Chapter 43 Fibrous tumors of the skin

1. What are tumors of fibrous tissue?

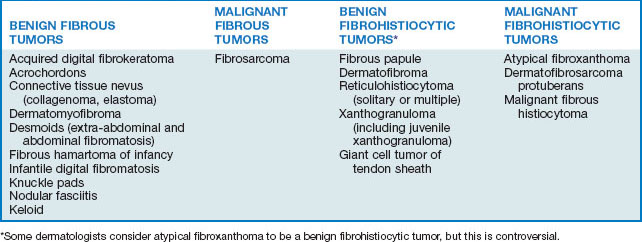

Tumors of fibrous tissue are mesenchymal tumors composed of fibroblasts or their variants. Fibroblasts produce normal structural components of the dermis, including collagen, elastin, and ground substance (dermal mucin). Most tumors of fibroblast origin produce collagen, but they may also produce dermal mucin or elastin as the primary product. Some tumors are composed primarily of myofibroblasts, specialized fibroblasts that demonstrate contractile properties because of cytoplasmic actin filaments. Other specialized fibroblasts may demonstrate phagocytosis, and tumors demonstrating this characteristic are referred to as fibrohistiocytic tumors. Tumors of fibrous tissue are conventionally divided into those that are fibrous and those that are fibrohistiocytic (Table 43-1).

2. What is an acrochordon?

An acrochordon (skin tag, fibroma durum) is a soft, flesh-colored to dark brown, often pedunculated, cutaneous papule usually located on the neck, axilla, or groin (Fig. 43-1A). It is probably the most common mesenchymal neoplasm. Acrochordons are often multiple, usually 1 to 4 mm in size, but occasionally 3 cm or larger in diameter. The larger baglike lesions often also contain some fat and are called soft fibromas or fibroepithelial polyps (Fig. 43-1B).

3. Is there a known cause for acrochordons?

An exact cause is not known. The frequent association of acrochordons with diabetes mellitus, obesity, pregnancy, menopause, acanthosis nigricans (see Fig. 43-1A), and certain endocrinopathies suggests that they are hormonally induced. However, the ubiquitous nature of these lesions in healthy older adults has been interpreted by some authorities as simply a manifestation of skin aging.

Demir S, Demir Y: Acrochordon and impaired carbohydrate metabolism, Acta Diabetol 39:57–59, 2002.

4. Are any complications associated with acrochordons?

Yes. The most common complications are recurrent trauma to individual lesions (e.g., laceration with a shaving razor) or spontaneous torsion and infarction of a pedunculated lesion. When a pedunculated lesion twists on its stalk, the blood supply is compromised and tissue ischemia occurs. Usually, sudden pain, swelling, necrosis, and even secondary infection result. Often, this sequence of events results in disappearance of the lesion.

5. Are acrochordons associated with intestinal polyposis?

Several widely reported studies asserted a statistically significant association between the presence of acrochordons and colonic polyps. However, other investigators, using methodology that better accounted for the fact that 60% to 70% of the elderly have acrochordons, demonstrated no statistical association. Most dermatologists believe that acrochordons are not a marker for colonic polyps but are simply more common in the elderly population, which is predisposed to colonic polyposis.

6. How can acrochordons be treated?

The simplest way to treat acrochordons is scissors-snip excision (usually without anesthesia). Smaller lesions can be rapidly treated by electrodesiccation or even cryotherapy (beware of postinflammatory dyspigmentation with cryotherapy). Larger lesions (>2 cm) can be shaved off after local anesthesia or excised.

7. What is a hypertrophic scar?

A hypertrophic scar represents excessive collagen deposition at a site of wound healing. Typically, the scars are initially red, raised, firm, and often pruritic. With time, they flatten and become white. Hypertrophic scars do not extend beyond the limits of the original trauma. Scars, including hypertrophic scars, are not usually considered to be neoplasms because they are reactive and eventually regress with time.

8. What is a keloid?

A keloid also represents excessive collagen deposition at a site of wound healing. Clinically, a keloid can be indistinguishable from a hypertrophic scar, though the excess collagen deposition of a keloid is usually more exaggerated. Microscopically, developed keloids can be differentiated from hypertrophic scars by the presence of large eosinophilic collagen fibers and more abundant mucin. Also, unlike hypertrophic scars, keloids uncommonly undergo involution, and they frequently proliferate well beyond the bounds of the original trauma. Some keloids, particularly on the sternum or upper back, even seem to develop without preceding trauma.

10. Do any factors predispose to hypertrophic scars and keloids?

Many factors can predispose individuals to develop hypertrophic scars and keloids:

• Certain drugs (e.g., isotretinoin) predispose to hypertrophic scarring, and most dermatologic surgeons defer any elective surgery for at least 1 year following discontinuation of isotretinoin.

• The type of injury and degree of tissue injury also play a role. Thermal burns, with their associated severe tissue damage, commonly produce hypertrophic scars or keloids.

• Regional variations exist. Skin that is continuously under tension or tightly stretched over bony protuberances and other anatomic peculiarities predispose to the development of hypertrophic scarring and keloids.

• Dark-skinned races are more prone to both hypertrophic scarring and keloid formation. Blacks are 2 to 19 times and Asians 3 to 5 times more likely than Caucasians to develop keloids. The tendency for multiple keloids to occur in families also suggests a genetic predisposition.

• Certain genodermatoses such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and progeria have all been reported to have increased risk for the development of keloids.

Table 43-2. Clinical Features That Distinguish Hypertrophic Scars from Keloids

| HYPERTROPHIC SCAR | KELOID |

|---|---|

| Any age group, especially children | Adolescents and young adults |

| All racial and ethnic groups | Blacks and Asians > Caucasians |

| No familial tendency | Familial tendency |

| Limited to sites of trauma | Sites of trauma or spontaneous |

| Onset within 2 months |