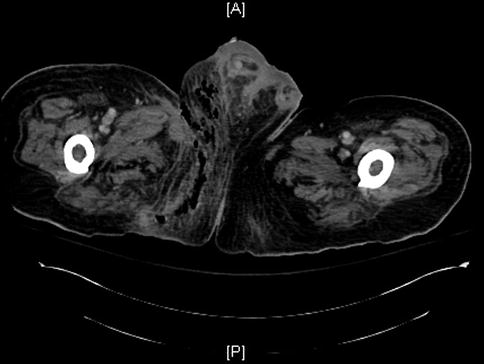

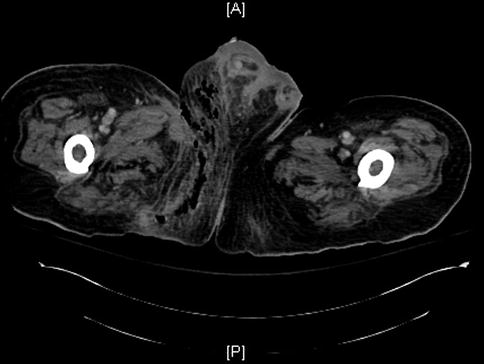

Fig. 32.1

Pathophysiology of Fournier gangrene

Originally, Meleney reported in his 1924 series of Chinese men with necrotizing infections that streptococcal species were the responsible genus for this virulence [5]. Since this report, most cases of Fournier gangrene have been found to be polymicrobial and when streptococcal species is isolated, it is cultured alongside 2–5 other bacteria. Staphylococcal species, enterobacteriaceae species, anaerobic organisms, and fungi are some of the more frequent causative organisms identified. In Fournier gangrene, it is believed that all of these organisms work in concert to create the final clinical picture. Macroscopically, necrotizing fasciitis produces rapid liquefactive necrosis of the subcutaneous fat and connective tissue, destroying skin perforators while sparing the overlying skin. This is in opposition to cellulitis and erysipelas, which affects the superficial layers of the skin and the lymphatics but spares the fat and fascia. With necrotizing fasciitis, liquefaction of fat leads to the development of a plane between the fascia and subcutaneous tissue that can easily be finger dissected. It also leads to massive edema and the pathognomonic “dishwater pus.” Veins traversing the inflamed fat thrombose and a vicious cycle of inflammation and necrosis propagates.

Researchers believe that a polymicrobial infection with a synergy of enzymes produces the macroscopic picture responsible for Fournier gangrene. For example, one organism may carry an enzyme that inflames vessels and leads to their thrombosis. Local tissue oxygen tension is decreased. This then allows an anaerobic bacterium to further propagate. This facultative anaerobe may have an enzyme such as collagenase in its arsenal that then digests fascial barriers and allows the infection to rapidly spread. Destructive proteases further destroy local tissue. A gram-negative bacteria then begins to propagate, releasing exotoxins and creating a cytokine storm and sepsis. Eventually, what started as a simple, indolent infection has become florid necrotizing fasciitis.

32.3 Diagnosis

A rapid diagnosis of Fournier gangrene reduces morbidity and mortality. However, the diagnosis is notoriously difficult and often missed until very late in the hospital course. Since there is no definitive test for Fournier gangrene, it is mandatory that the overall clinical picture be carefully considered. When there is doubt, early surgical treatment is preferred as the infection can progress to sepsis and death within hours. When unsure, a biopsy from normal looking adjacent tissue, a fascial biopsy, and a gram stain can be performed before beginning with a disfiguring debridement.

A careful history can also aid in the diagnosis. Patients who are diabetics, obese, or immunocompromised should be of special concern. A history of recent trauma to the anogenital region, followed by an indolent infection, can usually be elicited. Patients often report weakness, low-grade fevers, and chills for a prodromal period of 2–7 days.

The examiner needs to be especially cautious in those patients who are unable to communicate pain or hesitant to allow a full examination. One should not hesitate to do an exam under anesthesia if necessary. A massive pannus or mons pubis, with or without underlying phimosis, has had several severe necrotizing infections in our experience.

Nonspecific signs of Fournier gangrene include tenderness, swelling, erythema, and pain. Unfortunately, these signs mimic non-life-threatening infections such as cellulitis and erysipelas. In our experience and in the literature [3, 4], the most common distinguishing feature is severe pain and tenderness in the genitals. This pain is out of proportion to the exam findings. As the infection advances this pain progresses to paresthesias and numbness, indicating destruction of the cutaneous nerves. Similarly, with advanced infection the skin changes appearance from red, hot, and swollen with ill-defined borders to pale, mottled, blistered, and gangrenous with sharp lines of demarcation. Hemorrhagic bullae are a late finding, but suggestive of the disease. The odds ratio (OR) of bullae for necrotizing fasciitis compared to a cellulitis was found to be 3.5 with a 95 % confidence interval (CI) of 1.0–11.9 [6].

Subcutaneous emphysema is an often sought finding of necrotizing fasciitis and Fournier gangrene. However, the diagnosis must not be excluded if there is no crepitus on exam or air on radiograph. The majority of cases of Fournier gangrene we have treated have not had subcutaneous emphysema. This finding is only seen when gas-forming organisms are present.

The role that imaging such as x-ray, computed tomography (Fig. 32.2), and magnetic resonance imaging plays in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene is debatable. They should only be considered as an adjunct to the clinical exam in doubtful cases and should not be used to determine the extent of surgical debridement. In addition, performing these studies prolongs the time to treatment. If imaging studies are performed, it is important to reiterate that the clinical exam should supersede image finding. Gas seen on scans is usually an indication for operative intervention; however, in patients with chronic pressure sores, gas can be seen in the absence of Fournier gangrene.

Fig. 32.2

Chronic stage IV right ischial pressure sore that progressed to Fournier gangrene. The patient had radical debridement of his right scrotum, right orchiectomy, and lower right anterior abdominal wall

Ultrasonography has also been used in Fournier gangrene, mainly to assess blood flow to the testes. However, in our experience it is very difficult to perform this test, as the patients cannot tolerate the pain from direct pressure on the involved tissue.

If a frozen biopsy is needed to assist in the diagnosis, the pathognomonic findings of Fournier gangrene are (1) inflammation and necrosis of the fascia, (2) fibrinoid coagulation of the nutrient arterioles and veins, (3) polymorphonuclear cell infiltration, and (4) microorganisms within the deep tissue. The skin is often minimally involved in the disease process until very late.

32.4 Treatment

Fournier gangrene requires both emergent medical and surgical treatment. Patients with Fournier gangrene should receive immediate, empiric antibiotic therapy and emergent surgical debridement of the involved tissue. Aggressive measures should be taken to ensure normal end organ perfusion. It is critical that these three measures be taken before pursuing unnecessary diagnostic maneuvers:

1.

Resuscitation

2.

Parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics

3.

Surgical debridement

A multi-specialty approach is mandatory, with the involvement of surgeons, infectious disease experts, and intensivists. The hospital course is often prolonged and nosocomial complications are frequent. Urinary or rectal diversion may be necessary and, if so, should be done early.

The current antibiotic regimen of choice varies by region and hospital. The antibiotic spectrum should cover streptococcus, staphylococcus, the Enterobacteriaceae family, and anaerobes. Common first-line antibiotics for suspected polymicrobial Fournier gangrene are:

1.

Ampicilin-sulbactam or piperacillin-tazobactam plus clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin

2.

Imipenem/cilastatin or meropenem

3.

Cefotaxime plus metronidazole or clindamycin

It is essential that anaerobes be covered.

Clindamycin merits special mention in the antibiotic treatment of Fournier gangrene. It works by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, specifically decreasing the production of such proteins as SpeB [7]. Furthermore, its mechanism of action makes it not subject to the inoculum effect that occurs when large numbers of bacteria become slow growing and decrease expression of penicillin-binding proteins [7]. In animal models, clindamycin has been shown to be much more effective in the treatment of necrotizing streptococcal infections compared to penicillin and erythromycin, even when the treatment is delayed [8].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree