CHAPTER 10 Effect of Pregnancy on Other Skin Disorders

Introduction

Pregnancy causes immunologic, endocrine, metabolic, defined, and vascular changes in the pregnant woman which modify her responses to skin diseases. Both the obstetrician and the dermatologist need to be aware of this if they are to provide optimal management during pregnancy. Particular attention should be given to any medication administered to a pregnant or nursing woman; the reader is advised to consult published guidelines and/or review articles1–6.

Psoriasis

Types of psoriasis

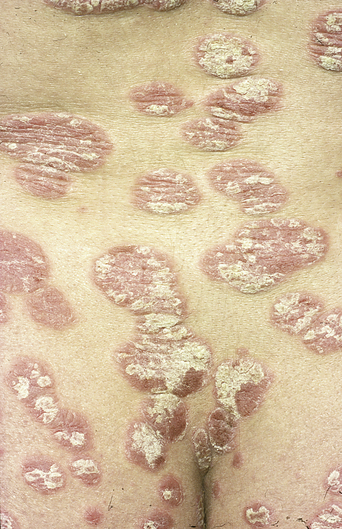

In plaque-type psoriasis, the commonest form of psoriasis, there are well-demarcated erythematous plaques with adherent silver scales on the surface. The lesions are most common on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the sacral area (Figure 10.1), and the scalp (Figure 10.2). The groin may also be involved.

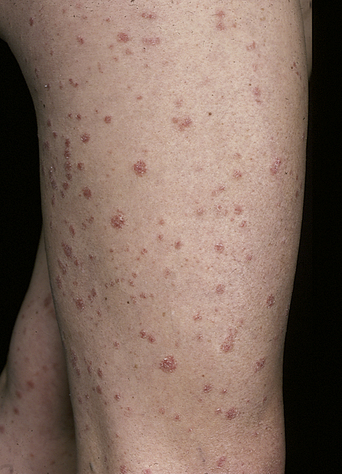

Guttate (drop-like) psoriasis is characterized by scattered pink papules, which are of uniform size and flare in crops mainly on the trunk (Figure 10.3) and proximal extremities. It often follows an upper respiratory infection, especially with streptococci. In erythrodermic psoriasis, the skin is red with a fine desquamative scale present, often over its entire surface. There are several forms of pustular psoriasis, in which small sterile pustules appear either on pre-existing plaques or de novo on normal skin. Most patients with pustular psoriasis have had psoriasis previously. Generalized pustular psoriasis (von Zumbusch) may be life-threatening, and treatment is urgently required (Figure 10.4). Fever, arthralgia, and leukocytosis often accompany the eruption. Pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles (palmoplantar pustulosis) consists of sterile itchy pustules on an erythematosquamous background.

The effect of pregnancy on psoriasis is unpredictable, although in most cases it improves. In up to 15% of women psoriasis worsens. It can also flare postpartum, usually within 3–4 months of birth. CD4-positive T-helper cells are capable of differentiating from an initial common state into two distinct types called TH1 and TH2 lymphocytes (see Chapter 3). These subtypes differ in their cytokine secretion. TH1 lymphocytes secrete interferon-gamma and interleukin-2, whereas TH2 lymphocytes secrete interleukins-3, 4, 5, 10, and 13. There is negative feedback so that a TH1 response inhibits the TH2 pathway and vice versa (see Figure 3.20 in Chapter 3). In psoriasis proinflammatory TH1 cytokines are upregulated and play a key role in the mechanisms of chronic inflammation. In pregnancy there is a shift from TH1 to TH2 immunity in the placenta that promotes fetal survival by decreasing the TH1 responses involved in rejection of the fetus as an allograft 7.Thus during pregnancy many of the TH1-mediated autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis improve by downregulation of the TH1 proinflammatory cytokine response8–10. It has previously been postulated that high levels of progesterone would correlate with improvement of psoriasis11. In a recent study comparing 47 pregnant women with psoriasis with 27 controls (nonpregnant women with psoriasis), high levels of estrogen correlated with an improvement in psoriasis whereas progesterone levels did not correlate with psoriatic change12.

Pregnancy

Topical dithranol, tar, calcipotriol, topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus appear to be safe choices for control of localized psoriasis in pregnancy13. UVB is the safest treatment for extensive psoriasis during pregnancy when topical therapy is not practical. Short-term use of cyclosporine during pregnancy is probably the safest option for the management of severe psoriasis that has not responded to topical therapy or phototherapy or for severe pustular psoriasis in pregnancy13,14.

Ultraviolet B and psoralen with ultraviolet A

UVB irradiation is safe in pregnancy, but the patient should be aware that UVB can increase the size and number of benign pigmented nevi. Narrowband UVB (TL01) has recently been successfully used for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy15. The use of PUVA may carry a risk of mutagenesis and teratogenesis, and neither systemic nor topical (bath) PUVA should be used as a first-line treatment in pregnancy. However, a large study by Gunnarskog et al.16 found no increased risk of spontaneous or induced abortions, nor an increased risk of congenital malformation or infant death, including pregnancies conceived following PUVA treatment.

Systemic drugs

Systemic drugs are sometimes required to treat psoriasis. Retinoic acid (acitretin) is highly teratogenic and should be used with caution (see below). Several cytotoxic drugs have been used for psoriasis, including methotrexate, hydroxyurea, and azathioprine. Methotrexate and hydroxyurea are known teratogens and must therefore be avoided in pregnancy, and azathioprine may be teratogenic. Cyclosporine A can be used with caution in pregnancy and during breastfeeding and is a safer alternative to oral retinoids17 or methotrexate.

The newer biological treatments – antitumor necrosis factor agents and efalizumab – are not currently licensed for use in psoriasis during pregnancy18.

Course of disease

The hormonal changes in pregnancy do appear to influence the severity of psoriasis (Table 10.1)19. About 75% of women notice a significant change in their psoriasis during pregnancy, with 60% showing improvement and 15% an exacerbation; 80% of these will experience a postpartum flare of their diseases, usually within 4 months of delivery11. Pregnancy may also be a risk factor for psoriatic arthritis20.

Table 10.1 Key Points for Psoriasis in Pregnancy

| Psoriasis generally improves in pregnancy (60%) |

| Topical corticosteroids, dithranol, tar, calcipotriol, and topical tacrolimus are safe in pregnancy for localized disease |

| Phototherapy (ultraviolet B (UVB), narrowband UVB and psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA)) can be used in more extensive disease |

| Severe pustular psoriasis may need oral corticosteroids or cyclosporine |

| Oral retinoids and methotrexate are contraindicated |

| Biological therapies (antitumor necrosis factor agents and efalizumab) are not currently licensed for use in psoriasis during pregnancy |

| 80% of affected patients will flare postpartum |

Impetigo herpetiformis

Impetigo herpetiformis is generally regarded as a very rare, acute, pustular form of psoriasis precipitated by pregnancy (Table 10.2). It can affect pregnant women with no previous history of psoriasis. The onset is usually in the third trimester, and the disease tends to persist until delivery but may continue thereafter.

Table 10.2 Key Points for Impetigo Herpetiformis

| A form of pustular psoriasis in pregnancy |

| Presents in the third trimester and may recur in subsequent pregnancies (earlier onset and with increased severity) |

| Increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and fetal abnormalities due to placental insufficiency |

| Maternal constitutional upset – with fever, delirium, tetany, vomiting, and diarrhea |

| Hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism (reduced intestinal absorption of vitamin D) |

| Treatment is with oral corticosteroids or cyclosporine |

| Recent evidence suggests treatment with vitamin D and calcium may be helpful |

The eruption characteristically begins in the flexures with small sterile pustules on areas of acutely inflamed skin. These then extend centrifugally on to the trunk (Figure 10.5) and around the umbilicus (Figure 10.6) or form plaques with green-yellow pustules. The eruption may advance and become widespread, involving the tongue, buccal mucosa, and sometimes the esophagus. Constitutional symptoms are common, including fever, delirium, vomiting, diarrhea, and tetany due to hypocalcemia. Death may occur as a result of cardiac or renal failure.

The main obstetric problem in impetigo herpetiformis is placental insufficiency, with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and fetal abnormalities21. The disease characteristically recurs with each pregnancy, with earlier onset and increased morbidity21. Between pregnancies, patients are free of the disorder and have no manifestations of psoriasis. The disease may also be exacerbated by oral contraceptives22 and has also been described in association with Staphylococcus aureus lymphadenitis23. In severe cases, termination of pregnancy is required; the impetigo herpetiformis usually resolves soon afterwards. Although the etiology of this condition is still unclear, a recent report showed extremely low levels of epidermal skin-derived antileucoproteinase/elafin in a patient with impetigo herpetiformis24. An association with hypoparathyroidism and reduced intestinal absorption of vitamin D is thought to be the mechanism for reduced serum calcium levels25. A recent case of impetigo herpetiformis with compensatory hyperparathyroidism and normocalcaemia has been described26.

Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for impetigo herpetiformis, but the results are generally unsatisfactory. Cyclosporine has also been used successfully in treating this condition27. Calcium and vitamin D have also been used successfully in treatment28. If the disease persists postpartum and is severe then oral retinoids may be used for treatment.

Acne vulgaris

Although acne may improve in pregnancy, it is occasionally exacerbated (Table 10.3). This usually causes management problems, as most antiacne drugs are contraindicated during pregnancy. However, topical antiacne therapy, other than topical retinoic acid and salicylic acid, does not seem to be teratogenic. Topical antiacne therapy which contains salicylic acid should be used cautiously or avoided during pregnancy and lactation as these products can cause salicylism, and absorption from breast milk in nursing infants could in theory cause bleeding29. Animal data support the avoidance of topical known teratogens such as retinoids and salicylic acid in pregnant women29. Acne conglobata developing 10 days postpartum has recently been reported30. Acne neonatorum has also been described with a family history of hyperandrogenism31.

Table 10.3 Key Points for Acne in Pregnancy

| Acne vulgaris often flares in the third trimester when sebaceous gland activity increases |

| Topical benzoyl peroxide and azaleic acid appear safe for use in mild comedonal acne |

| Erythromycin is the safest oral and topical antibiotic for treatment of acne in pregnancy |

| Systemic and topical retinoids are contraindicated in pregnancy |

| Rosacea fulminans can flare in pregnancy and usually requires treatment with oral erythromycin and oral corticosteroids |

Acne rosacea often flares during pregnancy and may also require treatment with topical or systemic antibiotics. There is a rare severe variant called rosacea fulminans (or pyoderma faciale) presenting in pregnancy which is characterized by a severe facial eruption with papules, nodules, pustules, and erythema. This normally requires treatment with oral erythromycin and oral corticosteroids. A recent case of rosacea fulminans complicated by stillbirth has been reported32.

Management

The treatment of acne depends on the type of acne involved. If only comedones are present, a keratolytic agent such as benzoyl peroxide (2.5–10% cream, lotion, or gel) or azaleic acid cream 20% should be used to remove the surface keratin and unplug the follicular openings. These drugs are safe to use in pregnancy but products containing topical salicylic acid are best avoided29. Topical retinoic acid has been reported as causing multiple congenital defects33. Ultraviolet light has an effect similar to that of topical keratolytics, but should be avoided in pregnancy.

Antibiotics

Long-term antibiotic therapy is usually required for inflammatory lesions with papules, pustules, or nodules. However, acne is slow to improve and beneficial effects are not usually seen for at least 2–3 months, with gradual improvement after 6–12 months of therapy. Maintenance treatment must be continued until the acne improves. Oral tetracycline is associated with maternal liver toxicity and deciduous tooth staining in the infant and tetracycline has also been associated with congenital anomalies34. Oral erythromycin is safe in pregnancy and is given at a dose of 250–500 mg twice daily34,35.

Topical antibiotics are almost as effective as systemic antibiotics, but they may lead to the selection of resistant bacteria on the skin surface and to contact-allergic eczema. However, as there is negligible systemic absorption, this approach is safe in pregnancy. Examples include topical erythromycin (Stiemycin, Eryacne, Benzamycin, and Zineryt, which contains zinc in addition to erythromycin to reduce bacterial resistance and increase efficacy) and tetracycline (Topicycline, which is no longer available in the United States). The use of topical clindamycin during pregnancy has been associated with pseudomembranous colitis36 and, in order to reduce systemic absorption, topical clindamycin phosphate is preferable to the hydrochloride salt. These topical preparations should be applied once or twice daily to the face and/or upper trunk.

Systemic drugs

Although isotretinoin is rapidly cleared and is not stored in tissue, pregnancy should be avoided until 2 months after the drug has been discontinued. However, etretinate and its metabolite acitretin (Neotigason) are a potential hazard for 2 years after therapy has been stopped because of their very slow elimination from the body.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic cutaneous disease caused by the occlusion and rupture of follicular units, in which the resulting inflammatory response may secondarily involve the apocrine glands. Recurrent lesions develop in the axillae (Figure 10.7), groin, and perineal areas, with the formation of abscesses and with draining sinuses and progressive scarring.

In extreme cases, the entire vulva may be affected over many years, resulting in gross scarring and deformity, often associated with substantial psychosexual problems. The condition may remit during pregnancy as a result of reduced apocrine gland activity37 but a recent review showed no consistent relationship between hidradenitis suppurativa and pregnancy in 38 women38.

Management

Management often involves the use of long-term systemic antibiotics, such as erythromycin or tetracycline. However, tetracycline should be stopped before a planned pregnancy. If antibiotics are unsuccessful, alternatives include oral acitretin (which must also not be used in pregnancy) or surgery, where all the apocrine glands in the affected areas are excised. The carbon dioxide laser has been used to treat this condition, with considerable success39. Although repeated treatments may be necessary, the clearance rate and cosmetic results are excellent.

Erythema nodosum

Erythema nodosum is a reactive inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, which is secondary to a wide variety of underlying conditions (Table 10.4). It can also occur de novo in pregnancy40. It presents with the sudden onset of ill-defined, tender, erythematous nodules or plaques, distributed symmetrically over the anterior legs (Figure 10.8). Lesions may also develop over the calves, arms, trunk, and face. Fever, malaise, and arthralgias may precede or accompany the eruption. Lesions usually resolve in 6–8 weeks.

Table 10.4 Underlying Conditions of Erythema Nodosum

| Infections |

| Streptococcus spp. |

| Tuberculosis |

| Leprosy |

| Coccidiomycosis |

| Drug Allergies |

| Sulfonamides |

| Oral contraceptives |

| Other Disorders |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome |

Management

Treatment is supportive and includes bed-rest and mild analgesics such as paracetamol. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should not be used in pregnancy, especially in the third trimester. This is because they may constrict the ductus arteriosus in utero, or inhibit or prolong labor by inhibiting prostaglandin synthetase. Systemic corticosteroids, if not contraindicated by an underlying infectious disease, are necessary in some cases. Treatment of the underlying disease or removal of the inciting drugs is essential. Erythema nodosum may be a presenting feature of coccidiomycosis in pregnancy and can be associated with an improved disease outcome41,42. Three cases of erythema nodosum have recently been described in association with the antiphospholipid syndrome43.