(1)

Department of Dermatology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Abstract

Tinea pedis, “fungus of the foot,” involves marked toeweb scaling, a “moccasin” pattern of scaling on the soles, and maceration. Dermatophytes including Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum are responsible. T. rubrum is ubiquitous, especially in locker rooms and showers (causing “athlete’s foot”). The same phenomenon is occurring in tinea pedis as in eczema. The difference is that in tinea pedis the fungus disrupts the stratum corneum and plays the role that genetic abnormalities play in eczema. Axillary granular parakeratosis, a rare disease with an unknown cause, presents clinically with a pruritic, hyperpigmented or dull red hyperkeratotic plaque in the axilla. In our examination of multiple sections of a specimen from axillary granular parakeratosis, we found periodic acid–Schiff positive occluded sweat ducts in the upper epidermis and proximal stratum corneum. We believe the occlusions arise from staphylococcal biofilms similar to those seen in miliaria, and the granules play the role of genetic abnormalities in eczema. In seborrheic dermatitis, biofilm-producing staphylococci and occluded sweat ducts form the environmental “hit” of the double-hit phenomenon and yeasts play the role of the genetic abnormalities in eczema. Management of seborrheic dermatitis usually involves bland shampoo and infrequent use of soap. The response is similar to eczema because it truly is eczema. “Cradle cap” is similar.

Keywords

Axillary granular parakeratosisCradle capDouble-hit phenomenonEczemaMoccasin distributionOccluded sweat ductsSeborrheic dermatitis Staphylococcus Tinea pedisToeweb“One hand, two feet”The presentations for tinea pedis are represented in part by the following terms: moccasin, toeweb, and “one hand, two feet” (Figs. 9.1, 9.2, and 9.3). Tinea is Latin for fungus moth, a moth that lives on and eats fungi and molds. In its dermatological derivation, the “moth” strangely has been deleted, and the “fungus” has assumed importance. Hence, tinea pedis describes “fungus of the foot,” a pruritic rash from which fungi can be routinely cultured and/or visualized on potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination.

Fig. 9.1

Tinea pedis. Pink erythema and marked scaling are present along the sides of the foot (where a moccasin would fit)

Fig. 9.2

Tinea pedis. Marked toeweb scaling and maceration are present in the fourth and fifth toeweb space. Onychomycosis is also present

Fig. 9.3

Tinea pedis. This patient’s bilateral soles show scaling. This is ordinarily accompanied by a moccasin-type distribution and toeweb involvement. One hand is often involved, giving the “one hand, two feet” presentation

The fungi that are involved are dermatophytes, asexual species that have identifiable cultures [1]. Three variants are most commonly associated with tinea pedis: Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum. In this discussion, we will be considering mostly acute and chronic tinea pedis, and the organism most associated with these presentations is T. rubrum. This fungus is ubiquitous, but it has commonly been found in locker rooms, showers, and other sites where transmission to fungal-naïve individuals can occur. This is the reason it is often referred to as “athlete’s foot.”

Acute tinea pedis is very pruritic, such that in one advertisement for an antifungal product, the spokesman says, “If you have athlete’s foot, you are always sneaking a scratch.” Often the pruritus is relieved only when a painful fissure between the fourth and fifth toes (the most common location) is created. Pain is more tolerable to the patient than the incessant itch. The itch associated with vesicular or bullous tinea pedis is similar and is relieved when the intense scratching creates a painful erosion.

Chronic tinea pedis is characterized by scaling both interdigitally and in a “moccasin” pattern on the soles and sides of the feet [1] (Fig. 9.4). It is also associated with T. rubrum predominantly, though not exclusively. The chronic form involves very little pruritus and itches primarily when it transforms locally into the acute vesicular variant. “Locally” refers to an interdigital space or the instep (Fig. 9.5); rarely does it refer to the lateral feet. This transformation occurs with sweating or with feet being occluded in wet footwear.

Fig. 9.4

Chronic tinea pedis. Marked redness and scaling is present on the entire sole. This was culture positive for Trichophyton rubrum

Fig. 9.5

Chronic tinea pedis. Erythema and mild scaling are present in the moccasin distribution. Many red papules and papulovesicles are present proximally; one crusted papulovesicle is also present

With routine topical treatment of acute tinea pedis with an “azole” antifungal, the patient gets relief from the itch in 2–3 days. On occasion, the itch will intensify in the first few hours after application of the topical. Various topical agents have been advocated for the treatment of tinea pedis, including topical azoles, tolnaftate, ciclopirox, terbinafine, and undecylenic acid. None of these has met with total success at “curing” either form of the disease [2]. Treatment may clear the rash transiently (Fig. 9.6), but the eruption will frequently recur. The same may be said of oral medications, including griseofulvin in all its formulations, terbinafine, and the oral azoles. These may also not only clear the eruption, but also give mycological cure in 35 % [3]. The “clear” state is not permanent, however, and the eruption frequently reappears.

Fig. 9.6

Transiently resolving tinea pedis. The bilateral soles have only mild erythema remaining; no scale is present. KOH and cultures are negative

The reason the fungus returns and the rash recurs on the glabrous skin even after the treatment onslaught as above, after successful treatment of associated onychomycosis, is that patients have no demonstrable delayed-type hypersensitivity to this fungal organism. Skin tests for Trichophyton will be positive at 12–24 h but are negative at 48 h and beyond. This indicates accelerated immunity versus Trichophyton, but no delayed-type immunity [4, 5]. The delayed form of hypersensitivity obviously is the important type of response necessary in killing this organism. This immune state represents a selective defect of delayed sensitivity (HIV infection, conversely, represents a total lack of delayed sensitivity because the T lymphocytes that mediate the delayed type of hypersensitivity are destroyed by that virus).

With all that as foregoing, it was noted that ceramide-containing cream applied to the feet in patients with chronic tinea pedis cleared the scaling totally (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8).

Fig. 9.7

Scaling is present on the entire sole. This scale was KOH positive for fungal hyphae and culture positive for Trichophyton rubrum

Fig. 9.8

The sole is clear after application of ceramide-containing cream only. No topical antifungals were used. KOH and cultures were negative

This response was noted in patients who had had tinea pedis for more than 50 years; nothing had cleared it totally. The tinea pedis was documented with positive fungal cultures and positive KOH scrapings. Skin tests revealed negative reactions to Trichophyton at 48 h but positive reactions at 24 h. The patients did not have anergy because other sensitizers elicited positive reactions to nickel, neomycin, and others.

The ceramide-containing cream completely healed the dry, scaling, fissured heels (for which it was originally applied) [6], and it also cleared the tinea pedis, yielding negative KOH preparations and cultures. All these samples were taken from nonscaling areas. If any scale happened to persist, the cultures from those sites were positive.

Admittedly, anecdotal evidence such as the foregoing is unreliable; but, with the approval of our institutional review board, we evaluated this phenomenon further. Twenty-seven of 30 patients who used ceramide-containing cream had skin clearing similar to the anecdotal story. In the scaling areas (premoisturizer) the cultures were positive for T. rubrum, and after 2 months of once-daily application, the feet were clear and both culture and KOH tests were negative. The majority of these patients had onychomycosis that did not clear with the cream. Of even greater interest, if this cream is applied to an acute eruption, the symptoms abate in 8–12 h as opposed to 36–72 h with the best topical antifungals. One further protocol revealed that the ceramide-containing cream had no antifungal properties. Cultures of T. rubrum grew right up to the cream without any zone of inhibition (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.9

On this antibiotic-containing fungal culture medium, there is a white colony with a red back (typical for T. rubrum). No zone of inhibition is present around the ceramide-containing cream, allowing the fungal colony to grow to the edge of the cream

All of our patients who were sampled had positive cultures for staphylococci capable of making biofilms and lesional scrapings that showed biofilms on Gram stains. All were culture positive for T. rubrum. XTT assays showed that these staphylococci were biofilm producing and multidrug resistant. Two patients had biopsies done to confirm the diagnosis of tinea pedis and to rule out dyshidrotic eczema. These showed PAS-positive occlusion of the acrosyringia (Figs. 9.10 and 9.11), and they also had Toll-like receptor 2’s at the sites of the ductal obstruction rather than in the basal area as seen in control skin (Fig. 4.3).

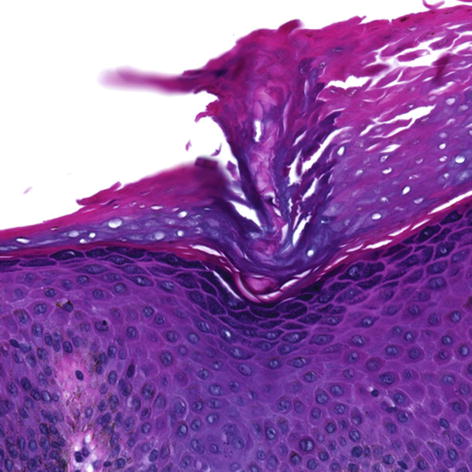

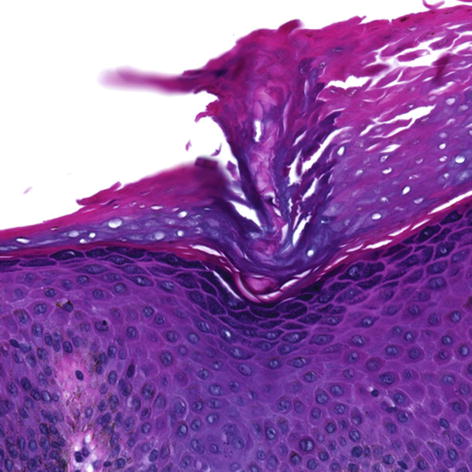

Fig. 9.10

The duct in the lower and middermis is patent; in the proximal stratum corneum, there is a ductal occlusion and the exit is completely occluded. Inflammatory and parakeratotic cells are noted in and around this occlusion (40×)

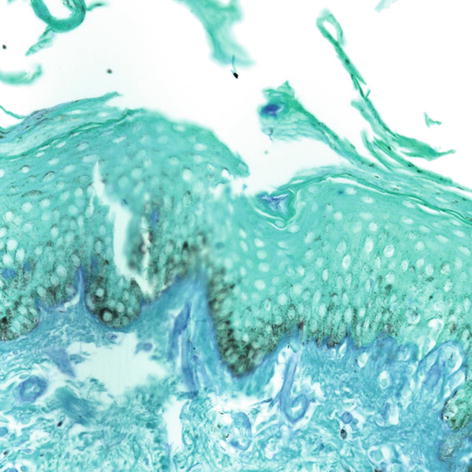

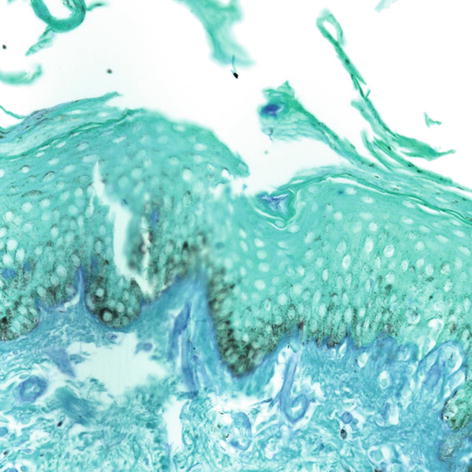

Fig. 9.11

A periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) positive occlusion is noted in the duct in the distal stratum corneum. A faint PAS staining is present in the duct in the granular layer (40×)

This indicates that the very same phenomenon is occurring in tinea pedis as in eczema. The difference between them is the dermatophyte, which disrupts the stratum corneum in the fungal presentation. In eczema, the genetic abnormalities play this role.

The response in acute tinea pedis to the application of ceramide-containing cream is very similar to that described by O’Brien [7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree