CHAPTER 27 Disorders of the Achilles Tendon

INSERTIONAL ACHILLES TENDINOPATHY

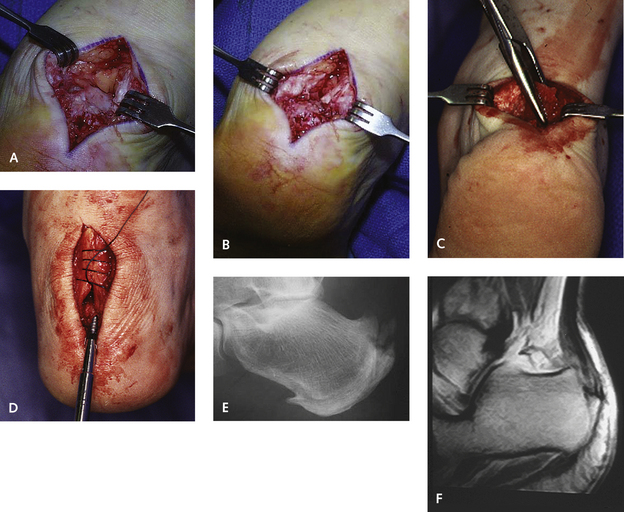

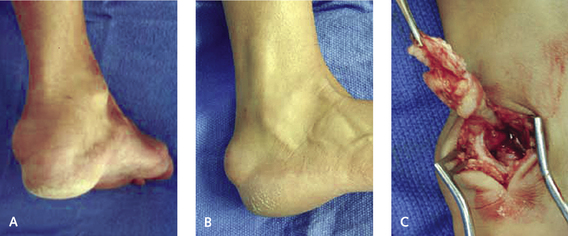

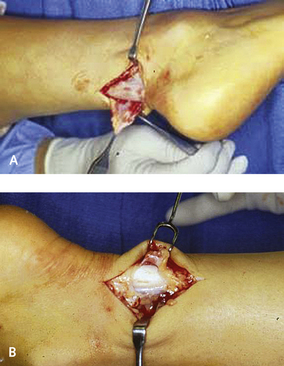

Once nonoperative methods for treatment of insertional Achilles tendon disease have failed, the next decision to be made is the type of incision used for the surgical approach. I make this decision according to the extent of the underlying disease, the presence of tendon degeneration, and the location of maximum tenderness. If osteophytes are present on the posterior central aspect of the heel, then I use a central splitting incision of the posterior Achilles tendon and calcaneus. This incision works well, and the entire broad plate of the osteophyte can be removed. Use of this Achilles splitting incision is advantageous because it allows direct visualization of the disease and ease of dissection of the torn portion of the tendon with removal of the osteophyte. This invasion is associated with a more prolonged recovery, however (Figure 27-1).

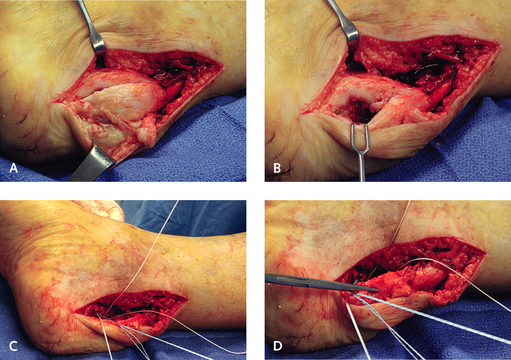

If the pain is not posterocentral, the incision should be made medially or laterally, because the irritated or torn portion of the tendon may not be visible from the central or posterior splitting incision. If no large osteophyte is present in the posterior calcaneus and thickening and degeneration of the tendon are diffuse, then a medial or lateral incision is made to debride the retrocalcaneal space, thereby decreasing the impingement of the calcaneus against the Achilles tendon (Figure 27-2).

The operation is performed with use of local anesthesia and the patient in a prone position. A 4-cm vertical incision is made directly over the tendon extending toward the junction of the plantar heel skin. The incision is deepened through the tendon, which is split longitudinally, and the incision is deepened directly onto bone, even inferiorly. The central portion of the tendon is the location of maximum degeneration, and this area can be exposed either through a vertical ellipse or by spliting the tendon and separating it with a retractor. The enlarged osteophyte is visible below the central portion of the degenerated tendon, and this is excised with an osteotome. The dorsal posterior surface of the calcaneus must be smoothed down to remove any potential source of irritation on the anterior aspect of the Achilles tendon insertion. The tendon must be repaired with a running locking suture. If significant degeneration and tearing of the tendon that could lead to its separation off the calcaneus are noted, a suture anchor can be used to help with the reattachment of the tendon. Usually, however, placement of an anchor is not necessary, because wide bands of the tendon, inserted both medially and laterally, prevent rupture. Removal of up to one third of the central aspect of the tendon does not disrupt its attachment whatsoever, and possibly up to half of the tendon insertion can be detached (Figure 27-3).

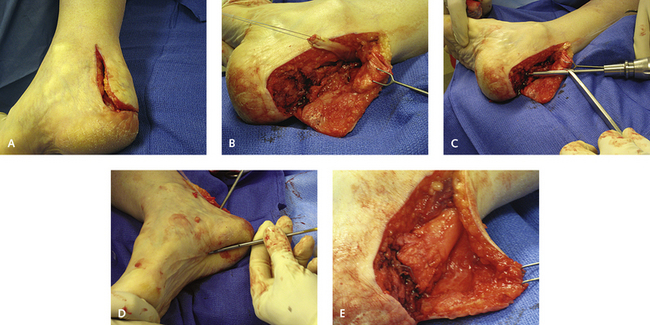

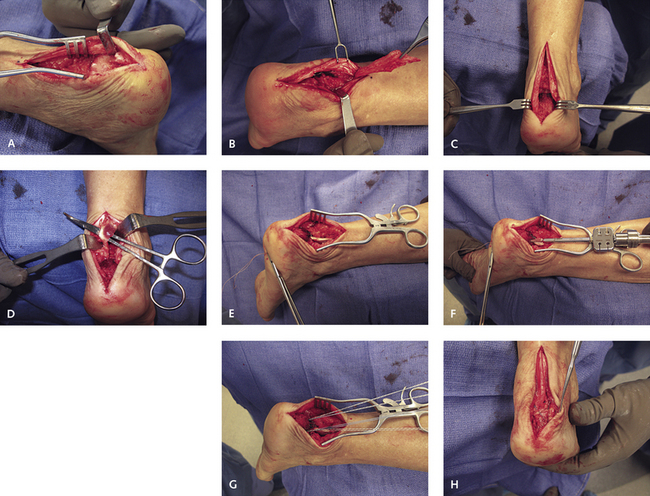

Figure 27-3 A and B, This degenerative insertional tendinopathy extended much farther proximally than that seen in Figure 27-2, and after debridement, little healthy tendon remained. C, The impinging bone was resected. D, The flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon was harvested directly deep to the incision. E, The tendon was passed into a 4.5-mm tunnel in the calcaneus. F-H, The FHL tendon was secured with an interference screw, and then a double row of suture anchors was used to secure the Achilles tendon with a criss-cross locking suture over the tendon.

Careful attention to postoperative care is essential during healing of central splitting and other incisions that are used to expose the distal Achilles tendon. Healing invariably occurs uneventfully provided that the foot is held immobilized to prevent formation of a hypertrophic scar, which could be catastrophic. Formation of scar directly over the heel will lead to problems with shoe wear. The foot must therefore be immobilized postoperatively until full wound healing has occurred. Rehabilitation of the Achilles tendon is important, requiring strengthening modalities, heel elevation, and orthotic arch support. Generally, I recommend use of a removable range-of-motion walker boot for approximately 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, allowing plantar flexion but blocking dorsiflexion, to facilitate physical therapy and treatment.

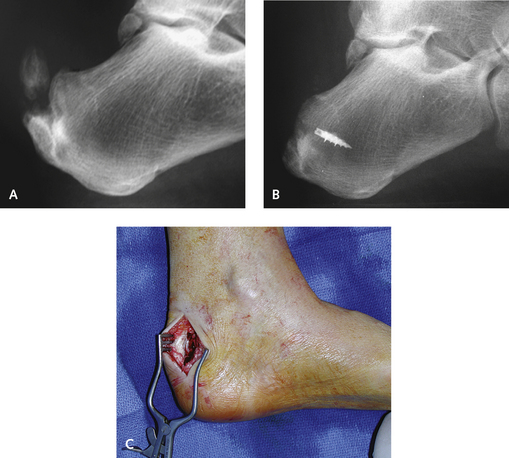

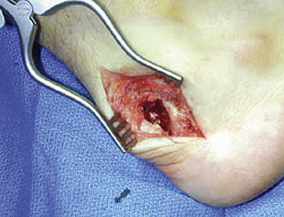

Insertional tendinopathy should be distinguished from Haglund,s syndrome and retrocalcaneal bursitis. In patients with these latter conditions, the bursitis occurs as a result of enlargement of the dorsal superior lateral aspect of the calcaneus. The dorsolateral tuberosity causes impingement against the lateral insertion of the Achilles tendon, and retrocalcaneal bursitis develops. If the bursitis is refractory to nonoperative treatment, the best approach is through a short dorsolateral incision just anterior to the Achilles tendon (Figure 27-4). The incision is deepened through subcutaneous tissue, the retrocalcaneal bursa is excised, and the insertion of the Achilles tendon and the enlarged posterolateral bone are exposed. Only a lateral ostectomy is performed; a more medial extension of the ostectomy is unnecessary. In the event that bilateral bone prominence is present, I prefer to use a more extensile J-incision. Strictly speaking, the latter condition is not true Haglund’s syndrome, but this anatomic variant does occur (Figure 27-5).

Alternative incisions may be used to correct insertional tendinopathy, including an extended J-incision. The advantage of this type of incision is that it gives complete access to the entire insertion of the tendon. I use this incision for more severe diffuse insertional tendinopathy when I do not think that I can access the entire tendon through either a central splitting incision or bilateral incisions. With use of the extended J-incision, the tendon is completely detached from its insertion, the offending bone is debrided, the retrocalcaneal space is denuded, and then the tendon is reattached with a suture anchor (see Figure 27-5).

In addition to the debridement of the insertion of the tendon with bursectomy and ostectomy, the Achilles tendon needs to be repaired for management of severe insertional tendinopathy with loss of the integrity and function of the tendon (Figure 27-6). Generally, the tissue is insufficient in amount or of such poor quality that a simple debridement cannot be performed. The management of these more severe forms, as discussed later in the section on management of noninsertional tendinopathy, consists of resection of the insertion of the Achilles tendon with either a flexor hallucis longus (FHL) transfer or an Achilles tendon allograft (Figure 27-7). These more extensive procedures are distinguished from the simple superolateral exostectomy (Figure 27-8). The use of the FHL as a tendon graft for insertional tendinopathy is not as common as for more extensive noninsertional tendon disease, but certain circumstances will necessitate use of either the FHL tendon, a tendon graft, or a V–Y advancement (Figure 27-9). The choice will depend on the extent of the disease, the ability to use the remainder of the distal Achilles, and the activity or athletic needs of the patient.

MANAGEMENT OF PARATENDINITIS

Recognized as a separate disorder from the degenerative tendinopathies, paratendinitis is an inflammatory condition, typically occurring in athletes, and usually associated with hyperpronation of the foot in conjunction with a mild gastrocnemius muscle contracture. The usual nonsurgical methods of treatment, including contrast bathing, physical therapy, orthotic arch support, and gastrocnemius muscle stretching, usually are sufficient to alleviate symptoms. If the paratendinitis is persistent, a brisement of the paratenon is performed, beginning with injection of 3 mL of lidocaine. The No. 20 needle is inserted just underneath the paratenon, advanced into the tendon, and then backed off so that it lies indirectly under the paratenon. Injection of the anesthetic not only confirms the diagnosis and the correct location of the needle but also elevates the inflamed, scarred paratenon off the tendon. This technique works well enough that it should be tried before surgery.

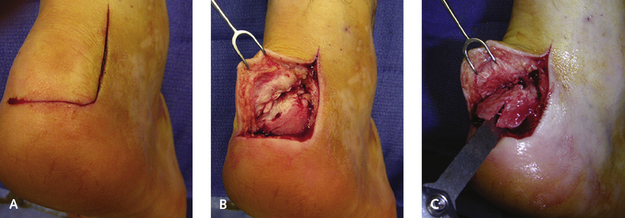

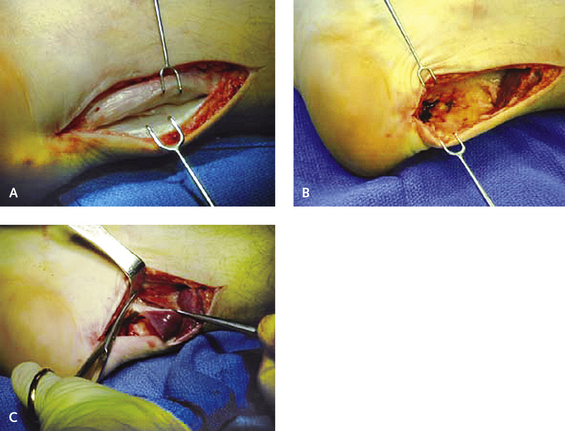

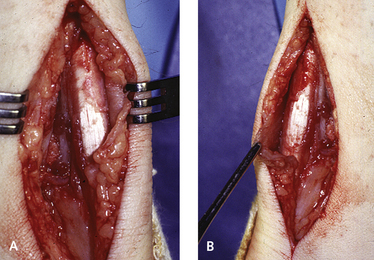

The surgical procedure for paratendinitis involves a short incision on the medial aspect of the tendon over a length of 2 cm (Figure 27-10). The subcutaneous tissue is elevated, and then the paratenon is identified and incised. The paratenon is then elevated off the Achilles tendon and stripped by excising the superficial anterior sheath of the paratenon medially, dorsally, and laterally as one sleeve (Figure 27-11). The deep ventral surface of the Achilles tendon is left intact, to leave the blood supply undisturbed. The foot should be immobilized for a short period to prevent any hypertrophic scar formation, and then therapy with cross-training and modalities used in rehabilitation after boot immobilization can proceed for approximately 3 weeks.

Figure 27-10 A and B, The typical appearance of the inflamed paratenon, which was subsequently removed.