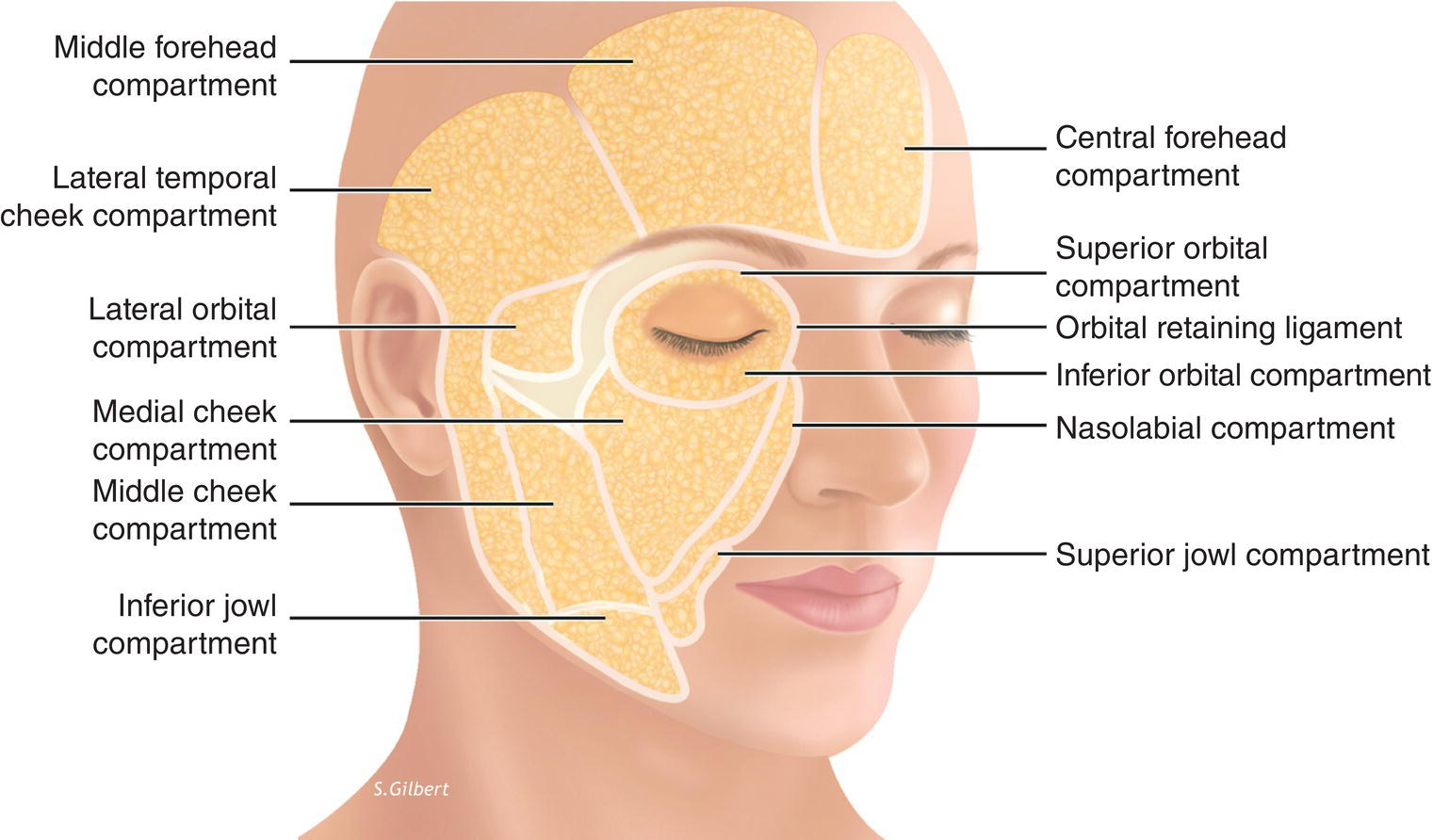

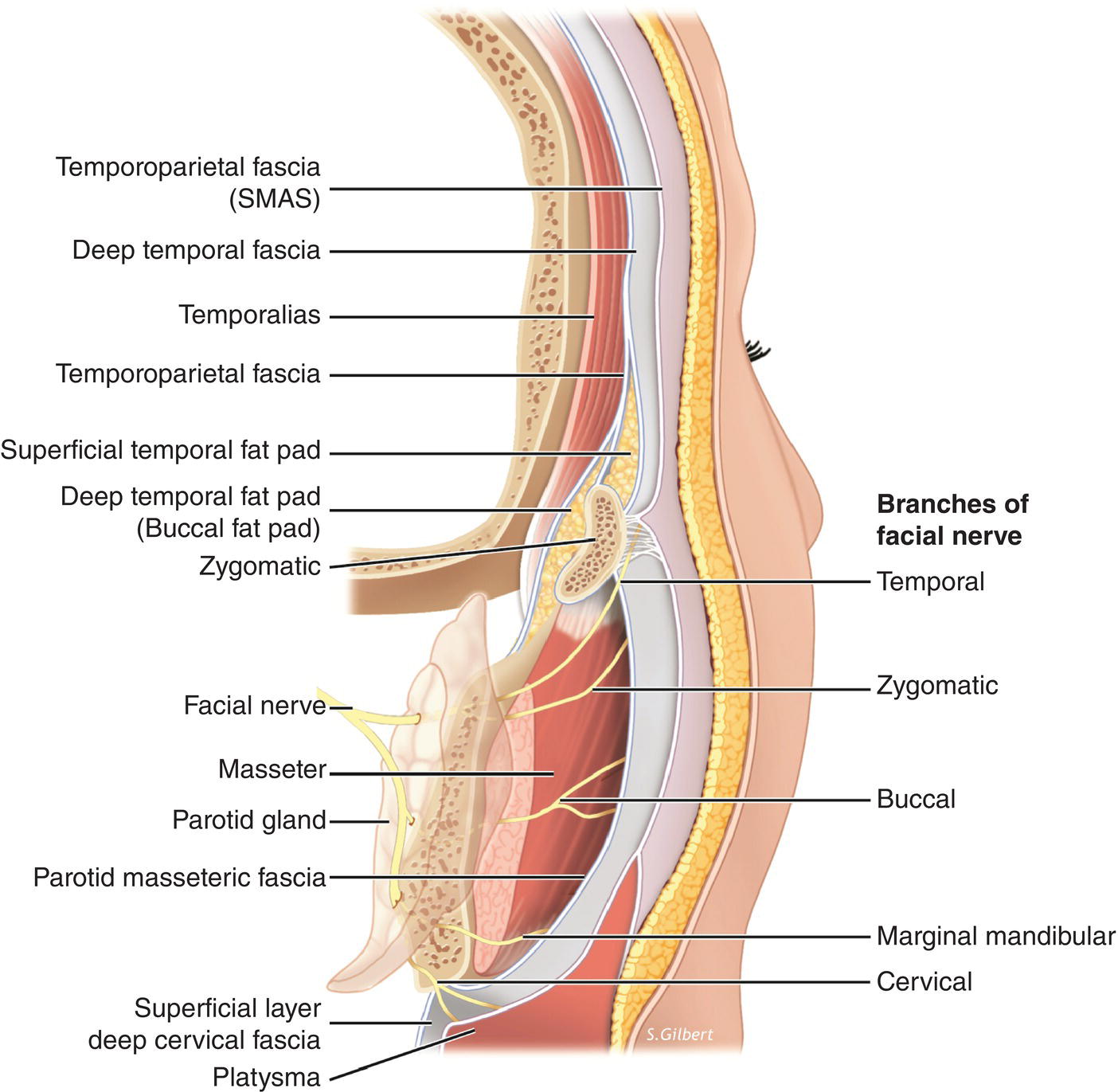

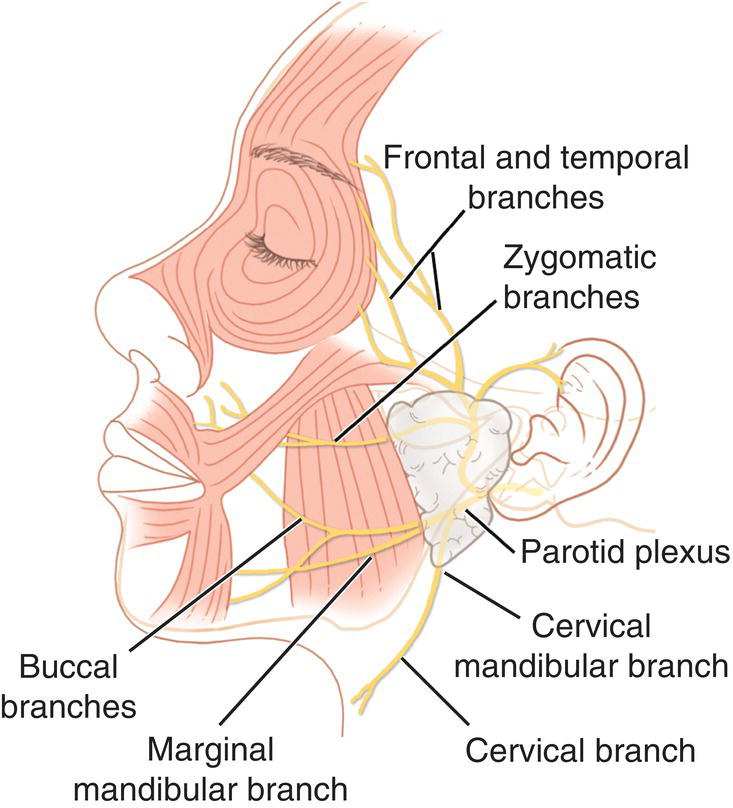

1 Timothy Osborn1,2 and Bradford M. Towne1 1 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Boston University, Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine, Boston, MA, USA 2 Private Practice, C.M.F.‐Cranio‐Maxillofacial Surgery Associates, Boston and Somerville, MA, USA A comprehensive understanding of facial anatomy is a critical component of any facial esthetic procedure. A comprehensive review of facial anatomy is beyond the scope of this text, and this chapter will focus on regional anatomy as it pertains to minimally invasive rejuvenation. All aging changes manifest in different ways for each individual patient, thus an understanding of the changes pertinent for the individual must be understood when considering patient evaluation, planning, and treatment. Incorporating the anatomic effects of aging into the treatment plan will allow the treating provider to target the specific areas to reverse those signs of aging. The face has a layered structure that is best described from superficial to deep and includes the following: skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial musculo‐aponeurotic system (SMAS), deep fat, and deep fascia/periosteum. This architecture is preserved throughout the head and neck, with some areas further subdivided into fascial or fat compartments that will be addressed individually. These different compartments and layers may carry different names as they cross anatomic barriers making nomenclature difficult. A special section of the chapter will focus on these terms and clarify some key relationships. The skin layer is divided into epidermis and dermis. The epidermis is the outermost layer and contains a continually renewing, keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium. The epidermis is anchored to the underlying dermis by hemidesmosomes and anchoring fibrils at the basement membrane. This dermal–epidermal junction provides the mechanical support to the epidermis and acts as the barrier to chemicals and other substances. Immediately below the epidermis, the dermis is the connective tissue composed of collagen, elastin, ground substance, the pilosebaceous unit, and accommodates a complex neurovascular network. The dermis gives the skin it’s pliability, elasticity, and tensile strength. The dermis is divided into two components: the papillary and reticular dermis. The papillary dermis is the thin layer adjacent to the epidermal papillae and sits atop the thicker reticular dermis. The papillary dermis consists of loose connective tissue, fibroblasts, immunocytes, and a capillary network. The reticular dermis is thicker and is composed of more densely organized collagen (which runs horizontally) and elastin fibers (which are loosely arranged). Variation in the thickness of the dermis is what accounts for regional variation in skin thickness. Ground substance is composed of glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and has a remarkable capacity to hold water. These different subcutaneous arrangements vary in thickness between individuals of different ages, ethnicities, and lines of demarcation into distinct compartments [1]. There is heterogeneity of the facial fat in these compartments, with each compartment having different adipocyte morphology, and extracellular matrix [2]. These different compositions provide unique and specific mechanical and histiochemical properties yet there is little known about the characteristics of facial fat tissue and how that relates to facial aging. The subcutaneous fat is immediately deep to the dermis and is a discrete anatomic plane superficial to the SMAS. There is also a deeper layer of facial fat below the SMAS that will be discussed separately. The superficial layer of fat, or subcutaneous fat, can be further subdivided into two different arrangements with different microstructures. In the medial and lateral midface, temple, neck, forehead and periorbital areas, the adherence of the underlying structures to the skin is loose and easily separated from the skin [3]. The fat is classified as “structural” with a meshwork of fibrous septa enveloping lobules of fat cells that act as small pads with specific viscoelastic properties [4]. In the perioral, nasal, and eyebrow regions, there is a stronger linkage between the facial muscles, the collagenous meshwork surrounding the adipocytes, and the skin making any blunt dissection difficult. The collagenous and muscular fibers directly insert into the skin and connect the skin to the underlying muscles of facial expression. The fat is classified as “fibrous” with a meshwork of intermingled collagen and elastic fibers as well as muscle fibers. The superficial fat compartments are partitioned as distinct anatomic compartments (nasolabial, jowl, cheek, forehead/temporal, and orbital [Figure 1.1]). Figure 1.1 The superficial fat compartments of the face. The nasolabial fat compartment lies medial to the cheek fat and while separate, overlaps the jowl fat. The orbicularis retaining ligament (ORL) represents the superior border and the lower border of the zygomaticus major and is adherent to this compartment. The jowl fat is adherent to the depressor anguli oris, bound medially by the lip depressors, and inferiorly is a membranous fusion with the platysma muscle in the area of the mandibular‐cutaneous ligament [5]. The cheek fat compartments contain three distinct compartments: the medial, middle, and lateral temporal cheek fat. The medial cheek fat is a small compartment lateral to the nasolabial fold (NLF), bordered superiorly by the ORL and lateral orbital compartment, and the jowl fat lies inferior. The middle cheek fat is a larger compartment found anterior and superficial to the parotid gland. At its superior portion, the zygomaticus major is adherent at a confluence of septa corresponding to what has been described as the zygomatic ligament [6]. The lateral temporal‐cheek compartment is the most lateral compartment of the cheek fat. This fat lies immediately superficial to the parotid gland and connects the temporal fat to the cervical subcutaneous fat. There is an identifiable barrier medially called the lateral cheek septum which is consistent with the subcutaneous extension of the parotid‐cutaneous ligament. The subcutaneous fat of the forehead is composed of three compartments. The central compartment is midline and abuts the nasal dorsum inferiorly, and the middle temporal fat laterally on either side. The middle temporal fat borders the orbicularis retaining ligament inferiorly and the superior temporal line laterally. Just lateral to this is the lateral–temporal cheek fat described earlier. The orbital fat compartment consists of three compartments around the eye. The most superior compartment is bounded by the orbicularis retaining ligament as it courses around the superior orbit and sits immediately below the middle‐temporal fat. The inferior orbital fat lies immediately below the lower lid tarsus and is bound by the lower limb of the orbicularis retaining ligament. The lateral orbital fat lies below the inferior temporal septum, above the superior cheek septum just above the zygomaticus muscle. The lateral orbital fat compartment interdigitates superiorly and laterally with the lateral temporal cheek fat, and above the middle cheek fat. Explanations of the facial and cervical fasciae are often complex, inconsistent, and very confusing. The concept of the SMAS was first introduced by Mitz and Peyronie, and while it is a discreet anatomic layer surgically, there are many who debate or seek to adequately define the layer [3, 7]. The SMAS is an organized and continuous fibrous network connecting the facial muscles with the dermis and consists of a three‐dimensional architecture in two different architectural models as described by Ghassemi. Type 1 is seen in the posterior part of the face and is a meshwork of fibrous septa that envelops lobules of fat cells. The interconnecting fibrous network is anchored to the periosteum or connected to the facial mimetic muscles and has dynamic properties. This morphology is found in the parotid, zygomatic, infraorbital regions, and just lateral to the nasolabial fold. Type 2 is a meshwork of collagen and elastic fibers intermingled with fat cells and muscle fibers that reach up to the dermis of the skin. This SMAS morphology is found in the upper and lower lip/perioroal region where the action of the facial mimetic muscles has a direct relationship to movements of the lip/perioral skin. The subcutaneous zone of the face is divided into superficial and deep strata by the facial muscles and superficial fascia which serve as their origin. In the neck, the space of the superficial fascia is occupied by the platysma muscle and it’s thin investing fascia. The SMAS and the temporoparietal fascia serve as the superficial facial fascia of the face (Figure 1.2). Figure 1.2 Relationship of the facial fasciae in the lateral cheek/temporal region. The figure demonstrates the complex relationship between the fascia, facial nerve, and the often confusing nomenclature of the continuous layers. The continuation of the temporoparietal fascia layer medial to the superior temporal line is the galea aponeurotica and fascia investing the forehead musculature. The galea is densely adherent to the overlying dermis with maximal adherence at the transverse forehead rhytids, while the undersurface is separated from the underlying periosteum. Inferiorly, the deep galeal fascia splits to line the deep surface of the frontalis and a deeper layer is adherent to the underlying periosteum over the lower 2–3 cm of the forehead. This fascial construct creates a glide‐plane space between the fixation point at the trichion and the lower fusion of the galea to the pericranium such that contraction of the frontalis elevates the brow. A detailed description of the deep fascial layers of the face and neck are beyond the scope of this chapter, but understanding of the superficial layer of deep cervical fascia is pertinent. This layer of investing fascia is deep to the platysma muscle, continues above the mandible as the parotid‐masseteric fascia, above the zygomatic arch as the deep temporal fascia, and above the superior temporal line as the pericranium. During the transit of this deep layer, there are many subdivisions and extensions that invest muscles, transit vessels, nerves, and lymphatics, and create anatomic potential spaces. The facial mimetic muscles are a complex balance of elevators, depressors, abductors, adductors, sphincters, that allow for facial expression, and certain facial functions. These muscles originate from the underlying soft tissues (SMAS) and insert into the skin, not to move the body, but to move the skin and underlying structures. The actions of these muscles assist in mastication, vision, smell, respiration, speech, and communication. These muscles are innervated by the extracranial branches of the facial nerve (Figure 1.3). Figure 1.3 The relationship of the facial nerve to the underlying facial musculature. It is easiest to discuss the muscles in anatomic groups. In the upper face, it is difficult to demarcate specifically the muscles of facial expression precisely from surface anatomy given the degree of overlap. The frontalis muscle comprises the only muscle responsible for brow elevation, and it forms transverse forehead rhytids. The frontalis originates from the broad galea aponeurotica which anchors on the posterior nuchal line and is fixed to the underlying pericranium of the calvarium. Activation of the muscle only moves the frontal portion to raise the brow and creates transverse forehead rhytids. This muscle has two halves and extends vertically downward to insert in the dermis at the eyebrow just above the supraorbital rim and glabella. The muscle lies at a uniform depth beneath the skin of the forehead, usually 3–5 mm deep. In the midline, there is no muscle, only a connecting fascial band or aponeurosis separating the two halves. The frontalis is counterbalanced by the glabellar complex (corrugators supercilii, procerus, and depressor supercilii) and orbicularis oculi muscles, all of which serve as the depressors of the brow. The glabellar muscles consist of the paired corrugator supercilii, depressor supercilii, and the procerus. The corrugators originate from the frontal bone near the superior and medial portions of the orbital rim. They pass through the galea fat pad before penetrating the frontalis and orbicularis to insert in the dermis. There are transverse and oblique heads of the muscle; the transverse head travels superolateral to insert in the dermis above the middle of the eyebrow, and the oblique head terminates in the dermis just medial to the brow. The oblique head acts with the other brow depressors forming oblique rhytids, and the transverse head results in medial brow displacement with accompanying vertical and oblique rhytids. The depressor supercilii originates from the bony prominence near the medial canthus and courses directly upward to insert in the skin of the medial brow. The procerus is a pyramidal muscle that originates in the lower nasal bone and extends vertically and inserts into the skin between the eyebrows merging with the frontalis. It is a depressor and forms a horizontal glabellar rhytid. The orbicularis oculi muscle is the sphincter muscle encircling the globe and anchoring at the medial and lateral canthi. There are three portions of the muscle: the pretarsal portion which covers the tarsal plate, the palpebral part which covers the eyelid, and the orbital part which overlies the bony elements. The orbital portion is responsible for the sphincteric action of the muscle, and the palpebral portion is involved in the blink reflex. In the midface, the facial mimetic muscles are deeper and the facial fat compartments limit surface identification of individual muscles. The nasal muscles are the only group of muscles that have clear surface anatomy similar to the forehead. Just below the glabellar complex is the nasalis muscle, with the upper part traveling transversely across the dorsum and vertically down the lateral sides of the nose. Contraction of the transverse head compresses the dorsum, the vertical heads dilate the nares. These muscles will form the “bunny lines” or oblique rhytids of the nasal dorsum. The depressor septi muscle is a muscle that originates in the columella and inserts into the upper lip which will rotate the nasal tip downward and elevate the upper lip. The elevators of the upper lip are involved in speaking, eating, and the facial expressions of the upper lip. The zygomaticus major inserts at zygomatic body just below the lateral orbital rim and extends medial and inferior to insert into the lateral aspect of the upper lip. The zygomaticus minor is just medial to the zygomaticus major and both act to draw the lateral lip up and back. The principal elevator is the levator labii superioris which originates in the mid‐orbit medial to the zygomaticus minor and acts in concert with the levator labii superioris alequea nasi, which originates from the lateral nose. The levator anguli oris (LAO) is a deep muscle originating in the area of the canine fossa and inserts near the commissure to elevate the corner of the mouth. The risorius muscle arises from the lateral cheek and is variably developed and pulls the commissure laterally. The orbicularis oris muscle is the sphincteric muscle of the mouth and consists of superficial and deep parts. The deep layers act as a constrictor and the superficial can bring the lips together and provide expression. The lower lip depressors act to balance and oppose the elevators of the upper lip. The depressor anguli oris (DAO) arises laterally and inserts into the modiolus along with the orbicularis oris, risorius, and LAC. The DAO serves to depress the commissure and can be seen via surface anatomy as the melomental fold (marionette line). The depressor labii inferioris is medial to, and covered by some DAO fibers on its lateral surface. The depressor labii inferioris passes upward and medial to insert into the skin, mucosa, and orbicularis fibers to depress and evert the lower lip. The mentalis muscle is a paired midline muscle deep to the other depressors and its action serves to elevate and protrude the lower lip. The platysma originates in the neck as a paired muscle that crosses the mandibular border and inserts into the dermis and subcutaneous tissues of the lower lip and chin. It has been demonstrated that the mimetic muscles of the face are arranged in four layers [8] (Figure 1.4).

Facial Anatomy and Patient Evaluation

1.1 Facial Anatomy

1.2 Anatomy of Facial Skin

1.3 Anatomy of the Superficial Fat Compartments

1.4 Anatomy of the Facial Fasciae

1.5 Anatomy of the Facial Mimetic Muscles

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree