9

Facial Skeletal Implants

Michael S. Godin and Jason S. Hamilton

The ability to augment cosmetically deficient areas of the face is a powerful tool for the facial plastic surgeon to employ. The surgeon may spend hours improving the nose, for example, only to later find that the greatest cosmetic benefit he gave the patient at surgery was the chin implant, which took less than 30 minutes to place. Aging face surgery often turns back time, generally by resuspending fallen tissues in a more youthful position and removing the sagging excess. Facial skeletal implants can actually stop time by providing a permanent augmentation that will not change as the patient ages.

What follows is a description of the more common ways implants are used to augment the facial skeleton. For the purposes of this discussion, synthetic implants will be emphasized. The surgeon must always realize that biologic alternatives such as autologous (derived from the patient), homologous (derived from other humans or cadavers), and xenographic (derived from animals) implants are usually available and must be considered.1 Such materials include bone, cartilage, dermis, dermal fat, free autologous fat, and acellular dermis.

Prior to considering the variety of materials available for implantation into the human face, it is valuable to consider what the qualities of the ideal implant material would be (Table 9.1). When selecting a material for implantation, the surgeon is wise to consider how it measures up against such a list of characteristics, bearing in mind the context in which it is to be used.

The material should first and foremost be highly compatible with any type of tissue into which it is likely to be placed. These tissues are bone, muscle, fat, dermis, and occasionally the submucosa of the oral or nasal cavity epithelium. The material should be readily available and not prohibitively expensive. It should not be capable of transmitting disease, which is to say that if it is derived from an animal or human source, steps must have been taken to ensure that the material cannot harbor bacteria, viruses, or prion proteins. The implant material should be inherently resistant to infection. It must feel natural in the area it is placed. It is ideal if the implant will fix in place strongly enough to prevent migration but not so much that it cannot be removed if infection necessitating its removal occurs.2 The ideal material would be easy to shape and secure. Finally, the ideal implant material would have a long history of safety and longevity after implantation into human tissue.

|

♦ Choice of Materials

A great variety of synthetic materials have been used to augment the face with varying degrees of success, including paraffin wax, metals, ceramics, and plastic polymers.3 Though the focus of this chapter is on indications for and techniques of implant insertion, a description of the more commonly used synthetic implants follows.

Silastic (Polymethyl Silicone)

Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI), or solid silicone, is a high-viscosity, vulcanized form of dimethylsiloxane, which is the repeating unit in injectable medical grade silicone.4 Silastic is well tolerated by the body, which forms a fibrous capsule around the implant shortly after it is placed. While the Silastic is encased in the capsule, it is not bound to it in any way, and therefore displacement of the implant is possible. Persistent seromas have also been reported,4 and these in combination with the lack of firm fixation may lead to extrusion, especially after implantation into the nose or auricle.5 Despite these concerns, Silastic remains a popular choice for nasal augmentation, especially in Asian countries. It certainly may be easily shaped, and fenestrated implants that allow ingrowth of fibrous tissue for stabilization have been manufactured. Silastic is manufactured in varying degrees of firmness, known as durometers. A 10-durometer implant is often chosen for mandibular augmentation.3

Gore-Tex (Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene)

At the time of this writing, W.L. Gore (Flagstaff, AZ), the manufacturers of Gore-Tex, have announced the decision to discontinue the manufacture of Gore-Tex implants for facial cosmetic and reconstructive applications. According to company officials, this decision reflected no problems with clinical use of the material or, for that matter, with its popularity. The company will continue to manufacture expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (e-PTFE) for medical use and has shifted its entire focus to cardiac and vascular surgery applications. This comes as a bit of bad news for surgeons, the authors of this chapter included, who have come to rely on e-PTFE as a facial skeletal implant because of its excellent durability, natural feel, supreme ease of contouring, and biocompatibility. Gore-Tex is microporous, with an average internodal space of 30 μm, which allows sufficient ingrowth of tissue to prevent migration while preventing more robust tissue incorporation, as would occur with a porous implant or mesh material. Therefore, if there is a problem necessitating removal, it can be removed without undue trauma to surrounding tissues. Gore-Tex does well on bone and when contacting fat or muscle. It should not be placed in contact with dermis as an inflammatory reaction frequently occurs. Gore-Tex has been used successfully in nasal augmentation with follow-up of more than 10 years reported.6 It also has an enviable record of reliability in chin augmentation. A 2003 report of pooled data by six facial plastic surgeons revealed a complication rate of less than 1% in 324 patients.7 Gore-Tex has been an excellent implant material that is close to the ideal in many ways. It is hoped that a similar type of implant will become widely available to take its place.

Medpor (Porous High-Density Polyethylene)

Medpor (porous high-density polyethylene [HDPE]; Porex Surgical, Newnan, GA) is a firm skeletal implant material with pore size in the 100-μm range and a pore volume in the range of 50%, as measured by mercury intrusion porosimetry.8 Medpor can be carved with a standard surgical blade, and thin sheets of it may be sutured together to add thickness where desired. It is available in blocks and sheets. The material’s shape can be molded by submersing it in hot sterile saline (above 180°F per the manufacturer) for several minutes then bending it to the desired shape and allowing it to cool. The use of a cold sterile saline bath can accelerate the cooling process.8 Romo et al reported good results using HDPE in 187 rhinoplasty patients. Both primary and revision cases were included, and follow-up ranged up to 3.5 years. Five (2.6%) of the implants required removal due to infection or breakdown of overlying skin.9

Of the implants described, HDPE is the only one that can truly become a skeletal implant. Osseous ingrowth occurs with mature bone existing in the surface pores at approximately 1 year after implantation.2 At this point, the hard implant is essentially a fixed extension of the bone and is not subject to displacement, which occurs more frequently with the Silastic material.

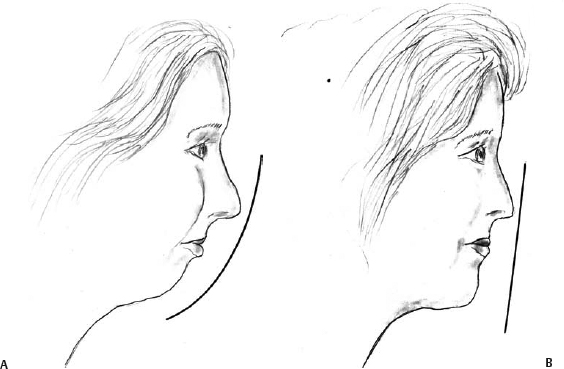

♦ Chin Augmentation

If a facial plastic surgeon were allowed to incorporate only one area of facial skeletal augmentation into his or her practice, that surgeon would be wise to choose the chin. Placement of such an implant in a patient with chin retrusion works wonders in improving appearance. Bringing the chin forward can balance the facial profile, changing what is a convex shape in the lower face to a straighter, more aesthetic one. Figure 9.1 illustrates this point. Augmentation of the chin can balance the appearance of a strong nasal profile. The large nose is made to look less imposing because it is balanced by more projection in the lower face. Chin augmentation is also a powerful tool in aging face surgery. When a retrusive chin is augmented, there is a lengthening of the entire jawline. The geometry of the cervicomental angle is altered, and a more aesthetic neck and jawline appearance emerges. Figure 9.2 illustrates this effect in a patient who underwent revision rhinoplasty. The only other procedure performed was the chin implant. The effect on the cervicomental angle is readily apparent.

A chin implant can also greatly improve the effect of a facelift in the properly selected patient. By lengthening the short jawline, the surgeon has a better framework on which to position the facial soft tissues. Figure 9.3 demonstrates the use of mental augmentation in a facelift patient with a retrusive chin. The lengthening of the jawline and forward pull on the submental skin clearly contributes to the positive quality of the result. Figure 9.4 illustrates how the chin implant may be used in a patient with a more normally projecting chin who has a very difficult neck and desires as much improvement as the surgeon can possibly give. In this instance, bringing the anterior projection of the chin forward creates the platform on which through submental liposuction and firm posterior and superior repositioning of the platysma muscle a significant change in the cervicomental angle can be established.

Operative Technique

A pertinent history and physical examination should be performed. In the course of this preoperative analysis, the physician may perceive that the chin is underprojected and that augmentation may be called for, even thought the patient may not realize this. In this case, the surgeon should examine the patient’s dental occlusion and ask about problems pertaining to temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function. Pain on chewing, popping or cracking noises emanating from the TMJ area with mouth opening or closing, or even chronic headache can all be signs that there is a problem with the patient’s bite. If this is the case, the patient requires referral to an oral/maxillofacial surgeon for evaluation of the relationship between the maxilla and mandible and perhaps orthognathic surgery.

Fig. 9.1 (A) Convexity of the facial profile is aesthetically undesirable. (B) A chin implant can help straighten the profile and improve appearance.

A complete set of photographs (front, oblique, and lateral views) should be taken and reviewed with the patient as part of the consultation. It is vital that these be shot with the patient’s head in level position to avoid misjudging the projection of the mentum relative to the rest of the face. The patient should be lined up in the Frankfort plane, whereby the top of the external auditory canal is at the same height as the inferior orbital rim. When looking at the soft tissues, this equates to the top of the tragus being at the same height as where the bony orbital rim is seen or palpated to be. The lateral view is the most powerful tool to demonstrate to the patient, when appropriate, that the chin is retrusive and that an implant may be helpful. Beforeand-after views of patients for whom the surgeon has performed such an implant will serve well to demonstrate the profound effect the procedure can have. Front and lateral views are helpful in assessing the width of the chin and also the chin but also to help fill in this sulcus. It is important to looking at the groove or depression that occurs along the talk with the patient about this effect as well as the estijawline anterior to the jowl and is termed the prejowl mated change in the width of the chin that will result from sulcus. A chin implant can be fashioned to not only project the procedure.

Fig. 9.2 (A) Before and (B) after revision rhinoplasty with a Gore-Tex chin implant.

Fig. 9.3 (A) Before and (B) after facelift, Gore-Tex chin implant, and brow lift. Chin augmentation enhances the facelift result.

Fig. 9.4 (A) Before and (B) after facelift, Gore-Tex chin implant, and upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasty.

Selection of Size

Choosing the best implant size is a crucial factor in delivering a result that the patient will enjoy. It is easy for the inexperienced surgeon to use chin projection on the lateral view to determine how large an implant to use, only to realize later that a different size should have been used. In general, the patient’s overall size and especially head size help determine how large an implant to use. For example, a large implant, unless extensively modified (carved down), rarely looks good on a small woman, regardless of how retrusive the mandible is. Whereas such a patient could end up with a beautiful improvement on the lateral view, she could also have an excessively widened chin on the frontal view, which happens to be the only view she looks at in the mirror each day. In such a case, the patient would be justifiably unhappy and the surgeon headed back to the operating room to exchange the implant for a more suitable size.

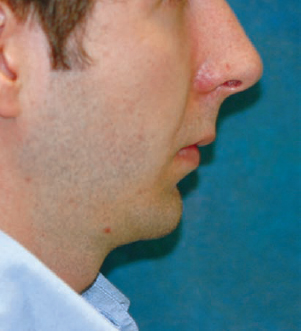

Another error that can be made is to place an implant in a patient whose chin is retrusive but possesses a strong forward curve. These patients usually have occlusal abnormalities and require orthognathic surgery rather than simple chin augmentation (Fig. 9.5). Placement of an implant in this setting might result in overprojection of the chin resulting in a shelf-like effect that is unaesthetic. In both of the above scenarios, the point is that the surgeon must consider the chin, jawline, and neck from all views and in three dimensions to anticipate the effect of the implant and make the correct decision.

Exposure

The patient is marked, prepped, and draped in a sterile fashion. Chin implants may be placed through intraoral or submental incisions. Each approach has its advantages and drawbacks. An intraoral approach avoids an external scar. A submental approach allows for a truly sterile procedure, by preventing oral contaminants from coming into contact with the implant and surgical site. A submental approach also avoids disruption of the labiomental crease and the possibility of labial insufficiency should healing in the area be less ideal than expected. For the latter two reasons, the authors prefer the submental approach, which is described below.

Fig. 9.5 Patient with mandibular retrusion who exhibits a normal forward chin curve. Orthognathic surgery may be required to balance the profile. A chin implant may actually worsen his appearance.

An existing submental crease is selected for the incision site, if one is available. In younger patients without a defined crease, the surgeon need simply have the patient bend his or her head downward toward the chest, and the future crease site will emerge. It is important to realize that the implant will pull the submental skin forward, and for this reason, the incision is marked slightly posterior to the desired eventual location. When several creases exist, which is usually the case, one of the more posterior ones may yield a less conspicuous scar. The eventual location of the incision site after the implant has been placed should be well posterior to the anterior point of the chin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree