before was called “atopic dermatitis” or “atopic eczema.” So the adjective “atopic” would only be used when IgE antibodies could be detected (Johansson et al. 2004, Table 1.1). In consequence, there would be an “atopic” versus a “non-atopic” eczema, similar to Wüthrich’s extrinsic versus intrinsic variant of atopic dermatitis.

The future will show whether these definitions will be adopted by practicing allergists and dermatologists (Bos 2002; Wüthrich 1999a).

The root of the problem in terminology can be found in the endeavor to define a clinical symptomatology and a pathophysiological mechanism with one term.

Early definitions started with the clinical symptomatology of disease and later included the detection of IgE antibodies.

The WAO definition starts from the laboratory determination of IgE and only later includes the typical clinical symptoms.

1.3.4 Our Definition of Atopy

Our definition from the Handbook of Atopic Eczema starts with the clinical symptomatology:

Atopy is a familial tendency to develop certain diseases (rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma bronchiale, eczema) on the basis of hypersensitivity of skin and mucous membranes against environmental agents, associated with increased IgE production and/or altered nonspecific reactivity (Ring 1991a). Today I would like to add “… plus epithelial barrier dysfunction.”

Therefore atopy is on the one hand a subgroup of IgE-mediated diseases, and on the other hand it is more (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

Atopy as subgroup of IgE-mediated allergic reactions

With this definition it is possible to describe intermediate states which can be found in the type of a “Gauss distribution” of atopic diseases which can be observed when comparing the two dimensions of “increased IgE production” with “altered nonspecific reactivity” (Fig. 1.6). Where both parameters overlap, there is no doubt of an atopic disease. Towards both sides of the curves, however, the situation becomes increasingly unprecise with entities such as “latent atopy” (only detection of positive skin tests or IgE antibodies in serum without clinical symptoms) or so-called “intrinsic” variants of atopic diseases (Ring 1982a, 2005).

Fig. 1.6

“Gauss” distribution of atopic reactivity

This dilemma only will be solved when the term “intrinsic” or “non-atopic” will not only be negatively defined by exclusion, but by a positive detection of a characteristic marker.

In my experience, the atopy definition from our textbook seems to be most useful for clinical practice.

1.3.5 Summary

The term “Atopy” has been coined in 1923 by Coca and Cooke and since then has changed its meaning several times. The problem is the lack of a clear-cut biomarker. If one uses immunoglobulin E as marker, there are clear-cut IgE-associated diseases which do not belong to “atopy” as, e.g., insect venom anaphylaxis. On the other hand, there are atopic diseases like asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, or eczema without IgE involvement. Therefore the definition given by the task force of the World Allergy Organization (WAO) which is based on the laboratory detection of IgE may be difficult in clinical practice. It excludes the clinically identical disease conditions where IgE association cannot be found (“intrinsic”). The author—together with others—believes that not only the tendency to IgE formation, but also nonspecific alterations of the epithelial barrier represent a basic feature of “atopy.”

1.4 Epidemiology of Atopic Eczema

There is no doubt that atopic eczema has increased in prevalence since the 1960s of the twentieth century dramatically in the general population (Kuehr 1999; Marsh et al. 1981; Ring 1991b; Ring et al. 2001a; Schäfer et al. 2003a, b, Schultz Larsen 1993; Schultz Larsen and Holm 1985; Schultz Larsen et al. 1986; Wahn and Wichmann 2000; Williams 2000). Significant differences exist in reported prevalence all over the world which only can be partly explained by methodological differences.

Some studies just describe an increase in incidence in the patients of a clinical department or office, others use population-based studies with questionnaires, and others require the diagnosis of a physician (dermatologist?). Other population-based studies with actual dermatologic examination have been performed (Schäfer et al. 1996). Most of these studies describe examinations in childhood; there are only few data regarding the prevalence of atopic eczema in adults (Worm et al. 2006; Möhrenschlager et al. in prep). Clinical examinations usually only represent a point prevalence, while questionnaires can detect cumulative prevalence rates over a lifetime.

According to general estimations, approx. 3 % of adults and 12 % of preschool children are affected, with consistently changing numbers between 1 and 25 % in the general population (Ring et al. 2012).

1.4.1 Prevalence of Atopic Eczema in Childhood

Atopic eczema is the most common noncontagious chronic inflammatory skin disease in childhood with a dramatic increase in prevalence in the last decades.

Early investigations from various countries in the years between 1939 and 1964 indicate a prevalence of 1.3–3.1 % in various populations (Ring 1991b; Wüthrich 2001). Studies between 1980 and 2005 show dramatically increased numbers ranging between 26 % for questionnaire-based and 32 % for actual investigations with dermatological inspections (Ring et al. 2012). The highest numbers were detected in the International Study of Allergy and Asthma in Childhood (ISAAC) (Asher et al. 2006; ISAAC 1998): in 90 centers, 256,410 children at the age of 6–7 years and 151 centers with 458,623 children at the age of 13–14 years were examined in 56 countries (Figs. 1.7 and 1.8). In these studies there was a worldwide variation with rather low figures in Albania and Iran and exceeding 20 % in the UK. Generally the prevalence of atopic eczema seems to be higher in Australia and Northern Europe compared to Asia and Eastern Europe.

Fig. 1.7

ISAAC study: prevalence of allergic rhinitis worldwide in 13–14-year-old children (ISAAC 1998)

Fig. 1.8

Symptom prevalence of allergic diseases including atopic eczema in the ISAAC study in 14-year-old children (ISAAC 1998)

Studies from Germany have been reported in the so-called KiGGS study (Kindergesundheits-Survey) (Schlaud et al. 2007) (Fig. 1.9). Contrary to hay fever and asthma (von Mutius et al. 1994a, b, 1998), atopic eczema showed a higher prevalence in Eastern Germany compared to West Germany (Table 1.3) (Schäfer 1996).

Fig. 1.9

Results of the KiGGS study (health survey of children and adolescents) of the Robert Koch Institute from the year 2003 to 2006 in 17,641 children and adolescents at 167 locations (representative sample). (a) Physician diagnosed atopic disease: atopic eczema, hay fever, allergic asthma. (b) Prevalence of sensitization against 20 common allergens (sIgE in serum), sensitization totally 41 %, aeroallergens 37 %, food allergens 20 % (According to Schlaud et al. (2007))

Table 1.3

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in East and West Germany (n = 1404 children) (Schäfer and Ring 2000)

Area in West Germany | Prevalence (%) | Area in East Germany | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Essen | 3.4 | Osterburg | 7.1 |

Duisburg North | 4.1 | Gardelegen | 8.4 |

Borken | 4.9 | Halle/Saale | 11.2 |

Duisburg South | 6.2 | Salzwedel | 11.7 |

Magdeburg | 13.8 |

Only few studies followed the prevalence rates over longer time periods with a consisting identical methodology: most of them show marked increases in prevalence (Fig. 1.10) (Schäfer et al. 1996). Most of these studies have been performed in Europe. Some of these studies now show a plateau formation or even slight decreases in prevalence in some European countries.

Fig. 1.10

Increasing prevalence of atopic eczema in various studies in the second half of the twentieth century (From Ring et al. (2006))

1.4.2 Causes for Increase

The causes for the increasing prevalence of this disease are still largely unknown. However, there are hypothetical concepts trying to give an explanation (Tables 1.4 and 1.5). The most popular is the “hygiene hypothesis” (Strachan 1989, 1997).

Table 1.4

Hypothetical concepts trying to explain the increase in allergy prevalence

Increased awareness and improved diagnostics |

Psychosocial influences |

Allergen exposure |

Lack of adequate stimulation of the immune system (“jungle” or “hygiene” hypothesis) |

Iatrogenic (medication) |

Environmental pollution |

Climate change |

Table 1.5

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in German children in the years 1990–2000 (Ring et al. 2012)

Atopic dermatitis (%) | |

|---|---|

5–8-year-old children | |

Mecklenburg Pomerania (1994) | 9.9 |

Brandenburg (1994) | 7.0 |

Saxony (1995/6) | 17.5 |

Saxony/Saxony-Anhalt (1990–1995) | 14.3 |

Saxony-Anhalt (1992–1993) | 10.0 |

North Rhine Westphalia (1985–1989) | 6.8 |

North Rhine Westphalia (Duisburg 1990–1995) | 9.2 |

North Rhine Westphalia (Münster 1994–1995) | 14.7 |

Bavaria (1988–1989) | 13.4 |

Bavaria Augsburg (1996) | 13.1 |

Bavaria Munich (1996) | 15.9 |

8–15-year-old children | |

Mecklenburg Pomerania (1994–1995) | 5.9 |

Berlin (1992–1993) | 10 |

Saxony (1995–1996) | 16.6 |

North Rhine Westphalia (Münster 1994–1995) | 10.6 |

North Rhine Westphalia (Bielefeld 1996–1997) | 7.2 |

Bavaria (1989) | 13.3 |

Bavaria (1995–1996) | 17.5 |

Apart from the genetic predisposition with an immunological and an epithelial basis, environmental factors play a role in modulating allergy development in an enhancing or protective manner (Behrendt et al. 1999; Wichmann et al. 1995). Allergen exposure may not be regarded as the only causal factor (Arshad 2003). A variety of additional substances or factors from the environment can modulate allergy development, in the sense of an enhancement like traffic exhaust with diesel particles, tobacco smoke, volatile organic compounds [VOCs], or in a protective way, like infections in early childhood, microbial contacts, and nutrition (Behrendt et al. 1999; Behrendt and Ring 2011; Cramer et al. 2007; Ege et al. 2008a, b) (Fig. 1.11). Climate change with an increasing tendency towards global warming may additionally contribute to a further increase in allergy prevalence (IPCC 2007, Behrendt and Ring 2011).

Defective training of the immune system by improved hygiene, less infection, and less parasite infestation (IgE antibodies in evolution provided the defense against large intruders) has been summarized under the term “jungle” or “hygiene” hypothesis (Behrendt et al. 1993; Björksten 1999; Herz et al. 2000; Krämer et al. 1999a; Ring and Behrendt 1993; Strachan 1989). Though these hypothetical concepts may be interesting for scientific investigations, they are no real basis for practical recommendations. General headlines like “dirt is allergy protective” or “natural infection is healthier than vaccination” have no scientific basis.

1.4.3 Own Investigations

At the Dermatology Department of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) in Munich, later at the Department of Dermatology and Allergy at the University Hospital Eppendorf in Hamburg, and then at the Department of Dermatology and Allergology at the Technische Universität, Munich, together with the Medical Institute for Environmental Hygiene (now Institut für Umweltmedizinische Forschung IUF) at the Heinrich-Heine-Universität in Düsseldorf, since 1988 we have studied over 40,000 children of the age of 5–6 years during the preschool medical examination; these investigations have been performed in various states of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bavaria, North Rhine Westphalia, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein) (Krämer et al. 2002; Schäfer et al. 1996; Überla et al. 1988). We found large differences between the different states in Germany, but especially between East and West Germany (Table 1.3), there was a clear-cut increase in the prevalence of hay fever with markedly increasing prevalence rates in East German children during 10 years from 1991 until 2000.

The rate of atopic eczema was high already, in some parts even significantly higher than in West German children in 1991 (Krämer et al. 2015).

1.4.4 Eczema Over Lifetime

One of the most common misconceptions when dealing with atopic dermatitis is the note that it starts “at birth.” This is what mothers often say to me; only when I precisely ask “was the baby born with eczema?,” she answers “of course not!” This is a crucial question since there are skin diseases occurring at birth or in the immediately following days which, however, almost never represent atopic dermatitis. This disease starts later, classically after 3 months, sometimes maybe already after 4–8 weeks. Since the differential diagnosis in neonates is difficult, the term “infantile eczema” (eczema infantum) is not bad. Apart from genodermatoses and infectious disease, it is mostly seborrheic dermatitis making problems in the differential diagnosis (see Sect. 2.4).

Probably 80 % of atopic dermatitis starts before the second year of life, yet there is an increasing number of patients showing or developing atopic dermatitis in adulthood.

With regard to the developing immune response over lifetime, the “miracle of tolerance” during pregnancy stands at the beginning, in the neonatal period Th2 predominates, and during childhood the immune system is stimulated and trained to become mature. In puberty hormonal influences play a role (see Sect. 3.6).

During adulthood, our immune system lives from memory. The first organ to really go into senescence is the thymus which already begins to turn into fatty tissue around the 17th year of life. During senescence, the immune system suffers a loss of regulation and a tendency to facilitate autoimmune phenomena.

1.4.5 Atopic Eczema in Adulthood

Several studies have been performed to determine the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in adulthood (Williams and Wüthrich 2000).

In 1980, Vickers published a prospective study on 2000 children from the pediatric dermatology department in Leeds with a follow-up of up to 21 years: in around 90 % of the children, eczema disappeared, and they stayed in remission when they had reached the age of ten (Vickers 1980). However, there were critical comments to this study, since it was only one observer who designed the study and examined the children, and also the definition of “remission” was not clear. Furthermore—and this is the most crucial critical issue—he also included “eczema infantum” which at first might have been seborrheic dermatitis (see above). Other studies showed a significantly worse prognosis with remission rates of only 10–70 % (Rystedt 1986). A retrospective study in Australia in 2600 outpatients comprised 519 patients with atopic eczema; 47 % had observed the new occurrence of atopic dermatitis at the age over 20 years (adult onset, 158 women, 85 men) (Bannister and Freeman 2000). The peak of the age group was between 40 and 50 years, but also over 70 years, and 10 % of newly occurring eczema were found.

The largest study was performed in Berlin as a cross-sectional study involving 13,300 subjects randomly selected at the age from birth to 99 years and in the years 1999 and 2000. This study used telephone interviews and—if there was evidence of skin lesions—a dermatologic investigation. From 1739 answered questionnaires, there was a cumulative 1-year prevalence of atopic dermatitis of 8.4 % and a point prevalence of actually existing skin lesions of 1.6 % (Worm et al. 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree