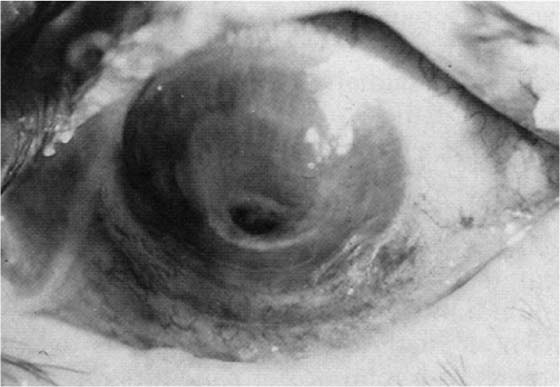

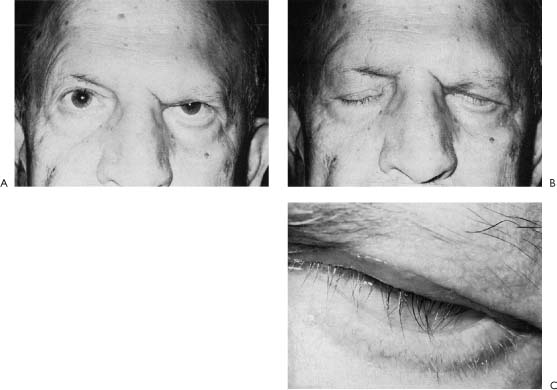

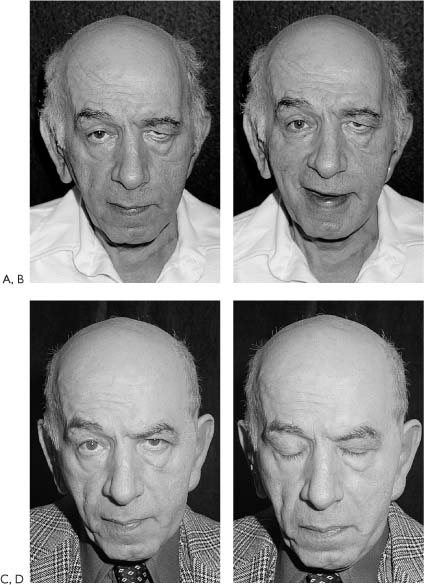

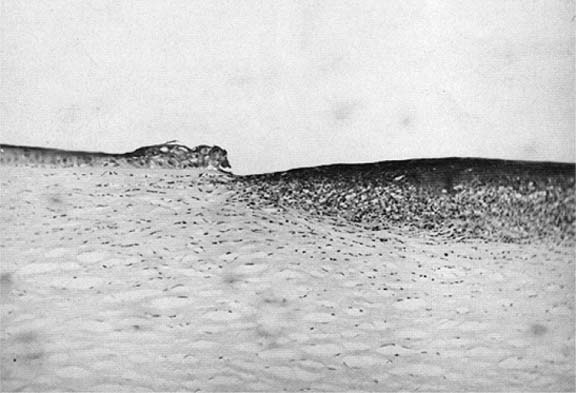

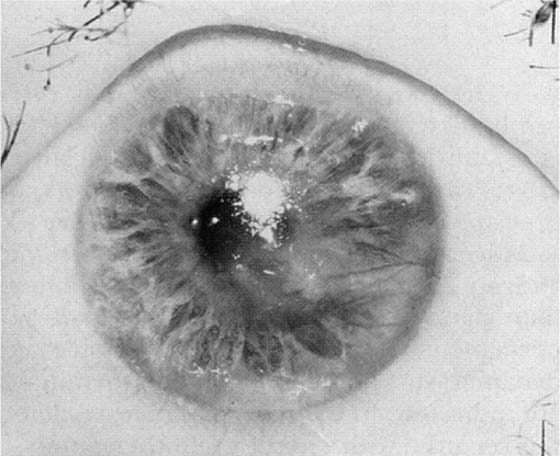

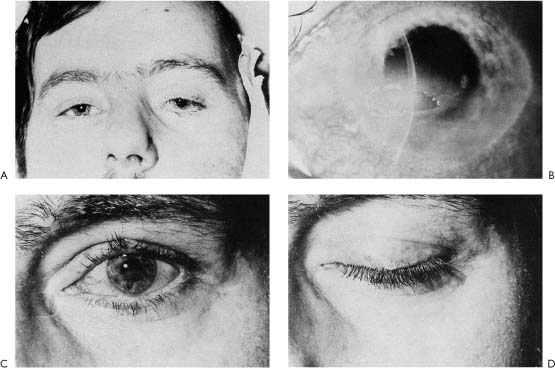

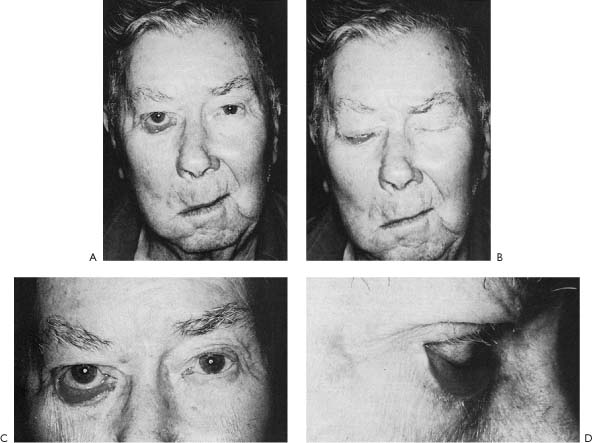

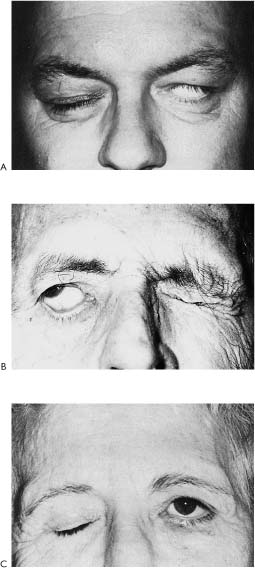

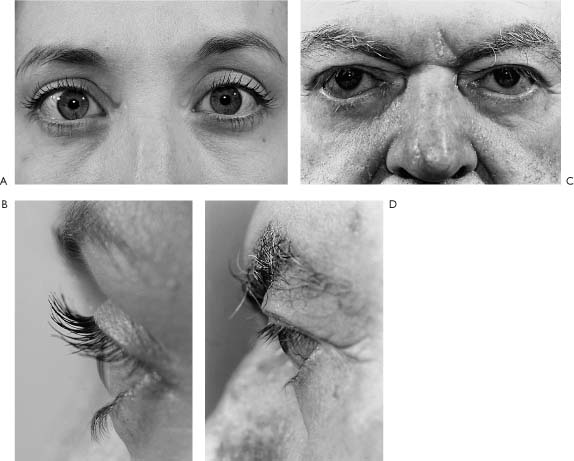

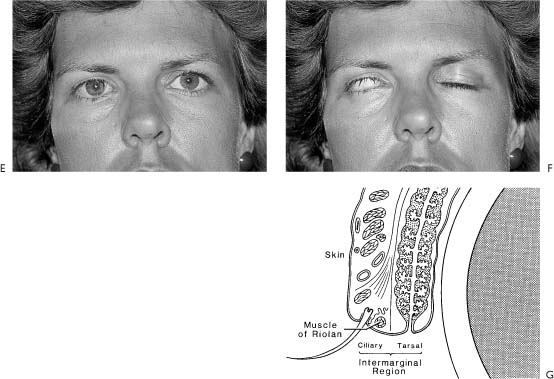

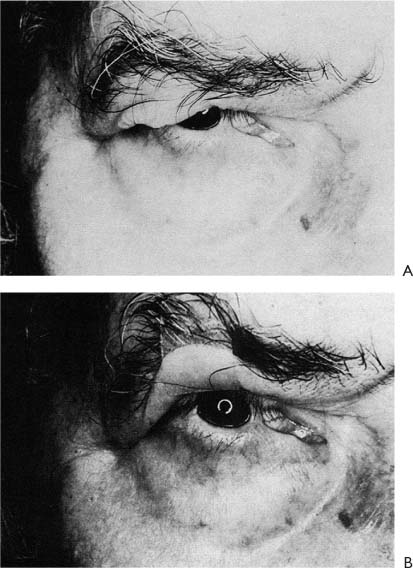

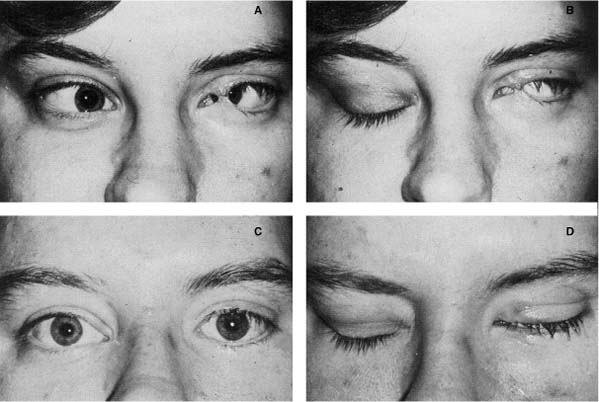

6 “Guard them like the pupil of an eye”* Figure 6-1. Right, cornea with exposure keratitis resulting in ulceration. Normal cornea is seen at left. Note loss of epithelium and Bowman membrane and marked inflammatory reaction in stoma at right (H&E, X65). (From Levine RE.1 With permission) Patients with facial paralysis may have eye problems ranging from slight ocular irritation to corneal ulceration, perforation, and blindness (Figs. 6-1 through 6-4).1 The severity of these complications is related to the degree and duration of the paralysis. The major factors leading to these problems include incomplete eyelid closure (referred to as lagophthalmos; Fig. 6-5), paralytic ectropion of the lower lid (Fig. 6-6), loss of corneal sensation, decreased tear production, and absence of reflex rolling up and out of the cornea with efforts to close the eyelids (known as Bell’s phenomenon; Fig. 6-7). In this chapter, a systematic approach to the evaluation and medical management of these factors will be stressed. Surgical techniques to reanimate the eyelids should only be considered for those patients in whom medical management fails or for patients with total or permanent paralysis in whom lasting corneal protection and correction of malpositioned eyelids is necessary. Figure 6-2. Recurrent neurotrophic ulceration with marked vascular ingrowth. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.) Figure 6-3. Patient with marked fifth and seventh cranial nerve impairment following resection of a large acoustic schwannoma. Eight months later, severe neurotrophic and exposure keratitis progressed to corneal perforation, and keratoplasty was required. The cause, duration, and severity of the patient’s ophthalmologic problem must be determined. This is done by taking a careful patient history and performing a thorough physical examination. History Prior to planning treatment, every effort must be made to find the cause of the facial paralysis. Once this is established, the duration of the facial paralysis can be predicted, and the severity appreciated. For example, if the facial nerve was sacrificed during surgery to resect a tumor and no effort was made to graft the nerve, paralysis will very likely be total and permanent. In such a case, aggressive and dynamic surgical rehabilitative techniques are indicated. In contrast, if the nerve defect was repaired with a nerve graft, paralysis would be total postoperatively, but recovery might be expected in 6 months to 1 year, and for such patients, medical management might be more appropriate. Finally, if the patient had acute Bell’s palsy and facial nerve involvement was incomplete, the prognosis would be quite favorable for complete recovery within 6 weeks to 3 months, and the most conservative form of treatment would be indicated. Figure 6-4. Results of eye reanimation using eye spring. A, Patient post-acoustic tumor surgery showing the BAD syndrome: loss of Bell’s phenomenon, Anesthetic cornea, and a Dry eye. B, Within 10 days of acoustic surgery, a corneal ulcer developed. C, With appropriate ophthalmologic care, the ulcer healed, and the eyelid was reanimated with a spring implant. In this photograph, the spring is in place with the eyelids opened. D, Eyelid closure achieved with the eye spring. Figure 6-5. Facial paralysis on the left side. A, Note marked brow droop, lagophthalmos, lower lid droop, and entropion of the upper eyelid. B, On attempted lid closure, brow droop tends to push upper lid shut. C, Close-up view of upper lid entropion resulting in lashes rubbing on the globe. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.) Once the cause of the paralysis has been ascertained, the patient should be questioned about ocular problems since the onset of the facial paralysis. These may include redness, irritation, dryness, photophobia, or blurred vision. A history of ocular problems unrelated to the facial paralysis may affect management of the presenting condition. For example, bilateral refractive errors may be aggravated by poor tearing or using ointment in an eye affected by facial palsy. In addition, treatment may be affected by preexisting monocular vision, chronic lid infection, or ptosis; if the eye with the best visual acuity is the one on the side of the facial paralysis, extreme caution must be taken to protect this eye and preserve vision. Finally, the physician should elicit any history of prior corneal ulceration or ophthalmologic surgery, and should find out what previous attempts may have been made to treat the paralyzed eyelids. Physical Examination The physical examination of the patient with facial paralysis includes evaluation of visual acuity and visual fields; the level of the eyebrows; eyelid approximation with involuntary blink and voluntary effort; extraocular muscle function; pupil size, symmetry, and response to light; and funduscopy. The conjunctiva and cornea are examined for inflammatory changes, and fluorescein is applied to the surface of the globe to identify areas of early epithelial damage or loss. Ideally a slit-lamp examination should be done to determine the degree of any corneal involvement (Figs. 6-2 through 6-4). The presence of the BAD syndrome calls for aggressive medical therapy since eye complications almost always occur in patients with this syndrome (Fig. 6-4). The BAD syndrome consists of lack of Bell’s phenomenon, which may lead to poor corneal coverage and lack of tear distribution; corneal anesthesia, due to exposure or fifth nerve deficit, as may occur in resection of a large posterior fossa tumor; and dryness, due to loss of tear production, as with lesions at or proximal to the geniculate ganglion. Visual Acuity Perhaps the most important part of the examination is to determine visual acuity because this is a sensitive indicator of corneal change. Each eye is tested separately by having the patient read letters from a standard Snellen distance chart or a card of the Rosenbaum or Jaeger type (Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener, Cooper Vision Pharmaceuticals Inc., San German, Puerto Rico). Eyebrow Brow ptosis can be evaluated by noting the level of the brow on the involved side compared to that on the normal side at rest and with elevation (with wrinkling the forehead). In addition, paralysis of the frontal muscle may cause severe impairment in upward gaze as a result of severe brow ptosis (Fig. 6-5). Figure 6-6. A, Complete facial paralysis 1 week following Bell’s palsy. Note severe sagging of the involved side on the right. B, Significant lagophthalmos due to ectropion. C,D, Severe ectropion and conjunctival reaction. Eyelids The upper eyelid is examined for its ability to cover the cornea with efforts to blink involuntarily and with voluntary eyelid closure. The patient with a partial facial palsy may be able to approximate the eyelids with a voluntary effort, but the cornea is left exposed with reflex blinking because of incomplete eyelid closure and absence of the Bell’s phenomenon (Fig. 6-7). In addition, the presence of lagophthalmos or lack of upper and lower eyelid approximation should be noted. Eyelid approximation is primarily a function of the upper eyelid since its downward movement is 5 to 7 mm compared to the lower lid, which only elevates 0.5 mm. However, although lack of lower lid elevation may not play a significant role in lagophthalmos, the presence of paralytic ectropion leads to punctal eversion and may be responsible for excessive epiphora, corneal drying, and lower conjunctival inflammation and scar retraction (Figs. 6-6 and 6-7B). Lid Lash Droop Sign Lid lash droop has been recognized by the senior author (MM) as one of a constellation of physical sequelae of complete facial paralysis. To our knowledge, however, this phenomenon has not been reported previously. In addition to drooping, the lashes grow in an irregular disrupted fashion, tend to collect mucus, and become matted. The drooping lashes of the upper lid may contact the cornea causing irritation and abrasion (Fig. 6-8). Whitnall2 suggests that the ciliary bundle of the orbicularis oculi muscle exerts pressure on the lash follicles and it is this pressure that is responsible for determining the angle at which the lash curves away from the globe. It is likely that the eyelash droop is caused by loss of resting tone in this muscle group as the result of facial paralysis.3 This is an important sign for two reasons: (1) it is associated with long-standing complete denervation of the facial nerve and suggests a poor prognosis for spontaneous recovery, and (2) the drooping lashes may prolapse against the cornea causing irritation and possible abrasion calls for corrective measures. Conservative treatment requires keeping the eyelashes clean. We suggest that patients clean the eyelashes with a dilute solution of baby shampoo (1 part baby shampoo to 1 part water). A cotton tip applicator dipped into the solution is used to gently swab the lashes from the roots to the tips at least twice a day. An eyelash curler is of limited value, offering relief for a very short time. When this condition becomes symptomatic and does not respond to conservative measures, a surgical procedure to evert the eyelashes is effective and will be discussed in the section on surgical management. Figure 6-7. Bell’s phenomenon. A, Patient with good Bell’s phenomenon protecting the cornea despite very poor lid closure. B, Incomplete Bell’s phenomenon demonstrating normal oculogyric reflex with globe rotating up and out in an effort to protect the cornea. C, Absence of Bell’s phenomenon with complete exposure of cornea with voluntary efforts to close the eyelids. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.) Conjunctiva The conjunctiva is inspected for injection, irritation, or infection. Cornea Corneal clouding, scarring, and neovascularization can be determined by oblique illumination with a bright light (Figs. 6-2 through 6-4). Corneal sensation is tested with a wisp of sterile cotton applied to the cornea, or at the time that tear production is tested with Schirmer paper. When the cotton or paper is placed over the cornea, the patient should be asked if the feeling is equal or decreased in the involved side compared to the normal side. When corneal anesthesia is present and tear production is absent, the ophthalmologist should be consulted, as the combination of anesthesia and lack of tearing almost always leads to severe ocular complications. Patients with corneal anesthesia experience little or no discomfort from even a severely traumatized or desiccated corneal epithelium and have decreased ability to maintain or heal their corneas because of lost “neurotrophic” factors. Next the cornea should be evaluated by application of fluorescein dye, which will help to define any area of corneal dullness or opacity. Ideally a slit lamp should be used to define the depth of corneal involvement, but a pen light with a cobalt blue filter (Smith, Klein and French) works quite well. By examining the cornea with a magnifying loupe or binocular operating microscope and the cobalt blue filter light, areas of corneal erosion or ulceration may be identified as green fluorescent areas with a blue background. When such areas are present, ophthalmologic consultation is imperative because the integrity of the eye is in jeopardy. Tearing Evaluation of tear production by Schirmer’s tear test (Smith Miller and Patch Division, Cooper Laboratories Inc., Wayne, New Jersey) is one of the most important aspects of the ocular evaluation, as lack of tearing is a common finding in patients with lagophthalmos or incomplete eyelid closure associated with facial paralysis, and usually is accompanied by loss of interpalpebral corneal punctate epithelium. Such loss is manifested by a red line of hyperemic conjunctival vessels running from the medial to the lateral canthus that stains positively with fluorescein dye. Pupils The pupils are examined for size, symmetry, and response to light. A miotic or small pupil is a sign of corneal irritation, while an irregular small pupil may be due to severe anterior chamber inflammation with synechiae formation. Unless there has been significant corneal involvement, such inflammation suggests a cause (e.g., sarcoid) other than Bell’s palsy. Figure 6-8. Lid lash droop sign. A,B, Normal appearance of eyelashes. C,D, Lash droop associated with aging causing senile laxity. E,F, Lash droop associated with long-standing total facial paralysis. Nine years following resection of facial nerve schwannoma. Note lashes not only droop, but they lose their parallel orientation and have an irregular matted appearance. G, Diagram of location of muscle of Riolan. According to Whitnall,2 the ciliary bundle of the orbicularis muscle exerts pressure on the lash follicles and is responsible for maintaining the normal lash curvature away from the globe. In cases of long-term, complete denervation, it is conceivable that atrophy and fibrosis of this muscle band is responsible for the drooping and disorganized appearance of the lashes as noted in E and F. Extraocular Muscles Evaluation of extraocular movements may detect lack of ability to rotate the eye on the involved side to the lateral position, indicating sixth cranial nerve involvement. When facial paralysis is accompanied by a sixth cranial nerve deficit, another disease process may be present. One of the most common disorders associated with this combination is diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic patients may present with facial paralysis and a third cranial nerve palsy resulting in diplopia and upper eyelid ptosis. In such cases, it is critical to evaluate not only extraocular movement but also the response of the pupil to light, as diabetic neuropathy can be distinguished from a retrobulbar compressive lesion by the preservation of pupillary response to light in the former. Small vessel disease associated with diabetic neuropathy spares the fibers that run with the third cranial nerve to innervate the pupil. Nystagmus The presence of nystagmus is another finding that indicates a disorder other than Bell’s palsy. Vertical or rotary nystagmus suggests that a central deficit is present. Alternating nystagmus in lateral gaze is diagnostic of a lesion involving the medial longitudinal fasciculus and is most commonly associated with a demyelinating disorder such as multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmoscopic Examination Ophthalmoscopic examination evaluates the cornea, anterior chamber, lens, posterior chamber, and fundus. A survey of these structures can detect corneal changes, anterior chamber inflammatory processes, a dense cataract responsible for impaired vision, or funduscopic evidence of systemic disease such as diabetes, which may be contributing to the paralysis. In addition, papilledema, possibly indicating the presence of a life-threatening intracranial lesion, may be detected in this way. Tonometry Tonometry may be useful in detecting pathology unrelated to the facial paralysis such as glaucoma but important in the management of the eye on the paralyzed side. However, tonometry must be performed with extra caution when the cornea is vulnerable to injury due to exposure and dryness, and the examiner should be aware that the tension in the eye on the paretic side is usually 2 to 3 mm lower than that on the normal side, possibly as the result of lack of orbicularis oculi muscle tone.4 Another observation worthy of note is the change in intraocular tension in patients with cerebellopontine angle tumors: on occasion tension on the affected side has been found to be 5 to 7 mm lower than that on the normal side. The reason for this is not known. A number of factors favor medical rather than surgical management of paralyzed eyelids, and these are listed in Table 6-1. In general, medical treatment of these ophthalmologic problems is directed at humidification of the eye, which may be accomplished by use of eye drops and ointments, artificial methods of closing the eye, protective devices, or maintenance of the eye’s natural moisture. Each of these will now be discussed in detail. Eye Drops and Ointment The simplest way to protect the cornea and keep it moist is with artificial tears and ointments. The numerous preparations on the market differ in their major ingredients, viscosity, and preservatives (Table 6-2), and it is useful to be aware of the variety of preparations because patient tolerance of each is variable. If one preparation is not suitable because of irritation, then another can be chosen. The products vary primarily by their major ingredient, which may be polyvinyl alcohol, methylcellulose, or hypotonic salt solution. Lubricant additives include mineral oil, petrolatum, or boric acid.

Eye Reanimation Techniques

Mark May, M.D., Robert E. Levine, M.D., Bhupendra C.K. Patel, M.D., and Richard L. Anderson, M.D.

Abnormalities of eyelid position and defective tearing are the two major causes of eye symptoms associated with paralysis. This chapter will deal with the medical and surgical management of these problems. In addition, this portion of the book will cover treatment of excessive as well as deficient tearing. For the sake of comprehensiveness, aberrant tearing (crocodile syndrome) and sweating (Frey’s syndrome) will be included as the mechanisms for both involve faulty regeneration of the parasympathetic system following facial nerve injury. However, abnormalities in lid position due to hyperkinetic disorders causing an inability to open the eyelids such as blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm and synkinesis following faulty regeneration will not be covered because they are included in Chapters 23 through 27.

Evaluation and Medical Considerations

Ophthalmologic Evaluation

Medical Management

|

There are some guidelines that will help to select the preparation that will be most effective in a given patient.

| Trade Name | Ingredients |

| Artificial Tears | |

| Long-acting, high viscosity | |

| Celluvisc | Carboxymethylcellulose 1%* |

| Murocel | Methylcellulose 1% |

| Visculose 1% | Methylcellulose 1% |

| Long-acting, medium viscosity | |

| Adsorbotear | Hydroxyethylcellulose, povidone 1.67% with water soluble polymers |

| Cellufresh | Carboxymethylcellulose 0.5% |

| Medium duration, medium viscosity | |

| Isopto Tears | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.5% |

| Lacril | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.5%, gelatin A 0.01% |

| Liquifim Forte | Polyvinyl alcohol 3% |

| Lubrifair Solution | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, Dextran 70 |

| Lytears | Cellulose derivative |

| Moisture Drops | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.5%, Dextran 30 |

| Tearisol | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.5%, boric acid |

| Tears Naturale II | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.3% in water-soluble polymeric system |

| Tears Naturale Free | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 0.3% in water-soluble polymeric system* |

| Visculose 0.5% | Methylcellulose 0.5% |

| Short duration, low viscosity | |

| AKWA Tears Solution | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| Hypotears | Polyvinyl alcohol 1% in Lipiden polymer |

| Hypotears PF | Polyvinyl alcohol 1% in Lipiden polymer* |

| Liquifilm | Polyvinyl alcohol 1.4% |

| Methulose | Methylcellulose 0.25% |

| Ocu-Tears | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| Refresh | Polyvinyl alcohol 1.4%, povidone 0.6%* |

| Tearfair Solution | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| Tears Plus | Polyvinyl alcohol 1.4%, povidone 0.6% |

| Ocular Lubricants (Ointments) | |

| AKWA Tears Ointment | White petroleum, mineral oil* |

| Duolube | White petroleum, mineral oil* |

| Duratears Naturale | White petroleum anhydrous liquid lanolin* |

| Lypotears Ointment | White petroleum, light mineral oil* |

| Lacri-lube NP | White petroleum, mineral oil* |

| Lacri-lub SOP | White petroleum, mineral oil |

| Lubrifair | White petroleum, mineral oil, liquid lanolin |

| Ocu-Lube | White petroleum |

| Petrolatum | White petroleum |

| Refresh PM | White petroleum, mineral oil, lanolin* |

| Tearfair | White petroleum, mineral oil, lanolin, derivatives |

| Slow-release Lubricants (Inserts) | |

| Lacrisert | Hydroxypropyl cellulose |

(* indicates preservative-free preparation)

Artificial Eye Closure

Tape Tape may be used to keep the eyes open for vision (Fig. 6-9) or to keep the eyelids closed to protect the cornea. In particular, if there is significant incomplete eyelid closure (lagophthalmos), the eyelids may need to be taped shut to protect the cornea during the night. However, when an ointment is to be used prior to taping the eyelids shut, care must be taken to keep the skin surface free of medication or the tape will not adhere.

Transpore tape (1-in width, 3M Co.) has been found to work quite well for taping the eyelids closed. The patient should be supervised during eyelid taping to ensure that the eye is closed properly so that the tape does not rub against the globe: patients with hypesthetic or anesthetic corneas may not be able to determine when the lids have been closed adequately. If supervision is impossible, the patient should be told to ensure that no light can be detected by the affected eye after the lids have been taped.

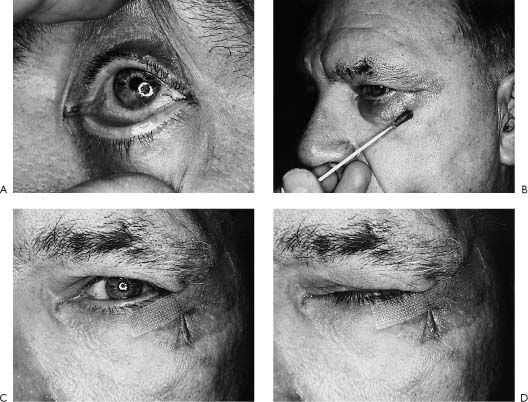

To support a drooping lower lid, the end of the tape should be applied to the center of the lower lid with the upper edge about 1/8 in below the lashes. The tape should then be pulled up laterally and secured to the lateral orbital rim (Figs. 6-10 and 6-11).

Figure 6-9. Patient 3 months following resection of an acoustic schwannoma and sacrifice of the facial nerve on the right side. A, Severe paralytic brow droop with limitation of upward and lateral gaze; a tarsorrhaphy web is also present. B, The upper lid and brow are held in an upward position with tape in an effort to improve vision.

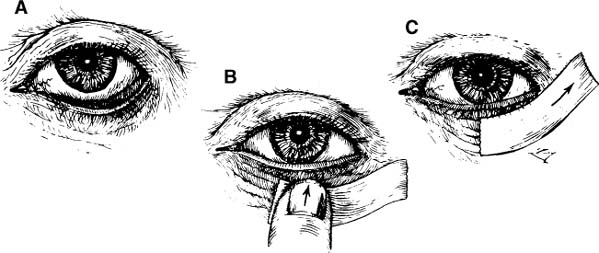

Figure 6-10. Technique of supporting lower lid with tape. A, Drooping lower lid. B, Tape is applied to center of lower lid. C, Tape is secured with tension directed up and laterally. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

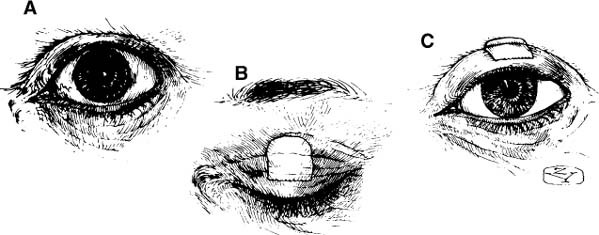

Trial and error will demonstrate the best way of eliminating lid droop in a given patient. Normalization of lower lid position will bring the reservoir of tears into contact with the cornea and will decrease the palpebral aperture, thus limiting abnormal evaporation of tears and reducing irritation of the palpebral conjunctiva caused by ectropion. The palpebral aperture can be further narrowed by limiting opening of the upper lid. This can be accomplished easily by placing a small crescent of tape over the tarsal-supratarsal fold in the upper lid (Figs. 6-12 and 6-13) to act as a splint to limit excessive opening of the lid. On the other hand, in some cases an eyelid crutch may be placed in the tarsal-supratarsal fold (Fig. 6-14) to keep the eyelids open for vision.

Figure 6-11. Patient with Bell’s palsy and BAD syndrome (inadequate Bell’s phenomena, anesthesia of cornea, and dry eye) with exposure keratitis. A, Corneal stain with fluorescein. B, Application of tincture of benzoin. C, Lower lid splinted with Transpore tape (manufactured by 3M). D, Enhanced eye closure.

Pressure Patch A pressure patch is another device that may be used to effect lid closure temporarily. It is difficult to ensure eyelid closure with a simple eye patch, but a pressure patch, consisting of two eye pads skillfully placed, is generally effective. However, if the cornea is anesthetic and the eyelids remain slightly open, the eye pad can abrade the cornea. This can be prevented by taping the eyelids shut first and then reinforcing the closure with the pressure patch.

Figure 6-12. Technique for improving upper lid position with tape. A, Note widened palpebral aperture due to orbicularis weakness. B, Crescent piece of tape is placed to override lid fold. C, Note how tape splints upper lid and helps to normalize palpebral aperture. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

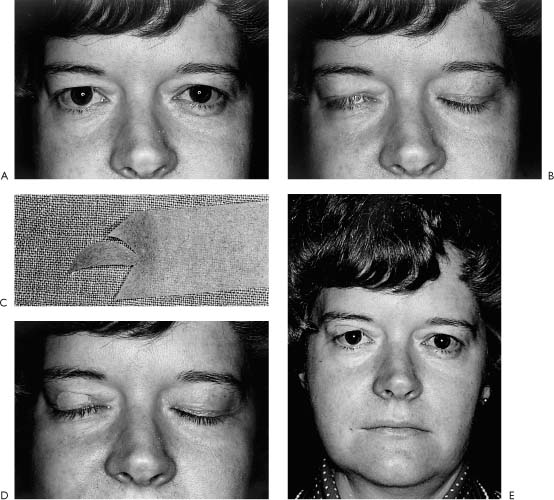

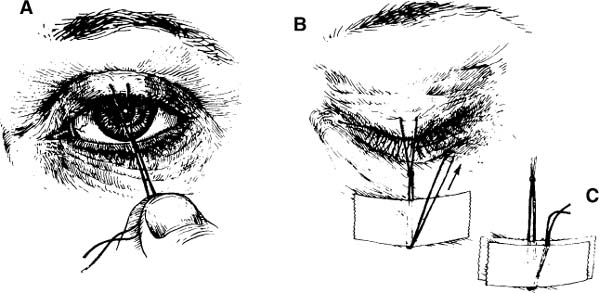

Lid Sutures When the eyelids are difficult to tape shut, placing lid sutures may be preferable. However, this technique is reserved for those patients who do not respond to the other medical methods, and is the last resort before considering surgical techniques. A simple and effective means of lid closure is to place a 5-0 nonresorbable suture through the skin of the upper eyelid and then to tape it to the cheek (Fig. 6-15). Such a suture should be used whenever temporary lid closure is indicated and taping is inadequate to keep the lids shut. The eyelids may still be opened easily to check pupillary reflexes and corneal integrity as often as necessary, and should the surgeon choose to leave the lids open at intervals, the ends of the suture may be taped loosely to the forehead. Generally, such a suture can be left in place for 4 to 6 weeks; thereafter, it tends to extrude. The lid suture is a satisfactory technique for managing difficult cases and ensures that the paretic lids will remain firmly closed beneath a pressure dressing. This technique is useful in patients with deeply recessed eyes, or in patients with strong lid retraction due to an overactive levator superiorus.

Figure 6-13. Technique of improving upper lid position with tape. A, Note widened right palpebral fissure owing to orbicularis weakness. B, Incomplete eyelid closure. C, Crescent of tape is cut. D, Tape placed to override lid fold and to assist lid closure. E, Appearance with eyes opened.

When a lid suture is being secured, the patient should be instructed to attempt to close both eyes. Enough tension should be exerted on the suture to pull the lid shut slightly more than is normal, then the suture should be taped in place and the patient asked to open the eye. If the lids can be opened even slightly, the suture should be retaped under increased tension. To prevent loosening of the suture, its free ends should be brought up over the edge of the tape and secured with a second piece of tape placed over the first. A small amount of antimicrobial ointment placed at the entry and exit sites of the suture three or four times daily helps to prevent infection.

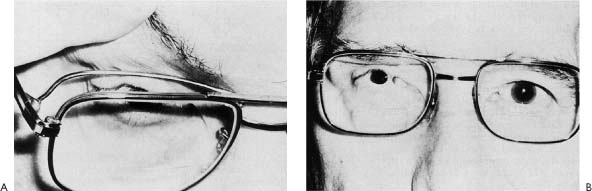

Figure 6-14. Same patient as depicted in Figure 6-9. An effort was made to correct the defect with an eyebrow crutch. A, Note crutch, attached to eyeglass frames, fits in the region of the tarsal-supratarsal fold. B, Patient wearing eyeglasses to show how the eyelid crutch holds the upper lid away from the upper lid margin.

Figure 6-15. Technique of placing lid suture. A, Nonresorbable suture is placed through upper lid skin, tied, and pulled downward to close the lid. B, Suture is taped to cheek. C, Second piece of tape is placed to keep suture from slipping. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

Figure 6-16. Technique of suturing eyelids together. A, Suture has been sewn through both lids. B, Suture is tied in a bow to permit opening and reclosure of the lids. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

A second type of lid suture is useful in situations in which the lids are to be kept closed for several days or more (Fig. 6-16). Each arm of a 4–0 nonresorbable suture is sewn over a cotton pledget to enter the skin of the upper lid several millimeters above the lashes and to emerge at the grey line.

The suture then enters the grey line of the lower lid and exits through the skin several millimeters below the lashes. The globe should be protected during the passage of these sutures. The ends of the sutures are then tied over a cotton pledget. The first knot is a surgeon’s tie, and the second is a bow, with the ends left long. Tying the knot in this manner permits the lids to be opened to inspect the globe at intervals and then to be reclosed.

Botulinum A Toxin Botulinum toxin injection into the supratarsal fold area is an effective alternative treatment for patients with exposure keratitis who do not respond to the approaches mentioned and offers a medical option with a temporary effect for a condition that has a favorable prognosis for spontaneous recovery. Botulinum injection into the levator palpebrae superioris to induce ptosis has been reported for treating exposure corneal ulceration.5,6 Ninety percent of the ulcers completely healed with this technique. The cornea was covered completely by the lid in all but one case. Complete ptosis was produced in 75% of the cases in an average of 3 days, and lasted for 16 days before recovery began. Superior rectus muscle paresis was seen in 68% of patients, but recovered in all cases in an average of 6 weeks. Botulinum has also been used to treat corneal problems from Grave’s ophthalmopathy.7

Smet-Dieleman et al.7 reported use of botulinum toxin in patients with facial palsy for treatment of incomplete eyelid closure. Initially, patients with severe corneal problems were treated; later, botulinum toxin was used for partial relaxation of the levator muscle in cases of incomplete eyelid closure even without major corneal problems.

In our experience 10 units of botulinum injected into the supratarsal fold was effective to create ptosis without any extraocular muscle deficit. This pharmacologic “tarsorrhaphy” was noted the day following the injection and was effective for 6 weeks (Fig. 6-17). Although the use of botulinum toxin seems attractive, disadvantages include restriction. of vision due to upper lid ptosis, possible paresis of the superior oblique muscle, and delay in onset of up to 3 days for full effect. Patel and Anderson8 have abandoned using botulinum toxin in patients with an acute seventh nerve palsy as vertical diplopia persisted in one patient for 9 months after injection before it cleared.

Figure 6-17. Botulinum toxin “chemical” tarsorrhaphy. Patient with Bell’s palsy. There is severe lagophthalmos with absence of Bell’s phenomenon. A, The affected eyelid stays open in spite of volitional effort to squeeze the eyelids tightly shut. The patient suffered from exposure keratitis in spite of medical efforts. A gold weight insert extruded. A spring implant also extruded. B, A “chemical” tarsorrhaphy was achieved with 5 units of botulinum toxin injected into the tarsal-supratarsal crease. C, Three days postinjection with eyes open. D, Six months later, recovery of facial function with synkinesis is noted. The effect of the botulinum lasted 3 months, about the time facial recovery was sufficient to provide eye coverage. E, Eyes opened. F, Eyes closed demonstrating the “chemical” tarsorrhaphy was effective during the critical 3 months. Now there is full recovery from the effects of the toxin.

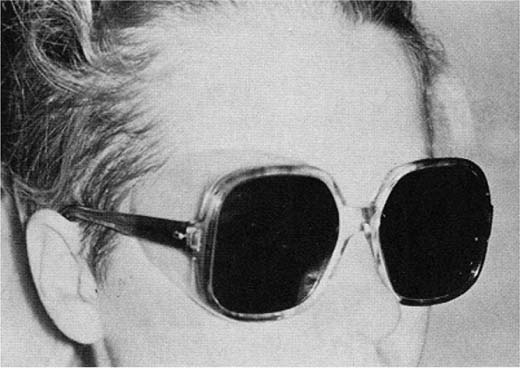

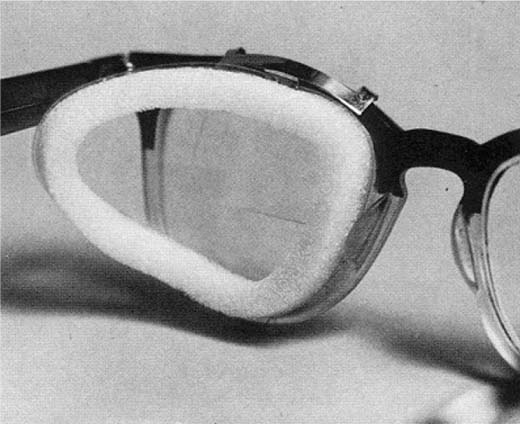

Protective Devices Protective lenses, wraparound sun glasses, or goggles (Fig. 6-18) may be used to decrease evaporation from the eye. In addition, a simple and inexpensive moisture chamber is available that can be attached to ordinary spectacles (Fig. 6-19) or secured with an elastic band around the head (Pro-Optics, 371 Wood Work Lane, Palatine, Illinois 60067).

Soft Lenses Soft lenses have also proved to be useful in selected patients to protect a neurotrophic cornea. Unfortunately it is difficult to keep soft lenses in place in patients who have marked lower lid droop or marked impairment of lid closure. Further, soft lenses require a moist eye in order to remain pliable and maintain their position on the eye. Thus, use of soft lens does not eliminate the need to keep the eye moist, so they have limited value in managing the patient with paralyzed eyelids.

Figure 6-18. A plastic moisture chamber has been fabricated on a pair of ordinary sunglasses to provide extra protection for the involved eye.

Figure 6-19. Moisture chamber which can be slipped on ordinary spectacles to form one-sided goggle. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

Scleral Shells Although scleral shells have been useful in some cases,9 in Levine’s experience, patients frequently found them to be bothersome and uncomfortable. Despite the availability of expert technical assistance in fitting the shell, the period of adjustment to the shell and the multiple fittings needed to achieve good vision may require months. Further, when the patient has reduced corneal sensitivity, there is a real hazard of corneal damage from the shell.

Maintaining Humidification (Table 6-3)

Room Humidifiers Evaporation of tears is acclerated by low humidity. Thus using a room humidifier to maintain high room humidity may be of significant benefit to patients who spend many of their waking hours in a single room.

|

| If you have any questions about the eye becoming reddened, or uncomfortable, or about a change in vision, you are to call for further instructions. |

(From Smith MFW, McElveen J: Neurological Surgery of the Ear: Eye Protection in the Paralyzed Face. St. Louis, Mosby-Year Book Inc., 1992, pp 127–130. With permission.)

Voluntary Blinking In addition, patients can help to keep the eye moist by periodically and intentionally closing the eyelids, either by muscular action if possible or by using the back of the thumb to pull the upper eyelid down over the cornea. By this action, the tears are distributed across the front surface of the eye. Because even patients with facial paralysis who have good lid closure may have impaired involuntary blinking, they should be encouraged to voluntarily blink as often as necessary and at least six times per minute to keep the eye moist. Patients with poor upper eyelid closure but good Bell’s phenomenon should also blink voluntarily by rolling the eye up so that the edge of the upper lid distributes the tears.

Ophthalmologic Re-Evaluation

Patients should be re-evaluated every few days if there is evidence of the BAD syndrome, and more often in the presence of early corneal changes. In the event that there is evidence of progression of corneal deterioration, the cornea must be protected by some method of eyelid closure, and if medical means fail to adequately protect the cornea from breakdown, surgical methods must be considered. However, patients who seem to be free of eye problems must also be examined frequently to avoid the development of such sequelae.

When a patient who had previously been free of eye problems later presents with an inflamed eye, the patient should be completely re-evaluated. The nature and extent of the current problem must be determined, and its relation to the facial paralysis is evaluated. It is possible, for instance, that uveitis or even glaucoma may develop independent of the facial paralysis, but ocular inflammation developing in association with facial paralysis may also signal the presence of sarcoidosis or a disseminated neoplastic process.

The delayed onset of eye inflammation may be due to progressive loss of facial muscle tone, possibly resulting in increased lagophthalmos or progressive paralytic ectropion. Another reason why such problems may occur later in the course of the disorder is relaxation of compliance with the recommended medical treatment. Frequently, the patient may become lax in use of prescribed medications, or may be exposing the eye to environmental irritants. Has the patient returned to work in an air-conditioned office? Is the patient swimming without wearing goggles or allowing the affected eye to be exposed daily to the wind while waiting for the bus? Only by performing a complete re-evaluation of the patient can the significance of these factors be determined and the treatment plan modified appropriately.

However, regardless of the cause of the late onset of eye problems, they must be treated. Generally, keeping the eyelids shut until the cornea has recovered is the treatment of choice, and if this cannot be accomplished by means of tape alone or a lid suture, then a surgical approach should be considered.

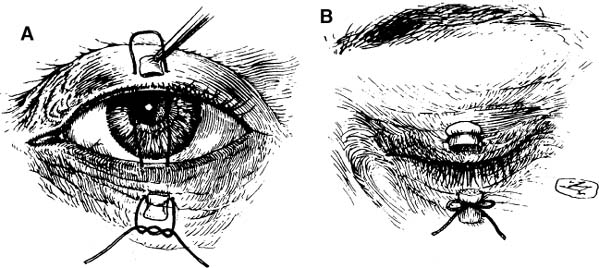

Brow, Upper Lid, and Lower Lid

Surgical Management When medical methods fail, surgical measures must be considered. Ideally, lid reanimation surgery should be performed before corneal damage occurs. Based on a thorough review of the history of oculoplastic surgery (1896–1996), Patel and Anderson8 state that “partial tarsorrhaphy,” first described by von Walther in 1826, remained the mainstay of eyelid rehabilitation in facial palsy for nearly 150 years. The tarsorrhaphy still remains the “gold” standard among practicing general ophthalmologists. This is in spite of its limitations: the procedure restricts vision, produces a grotesque appearance, and in some cases, does not even protect the cornea from exposure and subsequent breakdown. Further, if the patient’s facial palsy recovers, reversal of the tarsorrhaphy may cause entropion, trichiasis, eyelid margin notching, and formation of epithelial cysts. The main purpose of this section is to emphasize that methods available to reanimate the eye region should displace the tarsorrhaphy and relegate it to a procedure that is used as a last resort (Figs. 6-20 through 6-22).

Figure 6-20. A 72-year-old patient presented with multiple tarsorrhaphies performed following her acoustic tumor surgery. Note that although the eye is nearly sewn shut, the cornea is still not well protected, even with attempted lid closure. Corneal ulceration and scarring have been noted in such cases in spite of tarsorrhaphy. Therefore, periodic corneal evaluation must be continued even after performance of a tarsorrhaphy.

Figure 6-21. Note stretching of tarsorrhaphy bar that forms an unsightly adhesion band. This tarsorrhaphy attempt failed to protect the cornea, limited vision, presented a cosmetic blight, and deformed the lash line disrupting the lashes (see Figs. 6-22 and 41).

General Indications for Surgery A number of factors make it difficult to manage the problems associated with paralyzed eyelids by medical means alone. Patients who lack one or more of the factors listed in Table 6-1 should be managed surgically as soon as it becomes apparent that medical management is ineffective. A prime candidate for surgery would be a patient with the BAD syndrome, while other factors that suggest surgical management include increased age and poor static lid tone; marked lagophthalmos with severe lower lid paralytic ectropion; strong upper lid retraction in a deeply recessed eye, making it difficult to tape the eyelids shut; monocular vision with the patient depending on the involved eye; difficulty with balance when the eye on the paralyzed side is taped shut; and social factors that make periodic re-evaluation difficult.

Goals of Surgical Therapy The basic goals are to preserve or improve vision, decrease or eliminate exposure irritation, and maintain or improve appearance. Vision is impaired or threatened by the presence of one or more of the following: (1) marked lagophthalmos of the upper and/or lower lid, and/or ectropion or entropion of either lid; (2) poor static lower lid tone, particularly in an older patient who presents with severe ectropion; (3) impairment of tear function resulting in a dry eye; (4) ineffective coverage of the cornea with eye closure as noted with lack of Bell’s phenomenon; (5) loss of corneal sensation due to either exposure hypesthesia or fifth nerve impairment as may occur following resection of an acoustic tumor; (6) progression of staining or other signs and symptoms of irritation of the cornea in spite of maximal medical therapy; and (7) brow droop and/or upper eyelid lash droop.

Figure 6-22. Patient with sixth and seventh nerve paresis following acoustic tumor surgery. A,B, Central tarsorrhaphy originally had been placed to protect cornea and prevent diplopia. Note stretching of tarsorrhaphy bar. When sixth and seventh nerve function failed to return after 2 years, patient asked to have tarsorrhaphy opened. C,D, Appearance of patient after opening of tarsorrhaphy, implantation of palpebral spring in upper lid, and correction of medial ectropion of lower lid. A muscle transposition procedure was also performed to straighten the eye. Note that the spring was left slightly loose to provide a normal palpebral aperture in the primary position. As a result, there is minimal residual lagophthalmos. (From Levine RE.1 With permission.)

The ideal surgical procedure restores lid position and function as well as improves or maintains tear production, distribution, and drainage. This can be accomplished by restoring facial nerve continuity with nerve grafts or using the hypoglossal crossover technique (see Chapters 2 and 3). However, when function is restored by one of these techniques it may take 6 months or longer for neural regeneration to take place, and in the meantime, the cornea is poorly protected and subject to drying. Therefore, the eyelid should be reanimated surgically in such cases to re-establish protection immediately and until the nerve graft or anastomosis begins to function. Further, the patient will benefit from the immediate improvement in eyelid function, and when the results of nerve repair are fully appreciated, the eye reanimation efforts will enhance the final result. Surgical reanimation efforts should be considered even in patients with a favorable prognosis such as Bell’s palsy, if medical measures are not adequate to protect the integrity of the cornea.

Surgical Techniques There are a variety of surgical procedures directed toward improving lid function and appearance when problems in lid closure result from facial paralysis. The reanimation surgeon must be capable of analyzing the variety of problems presented by the patient with facial paralysis and design an approach that will best suit the patient rather than applying his or her favorite procedure for every patient. For organizational purposes, this section will be organized into correcting problems related to the forehead, brow, upper lid, and lower lid, and lacrimation disorders resulting in epiphora as well as the dry eye. The indications, techniques, advantages, disadvantages, results, and complications of each procedure will be discussed with reference to personal experience whenever possible.

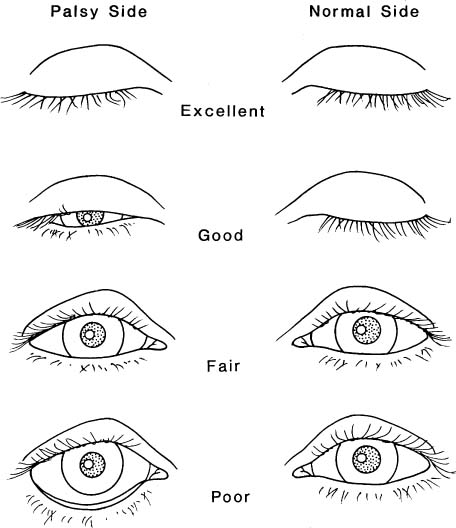

The materials and instrumentation used for the most common procedures performed are listed in Tables 6-4 through 6-9, and the way in which the senior author (MM) reports our results is illustrated in Figure 6-23. Table 6-10 indicates the senior author’s experience with a variety of procedures used to reanimate the paralyzed eye region. The frequency that certain procedures were performed are in keeping with May’s preference based on results achieved.

Forehead

Absence of forehead creases and lack of dynamic expression on the involved side is of greater concern for patients who incorporate eyebrow movement and forehead wrinkling as part of their facial language gesturing. In such cases, conservative management including hairstyle, eyeglasses, and brow makeup is usually adequate (see Chapter 9). The activity of the forehead on the normal side can be toned down or eliminated by botulinum A toxin injections or definitively by a forehead lift approach with resection of the frontalis muscle on the normal side and brow suspension on the involved side.

|

|

|

* The wire, pliers, and cutter can be purchased from Unitek Cork, Monrovia, CA 91016.

Eyebrow

Brow drooping may impair vision when the patient attempts upward gaze. Further, drooping of the brow tends to increase sagging of the supratarsal fold, which in turn may impair upper lid retraction and even overhang the edge of the lid creating a hooding effect. This leads to decreased vision not only in the upward gaze but in the foreward gaze as well.

The drooping eyebrow is corrected with a brow lift. The objective of the brow lift is to provide static symmetry with the normal eyebrow, while avoiding impairment of eyelid closure, which can result from an aggressive brow lift on the paralyzed side. The brow lift also effectively treats lateral hooding caused by the paralytic eyebrow and upper eyelid skin hanging over the upper lash line that may interfere with visual fields of the affected eye. Prior to performing the eyebrow lift, the surgeon must manually evaluate its effect on eyelid closure. Importantly, caution must be taken when combining brow lift with an upper lid blepharoplasty. One may achieve an excellent cosmetic result, but impair eyelid closure. Such errors in judgment have been noted by well-respected colleagues who were not forewarned due to lack of experience with this specialized problem of reanimating the paralyzed eyelid.

|

|

|

Figure 6-23. Classification system to evaluate results of eyelid reanimation surgery.

A useful part of the preoperative planning is to manually hold the paralyzed drooping brow in its normal position and observe whether that impairs eyelid closure. Following this maneuver, it is helpful to gently pinch the excessive skin fold in the upper lid and hold the brow up to see if that impairs eyelid closure. If eyelid closure is not impaired, then this maneuver is repeated in the operating room prior to performing the surgical procedure. These recommendations require that the surgery be done under local anesthesia so that the patient can demonstrate voluntary movement. Usually a gold weight or spring implant is placed into the upper lid following a conservative brow lift with or without a limited upper lid blepharoplasty. The surgeon should not expect the gold or spring to overcome the compromised lid closure created by an aggressive brow lift and/or blepharoplasty procedure.

There are a number of techniques described to correct the drooping brow that include a direct, a midforehead, or a coronal approach.10–13

Direct Brow Lift

Techniques The direct brow lift approach is our preferred technique to manage the drooping brow in patients with facial paralysis. The technique was first described by Beard10 and is illustrated in Figure 6-24. Johnson et al.11 presented and illustrated the technical details of this approach. Clearly the advantage of this technique over the other options is the ability of the surgeon to better control the position and shape of the brow. This is especially advantageous in unilateral brow droop because the surgeon has an opportunity to match the involved side with the normal side. The authors11 demonstrated that the strategic position of the excised skin over the brow, whether it involves the lateral two thirds or is shifted medially, will influence the final position of the brow.

| Total | ||

| Upper Lid | 807 | |

| Gold | 482 | |

| Spring | 325 | |

| Lower Lid | 438 | |

| Tighten | 241 | |

| Cartilage strut | 176 | |

| Tarsorrhaphy | 21 | |

| Lacrimal System | 27 | |

| Partial resection lacrimal gland | 10 | |

| DCR | 10 | |

| Parotid duct transposition | 7 | |

| Other | 337 | |

| Forehead lift | ||

| Brow lift | ||

| Temporalis transposition | ||

| Lid wedge resection | ||

| Closed eyelid spring transposition flaps | ||

| Lysis tarsorrhaphy | ||

| Blepharoplasty | ||

| Punctal plugs | ||

| Punctal cautery | ||

| Lash epilation | ||

| Entropion correction | ||

| Silastic encircling | ||

| Medial canthoplasty | ||

| Inferior retractor recession | ||

| Total | 1609 |

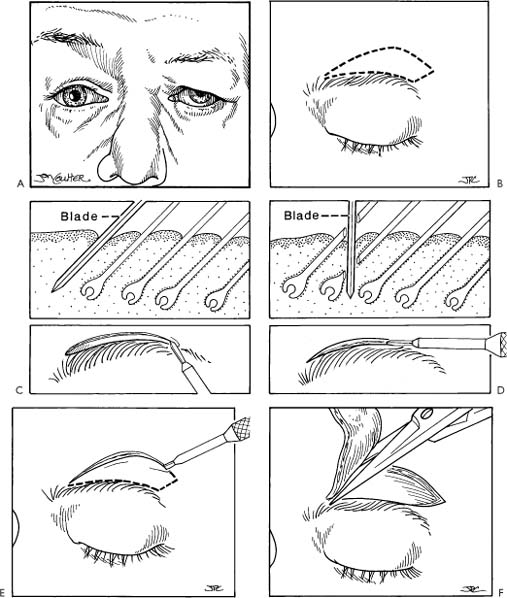

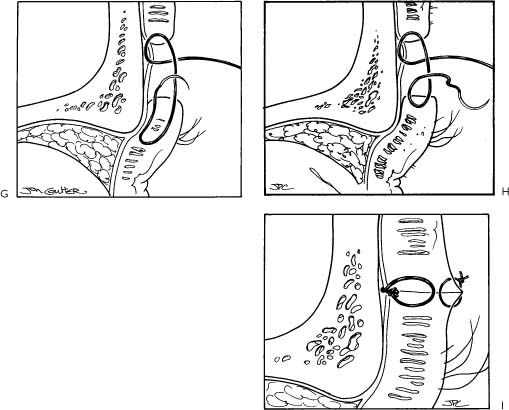

Figure 6-24. Brow lift technique (see Table 6-4 for instrumentation.) A, The level of the brows and the condition of the supratarsal folds are evaluated with the patient in repose and in the upright position. The goal of brow lift is to achieve symmetry at rest between the normal and paralyzed side without impairing eyelid closure. The orbital rim is an excellent fixed landmark to determine the level for brow fixation. Therefore, note is made preoperatively of the relationship of the normal brow to the orbital rim with the patient in repose and in the upright position. This relationship is used to determine point of fixation for the paralyzed side at time of surgery. B, The procedure is performed under local anesthesia. The incision is outline with a marking pencil. Skin resection is not routine and only used in elderly patients with pronounced skin laxity. Usually the incision is limited to just above the brow. The incision should not extend to the lateral or medial limits of the brow to limit scar visibility. C, Correct beveling as demonstrated will protect the integrity of the brow hair follicles as opposed to (D) where loss of brow hair in the incision line will increase scar visibility. E, The incision is made. F, The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and frontalis muscle, if present, are excised down to the suprabrow muscles, thus sparing the supraorbital nerve and vessels. G, 4-0 Nurolon is used to fix the lower margin of the wound to the peristeum at a level that corresponds to the orbital rim determined preoperatively. This suture is key to securing the paralyzed brow to a level that will match the normal side. The supraorbital fold is suspended, if required, by incorporating this periosteal fixation suture with the supraorbital fold and periorbicularis oculi muscle as recommended by Luxenberg (1973).62 Two or three of these sutures are placed to recreate the horizontal configuration of the normal side. H, The closure for patients without supratarsal fold droop. I, The wound is closed with subcuticular running sutures, and then the skin is closed with a running locking 6-0 chromic suture. Note the wound edges are everted. Steri-strips are then applied. The pull-out subcuticular suture is removed in 14 days. In patients with facial paralysis, the brow lift is usually combined with upper and lower lid procedures. A word of caution: Be conservative in the amount of brow lift in patients with facial paralysis as opposed to patients operated for cosmetic purposes. Be sure the brow lift does not impair eyelid closure. One must preserve function even if appearance is compromised (see Fig. 6-25).

Once the position of the brow is determined, the next key to success is to fix the lower wound edge with 4-0 clear monofilament permanent suture material to the periosteum under the edge of the upper incision line. The periosteal fixation was stressed by Beard.10 Two or three sutures are placed to ensure that the new level of the suspended brow will be maintained.

Care must be taken when dissecting medially to expose and not disrupt or unnecessarily traumatize the neurovascular bundle of the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves and vessels. Meticulous wound closure ensures that the resulting scar will be barely preceptible.

Drooping or sagging of the supratarsal fold can be corrected to some degree by including a portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle or soft tissue under the supratarsal fold. The orbicularis oculi muscle underlying the supratarsal fold is included with the needle and suture just before it passes through the tissue of the lower wound edge. Then, upon tying down the suture, the supratarsal fold will be suspended with the new position of the brow.

As a general rule the orbital rim is a good landmark for placing the brow; in men, the brow should be placed on the orbital rim, while in women, the brow should be placed above the rim. The actual position of the brow as well as its form should match the normal side in the position of rest and should be determined with the patient in the upright position. Preoperative photographs placed where they can be viewed by the surgeon during the procedure is quite helpful as a reference to achieve the best results.

Complications A noticeable scar in the hair line along the incision can occur but can be avoided when the recommendations provided have been followed. In the event that the scar is noticeable, it can be easily covered with a pencil liner or hairstyle in the case of women, and eyeglass wear is always an effective camouflage measure in men.

Another complication of brow lift is overcorrection. This can be revised by going back and releasing the fixation sutures in order to reposition the brow so that the paralyzed side and normal side have a more symmetrical appearance. In Figure 6-25, a patient post-Bell’s palsy was referred to correct problems created by the referring surgeon. The combination of an aggressive brow lift and upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasties impaired the patient’s ability to approximate the eyelids on the paralyzed side.

Hematoma and infection have not been a problem in any of the cases.

Results Overall this is a very rewarding procedure to achieve brow symmetry and help restore supratarsal fold position (Figure 6-26).

Endoscopic Brow Lift We have successfully used an endoscopic technique developed by Patel and Anderson8 to elevate the brow in 12 patients with facial palsy. We use a two-incision approach with a paracentral radial incision and a circumferential incision over the temporalis fossa. A wide subperiosteal dissection is performed through the paracentral incision. The temporal dissection is between the superficial and deep temporal fascia. Two planes are connected over the temporal fusion line. The endoscope is used to divide the periosteum from the entire supraorbital rim. This release is extended over the lateral orbital rim as well, thereby forming a composite flap that is freely mobile. The endoscopic method of brow elevation relies on complete mobilization and refixation of the mobilized flap in the new position. Release of the periosteum, which is important in all endoscopic brow elevations, must be especially complete in patients with facial palsy. The superficial temporal fascia is firmly attached to the lateral orbital rim and has been called the orbital ligament. This attachment limits the cephalad movement of the superficial temporal fascia and needs to be completely released. In some patients, we dissect over the superior and lateral orbital rim via an upper eyelid skin crease incision, and ensure the creation of a completely mobile flap. This approach is particularly useful in men with heavy forehead tissues.

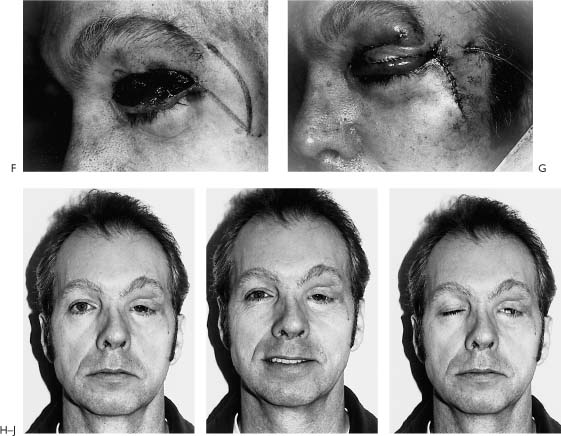

Figure 6-25. Complication of overly aggressive surgery for patient post-Bell’s palsy. Brow lift and upper and lower blepharoplasties were performed to improve appearance, but impaired eyelid closure. The patient had chronic exposure keratoconjunctivitis. A, Repose. B, Smiling. C, Attempting to close eyes. Note upper lid retraction on involved left side. Surgical correction was performed with Dr. George Buerger. D, Through tarsal-supratarsal fold incision, scar tissue was removed exposing levator palpebral superioris muscle. This muscle was recessed to allow more upper lid downward excursion. E, An eyelid spring was implanted to counter the tendency for the lid to retract. F, A pedicled flap was transferred into the upper eyelid to replace tissue removed by previous blepharoplasty. G, Wound closed. H,I,J, Results 2 months postsurgical correction. This case is a reminder and a warning to the reanimation cosmetic surgeon that the brow and eyelid in patients with compromised facial motor function require special consideration.

Once the composite flap has been mobilized, fixation in the new position is necessary. We have tried many fixation systems in functional, cosmetic, and facial palsy brow ptosis correction. The method that works best for us and for our patients with facial palsy is the use of the Mitek screw and suture system (see Chapter 7 for more details regarding the Mitek suture system). The screw is a self-retaining system with a suture attached to it. Once the screw has been placed, free needles are used to insert the sutures into the composite flap and elevate it to the required height. Other methods that also work well for fixation include the use of absorbable screws around which the sutures are tied and drilling a cortical tunnel through which the sutures are passed and tied. We generally aim to overcorrect the position of the brow in patients with facial palsy, as some degree of descent of the forehead and brow always occur. Additional sutures from the released superior orbital rim periosteum may be sutured to the Mitek screws or to the periosteum and galea posterior to the scalp incisions. The lateral aspect of the brow is elevated by suturing the superficial temporal fascia of the mobilized flap to the fixed deep temporal fascia. It is important to remember that the contraction of the occipitofrontalis that is thought to contribute to the mobilization and refixation of the forehead in the form of an extensive myocutaneous flap particularly pertinent. To date, we have had excellent results with this system in most patients. In our earlier patients, we tended to lift the forehead and brow as with cosmetic patients, and this invariably led to an undercorrection. Since then, in spite of an attempt at marked overcorrection, we have yet to see an overcorrection (Fig. 6-27). We have had no infections or palpable screws.

Figure 6-26. Results of brow lift with elevation of supratarsal fold and upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasty. The correction was for facial paralysis following a partial temporal bone resection for cancer of the external ear canal. A, In repose. B, Raising eyebrows. Only normal right side elevates. Note the marked sagging of the supratarsal fold that covers the upper half of the cornea in forward gaze. One month post-reanimation: C, In repose. D, Closing eyes. Note marked improvement (see Fig. 6-41).

Advantages of this method include the presence of small scars on the scalp and temple where they may be hidden by hair. Even when there is no hair, the scars are barely visible. Disadvantages include the need for expensive, specialized instrumentation and the lack of long-term results.

Upper Eyelid

There are a number of approaches to improve upper eyelid closure. The nonsurgical approaches have been discussed in the medical treatment section. In addition to the most common techniques including gold and spring implantation, there are other adjunctive measures that may be done alone or in combination, including levator muscle recession or, even in some cases, plication, muscle of Mueller resection, medial and lateral canthoplasty, or modified tarsorrhaphy.

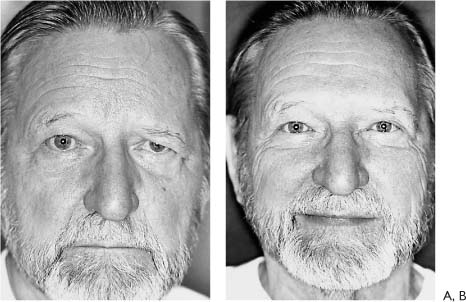

Figure 6-27. Endoscopic brow lift in facial palsy. A, A 67-year-old male with a left facial palsy which has been present since the age of 4 years. Note the marked forehead ptosis with severe brow ptosis, secondary hooding of the upper eyelid, lash ptosis, and visual obstruction. B, Six months following a left endoscopic brow elevation. A paracentral incision, a temporal incision, and an upper eyelid crease incision were used to mobilze the composite forehead flap.

Resection of Müller’s muscle has been recommended for the treatment for thyroid related upper eyelid retraction.14 Based on this information, one might consider combining resection of the Müller’s muscle with or without recession of the levator papebral superioris aponeurosis to overcome upper lid retraction in the process of reanimating the paralyzed upper eyelid. There are an anatomical and physiologic bases for resection Müller’s muscle in thyroid lid retraction, but none in cases of facial paralysis without thyroid disease.

Gold Weight Implantation In 1950, Sheehan15 inserted a band of tantalum into the upper eyelid to affect closure and referred to this as lid loading. Illig16 is credited with the first gold weight insertion, and almost 10 years later, an English surgeon Smellie17 reported his experience using the gold weight to reanimate the upper eyelid. Jobe18 was the first American surgeon to report using the gold weight and is responsible for popularizing the procedure in the United States. Implantation of a weight worked quite well in principle and was appealing because of its simplicity.

However, as one would expect with the implantation of a foreign body in the upper eyelid where the skin is so thin and delicate, extrusion is a problem. Many efforts have been made to overcome this shortcoming. Suggestions have been made to encase the gold weight in silicone rubber,19 to customize fabrication of the gold implant prosthesis for each patient’s needs,20 and as suggested by Kaplan et al.,21 to customize the weight, size, and shape of each implant before surgery in order to achieve the best results. Barkley and Roberts22 presented in great detail their laboratory technique used to manufacture the gold weight implant. They stressed that of all of the implant materials available, gold is preferred because it is inert, has a high tissue tolerance, and is quite malleable and easily manipulated to form into the required shapes. The density of the gold weight allows a relatively small volume to achieve eyelid closure, and the 24-carat gold used for implantation has a satisfactory color and tends to blend with the skin tone.

Professor Micheli-Pellegrini23 commented that he had already published three papers on this subject in the Italian literature. In his 1967 article, he stressed the importance of fenestrating the gold implant in order for tissue to grow through it and prevent subsequent extrusion, as already reported by Jobe.18 Jobe emphasized the importance of fitting the patient with the proper weight and made available a standardized kit containing different weights that had holes drilled in the prosthesis for suture fixation and details of surgical technique that ensured a high success rate.

In spite of Jobe’s report, the gold weight procedure intially did not gain popularity because of a high failure rate and complications noted by other surgeons. Pickford et al.24 reported their experience with 54 patients. Five suffered spontaneous loss of their gold implants, and 16 reported problems attributable to the weight itself: (1) unsightliness due to bulging through the lid, (2) redness of the upper eyelid skin, (3) distortion of lid shape, and (4) soreness, particularly after minor trauma. Two patients reported that their implant had shifted medially within the lid. It was interesting that two out of the five patients in whom the implant extruded had undergone previous lid surgery, suggesting that there is a greater risk in such cases. A small number of their patients required revision surgery to replace the implant with a lighter one. Patients developed a drooping eyelid that was thought to be due to a condition referred to as levator fatigue. In an attempt to explain their high complication rate, the authors stressed the importance of a correct plane for the pocket into which the implant is placed and suggested that a superficial placement may contribute to ulceration or migration.

The gold weight implant used by these authors did not have fenestrations for suture fixation, and the design of the weight has been modified by making it somewhat longer and flatter in an attempt to reduce the unslightly bulging. It is quite possible that their high complication rate was related to the design of their implant.

A report by Kelly and Sharpe25 reported an extrusion rate of 43% and an overall complication rate of nearly 70% in 31 patients. This unacceptable rate of morbidity could possibly be attributed to the lack of adherence to the principles outlined in Jobe’s original article.18

Jobe’s Recommendations We have achieved a high success rate and low incidence of complications by paying meticulous attention to the details in Jobe’s 1974 article. Jobe stressed the importance of preoperative fitting of the prosthesis by testing the lid with different weights. He described temporarily cementing the gold weight to the patient’s lid with tincture of benzoine. The patient was sitting upright for the procedure, and was asked to look up and down. The size of the weight was changed until the desirable prosthesis was determined by noting which size held the lid about 1 mm lower than the normal lid when the patient looked straight ahead. The overcorrection was in anticipation of levator palpebral superioris strengthening once the weight was in place. Finally, when a proper weight has been chosen, it must be cleaned with soap and water, rinsed thoroughly, and then autoclaved in preparation for use.

In his classic article, Jobe highlighted the surgical procedure.18 He suggested that the prosthesis be centered at the juncture of the medial and central third of the lid. We have found that this is a key point because the eyelid closes from lateral to medial. Unless the gold is placed just medial to the midline, a common problem is persistent exposure of the medial third of the globe. Jobe stressed that the plane into which the prosthesis is to be placed is on the surface of the orbital septum, and the tarsal plate and the lower edge of the prosthesis should be a few millimeters above the lid margin. This prevented extrusion of the gold through the lid. Further, if the prosthesis was placed in this deep plane, there was maximum tissue to cover the implant. This not only decreased the likelihood of extrusion, but also made it less likely that the gold would show through the thin tissues. By placing the gold a few millimeters above the lid margin, the very thin, tightly adherent skin of the lower margin of the tarsus is avoided. In addition, the likelihood of the gold migrating inferiorly and prolapsing over the lashes was prevented.

Another reason for extrusion and migration was failure to suture the prosthesis to the orbital septum with nonabsorbable suture. Finally, the skin as well as the orbicularis oculi muscle must be closed. In the event that the patient has long-standing facial paralysis and the muscle is fibrotic or there is only a fascial layer between the skin and the tarsus, this layer must be closed. In other words, there should be a two-layered closure over the prosthesis.

Jobe has continued to champion the use of gold weights and is responsible for the commerical availability of this product through the Meddev gold eyelid implants. As medical director of Meddev Corporation, Jobe responded to a report by Biar et al.26 regarding three cases with gold sensitivity following insertion of gold eyelid weights. Jobe conceded that sensitivity, even to pure gold produced by the Meddev Corporation, had been observed on a rare occasion. These cases can be successfully treated with either corticosteroid injection, or as reported by Biar et al.,26 in one case, with replacement of the gold weight with a Meddev implant constructed of pure platinum. We have had one case out of 482 implants where the gold had to be removed because of tissue intolerance or perhaps a patient sensitivity to the gold.

Combined Procedures Combining other reanimation procedures with the gold weight insert should be considered as part of a total program in rehabilitating eyelid closure. Jobe18 commented that in patients with long-standing facial paralysis, the gold weight implant patient may require augmentation with other procedures such as lateral canthoplasty, brow lift, lower lid shortening procedures for ectropion, lower lid supporting procedures with fascia slings, or medial canthoplasty. In addition to lower lid tightening procedures, Gilbard and Daspit27 enhanced their results by adding recession of the lower lid retractor muscle, placement of fascia lata combined with a lateral tarsal strip tightening procedure, and sectioning of the muscle of Müller as a reliable approach for mimicking involuntary blink without ptosis.

Possible Contraindications In their discussion, Linder et al.28 mentioned glaucoma as a contraindication for lid-loading devices, although there appears to be no significant alteration of the intraocular pressure with this technique as reported by Kartush et al.29 They also mentioned the concern for the effect of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on patients after gold weight insertion, considering that many of these patients require reanimation following acoustic tumor surgery and MRI is the most useful method for following acoustic patients postoperatively. This problem was studied by May et al.30 and Marra et al.31 Based on these two reports, MRI is not a concern for patients with gold weight insertion because the gold is not magnetized. Patients may be aware of some increased heat, and this can be easily countered during the MRI examination with application of a eye patch saturated with water and placed over the involved eye.

Gold Weight for Patients with Other Procedures So far no mention has been made of a gold weight implant for patients who have a tarsorrhaphy in place or the effects of other procedures that would influence eyelid movement such as a Silastic encircling procedure.32 Liu33 discussed this problem and made some important observations regarding case selection. First, the author stressed the importance of determining which eye is dominant because this will influence height of the reanimated eyelid. Second, in order to obtain an accurate weight of the implant needed, the restrictive effect on the eyelid from the previous surgery, such as tarsorrhaphy or encircling band, must first be eliminated. Third, he stressed the importance of evaluating the patient’s lacrimal function, Bell’s phenomenon, and levator function in order to predict the best result as well as the patient’s likelihood of significant improvement in eye comfort. The goal of eyelid implantation is to improve upper lid position in order to protect the otherwise exposed cornea. In the process, a mild amount of ptosis may occur. This may be acceptable as long as it does not interfere with vision. Factors such as the height of the upper eyelid will be influenced by which eye is dominant, the effect of the previous procedure, and finally the function of the levator muscle.

Liu33 in an effort to explain the role of the dominant eye introduced the concept of Hering’s law of equal innervation. If the level of the eyelid interferes with vision in the dominant eye, then the patient tries to raise that eyelid. As a result, there is extra innervation going to both upper eyelids. Consequently, the palpebral fissure of the normal eye will be wider than its normal width. When the first procedure is undone as would occur if a tarsorrhaphy was taken down, the vision in the dominant eye would not be interfered with and the extra innervantion would no longer be present. In such a case, the normal nondominant eyelid would lower.

The same effect would occur if a gold weight implant was placed in the paralyzed eyelid, and the level of the lid with the gold was lowered to the point where it interfered with vision. Then Hering’s law of equal innervation would come into play, causing the normal eyelid to retract. Even with the increased innervation to the involved side, the levator muscle would not be able to overcome the forces of the gold. Thus, the normal eye would be wider, and the involved eye with the gold weight would be ptotic.

Therefore, when the gold weight is placed, it is important to first determine which is the dominant eye. It is also important not to place a weight that will lower the lid to the point where it interferes with vision. This well-known phenomenon among ophthalmologic surgeons is not one that is commonly known outside of that specialty, and for that reason, it is included in this general discussion of gold weight implantation.

It should be obvious that one cannot evaluate the effect of the gold implant by pasting it on the eyelid until the first procedure is undone. The tarsorrhaphy or the encircling band will hold down the upper eyelid, and in such a case, it would seem that less weight is needed to close the eyelid. Evaluation of the proper weight as well as levator function cannot be evaluated as long as the restrictive effect on the lid is in place. Therefore, the correct approach is to take down the tarsorrhaphy first and then re-evaluate not just the proper weight of the gold but what procedure or procedures would be best for the patient (Figure 6-28).

Timing of Reanimation Surgical treatment for the paralyzed eyelid should be delayed following facial nerve injury. There are changes that occur over the first 14 days following total facial paralysis that must be taken into account when considering reanimating the eye region. Following total interruption of the facial nerve as occurs with acoustic tumor surgery, the patient seems to be able to close the eye in the immediate postoperative period. This suggests that the injury to the facial nerve is incomplete and is a source of misinterpretation. The eyelids will almost approximate during this time period based on maintenance of the integrity of facial muscle tone. Complete Wallerian degeneration takes 10 to 21 days, at which time the periorbicularis oculi muscles will begin to lose their tone and gravity will begin to affect the position of the lower lid leading to ectropion. At this time, it will become obvious that the lids are not approximating. Therefore, it is best to wait until the effects of denervation have occurred and, in the meantime, manage the patient with medical measures as discussed earlier in this chapter.

Author’s (MM) Experience with Gold Implants The first gold implant was placed in February 1983 under the direction of Dr. Bill Swartz. Until that time, the wire spring implant taught to me by Dr. Bob Levine was my preferred approach to upper eyelid reanimation. My experience with the gold placement procedure in terms of its simplicity, the commercial availability of the prosthesis, and the consistently favorable outcome achieved, convinced me that this technique had many advantages over using a spring. It is interesting to note that in 1987 we reported our experience with gold weight and wire spring implants as alternatives to tarsorrhaphy.34 A total of 139 wire springs and 90 gold weights were implanted in 202 patients. Now, 10 years later, the preference for gold over the spring is reflected in Table 6-10, where the accumulated experience shows 482 gold implants compared to 325 spring implantation procedures. The material previously reported in 198734 will be updated in this section (Table 6-11).

Patient Selection The ideal candidate for gold implant (Fig. 6-29) has the following characteristics:

- The patient has facial paresis rather than total paralysis. In such cases, the patient can achieve partial closure of the eyelids.

- The patient has total paralysis with some lowering of the upper lid with an effort to close the eyes.

- The supratarsal fold is prominent and allows for placement and coverage of the gold implant.

- The upper lid approximates or at least covers the cornea with a properly chosen gold weight pasted on the involved eyelid with the patient in the upright position and the lid position is symmetric with the normal side when the lids are opened.

- The eyelids approximate when the patient is lying down with the head on two pillows and the gold weight is pasted on the involved upper eyelid.

- The patient has a good Bell’s phenomenon (Fig. 6-7), tears are present, and there is normal corneal sensation (absence of the BAD syndrome).

- The patient is compliant regarding eye care and practicing suggested maneuvers that improve the eye closure effect of the gold weight (looking down when attempting to blink or “think blink” and reading with material held at eye level to control involuntary ptosis).

Now that we have presented the characteristics of the ideal patient, one can predict who would be a poor candidate (Fig. 6-30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree