THE EVALUATION OF ORBITAL DISEASE

Peter Heyworth and Geoffrey E. Rose

The aim when evaluating orbital disease is to localize and characterize the pathological process so that management may be planned. The history and examination findings may be recorded on a standardized sheet to encourage a systematic approach to analysis of these rare diseases.

HISTORY

The principal symptoms of orbital disease are pain, change of vision or double vision, and lid swelling or globe displacement. A detailed history should be taken and enquiry should be made about previous sinus disease and surgery, endocrine dysfunction, immunological disease, malignancy, infections, and trauma.

The temporal dynamics of symptoms will often indicate the nature of the disease. A rapid onset of symptoms—such as pain and swelling—would suggest acute inflammation due to infective cellulitis or other acute event, such as a hemorrhage into an orbital varix. In contrast, gradually worsening diplopia in the absence of pain would suggest the relentless progression of an orbital mass, such as that caused by a benign mixed tumor of the lacrimal gland. The rapid and simultaneous loss of multiple functions (both sensory and motor) implies an inflammatory process, whereas progressive sequential loss is more indicative of an infiltration by, for example, malignant tumors.

The order in which symptoms occur may suggest the position of an orbital mass. Whereas an anterior orbital mass will cause diplopia and displacement of the globe before affecting visual acuity, a tumor at the orbital apex or in the canal (such as a glioma) will tend to cause visual loss prior to the onset of diplopia or a mass effect.

The nature of pain gives a clue to the cause: with orbital myositis there is often a backgroundperiorbitalache occur when the gaze is directed away from the field of action of the affected muscle. In contrast, the pain associated with invasive malignancy, such as lacrimal gland carcinoma or metastases, tends to be relentless and may be associated with sensory loss as local nerves are invaded.

EXAMINATION

GENERAL FACIAL INSPECTION AND ORBITAL PALPATION

Examination should start with a general inspection of the face, looking at facial contour, especially for asymmetry, and changes in the lids, such as swelling, erythema, or loss of the upper lid sulcus or skin crease (Fig. 15-1). The temporalis fossa should also be examined for either wasting or fullness (Fig. 15-2A,B). Localized skin changes, such as discoloration, may indicate underlying orbital vascular anomaly, whereas skin infiltration may occur with systemic lymphoma (Fig. 15-3A,B) or sarcoid (Fig. 15-4). Facial weakness should be recorded, with particular attention being paid to the presence of frontalis sparing, which indicates an upper motor neuron (central) facial nerve palsy. Hearing should be checked with all facial nerve lesions, this being readily tested clinically by rustling two fingertips together near the patient’s ear.

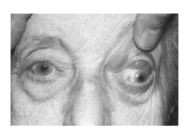

FIGURE 15-1 Loss of upper lid skin crease and hypoglobus due to an orbital mass. (See Color Plate 15-1.)

FIGURE 15-2 (A,B) Examination of the temporalis fossa for wasting (A) or a mass (B) may provide diagnostic clues for orbital disease. (A) Temporalis wasting due to chordoma affecting the orbit and trigeminal ganglion. (B) Dermoid of the right orbit and temporalis fossa. (See Color Plates 15-2A,B.)

The vertical palpebral aperture and the position of the lids (relative to the cornea) should be noted; scleral “show” at the upper limbus being due to either primary levator overaction—typically due to thyroid eye disease—or fibrosis within the levator muscle. Without prior inferior rectus recession, lower scleral show (often misleadingly termed lower lid “retraction”) is almost exclusively due to proptosis, rather than overaction of the lower lid retractors. The dynamics of the lids should be assessed, particularly levator excursion and the presence of lid lag or lagophthalmos; lid lag being almost exclusive to thyroid eye disease. The lids should be everted and fornices examined to look for underlying diseases, such as fat prolapse, lacrimal gland enlargement, or the characteristic salmon patch of orbital lymphoma (Fig. 15-5).

FIGURE 15-3 (A,B) Left orbital mass (A) with cutaneous involvement (B) due to a T cell lymphoma. (See Color Plates 15-3A,B.)

The orbital margins should be palpated for discontinuity, which may occur with fractures or developmental abnormalities. The shape, size, surface texture, and deep attachment of an orbital mass should be assessed; if not initially felt, it may present to palpation by being carried forward in relation to a neighboring extraocular muscle when the patient looks away from the area of palpation (Fig. 15-6A,B). Likewise, posterior ballottement of the globe may displace forward an otherwise elusive, or impalpable, orbital lesion. Extension of a mass into the temporalis fossa (Fig. 15-7), or involvement of local lymph nodes, is important in the planning of treatment. Variation in proptosis with Valsalva maneuver (Fig. 15-8A,B), or a filling-and-emptying of the mass with pressure (Fig. 15-9A,B), may indicate a low-pressure vascular malformation or a meningocele.

FIGURE 15-4 Enlarged lacrimal glands due to sarcoid in a patient with perinasal skin involvement. (See Color Plate 15-4.)

FIGURE 15-5 Subconjunctival lymphoma presenting as “salmon patch.” (See Color Plate 15-5.)

FIGURE 15-6 (A,B) Orbital masses related to the globe may be more evident in certain positions of gaze. Lower lid swelling due to a mass on the inferior surface of the globe, just visible in primary position (A). It is readily evident on up-gaze (B). (See Color Plates 15-6A,B.)

FIGURE 15-7 Ballottement of the globe may demonstrate communication between the orbit and temporalis fossa. Pressure on the right globe displaces the contents of a dumbbell dermoid from the orbital component into that of the temporalis fosssa, with swelling of the fossa at the site of the previous incision. (See Color Plate 15-7.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree