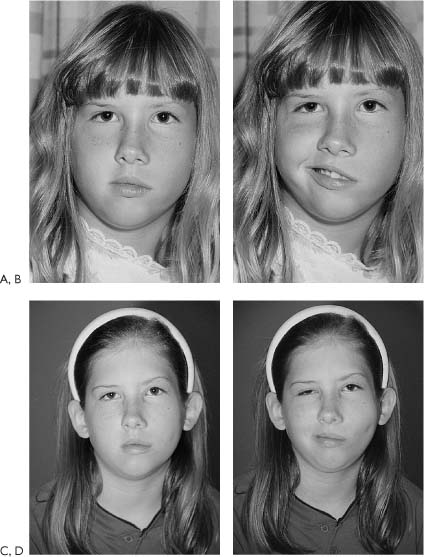

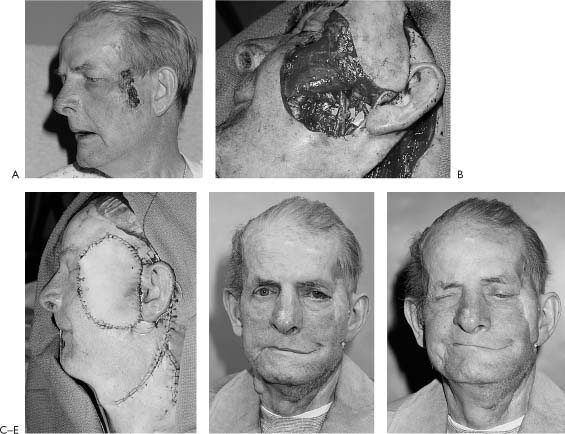

5 Since free muscle transfers were first used for restoring movement in patients with facial paralysis, the current state of the art for free tissue reconstruction has evolved to the concept of a single muscle providing a single function. The single function required most is elevation of the corner of the mouth to affect a smile. The issues to be addressed in this chapter include the historical development of innervated free muscle transfers, selection criteria of donor muscles and nerves based on case presentation, technical considerations in surgical planning, and an analysis of results as reported by current authoritiesters. Patients who desire mimetic dynamic reconstruction are candidates for this technique. The alternatives of static slings or regional muscle transfers, including temporalis and masseter, are described elsewhere (Chapters 4, 7, and 8). Compared with these more conventional techniques, free muscle transfers offer the possibility of a more natural and possibly subconscious smile. Free muscle transfer is indicated when the native facial muscles cannot be reinnervated due to paralysis of at least 2 years’ duration or resected for tumor. An ideal indication for this procedure is in the Möbius patient with complete or almost complete palsy where both the facial nerve and muscles are not available or in cases where the temporalis muscle is compromised, as would occur following skull base surgery. The preferred time to perform free muscle transplantation is when the child reaches age 5 years. By this time, anatomical structures have reached adequate size for surgical identification and manipulation. Furthermore, if a smile can be reconstructed for a child with facial paralysis, the social trauma can be reduced. This is especially critical when the child is entering first grade and meeting new children of various ages. In contrast, surgical rehabilitation should be delayed until the teen years for children with partial segmental facial palsy. The restoration of normal facial motion following facial nerve loss is beyond the capabilities of modern techniques; however, the replacement of a dynamic smile with symmetry at rest is an achievable goal. The idea that functional reinnervation would occur with the transfer of muscle tissue was reported first by Thompson.1 He grafted small segments of skeletal muscle onto wound beds with intact nerves, and demonstrated both engraftment and innervation. His work was not reproduced by subsequent authors, and the technique was abandoned. With the advent of modern microsurgical techniques, Harii et al.2 transferred the gracilis to the face with both neural and vascular anastomoses, demonstrating functional reinnervation. Harii defined the essential principles of free muscle transfer in his original work (Fig. 5-1). The technique was refined by Manktelow and Zuker3 who classified muscles by their morphology and identified fascicular territories within the gracilis that could be transferred independently. Terzis demonstrated that transferred or deinnervated muscles regain up to one-half of their power after reinnervation. She and her coworkers evaluated several donor sites for substitution of paralyzed facial muscles, and selected the pectoralis minor for its shape, size, and dual innervation.4,5 Subsequent authors have refined the technique and added additional donor sites. The selection of donor nerves for innervating a free tissue transfer begins with the assessment of the ipsilateral facial nerve. In many instances, tumor resection allows preservation of a tumor-free nerve segment in the fallopian canal, thereby permitting use of this original facial muscle inner-vator for powering the free muscle transfer. This situation occurs when a previous facial nerve graft has failed, rendering the target muscles no longer capable of reinnervation, or when wide resection of a tumor involving the facial muscles is required. Under these conditions, the facial nerve serves as the ideal motor donor site as it provides correct cerebral cortical orientation and substantial motor neurons to innervate the transferred muscle. The primary neural anastomosis provides early motor reinnervation of the transferred muscle without need for staged procedures. For reconstructions requiring external soft tissues as well as support for the corner of the mouth, a primary musculocutaneous reconstruction can be performed, which provides all of the elements of the needed reconstruction in one stage (Fig. 5-2). Figure 5-1. Kiyonori Harii, M.D., Professor and Chairman, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, University of Tokyo. Dr. Harii is credited with the first neurovascular free muscle transfer to reanimate a patient with facial paralysis. Professor Harii shares a brief historical note. The first neurovascular free muscle transfer was accomplished by Tamai and coworkers using dogs in 1970. Reading their paper soon after, I envisioned the procedure as providing a breakthough in treatment of long-standing facial paralysis in humans because we had found it difficult to obtain natural or near-natural smiles using the conventional procedures involving temporal or masseter muscle transfer. I achieved my first successful case in April 1973, in which the transferred muscle was innervated by a deep temporal nerve. One year later, good contraction beyond our expectations had been acquired, and the case was reported, together with another case, in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 1976. However, the acquired contraction was not completely satisfactory, as muscle innervation had not been procured by the facial nerve. The procedure, therefore, soon was modified to a two-stage method in which cross-face nerve grafting is combined. This has become most popular because innervation from the contralateral facial nerve produces an improved smile. When the ipsilateral facial nerve is not available for use, usually due to the treatment of an acoustic neuroma, alternative donor nerves must be recruited. The most common procedure today employs the two-stage procedure of a cross-facial nerve graft followed by a free muscle transfer as originally described by Harii et al.2 A sural nerve graft is anastomosed to contralateral facial nerve branches after intraoperative assessment of redundancy in the area of the zygomaticus branches. The rationale for this technique is that the contralateral facial nerve innervation will permit a mimetic smile, which can be accomplished subconsciously in a near-normal fashion and does not require cortical reorientation or conscious effort to activate the free muscle transfer. The principal drawback of this technique is that a two-stage procedure is required, as nerve regeneration must proceed across the long nerve graft prior to the transfer of the free muscle. While sacrifice of a portion of the uninjured facial nerve is required, this weakness usually improves the result, allowing the philtrum and nasal base to relax somewhat. The drawbacks of this procedure, however, are that an extended period of time is required between procedures, usually 1 year, and that the regenerated terminal branches of the facial nerve do not provide a large number of axons to the end of the nerve graft at the time of free muscle transfer. A second nerve repair is required, which further diminishes the number of available axons for the transferred muscle. In the final assessment, it is unclear whether the advantages of mimetic innervation outweigh the advantages of a single-stage operation with a greater number of motor axons available with other nerve donors. This author’s impression is that using the opposite facial nerve as a donor nerve is effective in children and young adults (under 30 years) in producing a mimetic smile (Fig. 5-3). For older patients, however, alternative donor nerves such as the hypoglossal are preferred due to the length of time required for reinnervation and the relatively weaker muscle power. The hypoglossal nerve has enjoyed widespread use for facial reanimation, particularly in cases when the facial musculature has been recently denervated and the facial nerve has been sacrificed, as in acoustic neuroma resections. The XII-VII hypoglossal nerve transfer provides facial symmetry at rest and some degree of voluntary smile.6 However, complications of this technique have included significant dyskinesias and hemiglossal paralysis, which lead to an unsatisfactory result in some patients. This technique is discussed in detail in Chapter 3. The hypoglossal nerve can be used to power a free muscle transfer effectively in a single-stage operation. By using a portion of the hypoglossal nerve, a high-density nerve regeneration can occur through the motor nerve of the transferred muscle, providing early motor recovery.7 These procedures are primarily indicated for bilateral, congenital facial paralysis where facial nerves are unavailable on both sides. Zuker’s experience in five patients with nine muscles resulted in eight muscles achieving an excursion of 4 to 10 mm with a good or very good results. One patient achieved a 1-mm excursion with a poor result. When only one third of the cross-section of a portion of the hypoglossal nerve is utilized, there is little deficit noted in tongue function (see Chapter 3). The donor site morbidity can be minimized further by using the distal most fibers that innervate the suprahyoid muscles.* This procedure is contraindicated in patients who have injuries to the hypoglossal, vagal, or glossopharyngeal nerves due to trauma, cancer extending to the cranial base, or congenital deficiency. Speech and swallowing function must be assessed carefully prior to sacrificing the hypoglossal nerve that might be critical for these functions. In appropriately selected patients, however, the bilateral partial hypoglossal nerve-free muscle transfers have proved to be exceptionally useful in the treatment of congenital facial paralysis while preserving tongue function (Fig. 5-4). The use of this nerve also affords the option for a one-stage facial reanimation with free muscle transfer and primary nerve anastomosis. The advantages of this procedure are that it avoids a two-stage operation with a 1 year period of time in between and provides high-density nerve reinnervation of the transferred muscle. In this author’s experience, the strength of motor reinnervation is considerably greater than with the cross-facial nerve graft. The drawbacks of this operation center around the need for re-education of speech patterns utilizing control of tongue motion to effect a smile. With a postoperative course of structured physical therapy, we believe that this one-stage operation can provide effective facial reanimation (Fig. 5-5). Figure 5-2. Use of innervated gracilis musculocutaneous free flap for reconstruction of radical cheek resection including facial nerve. A, Extensive squamous cell carcinoma invading parotid gland and facial nerve. B, C, Composite reconstruction. The gracilis muscle was used to suspend the corner of the mouth, reinnervated by the stump of the facial nerve. D, E, Postoperative result at 6 months showing static support of the corner of the mouth and satisfactory cosmesis. The patient died before reinnervation was effective. Figure 5-3. Facial reanimation using cross-face nerve graft. A, B, The operative views of a 7-year-old child with left congenital facial palsy. C, D, Postoperative views 2 years after gracilis muscle free flap and cross-face nerve graft were performed at the same setting. Zuker and Manktelow8

Free Muscle Transfers for Facial Paralysis

William M. Swartz, M.D.

Indications for Innervated Free Muscle Transfer

Historical Development

Selection of Motor Nerves

Ipsilateral Facial Nerve

Contralateral Facial Nerve

The Hypoglossal Nerve as Donor Nerve Tissue

Fifth Cranial Nerve

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree