The history of rhinoplasty and surgery of the nose is as old as the history of medicine itself. The earliest known surgical writings, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, contain many references to the care of the traumatized nose. Dating from roughly 2500 BC, these texts from an Egyptian surgeon detail instructions regarding splinting, stenting, and bandaging a variety of nasal injuries. That these writings are copies of an even older source is readily apparent, and the original author may have been the great Egyptian physician Imhotep himself.1

Rhinoplasty appears again in antiquity in the writings of Sushruta, professor of medicine at the University of Benares during the 5th century BC. The Sushruta Ayurveda would eventually become part of the Sanskrit Veda, or holy books of the Hindu religion, and their content is astounding. Describing surgical techniques still in use today, Sushruta outlines the creation of pedicled forehead and cheek flaps for nasal reconstruction and even suggests the use of a leaf from which to create a template for flap planning.2 Because a common practice in ancient India was to mutilate the nose as punishment for a variety of offenses, these early nasal procedures were likely developed out of necessity.

It is unclear whether the Greeks had simultaneously developed similar techniques or owe their learning in this area to Indian influence.1,3 Regardless, these early rhinoplasty techniques survived through both the fall of Rome and the Arabic domination of India. By the 15th and 16th centuries, medical and surgical science was undergoing a renaissance along with the rest of western European culture, and Gasparo Tagliacozzi had refined the so-called Italian method of nasal reconstruction. The seal of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons still depicts his method of a staged transfer of skin from the upper arm for nasal reconstruction, although Tagliacozzi was labeled a heretic, and his body exhumed from consecrated ground.2

Interestingly enough, the modern era of rhinoplasty was ushered in by an article from a periodical, although not in the medical journal as we think of it today. An English surgeon, Colly Lyon Lucas, wrote a letter to Gentleman’s Magazine in 1794 detailing the use of a forehead flap for nasal reconstruction as seen by colleagues of his traveling in India.4 The Indian rhinoplasty was still being widely practiced by a brickmaker caste near Poona, and Dr. Lucas’s article sparked a renewed interest in nasal surgery that has never completely faded.

Since then, contributions have been made by a variety of surgeons, and the advent of antibiotics, aseptic technique, and controlled surgical anesthesia have all played an important role in creating the procedure that is commonly known today as rhinoplasty. Joseph Roe, an American otolaryngologist, generally is credited with completing the first intranasal approach to rhinoplasty in 1887. He is also thought to be the first to operate for purely cosmetic as opposed to reconstructive indications. A German orthopedic surgeon, Jacques Joseph, is considered the father of the modern rhinoplasty for his systematic study of nasal anatomic variants and the important work Nasenplastik und Sonstige Gesichtsplastik in 1928. Some have even commented that the field of rhinoplasty was “born full grown” thanks entirely to Roe’s extensive study.1 His pupils have brought us to the modern era of rhinoplasty, revision rhinoplasty, and ultimately the creation of this text.2

Patient Interview

Patient Interview

Revision rhinoplasty is arguably one of the most difficult to master of all surgical procedures practiced by the facial plastic surgeon. One must simultaneously play the part of investigator, anatomist, psychologist, and reconstructionist to achieve a successful result. Although this is true for any rhinoplasty, the task becomes more complicated in revision rhinoplasty. The revision surgeon must accurately assess whether the result was inevitable, whether the patient’s expectations were realistic, and ultimately what techniques may be used to address the patient’s concerns. The evaluation begins even before meeting the patient with a review of pictures predating the original surgery, if possible, and reports of the procedures performed. Although reports are valuable in giving the surgeon a general concept of what was done, it is only during the revision procedure that the fine details of anatomical modifications become clearer. At the same time, a thorough review of pertinent medical history, medications, tobacco use history, and other factors that may negatively influence a patient’s ability to recover from a surgical insult must be obtained.

During the patient interview, the surgeon should pay particular attention to developing a sound understanding of the patient’s concerns and motivations, including whether the patient’s goals are realistic. Although patient selection comes only with experience, if expectations appear unobtainable, the surgeon should exercise caution before proceeding.

The anatomic assessment should proceed as described in this and other texts. Facial analysis, facial proportions, and finally nasal function and structure should be assessed carefully with a sound physical examination and photographic analysis, paying careful attention to identify any of the classic complications of rhinoplasty. It is recommended that as much information be obtained and reviewed before the initial visit to allow adequate time to appreciate subtle anatomy and personality traits.5 Moreover, the surgeon should always remember that the goals of the surgeon and the patient are not always the same. Patients with specific complaints about obvious anatomical deformities or nasal obstruction may be easier to manage than those with more generalized dissatisfaction.

During the course of the patient interview, the surgeon must ride the fine line between performing nasal analysis and alerting patients to problems that they had never noticed before. When a decision is made to proceed with surgery, however, it is then crucial to fully educate patients about their anatomic variations, because patients frequently will identify these findings postoperatively and attribute them to the revision procedure. It is always beneficial to offer an explanation in advance rather than afterward when it might be perceived as an excuse.

Common Goals in Revision Rhinoplasty

Common Goals in Revision Rhinoplasty

Although each patient is clearly unique, patients seeking revision exhibit some readily identifiable patterns (Table 2–1). Through a careful analysis of these outcomes, the astute surgeon will learn to use techniques in primary rhinoplasty to avoid these complications. However, even in the best of surgical hands, complications do occur, and revision is sometimes necessary.6

Rhinoplasty techniques of the 1950s and 1960s commonly produced errors of overresection and alteration of the nasal structure that were standard practice at that time.7 It has become clear that many of the common findings today are a direct result of overresection, underresection, or improper reconstruction. Whether such results were inevitable or simply caused by poor aesthetic judgment and inexperience, the new goal remains the same: restore function while achieving a cosmetic result satisfying to the patient.

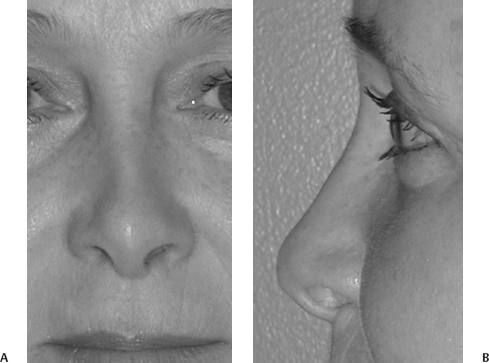

Overresection of cartilage leaves a weakened bony-cartilaginous framework to fight the contractile forces of the skin soft tissue envelope. Bossae may form where weakened lower lateral cartilages buckle under the force of wound healing and contraction (Fig. 2–1). They are more visible with thin skin, and asymmetry of the nasal tip becomes an important aesthetic finding. Correction of bossae formation focuses on resolving this asymmetry, either by reducing the bossae on the ipsilateral side or by augmenting the nasal tip on the contralateral side.8 Pinching of the nose may result from a similar overresection of lower lateral cartilage, causing nasal valve contracture and collapse with inspiration. Overresection of the dorsum can reduce the area of the internal valve by collapsing the upper lateral cartilage. Alar retraction may either be a real finding caused by overaggressive cephalic trimming or a perceived irregularity caused by a hanging columella (Fig. 2–2).

| Complication | Common Etiologies |

| Bossae | Skin contracting on overly weakened lower lateral cartilages, scar tissue formation |

| Pinching | Excessive resection of lower lateral crura |

| Nasal obstruction | Internal or external valve collapse from overresection of lower or upper lateral cartilages, septal deflection, osteotomies |

| Alar retraction | Scar contracture after excessive cephalic trim |

| Hanging columella | Inadequate shortening of caudal septum |

| Tip ptosis | Failure to reestablish tip support mechanism |

| Saddle-nose deformity | Overresection of nasal dorsum or septum |

| Overrotation | Excessive resection of lower lateral crura, lateral crural steal, others |

| Asymmetry | Septal twisting, poor osteotomies, scarring |

| Twisted nose | Inadequate septal repair |

| Inverted-V deformity | Separation of upper lateral cartilage from nasal bones |

Figure 2–1 Base view illustrates nasal tip asymmetry and pinching, bossae formation, and left alar notching after endonasal rhinoplasty in a patient with complaints of nasal obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree