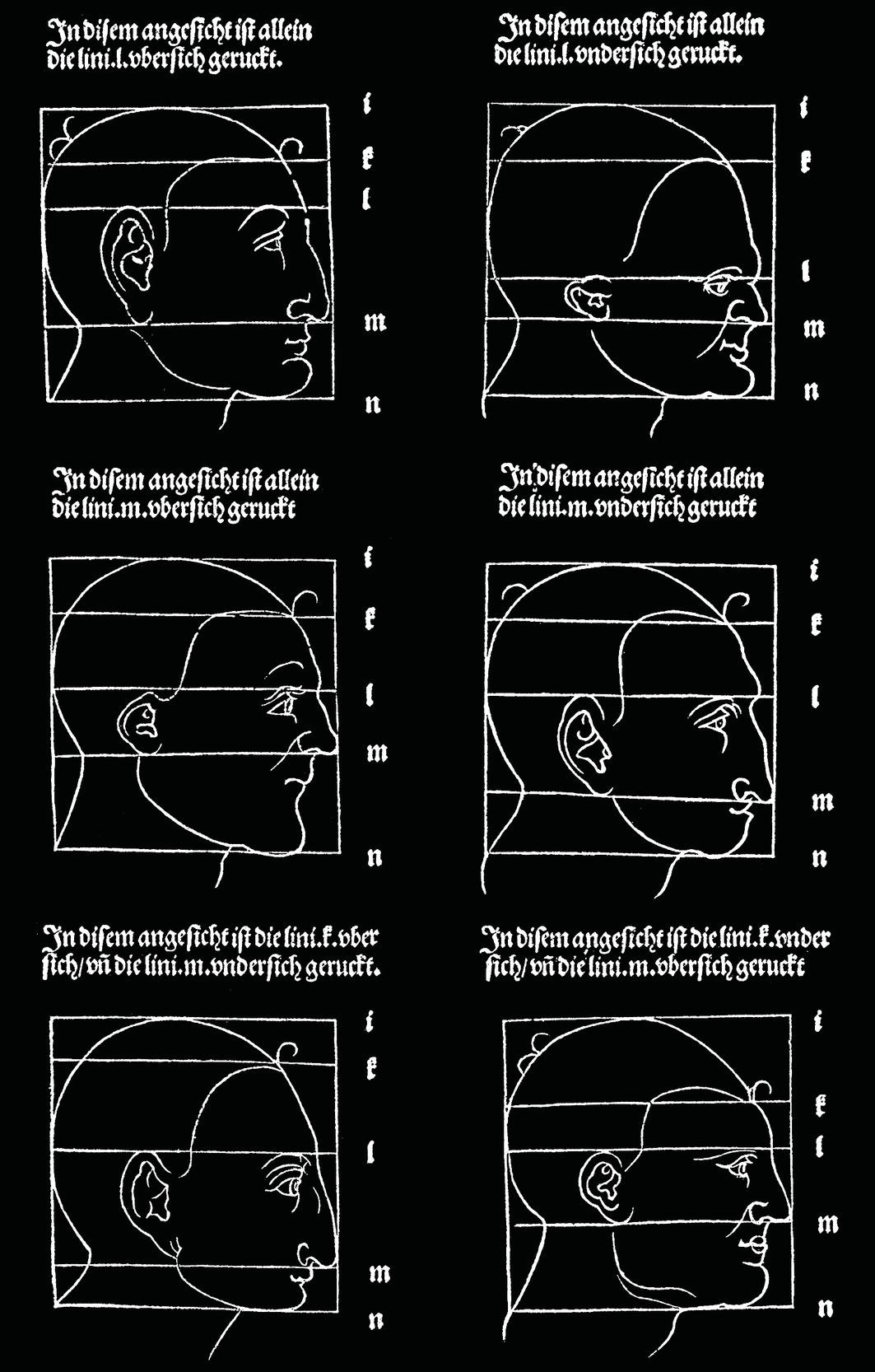

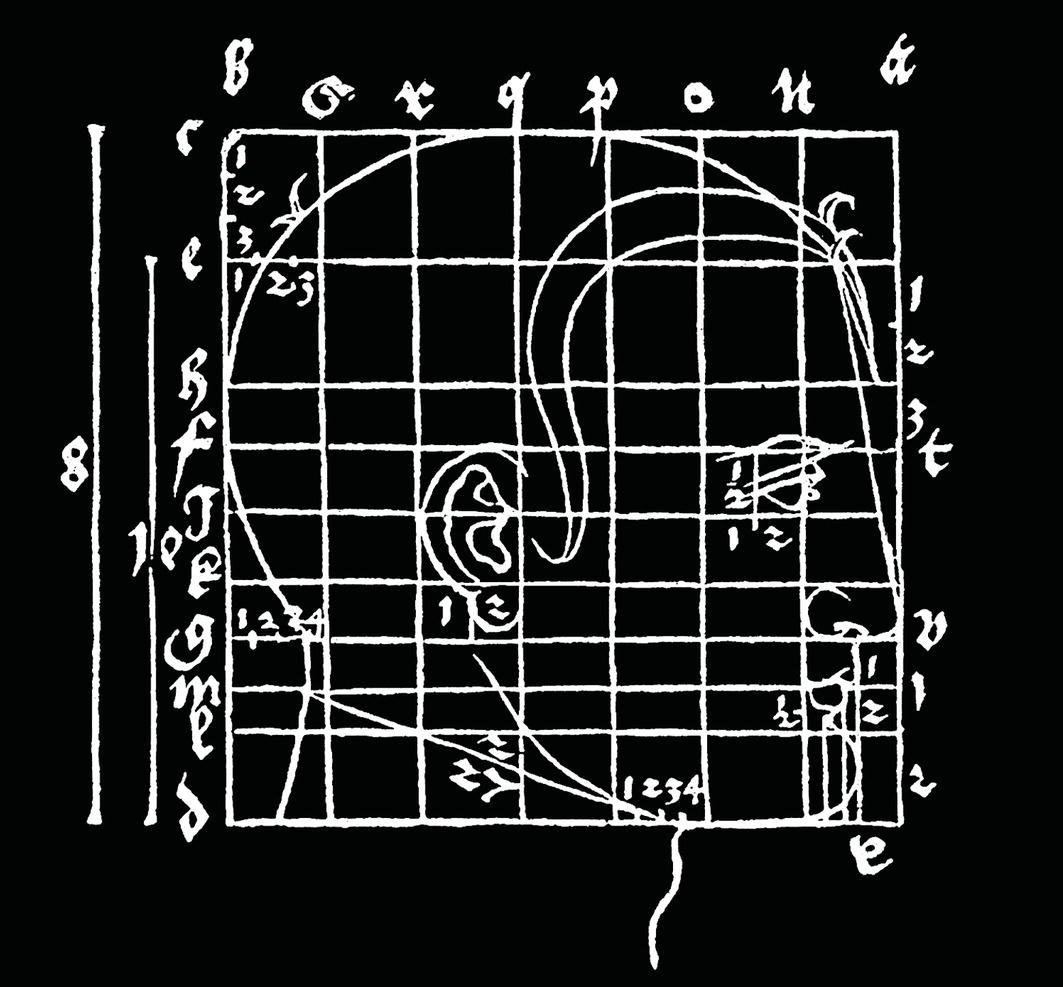

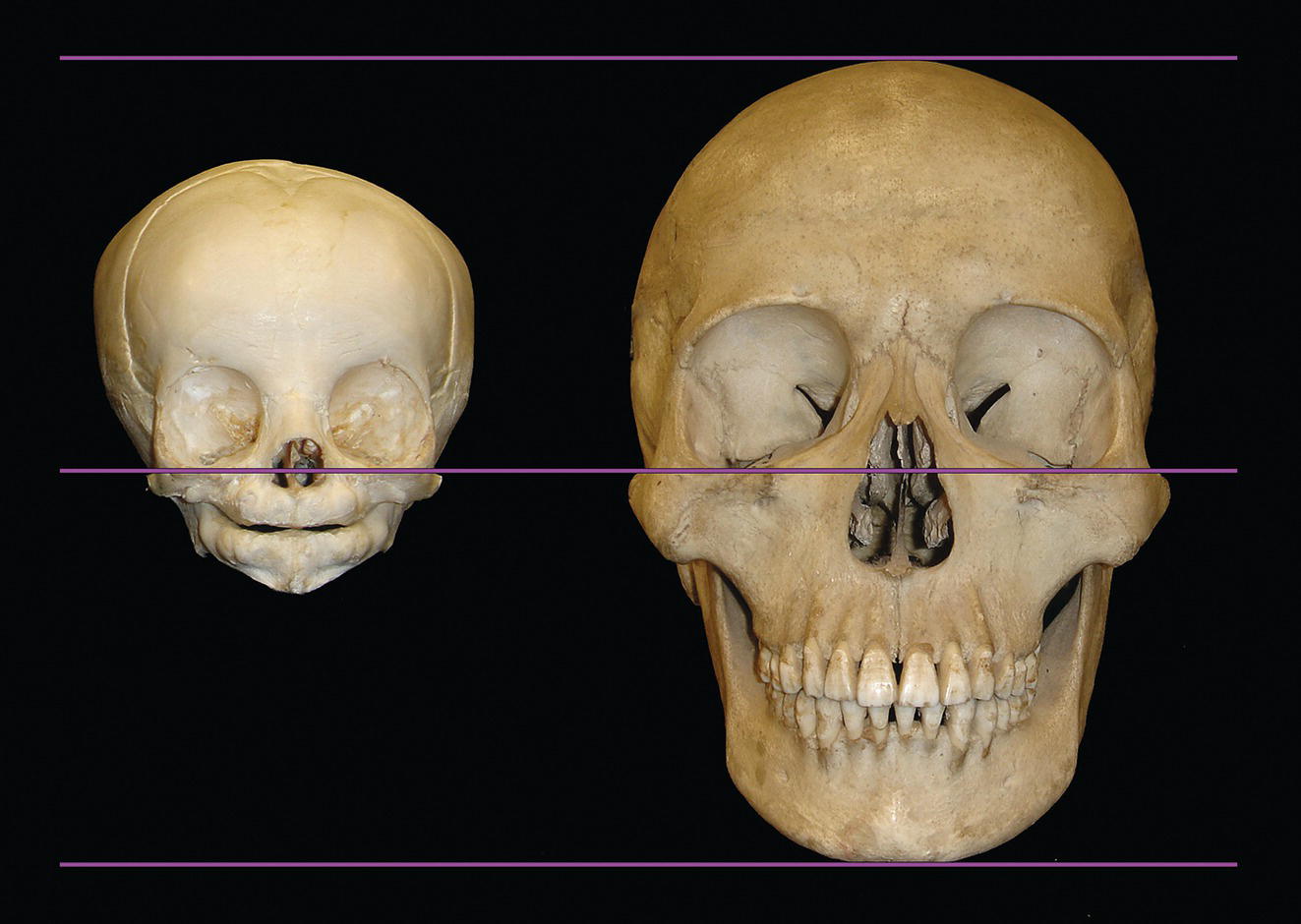

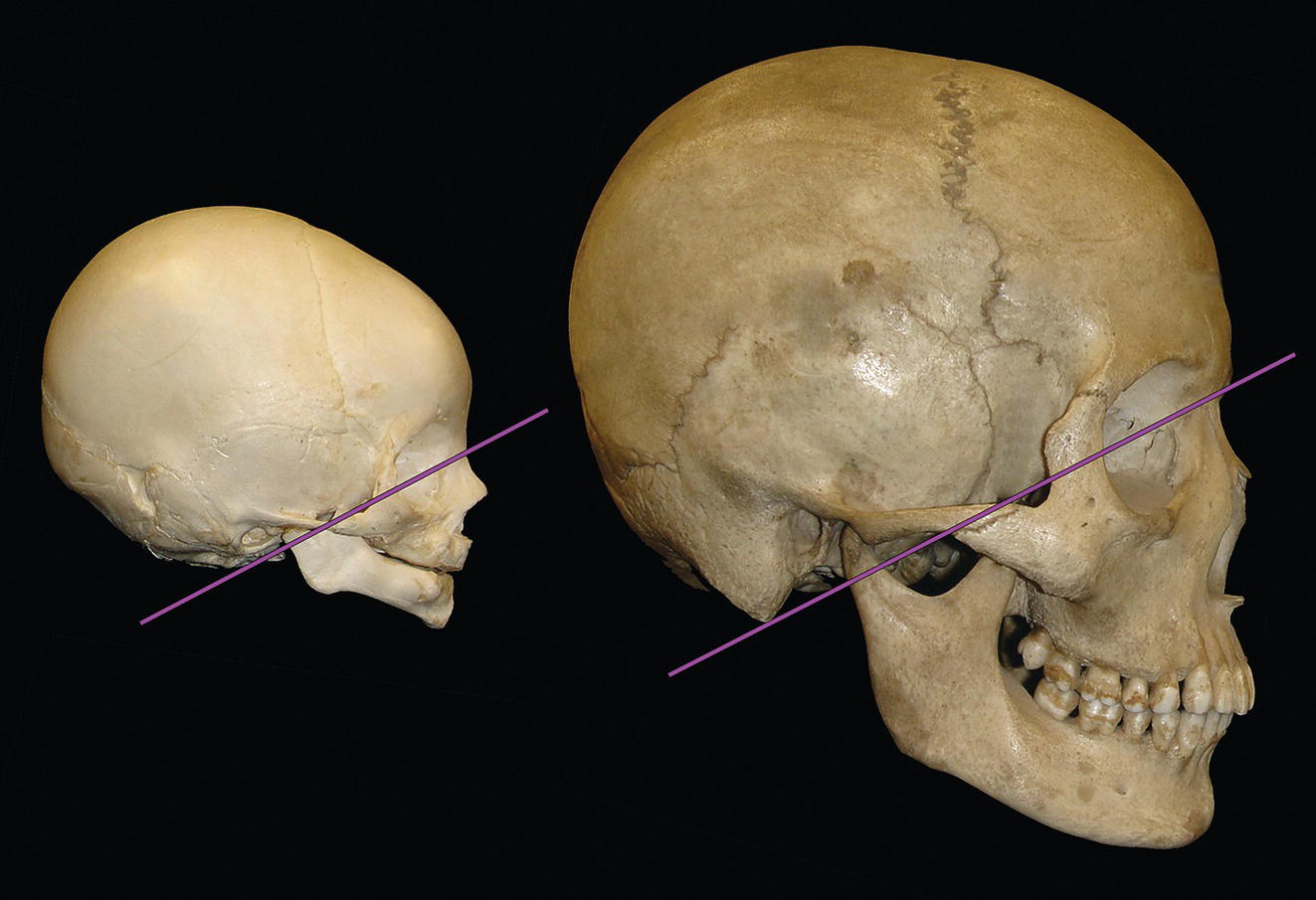

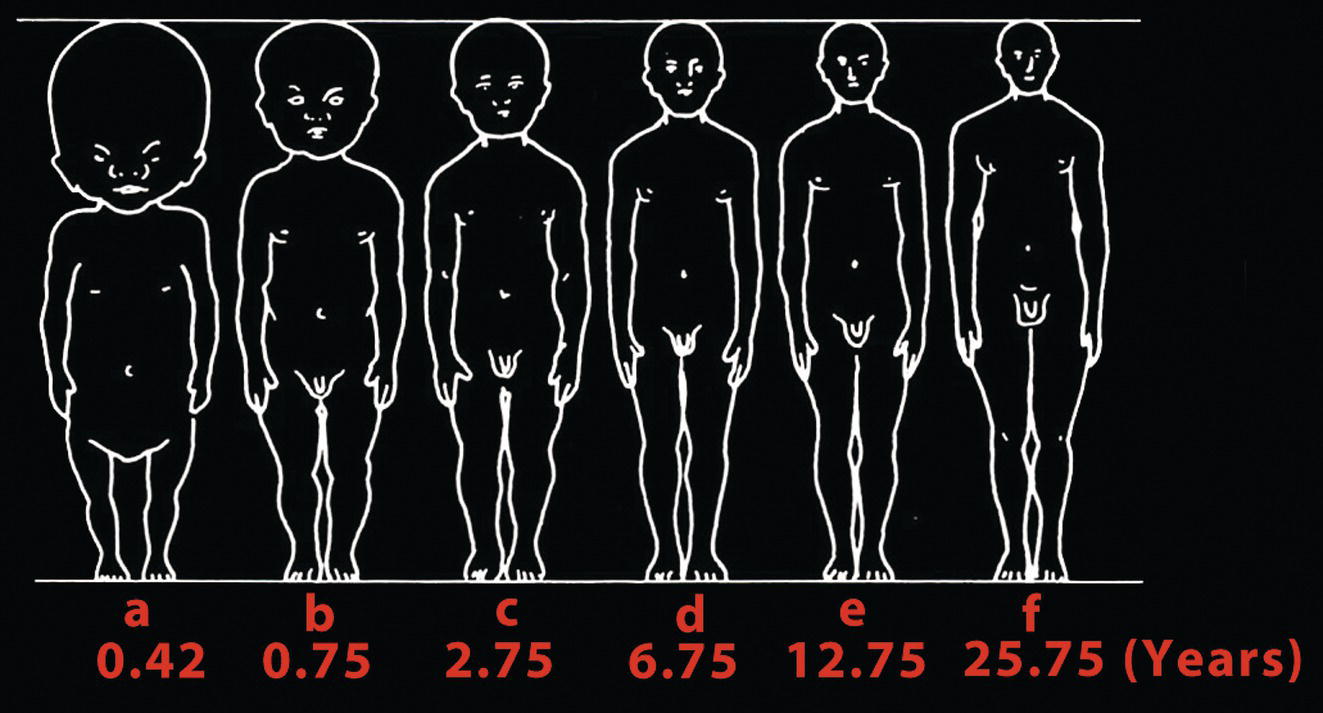

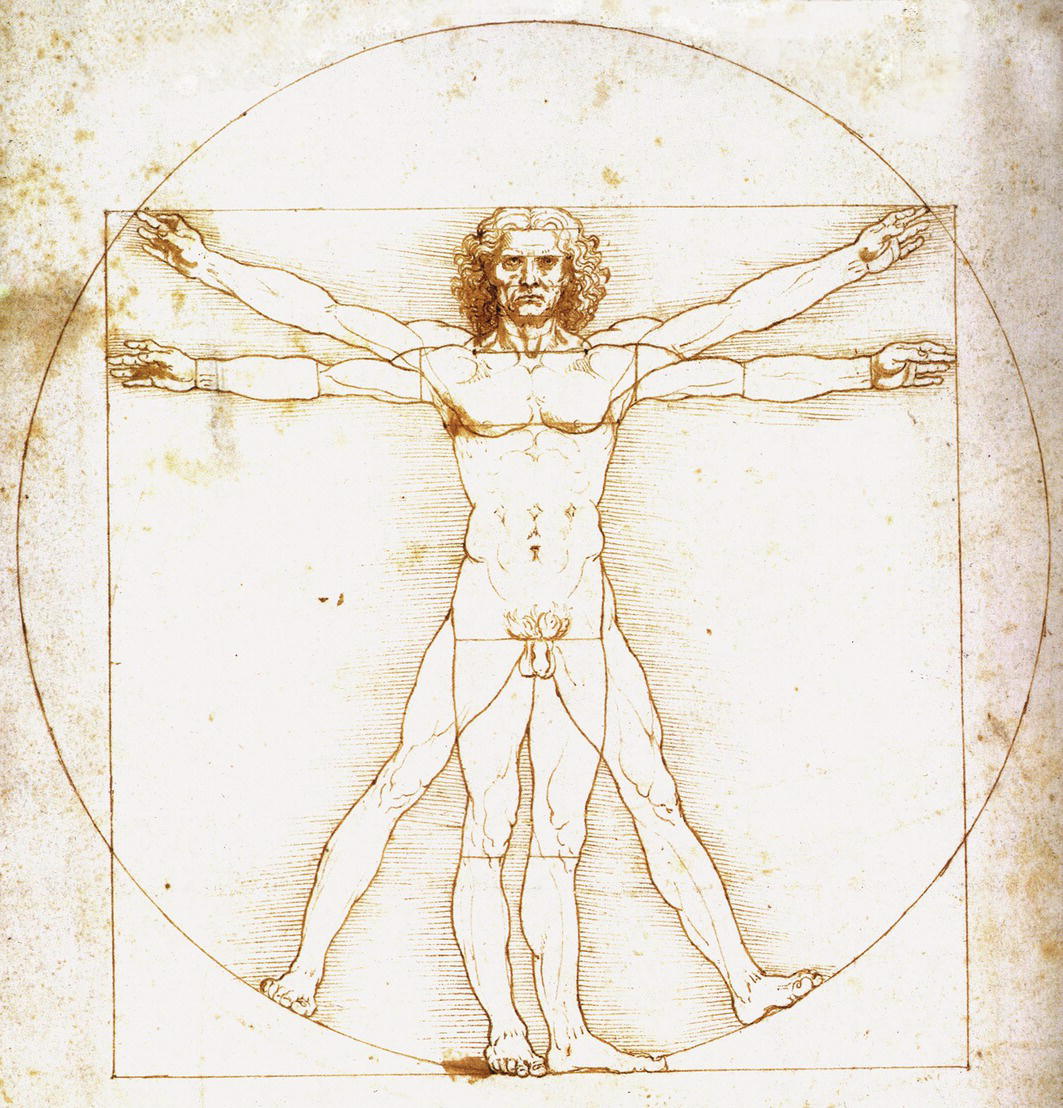

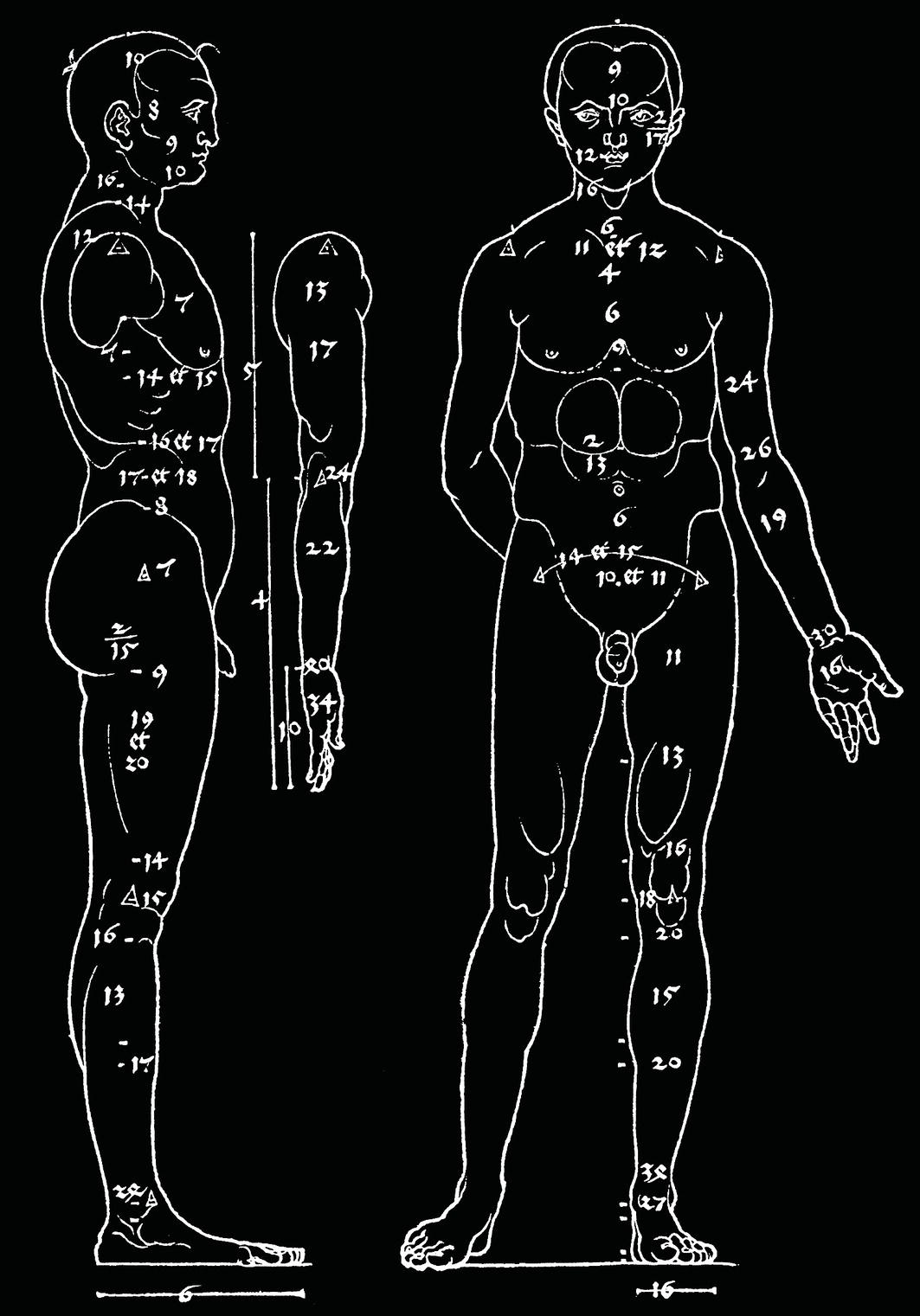

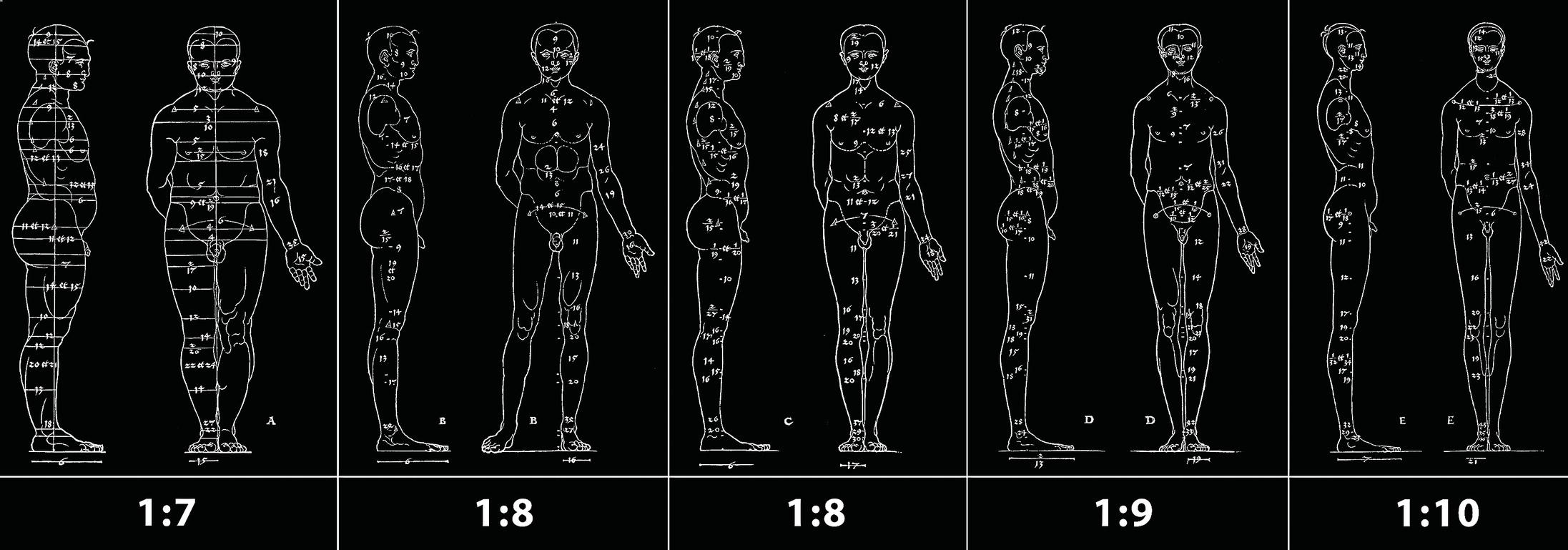

‘… never depart from the guiding line of proportion. Harmony or disharmony does not lie within angles, distances, lines, surfaces or volumes. They arise from proportion’. Dr Paul Tessier (1917–2008),1 French surgeon and acknowledged pioneer of modern craniofacial surgery Proportion may be defined as the ideal, attractive relationship between one part to another or between the parts of a whole (Latin proportionem: ‘comparative relationship’). There is no absolute correlation between a well‐proportioned face and facial beauty. In the essay ‘Of Beauty’ (1625), Sir Francis Bacon wrote: ‘There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion’.2 However, a well‐proportioned face will be acceptable, even if not always beautiful. In the sixteenth century, Albrecht Dürer explained that although the concept of facial beauty was immersed in subjectivity, the assessment of facial proportions could be undertaken objectively.3 He maintained that disproportionate human faces were unattractive (Figure 9.1), whereas proportionate features were acceptable, even if not always beautiful (Figure 9.2).4 Therefore, the appropriate aim of objective clinical examination is the detection of facial disproportions. Individuals may vary quite considerably from population norms, but by understanding average proportions the clinician will be able to detect where the differences occur. By evaluating overall facial proportions, followed by the proportion of each respective facial part to the whole craniofacial complex, the clinician will be able to detect both the source(s) of the disproportional face and the degree of variance from the acceptable norm (i.e. average for the respective population). Figure 9.1 Vertical facial disproportions. (Modified from Dürer4.) As always in clinical examination, it is important not to ‘miss the wood for the trees’. Clinical evaluation must begin with overall craniofacial proportional relationships and gradually work towards more detailed analysis. Figure 9.2 Ideal craniofacial proportional relationships. (Modified from Dürer4.) A useful starting point for the clinical evaluation of craniofacial proportional relationships, which may be potentially significant in treatment planning, is that of the craniofacial height to standing height proportion.5 The first significant known study of human proportions was undertaken in the fifth century bc by the Greek sculptor Polycleitos, of Argos. It is generally acknowledged that the work of Polycleitos was used by other sculptors as demonstrating the ‘ideal’ proportions of a man. The Canon of Polycleitos refers to both the book written by Polycleitos, of which no copies exist, and the Roman marble copies of his original bronze statue described as the Canon, otherwise known as the Doryphoros (Spear‐bearer) (Figure 9.6). Therefore, the ‘ideal’ human proportions suggested by Polycleitos may only be gleaned from examination of Roman copies of the Doryphoros.6,7 The craniofacial height to standing height proportion of the available marble copies of the Doryphoros is 1/7.5. Figure 9.3 Proportional differences in the size of the neonatal and adult skull. In the neonate, the face and jaws are relatively underdeveloped in comparison with the adult. Figure 9.4 Relative sizes of the cranium and facial skeleton in the neonatal and adult skull. The extent of postnatal growth of the face and, in particular, the jaws exceeds that of the cranial structures. Figure 9.5 Schematic representation of the changing proportions of head size to body size during normal growth and development. (Medawar and Le Gros6/Oxford University Press.) Figure 9.6 Doryphoros (‘Spear‐bearer’). In the fifth century bc, Polycleitos wrote the Canon, in which he laid down the guidelines for the ideal proportions of the human body. In this statue, also often referred to as the Canon, Polycleitos created the archetype of the Greek ideal of male beauty. (Roman copy after the Greek original; Marble, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.) In the late fourth century bc, the prolific Greek sculptor Lysippos (c. 330 bc) is thought to have revised the Canon of Polycleitos, establishing a new canon in the use of eight heads to standing height. This is evident from inspection of the Roman marble copy of the Apoxyomenos (‘The Scraper’, depicting an athlete scraping off olive oil from his body, commonly undertaken following sporting activities in ancient Greece) (Figure 9.7); it is also evident in the famous statue by the Greek sculptor Leochares (a contemporary of Lysippos), the Apollo Belvedere, in the Vatican Museum (Figure 9.8). Figure 9.7 Apoxyomenos (‘The Scraper’) of Lysippos. (Roman copy after the Greek original; Vatican Museum.) Figure 9.8 Apollo Belvedere of Leochares. (Roman copy after the Greek original; Vatican Museum.) The Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, better known simply as Vitruvius, lived in the first century bc, and is thought to have dedicated his 10‐volume treatise De Architectura (‘On Architecture’) to the emperor Augustus Caesar in about 25 bc. In the first chapter of Book III, entitled ‘On symmetry in temples and the human body’, he defined proportion as ‘a correspondence among the measures of the members of an entire work, and of the whole to a certain part selected as standard’.8 Vitruvius believed that Nature’s designs were based on universal laws of proportion and therefore that the human body’s proportions could be used as a model of natural proportional perfection. He described how ancient artists and sculptors, particularly the Greeks, had examined many examples of ‘well‐shaped men’ and discovered that their bodies shared certain proportions. Hence, it seems that anthropometry was used by the Greeks in attempting to determine ‘ideal’ human proportional relationships. Vitruvius wrote that ‘the human body is so designed by nature that the face, from the chin to the top of the forehead and the lowest roots of the hair, is a tenth part of the whole height’.5,8 The facial height to standing height proportion of 1/10 corresponds to a craniofacial height to standing height proportion of 1/8.5 Figure 9.9 Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (Homo vitruvianus), (c. 1490). This famous figure shows that the proportionate human form fits perfectly in perfect geometric shapes, the circle and the square. The navel forms the centre. It is based on the ‘ideal’ male proportions described by the Roman architect Vitruvius [with some of Leonardo’s modifications, particularly in moving the square downwards, off‐centre in relation to the circle]. (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice) The scientifically enquiring minds of the Renaissance were no longer interested in blindly following the classical ‘ideal’, and began to study human anatomy and record human proportions. Adapting the work of Vitruvius with his own anthropometric research, the great Renaissance artist and thinker Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) provided the Renaissance canons of proportion. He described the ‘ideal’ craniofacial height to standing height proportion as 1/8.9 In the late fifteenth century Leonardo drew the figure of Vitruvian Man (Figure 9.9), based on guidelines described by Vitruvius and his own anthropometric research, demonstrating the importance of proportions in the human form. He demonstrated that the ‘ideal’ human body fitted precisely into both a circle and a square, thus illustrating the link that he believed existed between perfect geometrical forms and the perfect body. The distance from the hairline to the inferior aspect of the chin is described as 1/10 of a man’s height. The distance from the top of the head to the inferior aspect of the chin is 1/8 of a man’s height.9,10 Figure 9.10 Albrecht Dürer’s Man of Eight Head‐Lengths. (Modified from Dürer4.) Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), perhaps the most significant artist of the German Renaissance, wrote a treatise on human proportions. The first of the Four Books on Human Proportion, published posthumously, described the ‘ideal’ man of Eight Head‐Lengths (Figure 9.10).4 However, Dürer described the craniofacial height as ranging from 1/7 to 1/10 of standing height depending on the individuals’ stature; the thinner the individual the closer to 1/10 the proportion (Figure 9.11). In the twentieth century, and extending into the twenty‐first, Leslie Farkas undertook a large body of research into the anthropometry of the human head, providing anthropometric data for adult North American Caucasian and other ethnic group norms.11 The craniofacial height to standing height proportion may be calculated from the original anthropometric data provided by Farkas et al.12 From these original anthropometric data, the craniofacial height to standing height proportion in young adult males (age range 19–25 years) is found to be 1/7.7 (range 1/7.4 to 1/8.1), and in young adult females (age range 19–25 years) is found to be 1/7.6 (range 1/7.2 to 1/7.9).5 A study was undertaken to test the validity of the classical, neoclassical and modern anthropometric‐based proportional canons for the craniofacial height to standing height proportion, and to compare the results with the judgement of perceived attractiveness of the lay public and clinicians.5 The results of the attractiveness study lend support to both the classical ideal of 1/7.5 and the Renaissance ideal of 1/8. The results of this study, based on layperson‐ and clinician‐perceived judgements of attractiveness, generally validate the anthropometric data. In this study it was found that a proportion of 1/7.5 was perceived as the most attractive, with 1/8 a close second. The images regarded as most attractive by the participants had a mean craniofacial height to standing height proportion of 1/7.8 (minimum = 1/7 and maximum = 1/8.5). In addition, the mean rank preference score was found to be minimal for a craniofacial height to standing height proportion of 1/8 and increased when the craniofacial height to standing height proportion moved away from 1/8 in either direction. The ranking of the images was not influenced by the observer’s age, sex, ethnicity or professional status, providing support to the available evidence for the universality of judgements of attractiveness.13 Figure 9.11 Dürer described the craniofacial height as ranging from one‐seventh to one‐tenth of standing height depending on an individual’s stature; the thinner the individual the closer to one‐tenth is the proportion. He considered types B and C (one‐eighth proportional ratio) as closer approximations to the ‘ideal’. The figures were based on anthropometric data collected by the measurement of ‘many individuals’ and coordinated into ‘types’. (Modified from Dürer4.) Patients presenting with craniofacial or dentofacial anomalies are, by definition, not average. Therefore, in treatment planning, the use of mean craniofacial measurements based on population norms, though extremely important, must be used in conjunction with, and guided by a thorough understanding of facial proportional relationships. The proportion of vertical craniofacial (head) height, and vertical facial height, to standing height has important clinical implications. If the vertical craniofacial proportions of a patient are to be altered with surgery, the treatment plan must take into account the proportion of the patient’s total face height to their standing height. The use of absolute numerical values of facial measurements rather than facial proportions may be misleading, as the vertical facial height of a patient who is 1.8 m (6 ft) tall will be different from that of a patient who is 1.5 m (5 ft) tall.7 It is recommended that in planning treatment to alter any aspect of craniofacial or facial height, the ideal craniofacial height to standing height proportion of 1/7.5–1/8, with a range from 1/7 to 1/8.5, be considered.5 Classical, Renaissance and neoclassical facial canons describe vertical proportional relationships with the vertical craniofacial bisection, the vertical facial trisection and the vertical craniofacial tetrasection. The head may be vertically divided into halves, with the eyes positioned on a line constructed halfway between the top of the head (vertex) and the inferior aspect of the chin (soft tissue menton). The lower facial third may be further subdivided into two equal parts: This proportional canon was described by the Roman architect Vitruvius and popularized by Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 9.13); the face may be vertically divided into thirds (Figure 9.14):

Chapter 9

Facial Proportions

Introduction

Craniofacial height to standing height proportion

Classical, Renaissance and neoclassical proportional canons

Anthropometric data

Attractiveness research

Clinical implications

Vertical Facial Proportions

Vertical craniofacial bisection (Figure 9.12)

Vertical facial trisection (Vitruvian trisection)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree